Some years ago I wrote on ARM Netzahualcoyotl, the last WWII Gearing class in service worldwide. Mexico also was the very last user of the WWII Fletcher class, however unlike Mexico’s FRAM-modernized Gearing, in 2001 ARM Cuitláhuac remained “frozen in time” to a WWII technology level.

(USS John Rodgers (DD-574) during WWII.)

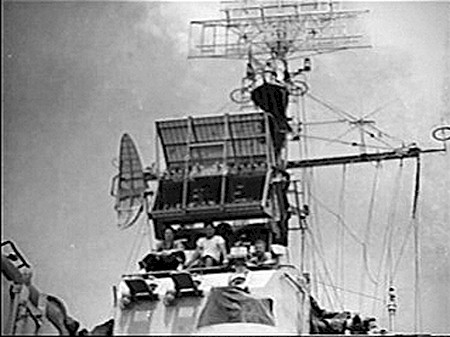

(ARM Cuitláhuac, the former USS John Rodgers, in 2000. It was the last Fletcher still in service anywhere in the world.)

the Fletcher class

These were the US Navy’s workhorse of WWII. When the design was finalized in 1939 it was the largest and best-equipped destroyer in the US Navy’s history. Eleven different shipyards built them during WWII including four which had never built destroyers of any type before. The cost was $6 million ($137 million in 2024 dollars) so they were not exorbitantly expensive either.

This is the most numerous destroyer class in US Navy history, with 173 being completed before production ended in February 1945. During WWII 19 of the 173 were sunk, all in the Pacific, plus another 6 heavily damaged which were not worth repairing once Japan surrendered. More than half the losses during all of WWII came in the final five months at the height of the kamikaze threat.

The Fletcher class displaced 2,500t and measured 376’6″ x 39’6″ x 17’6″. Propulsion was four boilers, two geared steam turbines, two shafts for a top speed of 36½ kts (some hit 38 kts+ during their sea trials). The complement was 9 officers and 263 enlisted sailors.

The main gun armament was the Mk12 5″ gun, the finest weapon of its type of any nation during WWII and one of the best era-adjusted naval weapons of all time. These were in five Mk30 single turrets. The 5″ guns were dual-purpose, AA and surface battle. Further AA guns on a Fletcher were of 40mm and 20mm in varying loadouts during WWII.

(USS John Rodgers during WWII.)

The Fletcher class was designed with anti-submarine warfare (ASW) in mind and by 1939 standards had an impressive ASW loadout: two traditional astern drop racks and half a dozen Mk6 K-Guns.

Above is USS John Rodgers‘s stern during 1943 showing a typical early-WWII layout: Mk3 depth charge racks with five-round reloaders. The depth charges are the Mk7 “ashcans” which was a common early-WWII type. The quad cylinders are unrelated Mk4 smokescreen generators.

Above is USS John Rodgers near the end of WWII. The Mk3 racks now carry eleven Mk9 depth charges. This “teardrop” design sank faster (22fps) than the older “ashcan” shape and had a deeper maximum depth. The Mk9 was also compatible with the K-Guns described below.

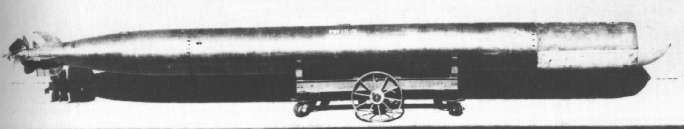

(Mk9 depth charge.) (photo via navweaps website)

A follow-on, the Mk14, had a proximity fuze developed by RCA but started production too late in 1945 to see combat. For all intents and purposes, the Mk9 was the US Navy’s final stern-drop depth charge and the only model retained in quantity after WWII.

Stern-drop depth charges were not as an effective of a WWII tactic as sometimes thought. The destroyer had to first detect a submarine on sonar. Due to the “baffles” (noise of its own propellers) the detection cone was only 180°

The destroyer then had to maneuver onto a parallel course, “running over” the submarine’s position from behind. If the run failed, the destroyer had to accelerate and circle back around, regain sonar contact, and start a new attack run. After WWII the Royal Navy estimated that if used alone, this tactic failed 94% of the time.

An alternative was the Mk6 K-Gun.

These sat on the deck edges, facing sideways. A Mk6 mount was the actual K-Gun and a three-round reload cage. This was a “bolt-on weapon” requiring no deck penetrations and no electricity.

(USS John Rodgers during WWII.)

A depth charge was chained into a disposable arbor, which was then loaded into the K-Gun. A pyrotechnic charge in the sideways breech launched the arbor and the depth charge chained to it.

The range was still very short: 60 yds, 90 yds, or 150 yds. However attacks could be nearly-immediate: once a submarine was detected, the destroyer turned 90° and fired; there was no complex maneuvering involved.

Finally a Fletcher class destroyer carried unguided ship-to-ship torpedoes, fired from two quintuple tube banks; or in official US Navy terminology “A.W. (abovewater) Pentad Mounts”.

(The blast hut of a Mk15 tube bank on a Fletcher class destroyer during WWII, in front of the third 5″ gun turret. The Mk14 tube bank was identical but lacked the hut, which was simply to shield the two crewmen from nearby gun concussions. On the Fletcher class, a Mk14 was the forward bank and a Mk15 the aft.)

(The Mk14/Mk15 spoon extensions were often folded upwards when not in battle to limit the chance of them accidentally being bent by shipboard work. The firing mechanism used 38 ounces of sodium nitrate (which sailors called “blackpowder”) to generate gasses sufficient to eject the torpedo, which rode on bronze rollers inside the barrel section.)

The straight-running 21″ Mk15 was the US Navy’s destroyer torpedo during all of WWII from start to finish. It was powered by H²O² concentrate fuel and had a 825 lbs warhead of HBX explosive. It weighed just under 2 tons. There were three range / speed settings: 6,000 yds at 45 kts, 5 NM at 33½ kts, and 7¼ NM at 26½ kts. At the latter’s extreme it would take 16 minutes to intersect the target, which would have had needed to maintained its speed and course, illustrating the difficulty of long torpedo shots.

(Mk15 torpedo during WWII. Somewhat confusingly the weapon shared the same nomenclature as the tubes.)

Production halted in 1944 as there were already 9,700 made; the vast majority still being unfired. A planned successor was the Mk17 of which only 450 were made late in WWII with none being used and the rest of the order being cancelled. The Mk15 would be the last American ship-to-ship torpedo.

This genre of war at sea was fading away by 1945. Advancements in radar and gunnery made getting close for a high-speed setting, straight-run torpedo shot dangerous. The tube banks added 18½ tons each above the ship’s center-of-gravity. They also took up “prime real estate” on deck, and during WWII some destroyers with two banks had one replaced by more AA guns to fight the kamikaze threat.

No post-WWII American destroyer was designed for unguided ship-to-ship torpedoes.

USS John Rodgers (DD-574) during WWII

USS John Rodgers, the future ARM Cuitláhuac, was built by Consolidated in Orange, TX. The keel was laid on 25 June 1941. The ship was launched on 7 May 1942 and commissioned on 9 February 1943. The name honored four different John Rodgers of four generations, serving at sea from the War of 1812 to World War One.

(USS John Rodgers as completed in 1942.) (photo via navsource website)

USS John Rodgers was the final Fletcher built by Consolidated with a round bridge and one twin 40mm aft. Later ships had an enlarged, squared-off bridge and three 20mm guns aft.

(USS John Rodgers in 1945, near the end of WWII.)

The above photo was later during WWII. An SC-4 air search radar is now atop the mainmast. The Mk37 GFCS on the bridge now has Mk12 and Mk22 gunnery radars. Aft is a new pole with the electronic warfare kit described later.

The above photo of USS John Rodgers was taken aboard USS Hornet (CV-12) on 14 May 1945. A Japanese Ki-61 “Tony” fighter, almost certainly a kamikaze, was descending straight towards USS Bennington (CV-20). As it passed over USS John Rodgers, 20mm gunfire from the destroyer likely impacted a bomb on the Ki-61 as the entire plane totally exploded mid-air, so close that pieces of it were found on the destroyer’s deck.

(USS John Rodgers headed back to the USA a month after WWII’s end.) (photo via navsource website)

USS John Rodgers, like many Fletchers, was still in good condition but now surplus to the US Navy’s peacetime needs. It decommissioned on 25 May 1946 and was put into mothballs, where the ship would remain for two and a half decades. As such it was “frozen in time” to a WWII technology level.

Fletcher class fades from use

While USS John Rodgers went into mothballs along with other Fletcher class destroyers, others remained in commission and were upgraded with Cold War-era weapons and electronics.

(The class leadship USS Fletcher (DD-445) survived WWII and served on afterwards.)

This 1969 photo of USS Fletcher was taken shortly before it decommissioned. It shows a Mk25 replacing the WWII radars on the Mk37 GFCS, AN/WLR-1 radomes further aft, and a RUR-4 Weapon Alfa replacing the upper forward 5″ gun. Weapon Alfa used a Mk108 “rocket mortar” to shoot 525 lbs ASW rounds out to ½ NM. It was not really a success and was soon eclipsed by ASW homing torpedoes, ASW missiles, and helicopters.

The last Fletcher class destroyer in the US Navy was USS Uhlmann (DD-687).

USS Uhlmann differed significantly from its WWII appearance having a new tripod mast for new radars, AN/WLR-1, AN/SPG-35, Mk33 secondary guns, and ASW homing torpedoes replacing the WWII ship-to-ship torpedoes. It decommissioned on 15 July 1972.

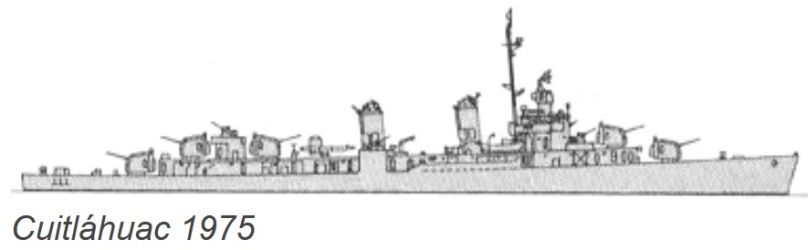

Worldwide other than Mexico, the last Fletcher still in service was ROCS Kun Yang of the Taiwanese navy. It had been USS Yarnall (DD-541) during WWII.

ROCS Kun Yang was even further removed from the WWII layout, having an automated Italian 76mm gun, RIM-74 Sea Chaparral surface-to-air missiles, and Israeli digital electronics. ROCS Kun Yang decommissioned on 16 October 1999.

ARM Cuitláhuac

During 1970 Mexico purchased the ex-USS John Rodgers along with a sister-ship, the ex-USS Harrison (DD-573). Both had been in mothballs since 1946 and were still in WWII configuration. They were members of a rapidly-shrinking club: WWII destroyers still extant in the reserve fleets but having never been upgraded in the then-25 years since the war.

(The sister-ship became ARM Cuauhtémoc and confusingly, wore a pennant number later used by ARM Cuitláhuac.)

The ex-USS John Rodgers was renamed ARM Cuitláhuac. The name honored the second-to-last Aztec emperor.

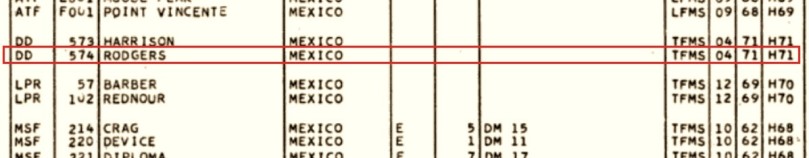

The 1970 price for ARM Cuitláhuac was $150,000 ($1.2 million in 2024 money) which was a tiny fraction of its WWII cost and little more than its scrap metal value. ARM Cuitláhuac was a Section 21 sale, via the Foreign Military Sales program. Eligibility for FMS Section 21 was a WWII warship already decommissioned and stricken off the Naval Vessels Register. The long-decommissioned ex-USS John Rodgers had finally been stricken off the NVR in 1968 and was in the Maritime Administration’s “disposal” category in 1970.

(The former USS Harrison (left) and USS John Rodgers in mothballs.)

The 19 August 1970 sale was “as-is, where-is” meaning the recipient was responsible for taking delivery at their expense, in ARM Cuitláhuac‘s case from Charleston, SC. The USA guaranteed that the ship would be in no better, no worse condition than the pre-sale inspection. Any further alterations or upgrades were entirely at the recipient’s expense. Both Fletchers bought by Mexico had only the aft quintuple tube banks still aboard in 1970 and none of the WWII 20mm guns. They still had all the 5″ and 40mm guns and ASW weapons.

(The above is from a July 1971 snippet of an International Logistics Program census of exported American warships. “TFMS” means ARM Cuitláhuac had been permanently transferred, via Foreign Military Sales. “04 71” was April 1971 when the 1970 deal was considered concluded, “H71” means an American had physically verified the warship in active Mexican use, the most recent time being in 1971.)

ARM Cuitláhuac was assigned to Mexico’s Pacific fleet.

EEZs and the Mexican navy

Maritime law is not the most thrilling topic but it is highly relevant to why Mexico bought ARM Cuitláhuac in 1970, why it never upgraded it over the next three decades, and what it was doing in that timeframe.

Before WWII there was no agreement as to how sea frontiers (national borders in the ocean) were set. Even afterwards the concept was shaky. For example after the Korean War, of 92 sovereign nations 34 used a 12 NM line, 9 claimed more, and 49 claimed less – some still 6,000 yards, the old “cannonball’s longest fall” limit from the days of wood & sail. The 12 NM line eventually became the worldwide norm. These are undisputed sovereign waters, including their airspace, where the nation’s laws fully apply.

An Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is totally different and the concept did not even exist at all before WWII.

The EEZ concept started just 26 days after WWII ended aboard USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. President Truman issued Executive Orders #2667 and #2668, stating that the USA would exercise economic rights to “…fisheries in certain areas of the high seas” and in the “…subsoil and sea-bed of the continental shelf” beyond its 12 NM limit. The proclamations were vague. Within the next two years other nations (Peru and Chile were the first) started issuing their own proclamations, many of which really were not in harmony.

(At 00:00 on 1 January 1946 the US Coast Guard transferred from US Navy emergency control back to the Treasury Department. It was tasked with enforcing the President’s proclamations, with leftover WWII assets like these PBY-5A Catalinas.)

Over many years and many diplomatic squabbles the EEZ generally became defined as 200 NM from the nation’s shoreline, extended by any offshore islands. When two or more nations are closer than 200 NM from each other, they split the difference.

An EEZ is not a sovereign national claim. They remain international waters. It covers the ocean down to the seafloor (and inside the seafloor) but not the airspace above. The nation’s laws do not apply. It is totally irrelevant to military warships, civilian passenger liners, and civilian freighters. Vessels of any type, including trawlers, have free passage through, as long as they do not undertake a proscribed activity – fishing (including crustaceans and pearls), oil, or underwater mining.

These activities greatly increased in scope and economic importance. Before 1939 fishing was a low-key affair. By 1949 wartime inventions like electronic navigation and improved radios, along with the many nautical charts made during WWII, allowed trawlers to know exactly where they were and where they wanted to go, with fishing fleets now operating very far from their home waters.

A totally new resource of the sea emerged after WWII. During the war, Great Britain built Maunsell Forts in the Thames Estuary and English Channel. These allowed detection of Luftwaffe air raids before they entered British airspace.

The USA’s petrochemical industry saw the promise in structures like this once peace came. Less than two years after WWII’s end, there were Maunsell-type oil platforms off the Louisiana shoreline, in some cases as far as 18 NM into the Gulf of Mexico. Nine years after WWII, there were already “jackups” (primitive deepwater rigs) even further out into international waters of the Gulf.

As all this was happening, WWII advancements like radar and long-range maritime warplanes made it easier for second-tier navies to monitor much bigger portions of sea than was practical for them before the war.

(The Mexican navy operated surplused PBY Catalinas after WWII.)

patrolling Mexico’s EEZ

Mexico has a huge EEZ, the 13th largest on Earth.

Peacetime monitoring of an EEZ does not require high-end warships. They do not need to be fast. They do not need AA or ASW weapons, armor, jammers, missiles, or the such.

What they do need, above all, is to be cheap. They need to be reliable and have a token weapons fit. That is pretty much it.

Mexico has a unique military situation: the neighbor to the north is a nuclear superpower and infinitely stronger. Meanwhile Mexico’s neighbors to the south are themselves much weaker than Mexico. Mexico faces no real external military threat.

The Mexican navy after WWII reflected this in size and technology. As the lack of any conventional threat became obvious, attention to economic control of the seas increased. During 1958 and 1959 incursions of Mexican fishing trawlers into Guatemalan waters were met by a military response and nearly caused a war. Mexico had a war plan drawn up and the Guatemalans dynamited several of their own bridges along the expected invasion path.

(A Mexican fishing trawler being strafed by a Guatemalan P-51 Mustang during December 1958. Two trawlers were sunk. Diplomacy the following year calmed the situation just as the two nations appeared headed for war.)

During October 1962 Mexico made a huge buy out of the American mothball anchorage at Orange, TX, centered on twenty Admirable class minesweepers.

(ARM Cadete Francisco Marquez had been USS Diploma (MSF-221) during WWII. It served the Mexican navy until 2000.) (photo by Carlos Pizano)

These WWII minesweepers were intended for use as EEZ patrol ships. They cost little to buy out of American mothballs and were uncomplicated and cheap to operate.

The 1970 availability of the two Fletcher class ships was an opportunity too good to pass up. Whatever their limitations in unmodernized WWII form, there might never be another opportunity to buy destroyers for $150,000 each. Experiences with the Admirables had illustrated the usefulness of low-technology types for the EEZ mission, meanwhile the two Fletchers remained at least plausible conventional-combat assets.

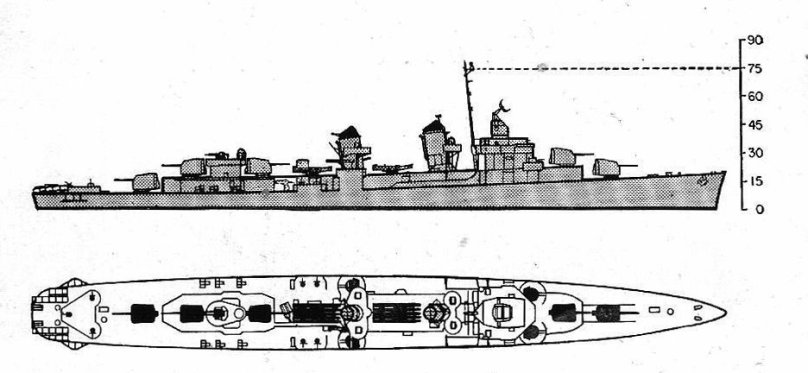

(line drawing via navypedia website)

in Mexican service

When the two Fletcher class ships entered Mexican service in 1970 they were that nation’s biggest warships ever up to that time.

ARM Cuitláhuac was assigned to the Pacific where offshore oil was less of an issue than the Gulf fleet. However this region’s EEZ had a more pronounced problem with fishing poachers. During the 1970s there were organized “gangs” of trawlers from the United States which would fish inside Mexico’s EEZ and then return to California to process their catch. As this problem was subsiding by the late 1980s, it reappeared in a different form: similar semi-organized trawler flotillas, this time Chinese, made similar incursions but to the far-western edges of Mexico’s Pacific EEZ.

As it was one of the nation’s only two destroyers, ARM Cuitláhuac still trained for use in a conventional conflict. The WWII 5″ main guns were fully operational and kept in supremely good condition, as were the WWII 40mm AA guns.

When ARM Cuitláhuac transferred it was still equipped with the WWII Type QGB sonar, a short-range active/passive set generally limited to one or two nautical miles. This was obviously obsolete already in the 1970s let alone in later decades. The WWII depth charge racks were rarely if ever mounted however the Mk6 K-Guns remained usable.

The Mexican navy changed its pennant number system several times after WWII. ARM Cuitláhuac was originally F-2, then IE-02, then E-02, and finally E-01.

ARM Cuitláhuac‘s sister-ship ARM Cuauhtémoc, the ex-USS Harrison, had briefly been renamed ARM Xicoténcatl before being discarded in 1982.

Meanwhile ARM Cuitláhuac remained in use. By the start of the 1980s, a new problem was beginning, one which would eventually become Mexico’s national tragedy, the drug war.

Drug smuggling at sea is quite different than the exciting speedboat chases of “Miami Vice”. In the 1980s – 1990s Mexican Pacific, drugs typically traveled in bulk aboard slow shrimp boats, “coasters” (mini-freighters), or tugboats. These could be bound for either the USA directly or to a Mexican cartel for an overland crossing of the USA’s southern land border. These vessels were slow, but it took having lots of warships at sea for a lot of the time to find, stop, and inspect them. The Mexican navy, like the US Coast Guard, considers maritime drug smuggling “a foe of all flags” and will interdict it anywhere, not just within the 12 NM national limit.

Much of the traffic was “intermodaled”. Here the smuggling trawler or tug either docked in Mexico’s central coast and unloaded into automobiles, or, split the load up at sea into smaller motorboats. Yet another wrinkle was exploitation of the hapless Guatemalan navy. Here the smuggling ship would anchor just south of Mexico’s border, intermodal the drugs into motorboats, crossing into Mexico via inland rivers, and then moving further north by road.

In all cases it was preferable to intercept the drugs on the high seas, before they were split up. ARM Cuitláhuac was ideal for this. The Fletcher class had been designed in 1939 to fight trans-oceanic wars at long operational ranges. ARM Cuitláhuac could sail from one end of Mexico to another, back again, and almost again a third time; without refueling. In more realistic setting a “box” of Mexico’s EEZ could be loitered in and searched repeatedly for both drug smuggling and EEZ issues. No upgrades to the ship were needed for this mission, and none were done.

slow road to replacement

By the 1980s, even though the drug menace was taking much of the navy’s time, there was a feeling among Mexican officers that maybe the fleet’s pendulum had swung too far away from traditional naval warfighting.

On 24 February 1982, Mexico purchased two FRAM-upgraded WWII Gearing class destroyers from the United States.

(ARM Netzahualcoyotl had been USS Steinaker (DD-863) during WWII. It would later end up being the last Gearing class in worldwide use.)

These had RUR-5 Asroc missiles, ASW homing torpedoes, upgraded sonar, and a helipad. It was intended that the two upgraded Gearings replace the two unmodified, obsolete Fletchers, and as mentioned earlier ARM Cuitláhuac‘s sister-ship was discarded. However the Mexicans decided to retain ARM Cuitláhuac in service alongside the two Gearings for an undetermined interim period, which would end up being longer than anybody imagined.

On 16 November 1993 Mexico purchased both of the US Navy’s Bronstein class frigates, a Vietnam War-era design light years beyond ARM Cuitláhuac.

(ARM Nicholas Bravo, the former USS McCloy (FF-1038) at sea.) (photo via navsource website)

With them in service it was planned that ARM Cuitláhuac would finally be decommissioned in 1994, however this was again pushed back as ARM Cuitláhuac was still in everyday use in the Pacific.

a declining asset, but still useful

ARM Cuitláhuac was obviously obsolete in every regard – yet, it remained tremendously reliable.

When the destroyer recommissioned into Mexican service during 1970 the rated top speed was 34 kts, meaning it had lost only 2 knots during its quarter-century slumber. By 1980 this had been reduced to 30 kts.

During 1984 ARM Cuitláhuac was declared ASW-incapable. The astern depth charge racks had rarely if ever been used by Mexico anyways and their mounting sockets were sealed. The WWII sonar was left unmaintained and unmanned. The Mk6 K-Guns were retained inactive, but their 3-round reload cages and arbor racks were removed and the firing pyrotechnics lockers deleted.

(The port side K- Guns after the ASW deactivation. During WWII there would have been a 3-round reload cage next to each along with shepherd’s staffs; curved booms to aid in refilling the reload cages. These were all deleted.) (photo by Vincente Romero for Sentinel Mexico website)

The changes reduced the crew size to 197, 16 officers and 181 enlisted. This was a 28% manning reduction from the WWII peak.

SEMAR is an office of the Mexican navy, roughly analogous to combining what INSURV and Naval Sea Systems Command do for the American fleet. During 1992 SEMAR issued a 12 kts speed limit for ARM Cuitláhuac out of concern for the steam lines and valves, now half a century old. The captain retained at his discretion faster speeds in a dire emergency.

The sluggish 12 kts was still sufficient for ARM Cuitláhuac‘s EEZ task and also the narcopatrol job. Many of the coasters, shrimpers, and tugs moving drugs in that timeframe could themselves only make 12 kts. If a faster radar contact ignored radio instructions to halt, it was prima facie a smuggler and a navigational position was radioed to faster assets of the US Coast Guard, Mexican navy, or the American DEA.

The 1997 – 1998 edition of Janes Fighting Ships stated that ARM Cuitláhuac was “…very active in drug enforcement patrols”.

relics on the “living fossil”

This section is not to ridicule the ship – as mentioned already above, the EEZ mission did not require modernizations and it would have been wasteful or even counter-productive for the Mexicans to have done so aboard ARM Cuitláhuac. Rather, this is a look at some things which were already long since extinct on the world’s seas when the destroyer finally left service.

the few upgrades

A very few modernizations were done, the most apparent being the main radars.

(photo via shipspotting website)

The above photo was taken during a visit to California, hence Old Glory at the courtesy position. Mexico replaced the woefully obsolete WWII main radars on the foremast with a Kelvin Hughes 17/9 search radar and a Kelvin Hughes 14/9 navigation radar. Mexico had a long relationship with that British company and these radars were used throughout the Mexican fleet for many years.

Other than modern auto-inflate lifeboats, the only other notable addition was four Oerlikon 20mm autocannons; these were also common throughout Mexico’s fleet and added in part just so crewmen could stay current in their qualifications.

gunfire control system (GFCS)

Quite remarkably, the WWII gunnery radars were never removed.

(Mk22 and Mk12 atop the Mk37 director of USS John Rodgers during WWII.)

(The same still aboard ARM Cuitláhuac in 2010.)

These WWII radars (the “orange peel antenna” of the Mk22 gave the Mk12 an anti-aircraft function) were long since out of service; many decades in the US Navy. They were aboard when the destroyer was sold in 1970 and were actively used by Mexico, as there are at least two photos of the ship at sea with the antennas temporarily ashore for cleaning and repair.

The Mk12 operated in the UHF band and would, by turn of the millennium standards, be simple to jam. However this was irrelevant to the EEZ patrol mission where such a sensor was not needed at all. In the unlikely event that ARM Cuitláhuac had to fight another conventional naval war it would be better to have it than nothing, meanwhile the extremely low odds of that ever happening made it uneconomical to replace.

For WWII warships with Mk37 GFCS directors transferred abroad after WWII, almost all had the Mk12/Mk22 combo already replaced by a Mk25 radar. The Mk25 itself was a legacy system by the 1990s, and by the end of the decade manned GFCS directors were themselves nearly dead.

It was not necessary to use these radars to fire the 5″ main guns and in fact the individual turrets could be fired without any GFCS input of any type, albeit less accurately.

The Mexican navy is quite adept at sourcing legacy spare parts like vacuum tubes and analog relays. However keeping these going must have been interesting. Not only was ARM Cuitláhuac the last Fletcher in the world, it was also the last user of the Mk37 + Mk12 & Mk22 combo.

Mk15 unguided ship-to-ship torpedoes

This is interesting because it illustrates that sometimes when things go away, they go away so quietly that it is later hard to pinpoint when.

When ARM Cuitláhuac transferred in 1970, the forward (Mk14) quintuple bank had already been removed but the aft (Mk15, with the blast hut) bank remained.

If anything was inside of them is an altogether different question. A first step would be determining if the United States in 1970, even had any Mk15s to offer Mexico.

Why Mk15 torpedoes went obsolete at WWII’s end was already covered earlier. At least formally, the Mk15 torpedo remained a US Navy weapon until 1956 with the withdrawal accelerating from 1958 onwards. Knowledge of the Mk15 was still required to advance in rank for torpedomen as late as 1961. The 1963 edition of NAVPERS 10006-A (the guidebook to reactivating mothballed WWII warships) still had instructions for quintuple tubes on destroyers. By 1965 the Mk15 torpedoes were finally gone from the American fleet.

A Mk15 cost $10,000 during WWII ($223,094 in 2024 dollars) so they were not cheap ordnance. Of the 11,000 ordered, 9,700 had been made before production halted and of those, 7,800 remained at WWII’s end.

Many Mk15s were made by Amertorp, a subsidiary of American Can Company in Chicago. During WWII this was a hybrid civilian-military facility, Naval Ordnance Plant Forest Park, IL. It also made air-dropped and submarine torpedoes. During the Korean War it ceased torpedo production and it was torn down in 1971. Legacy support was done by Naval Torpedo Station Newport, RI.

It is thought, but not certain, that the last active American warship still with warshot Mk15 torpedoes aboard was a Fletcher class destroyer, USS Kidd (DD-661) during 1964. This would seem to make sense as USS Kidd at that time was the Atlantic Fleet’s destroyer tactics demonstrator and was homeported at Newport, RI.

Contrary to how it sometimes seems, the US Navy does not prefer to sit on obsolete weapons. During the Cold War the first step was “1011’ing it” referencing an old Bureau of Ordnance paperwork form. This stated that an activity (squadron, base, division) neither needed nor wanted the ordnance and pushed the chain of command to make decisions on it.

During 1957 the US Navy did a disposal of excess WWII torpedoes. Admiral Frederic Withington said the US Navy still had more leftover WWII-built torpedoes on hand twelve years after the war than it had fired during it. This disposal was all “heater” (non-electric) types, presumably including Mk15s. In 1963, as the last Mk15s were fading from the fleet, the US Navy undertook a second survey of obsolete WWII torpedoes to be discarded, this being seven years before the ex-USS John Rodgers was sold to Mexico.

So without really having answered if any even still were around to offer, the second question is would any be offered in 1970.

During 1972 Congress formalized that WWII warships sold abroad should offer “a starter pack” of whatever it was that they were supposed to do; for example submarines ten or so torpedoes – any further quantities of which would then be at further expense. However this was two years after Mexico had already bought ARM Cuitláhuac.

Prior to 1972, there really was no rigid guidance for FMS sales. Sometimes the contract explicitly spelled out that (x) quantity of this or that ammunition was included, sometimes it explicitly stated that none was included; and sometimes neither was said. Often it fell upon the shoulders of the commander of the American naval base where the sold warship was reactivated to decide.

There was an assumption that a FMS-customer navy would already have WWII-era ammo. Usually this held true, for example in Mexico’s case, the 5″, 40mm, and depth charge ammo on a Fletcher were already in wide use aboard other classes in the Mexican fleet.

The Mk15 at the time of the sale was a “glitch in the system”: Mexico didn’t have any, it was already gone from the active American inventory, nothing Mexican before the two Fletchers could fire them, and nothing Mexico would ever acquire after could either.

Perhaps some still were warehoused in 1970 (NATO allies had Mk15s in use into the early 1970s). The most which could have come aboard ARM Cuitláhuac in Charleston was five individual Mk15s, and with just ten 21″ tubes in the entire Mexican navy it seems doubtful that any were ever bought.

(ARM Cuitláhuac during the late 1990s with the tubes finally gone.)

On the other hand the tubes aboard ARM Cuitláhuac appeared in immaculate condition up until their removal in the 1990s. It might seem strange to keep empty tubes aboard for so many years and then remove them close to the ship’s retirement.

(After the tubes were removed, the retractable loading crane from WWII remained.)

other misc. things

The pole shown below on ARM Cuitláhuac once carried USS John Rodgers‘s EW systems, which were added towards the latter part of WWII.

AN/SPR-1 was a passive warning system, its port and starboard antennas were angled 45° to capture both horizontally and vertically polarized Japanese radar waves.

AN/SPT-4 was the smaller active jammer on the pole. During WWII it was nicknamed “Rug” in the Pacific, in reference to project “Carpet”s AN/SPT-2, -3, and -5 designed to jam German radars in the Atlantic.

(USS John Rodgers late during WWII.)

These systems were already overtaken by technology when WWII ended, and the antennas (but not the pole) were removed when USS John Rodgers decommissioned. The obsolete gear was not reinstalled in 1970.

(photo via TodoPorMexico web forum)

Aboard ARM Cuitláhuac the pole was not getting in the way of anything and there was nothing new that could be installed on it to support the EEZ patrol mission. Aboard other Fletchers worldwide, other things were usually put there so it is extremely rare that this little bit of long-forgotten WWII electronic warfare kit survived.

This was on ARM Cuitláhuac‘s starboard deck. To the extreme left, the torched-off stanchion was once the support for the locker holding spare arbors for the Mk6 K-Gun shown. It was removed during the ASW deactivation. Under the “X” condition marker is a long-ago thing; the Fletcher class’s RAS trunk, which was used for UNREP (refueling at sea).

When the Fletcher class was being designed, refueling a warship in motion on the high seas was still a young art form. An oiler would pass over a hose to the Fletcher, with crewmen simply sticking the hose down the RAS trunk and securing it with a crude hand-tied rope noose. Later UNREP systems were obviously far more refined and safer.

USS John Rodgers, the future ARM Cuitláhuac, was an “early-war Fletcher” and in fact the last of those built by Consolidated during WWII. Above are early-war features: the rounded bridge with older window layout, the balcony which in later ships had an offmount AA director, and no Hedgehog ASW weapons between the upper forward 5″ turret and superstructure. Even on “early-war Fletchers” some or all of these things were changed during or after WWII.

end of service and unfortunate final fate

(ARM Cuitláhuac at San Francisco, CA in 2000, on one of its final voyages abroad.) (photo via navsource website)

ARM Cuitláhuac‘s final parent command was Zona X of Fleet VI headquartered at Lázaro Cárdenas, which would also be the port where it would meet its convoluted end. By 2001, Mexico had sufficient modern warships to finally retire this WWII destroyer which was the last Fletcher in service anywhere in the world.

On 16 July 2001, ARM Cuitláhuac was decommissioned. At 59 years of age, it had served 3 years under the Stars & Stripes and 31 years under La Bandera. The ship was moored at a military pier in Lázaro Cárdenas.

Beauchamp Tower’s attempted buy

Beauchamp Tower was a non-profit corporation in Milton, FL. Failed attempts to create WWII warship museums are not unique, but what made Beauchamp Tower stand out was its unusual premise.

In 2006 it was only 4½ years after 9/11 and a year after Hurricane Katrina, and “disaster readiness” was a hot buzzword in America. Beauchamp Tower proposed a scheme called “Enduring Service”. Here, several discarded warships (USS Howard Gilmore (AS-16), a WWII submarine tender, was also mentioned) would be acquired by Beauchamp Tower. This little fleet would then be put around America’s coasts as pierside museum ships – but with a twist. In time of disasters, these ships would spring back to life and quickly go the affected city as a recovery command post. The former USS John Rodgers / ARM Cuitláhuac would be “based” as a museum ship at Mobile, AL.

There were issues with the scheme, the main being that this was a service nobody at any level of American governance was asking for. Even if it were, to establish a sea-mobile disaster recovery command doesn’t require relic WWII warships. Any number of modern watercraft types would be more ideal. The US Maritime Administration was against the idea and it had little traction in Congress.

In any case the Mexican navy was pleased that a fitting and honorable home could be found for ARM Cuitláhuac. Via a 30 November 2006 decree of Mexico’s president Vincente Fox, the title of the ex-ARM Cuitláhuac passed from the Mexican navy to Beauchamp Tower, with a Mexican firm Representaciones Maritimas acting as the middleman. The agreement gave Beauchamp Tower 30 days to pay for the destroyer. The destroyer was towed from the naval pier across Lázaro Cárdenas harbor to the civilian granary wharf, a private quay belonging to the Almacenadora Mercader company.

(photo by Jennifer Szymaszek)

On 30 December 2006 Beauchamp Tower remitted $62,374.50 for the ship and its release from Mexican waters within 15 days. Here is where differing versions of events begin.

John Bergene, owner of the tug company E.J. Ventures, stated that in August 2006 he had been hired by Beauchamp Tower to tow the destroyer through the Panama Canal to Alabama. In September 2006 (which was before the transfer had legally been finalized) he had not been paid and contacted Beauchamp Tower. They stated because of Labor Day banks were closed but money would be coming. This seemed reasonable and the tug remained at Lázaro Cárdenas. After the holiday weekend, money did not come, and a week later it still had not. The E.J. Ventures tug remained, both because Bergene wanted to see the destroyer saved and because the calendar had already been blanked off. Finally fifteen days later, with no money, the tug departed for its next job.

Beauchamp Tower said that E.J. Ventures had angered and offended the Mexican authorities while in Lázaro Cárdenas and that, more or less, this is what had blocked the deal’s consumation.

As the year turned to 2007 the Mexicans worked with the middleman and suggested that the ex-ARM Cuitláhuac be towed to San Diego, CA; a shorter and much cheaper tow without the need for a Panama Canal transit. The response was, allegedly, that Beauchamp Tower was still adamant about the Mobile, AL location.

Back in 2006 the port captain of Lázaro Cárdenas had agreed to mooring the ex-ARM Cuitláhuac at the privately-owned granary quay as he was told it would be for no more than two weeks, probably just a few days.

By the end of 2008, two weeks had turned into two months and then into two years. Now he wanted the destroyer gone. If it were to sink it would possibly damage the pier. During July 2009 the captaincy started mailing trespass letters to Beauchamp Tower in the United States, who did not reply, and also filed a lien request in Mexican courts against the ship.

In the meantime, north of the Rio Grande, E.J. Ventures won a $800,000 lien on the destroyer for its unpaid tug job in 2006. The lien was “adversed”, a legal term meaning the collateral (here, the scrap value of a Fletcher class destroyer) was worth less than the total claim.

On 14 September 2009 the newspaper El Indicator Del Puerto stated that Mexican court proceedings were underway to condemn the ship.

attempted buy by The Last Patrol

A second USA-based military history group called The Last Patrol stepped in and itself attempted to acquire the former USS John Rodgers / ARM Cuitláhuac to be a normal museum warship in Ohio.

The Mexican authorities were cordial to the request but informed The Last Patrol of several particulars: the accrued wharf fees, liens, fines, plus interest on all of the above; would likely be around $2,000,000. As the window to export it out of Mexico had long since expired, a separate customs permit would be needed. There was the matter of the lien in the American court system which any new American owner would have to address. The ship still had asbestos aboard from WWII. Finally to tow it down the coast, through the Panama Canal, and up to the Great Lakes might double the $2 million cost yet again. The Last Patrol passed on the destroyer.

ship’s condition

When this process all began in 2006 it was assumed that ARM Cuitláhuac was in good condition. The Mexican navy maintains impeccable shipboard standards, at least as high as the US Navy if not even slightly more stringent. Moreover ARM Cuitláhuac had been active until the end including a voyage abroad several months before decommissioning. Meanwhile ARM Netzahualcoyotl, the last WWII Gearing class in use, was then still actively commissioned and in fantastic shape.

During 2007 an anonymous poster to an internet defense web forum stated that he lived in Lázaro Cárdenas and things were not as rosy as imagined. He said that ARM Cuitláhuac was in terrible shape, heavily rusted (he stated “a man might punch his fist through the hull”) and having been burglarized of brass and copper items; in addition to having some equipment removed by the Mexican navy after decommissioning.

Anybody on the internet can write anything they want, but there seems little reason to doubt him. During 2010 a former USS John Rodgers crewman visited the ship. It was unmaintained and totally unguarded; anybody who could access the commercial port could freely approach it. Many of the doors and hatches had been left open to the weather and there was significant rust.

(photo via navsource website)

the end

On 15 July 2010 a Mexican court ruled that the destroyer was abandoned property and awarded it to the Ministry of Communications and Transportation. The ruling freed the ship from all Mexican liens, as hazards to navigation are considered legally superior to civil claims. The tugboat company’s lien in American court was legally irrelevant to the Mexican court.

(This is perhaps the last photo of the ship as it was being prepped for scrapping.) (photo via warsearchers website)

This ministry studied several options to get the ship out of Lázaro Cárdenas:

1 – Return it to the US Navy. This would be the most honorable choice from the Mexican navy’s standpoint, and in practical terms would make the ship’s final fate somebody else’s concern. Unfortunately there was no legal avenue to do this. The United States retained some residual rights to WWII warships transferred by the MAP and SAP programs. However FMS sales were final.

2 – Find a home in Mexico. The Mexican state of Michoacán stated that it would not allocate taxpayer money to make the destroyer a museum ship at Lázaro Cárdenas. To make it a museum ship elsewhere in Mexico would require finding both an interested party and funds to tow it.

A university in Mexico expressed interest in converting the destroyer into a sea biology lab. However it estimated that even if it was no-cost donated to the university, repairing it enough to safely sail would exceed the cost of just buying something else.

3 – Discard it. Sinking it as a reef would perhaps generate some future tourist income however the delay to finding a suitable scuttling site, de-oiling the ship, and then getting the required environmental permits were not aligned with the court’s demand to expeditiously get the destroyer out of Lázaro Cárdenas. The final option was to scrap the ship in Mexico.

The newspaper La Jornada Michoacan stated that on 2 August 2010, the Ministry of Communications and Transportation had decided to scrap the ship, with the title transferring on 28 August 2010. The ship was cut up at Lázaro Cárdenas with the steel recycling being completed in April 2011.

postscript

My interest in this destroyer actually originally started with trying to find the last time an American warship had WWII ship-to-ship torpedoes still aboard. The Mk15 was not a trivial thing; during the early 1940s it was a huge line item on the US Navy’s annual munitions outlay budget. The way that the Mk15 slid into the administrative abyss is illustrative that within a military as large as the USA’s, sometimes things just silently go away so slowly that at the end nobody notices.

I am unsure how much the general public is aware of EEZs or what a potential issue they are.

(ARM Seri had been USS Cocopa (ATF-101) during WWII. When the US Navy decommissioned it after the Vietnam War, Mexico purchased it as a combined EEZ patrol ship / tug. As of 2020 it was still in service.) (photo by Gene Kennedy)

Before 1982 there was no international agreement on EEZs, beyond what a nation claimed and was willing or able to patrol. The “agreed framework” is barely that, unenforceable and sometimes still disputed.

Just as one generic example, Lebanon disputes Israel’s EEZ in its entirety; a side effect being that if Israel’s EEZ was erased Cyprus’s EEZ would inadvertently shift due to the split-the-difference rule. Cyprus already has a separate EEZ dispute with Turkey. Meanwhile Turkey has another EEZ dispute, with Greece, as Turkey does not recognize the extension-by-islands rule and measures 200 NM from “continental landmass”.

“Islands” in the 1982 framework are natural geographic features permanently dry at high tide. They need not be inhabited. For example during 1978 the USA / Mexico EEZ “split difference” shifted a tiny bit due to Isla Bermeja, an uninhabited cay in the Gulf of Mexico once charted by Spanish galleons, finally eroding beneath the tideline. That EEZ shift happened with no fuss. Other instances are not as friendly.

Numerous Asian navies do not recognize the high tide line, but rather low tide, which thereby qualifies some sandbars and reefs. These then greatly expand the claimant’s EEZ and often, also truncate somebody else’s EEZ from the split-the-difference principle. China goes further and considers certain man-made structures as “islands”.

Outside of a few obvious flashpoints like Taiwan, many naval observers worldwide feel it likely that the next major war at sea will start as a EEZ dispute.

(A parade float of ARM Cuitláhuac during a 2021 celebration of the Mexican navy. The destroyer is still remembered as “El Leal”, a reliable warship always ready to go to sea.)

gotta wonder if the ship was in any tele novas.

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOL I’m not sure.

LikeLike

Fantastic article, one small nitpick is that the name of the British sea forts is Maunsell, not Mounsell. Named for the designer, Guy Maunsell.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for catching that, I have corrected it.

LikeLike