Bei’an in northern China was for many years “Gun City, PRC”; churning out huge numbers of cloned WWII-era firearms before switching to China’s clone of the AK-47.

(American soldiers examine a captured Type 50, the Chinese clone of the WWII Soviet PPSh-41, during the Korean War.) (US National Archives photo)

(This monument in modern Bei’an honors the 9,006,116 guns made at Factory #626.) (photo via Xinhua news agency)

location

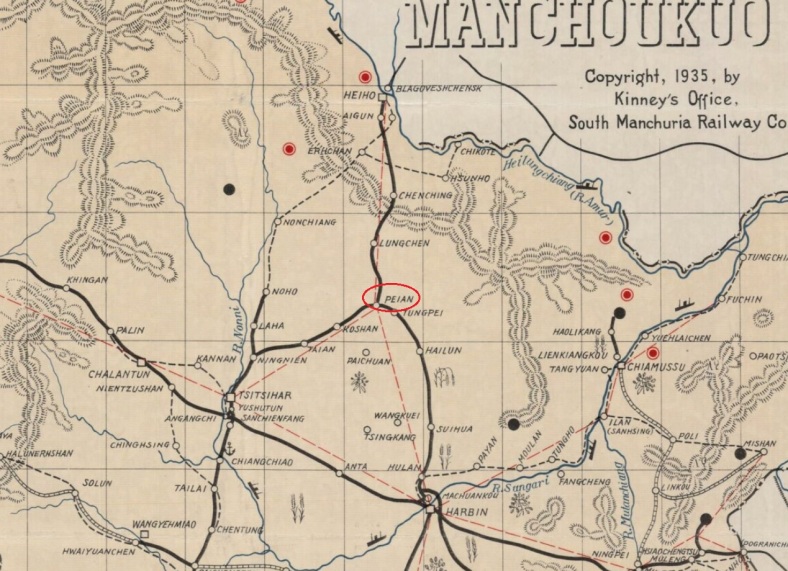

Bei’an is a small city in northern China. During WWII it was a stop on the South Manchuria Railway but otherwise of no importance.

(A pre-WWII SMR map showing Bei’an, which was known as Peian at the time. This map possibly distorts its importance as during WWII it only had twelve paved roads.)

(Location in the modern PRC.)

During the 1930s, when Japan controlled the region via its puppet state of Manchukuo, there were plans to industrialize the little city which never came to fruition due to WWII.

The Soviet army overran Bei’an during August 1945 during its brief conflict with Japan which closed out WWII. During the Chinese Civil War (1945 – 1949) Bei’an was held by communist forces the whole time.

origin

Mukden Arsenal opened in Fengtian (later Mukden, today Shenyang) in 1921. During WWII Mukden Arsenal made a wide array of products for the Japanese military; anything from Arisaka rifles to machine guns to ammunition to field artillery to bayonets.

Mukden Arsenal survived WWII but was looted by the Soviets during 1945. It was restored by the KMT (nationalist Chinese government) and reopened as 90th North China Arsenal. During the Chinese Civil War, it made submachine guns and rifles for the nationalists. Communist troops overran the arsenal on 1 November 1948. A month later, they reopened it as Shenyang Dawn Arsenal.

How Bei’an’s “Gun City” story unfolds begins in Shenyang with a May 1949 bombing raid by the ROCAF (nationalist air force). A flight of WWII-veteran B-24 Liberator strategic bombers attempted to eliminate Shenyang Dawn Arsenal from the air. The ROCAF air raid failed (unfortunately it did destroy 170 civilian buildings in Shenyang). None the less, the possible loss of such a defense manufacturing capability in a single day shook the communist Chinese leadership.

During February 1950, Chairman Mao was returning from a trip to the Soviet Union by train and stopped in this region. He decided to diversify the locations for making weapons away from Shenyang, into what was called the Northeast Ordnance Bureau.

three-way division

Northeast Ordnance Bureau chose Tsitsihar (today Qiqihar) for artillery, a tiny town called Nianzi for ammunition, and Bei’an for firearms. On a map of northeastern China the three made a rough triangle.

The 1950 plan was that once each of the three arsenals opened, they would eventually match and surpass their “core competency”s capacity at Shenyang Dawn Arsenal, and then perhaps diversify into one or both of the other competencies.

In the PRC’s numbering system, factories were assigned a number with factories making ammunition ending in a 1, and factories making guns ending in a 6. (This system deteriorated and was eventually abandoned.) The new gun factory at Bei’an was Factory #626, and given the cover name Qinghua Tool Factory.

(The original proofmark.)

(The later proofmark. Some arsenals in the PRC omitted the center digit for security reasons.)

In late 1950, Shenyang Dawn Arsenal sent 1,358 pieces of production machinery to Bei’an, along with 1,631 employees and 800 wives and children. Another 700 machinery pieces were received from elsewhere in China. The conditions for establishing a gun factory were terrible. Heilongjiang (northern Manchuria) is bitter cold in winter. There was no existing infrastructure in Bei’an, for example most of the machinery was hand-dragged on sledges from the WWII South Manchuria Railway station to the site of the new factory. There was no housing for employees. A defunct WWII Imperial Japanese Army outpost was used, however the buildings had been abandoned since August 1945 and were in poor shape (some had snowdrifts inside when residents moved in). Even this was not enough and a former Japanese cavalry stable was converted into a dormitory.

Finally, like in any big move, some things got lost. Most critically for what was to come, lost in moving was Shenyang Dawn Arsenal’s PPSh-41 blueprints.

first guns at Bei’an

By 1 February 1951, 7 acres² worth of factory space had been built and production could begin. Four types, all WWII designs, were the first to be made.

Factory #626 made an unlicensed copy of the WWII American M2 carbine. It fired the .30 Carbine cartridge. Introduced late in WWII, the M2 was the select-fire version of the semi-auto M1.

(Chinese clone of the M2.)

Factory #626’s M2 clones had problems and apparently never received an official nomenclature. Only 300 were made.

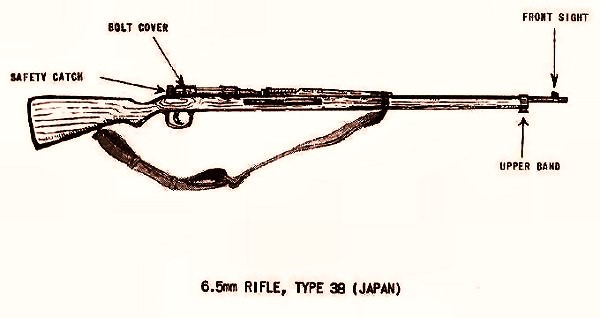

At the same time, another gun was being run at Factory #626: the “Big Cover Three/Eight”, aka the Arisaka 38, WWII Japan’s 6.5x50mm predecessor of the 7.7x58mm Arisaka 99. The rifle’s Chinese nickname came from its dust cover.

(Communist star on the upper receiver of a “Big Cover Three/Eight”.)

The history of Japan’s Arisaka 38 in China is long. During 1924 the warlord Zhang Zoulin (founder of Mukden Arsenal) bought 46,000 Arisaka 38s from Japan. This started a bidding frenzy amongst other warlords (quite lucrative for the middleman, Japanese Taiping Company) and 250,000 Arisaka 38s were commercially introduced into China during the 1920s. Mukden Arsenal began making Arisaka 38s in 1932 and switched production to the Arisaka 99 only in 1944, being the last imperial arsenal to switch during WWII.

Meanwhile China’s Shanxxi Arsenal began producing an unlicensed Arisaka 38 copy, the Six/Five Rifle, for the Chinese army. These were of poor quality, with production ending at 108,000.

At WWII’s end in 1945 both the nationalists and communists received huge numbers of surrendered Japanese Arisaka 38s along with unimaginable quantities of 6.5 Arisaka ammo. During the brief time the nationalists held Shenyang, the former Mukden Arsenal made the Type 45, a prewar Mukden Mauser rechambered from 7.92 Mauser to 6.5 Arisaka. Meanwhile a factory on the communist-held Shandong peninsula began making an actual Arisaka 38 copy (confusingly also called Type 45) in 1947.

(Communist PLA soldiers with a M1A1 Thompson and Arisaka 38 during the 1945 – 1949 Chinese Civil War. The tommygunner is wearing an ex-Japanese Tetsu-bo.)

So in 1951 it was not strange that the People’s Liberation Army would be accepting more Arisaka 38s. There was still huge amounts of ammo and the rifle’s traits were known. There were still 4,000 Arisaka 38s or clones / derivatives in frontline PLA use in Korea during 1953 and the last did not leave CPC Militia use until the 1970s.

(US Army Korean War handbook drawing of an Arisaka 38.)

The third WWII gun Factory #626 started off with was the “rifle of many names”. Officially the Type 24, in English it is commonly called the Generalissimo or the Chiang Kai-shek Rifle. In nationalist Chinese use, it was nicknamed the Zhongzheng. In the modern PLA nomenclature lineage, it is the Type 79.

The Type 24 is a near copy of the Mauser Standardmodell, of which the Chinese Tax Police bought 10,000 before WWII. This bolt-action rifle fired the 7.92 Mauser cartridge and in look, form, and function was similar to WWII Germany’s 98k.

About 400,000 were made during WWII and another 200,000 afterwards. During WWII nationalist China planned on making this the nation’s standard rifle, replacing the Hanyang 88. That did not pan out and Hanyang 88s not only fought all of WWII but also the Chinese Civil War.

Post-WWII production was centralized at Chongqing and on Taiwan, and largely ended in November 1949. It is possible that idled tooling from Chongqing was sent to Bei’an in 1950. By 1951 this is not really what the PLA was looking for but it was better than getting nothing.

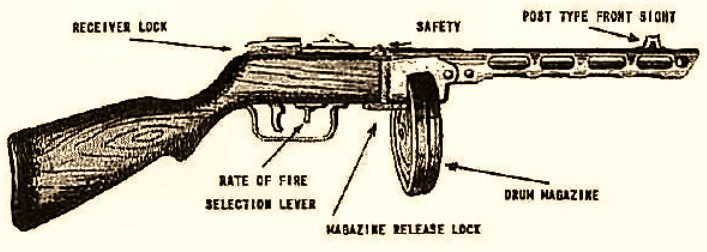

Finally, the fourth thing factory #626 was making was the WWII Soviet PPSh-41 submachine gun.

the Type 50

(A captured Chinese Type 50 submachine gun.) (photo via The Smithsonian)

the WWII original

Along with the T-34 tank and Il-2 Shturmovik plane, the PPSh-41 submachine gun is one of the iconic items of the USSR during WWII.

(Soviet soldier with PPSh-41 during WWII.)

Georgy Shpagin designed this firearm as a less expensive choice compared to other early-1940s submachine guns. Production began in November 1941, five months after the German invasion, and ramped up tremendously during 1942. During WWII about 6 million were made.

The PPSh-41 was 2’9″ long and weighed 8 lbs empty, 12 lbs with a full drum.

The PPSh-41 was select-fire, either single-shot or full-auto at 1,250rpm cyclical. It fired the 7.62x25mm Tokarev cartridge (1,600fps muzzle velocity); the same ammunition as the TT-33 pistol and the PPS-43 submachine gun. It used either a 71rds drum or a 35rds box magazine. The virtues and vices of these are described below.

Besides the drum magazine, an identifying trait is the steel barrel jacket which has the front end canted. This was intended to limit muzzle rise in full-auto.

The USSR began supplying PPSh-41s to communist Chinese troops at the end of WWII in September 1945.

China’s PPSh-41 clone, the Type 50

After the 1948 communist capture of Shenyang and the reopening of the former nationalist 90th North China Arsenal (Mukden Arsenal during WWII), domestic manufacture of the PPSh-41 began there late during 1949. Some drawings, but not complete ones, were provided by the Soviets. The balance was done through reverse-engineering.

Reverse-engineering is often portrayed in military literature as a simple thing but it is anything but that. A rifle, tank, howitzer, or whatever; has to be first disassembled into its smallest constituent parts of which each needs to then be measured in three dimensions with precision. Next back-calculation is needed to determine how specific parts flex, expand, or fail under stress. The amount of raw materials and time needed to make each part has to be determined. Finally the whole thing needs to be reassembled in a job plan that is repeatable.

During 1950 Shenyang Dawn Arsenal’s PPSh-41 copy gained official approval as the Type 50 in PLA nomenclature.

(Type 50 made at Shenyang Dawn Arsenal during October 1950.)

As described earlier, most of Factory #626’s “start-up” was extracted out of Shenyang Dawn Arsenal during 1950, including some Type 50 jigs and dies. The literature which should have accompanied them was lost en route.

Meanwhile, the Korean War to China’s south had begun on 25 June 1950. China initially stayed out of the conflict but moved the PLA’s IV Army Group to the border. It didn’t look like they would be needed, as by late summer North Korea was winning handily and had the Americans boxed into a small pocket around Busan.

In Bei’an replacement volumes of drawings and jobflow instructions were requested from Shenyang. In the interim Factory #626 got to work without them during 1950, via reverse-engineering.

Alongside the bolt-action rifles described earlier, “tinker-production” of Type 50s began in 1950. These were either KDKs (knock-down kits, parts made elsewhere but assembled in Bei’an) and gradually more completely-made guns altogether by Factory #626.

On 15 September 1950 Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s amphibious assault at Inchon dramatically swung the Korean War towards the USA’s favor. By 1 October, American troops had crossed the prewar border and were advancing north towards the Yalu river and China. As the North Korean army continued to crumble, China entered the war on 19 October 1950 as 200,000 men crossed the Yalu. Many of them were armed with PPSh-41s supplied by the Soviet Union.

It was apparent that the Korean War was not going to end soon. China would be needing a lot of submachine guns, and fast. As 1950 ended, Northeast Ordnance Bureau decided upon the Type 50, the PPSh-41 clone, as the best option for mass production.

During March 1951 Factory #626 received orders for wholesale mass production of the Type 50 to commence as soon as possible; with ideal output being between 7,500 – 9,000 per month. This would be a massive jump, as at the time, the factory was making Type 50s in a near-artisanal way, little better than one-by-one. Factory #626 foreman Mr. Shang Yaowu later recalled that ironically, the day he got the gigantic order, he was preparing an instruction to discontinue the Type 50 in Bei’an as he felt it unsuitable for his factory.

In April the project began. Everything else at Factory #626; all the bolt-action rifles, were discontinued. Over an eight-week span, 1,200 documents were either re-obtained from Shenyang Dawn or made from scratch. These were blueprints of everything down to the smallest rivet, along with assembly instructions, jobflow plans, etc.

In early June 1951, the first batch of 2,628 Type 50s left Factory #626 on a train headed to Korea and the effort was a success.

a look at Factory #626’s Type 50

In all but the smallest details, a Type 50 is identical to a WWII-made Soviet PPSh-41. The most immediately apparent difference is that the WWII original used a u-notch rear sight while the Chinese copy has a round aperture. It is attached with countersunk rivets instead of the button-head type in the PPSh-41.

(Magazine well of a Type 50.)

Chinese Type 50s lack the fillets around the magazine well found on PPSh-41s made during the second part of WWII in the USSR. PPSh-41s made early in WWII sometimes had the sheet metal around the well distort if a soldier leaned on the drum magazine while laying prone, so the extra steel was added. The Chinese omitted this to keep production as fast as possible.

(Trigger and selector on a Type 50.) (photo via Rock Island Auctions)

An oddity unique to Factory #626 was that some Type 50s had furniture of two pieces of lumber. This allowed younger timber to be used for firearms production, and was similar to Japan’s WWII Arisaka rifles which did the same thing for the same reason. The two pieces were glued together. During the Korean War the glue often failed and most were later restocked with one-piece furniture.

Chinese firearms of the Cold War are not exactly world-renown for high quality; the less said about that the better. However Factory #626 made the Type 50 with equal or superior standards to the WWII PPSh-41. Each lot had examples drawn for testing including a “sacrificial lamb” which had 10,000rds continuously fired, two-thirds of the expected 15,000rds maximum lifespan. Guns were tested in ambient air between -39°F to 122°F to simulate expected climates in Korea.

Like the PPSh-41 the Type 50’s safety was on the right side, sliding inwards to safe and outwards to fire.

The selector was inside the triggerguard ahead of the trigger. When pushed backwards into single-shot, the Type 50 operated like a blowback semi-auto handgun.

When pushed forward to full auto, a disconnector attached to the sear above the trigger engaged. With the Type 50 in battery, pulling the trigger contacted the firing pin, with the bolt then recoiling back. As it passed the upwards-facing port, a little ejector spring around the pin pushed the empty cartridge against an angled piece, spitting it upwards. The mainspring behind the bolt reversed bolt motion. As the bolt passed forward over the magazine well, a round was stripped and chambered, then fired as the pin made contact again, restarting the cycle. This repeated until the soldier released the trigger or ran out of ammunition.

(official US Army drawing)

Cleaning the Type 50 was no different than a WWII PPSh-41. A lock at the extreme rear of the receiver was pushed in, allowing the barrel and chamber section to pivot on its hinge and the bolt and mainspring to be removed.

magazines

During WWII the image of a Soviet soldier with a drum magazine on a PPSh-41 was iconic. The 71rds magazine itself had a hidden history during WWII. Earliest production drum mags had no problems. Those made during 1943 did, however. The drum mag was stamped steel only ½mm (0.0197″) thick and sometimes refused to engage the well. The USSR set about an exhaustive quality improvement program whereas by 1944, drum magazines again had no issues.

(A Type 50’s two magazine types along with the little hand tool included with the firearm.)

To load a Type 50 drum, the retention tab was swung away and the axle pushed to slide it from lock to open. The cover was then pulled off (usually, pried off, to be more accurate) and a central knob was twisted counter-clockwise to reset the conveyor. Each of the 71 cartridges had to be then inserted one-by-one and the magazine reassembled. Inclusive of its cloth bag, a loaded drum weighed 4¼ lbs.

China’s 1950s experience with Type 50 drums mirrored that of the Soviet original during WWII. The earliest production at Factory #626 had no problems. However subsequent batches had serious problems, usually the same issue as WWII: any given drum would not necessarily fit into any given Type 50, even if both were within factory tolerances.

Unlike the Soviets, the Chinese did not rectify the issue. Instead during 1952, drum mag production ended in favor of the alternate 35rds box magazine. Chinese drums already made continued in service and WWII Soviet-made PPSh-41 drums could be used as well, assuming they fit in a particular Type 50.

(South Korean soldier with a captured Type 50 and captured Chinese logistics trailer.)

The US Army Bureau of Ordnance issued a report, soon corrected, that Type 50s only worked with the WWII box magazine. Despite the retraction, the error continues to be repeated sometimes today.

markings

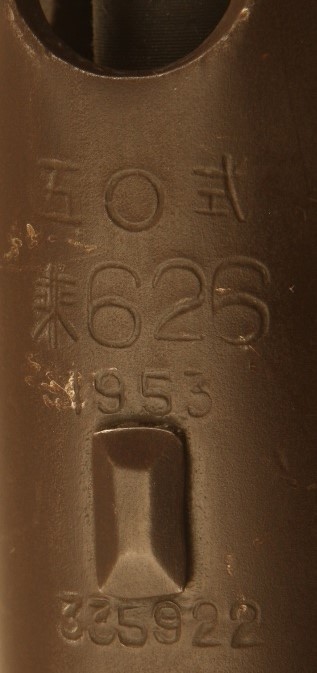

Type 50s were stamped with Wu Ling Shí (Five, Zero, Formula) meaning Type 50. Below this was the Factory #626 proof, and below it the production year.

Behind the trunnion embrasure is the serial. The last four digits of the serial are also stamped on the rear bottom of the receiver.

The Type 50 below, which is one of several like it captured during the Korean and Vietnam wars, has the normal Type 50 first line but then Sān (three) Er (two) with a communist star between them, with the production year on the third line.

Even with the center digit security-omitted (as Factory #626 did to “66”), “32” does not equal any military factory code in the PRC’s system. It is possible that during the Korean War, Factory #626 shipped KDKs to small civilian machine shops for final finishing and that these rare examples were of that.

differences from North Korea’s clone

(North Korean Type 49 markings for comparison.) (photo via Forgotten Weapons website)

North Korea also cloned the PPSh-41 as “Type 49”. Besides markings, these were usually of cruder construction and always used a drum magazine.

Thus during the Korean War from late 1950 onwards, WWII Soviet-made PPSh-41s were used by both North Korea and China, North Korean Type 49s by North Korea, and Chinese Type 50s by both China and North Korea.

end of production

With the Type 54 coming online, Type 50 production tapered off during 1953. During December the last left Factory #626. Total production at Bei’an was 358,000 over the 32-month span, an average of 2,576 every week.

(Type 50s remained in PLA service through the 1960s and with CPC Militia and reserve forces, into the 1980s.)

the Type 54

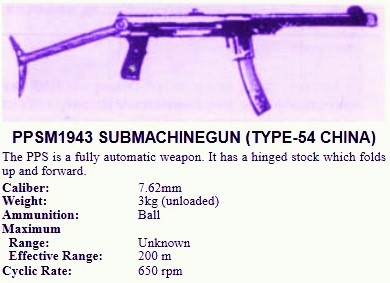

(Type 54 submachine gun.)

the WWII original

The USSR’s Pistolet-Pulemet Sudaeva 1943 was, along with Great Britain’s Sten, the crudest Allied submachine gun of WWII and probably one of the crudest military guns of the 20th century. None the less, it was a success. During WWII between 1.1 to 2 million PPS-43s were made; the Soviets themselves were unsure exactly how many.

The PPS-43 was 2′ long with the 8″ stock folded in, and weighed 6½ lbs. Like the PPSh-41, the PPS-43 used the 7.62x25mm Tokarev cartridge. It used a 35rds box magazine; there was no drum option. It was full-auto only.

(Soviet soldiers with PPS-43s during WWII.)

Other than the bolt and the barrel, practically the whole firearm was stamped sheet metal. For example the upper receiver housing and barrel shroud are one continuous stamping. Assembly was entirely either welding or simple riveting.

The PPS-43 was an emergency WWII weapon and could be made by unskilled laborers in bad conditions. Some were made inside Leningrad during the siege. Soviet production ended in June 1945.

China’s PPS-43 clone, the Type 54

Like the PPSh-41, the Soviet Union began supplying communist Chinese forces with PPS-43s after WWII for use during the Chinese Civil War.

During November 1951, Factory #626’s operations manager, Mr. Sun Yun-long, was summoned to Beijing. There, he was informed of policy changes within the PLA, and what would be a huge new task for Factory #626.

One issue which bedeviled the KMT (nationalist Chinese) army during WWII and then again during the Chinese Civil War, was a severe lack of standardization. For any given thing: mortar, rifle, machine gun, etc; instead of having a “standard” and a “substitute standard”, there were three or four “standard”s and at least that many, sometimes twice over, oddballs of varying origins and calibers in large-scale service simultaneously. As the communist People’s Liberation Army entered the Korean War, the PRC’s leadership saw it sliding into this bad habit.

To this, a decision was made to standardize weapons procurement on just 18 designs. One of these, the submachine gun category, was to be the USSR’s PPS-43.

The command in 1951 must have sounded like a nightmare to Factory #626’s management. For starters, not only was the PPS-43 not in Chinese production anywhere, the Soviets had not even provided any blueprints. Secondly, there would be no lull – Factory #626 would taper off the PPSh-41 clone as the PPS-43 clone’s production ramped up; so for a while anyways two guns would be in mass production. Finally, the end output was to exceed what the factory was currently at.

rationale

For anybody familiar with WWII submachine guns, on its surface this decision is perplexing. The PPSh-41 is clearly superior to the PPS-43; even without the added hardships mentioned above.

The Chinese looked at several things:

1 – Assuming success, the cheaper PPS-43 would have need fewer man-hours each even as more workers were assigned to Bei’an; thereby resulting in much greater end output.

2 – With the decision to abandon the Type 50’s drum magazine, the PPSh-41 clone lost its advantage in ammunition capacity.

3 – Chinese troops in Korea were already using both PPSh-41s and PPS-43s supplied by the USSR. Overwhelmingly the latter was more popular with enlisted soldiers in the field. In heavy winter coats, the PPS-43’s folding stock was said to allow free use of both arms with the gun slung, while the PPSh-41s length did not.

reverse-engineering the PPS-43

As described earlier, reverse-engineering is not as simple as military literature sometimes paints it. Except with the PPS-43, it sort of was just that simple.

Including pins, rivets, and springs there are fewer than four dozen pieces in a PPS-43, many duplicates or triplicates of each other.

(To field-strip a Type 54, a metal thumbtab at the rear allowed the upper half to pivot off the lower and the bolt assembly came out. That was the extent of it.) (photo via Jaybe-Militaria)

Factory #626’s WWII-vintage template gun was a PPS-43 manufactured at the NKMV Factory in Moscow during 1945. Once measurements had been done in 1951, the gun was such a simple thing (except for one step, described below) that in all likelihood the Chinese just played around with stamping presses until the metal bent the correct way.

a look at Factory #626’s Type 54

There were no differences on a Type 54 compared to a WWII PPS-43.

(Type 54 with stock extended.) (photo via IMA-USA)

One feature notable on either gun is a piece of stamped sheet metal ahead of the muzzle.

During WWII the Soviets intended this to function as a crude muzzle brake, in that some of the gasses exiting the muzzle would “catch” this sheet metal piece, dampening felt recoil.

(Type 54 with the stock folded.) (photo via IMA-USA)

The safety was a stamped metal finger-lever outside and to the right of the triggerguard.

With a magazine inserted, the charger (a tab of stamped metal, shown above) was pulled. Squeezing the trigger contacted the firing pin. The bolt’s weight momentarily slowed the start of its backwards motion enough for chamber pressure to subside, upon which the spent casing ejected. The mainspring, which ended at a crude “buffer” (a chunk of leather), reversed the bolt’s motion which chambered the next round. Firing continued as long as the trigger was held. A full magazine emptied in 3½ seconds. If the soldier chose not to dump the whole magazine, PLA practice was to eject it anyways and insert a full one.

(These are actually South Korean soldiers posing for an enemy uniforms and equipment guide. Both have WWII Soviet-made PPS-43s, not Chinese Type 54s; although the guide presented them as such. The soldier at right has a WWII Imperial Japanese Army canteen; these were used by both North Korea and China during the Korean War.)

The satchel-style magazine bag seen above held four Type 54 magazines. A later type held three, and could be worn as a webbing accessory.

production at Factory #626

In Bei’an, 3,000 additional employees were authorized for 1952 – 1953, some skilled and some general labor. The skilled ones were sent straight to work. For the unskilled positions, existing warehouse workers, etc were given a crash course in gun production and promoted, while new arrivals took their old jobs. Very little new machinery was provided for this massive new requirement, so as much as possible existing Type 50 tooling was reconfigured to make the PPS-43 clone.

As mentioned earlier almost all of a PPS-43 was stamped. Two extraneous processes were the bolt (machined off a solid steel billet, with its mainspring drawn wire) and the barrel’s rifling.

During WWII the Soviets broached the PPS-43’s rifling. Broached rifling uses a hardened steel cutting head on the end of a rod, with the head having multiple cutting surfaces. This was inserted into a heat-treated blank barrel. A broaching machine is physically big (by definition it is at least 201% of the barrel’s length and usually longer) and most WWII gun factories had limited stock of them.

At Factory #626 a gunsmith named Zhao Ruizhi, contemplating the issue with no available jobflow guide, considered how the mass production goal might be achieved. He invented a system where instead of broaching in the PPS-43’s rifling, a raw (blank and untreated) barrel had its interior flashed with a cheap copper alloy. A metal extruder was modified to draw through the barrel, rifling it and removing the flashing. It was then heat-treated. This produced barrels equal or better than the WWII method and was 1¼ times faster.

During the winter of 1952 – 1953, the final kinks in the cloning and assembly process were resolved. Production began and by June 1953, the PPS-43 clone’s production was at a level that the tapering-down of Type 50 production could begin.

This would come too late for this “new” Chinese submachine gun to see much Korean War action, as that conflict ended in July 1953.

the “replica” becomes the Type 54, and Soviet involvement

China assigns a “Type __” nomenclature only when a firearm has been designated for use, passes design reliability standards, is achievable through mass production, and enters frontline PLA service.

The PPS-43 clone slowly crept into production during the spring of 1953 and its steps were out of order. It had already been selected but was, due to the Korean War, being rushed straight into mass production even as jobflow planning was still underway. Detailed more below, these early clones were called “Replica 43s”.

After the Korean War ended, Soviet advisors came to Factory #626. They were adamant that their own WWII processes be used instead (for example, rifling broaching instead of the actually superior Chinese method) and during the early spring of 1954 the Chinese PPS-43 project was “resurveyed”.

In layman’s terms this would usually mean starting over from scratch however that was obviously not completely necessary here; for example existing tooling could be used and worker experience already gained was not lost.

In April 1954 the gun gained official People’s Liberation Army sanction as the Type 54 and all made thereafter were officially under that name. In practice, all were usually called that regardless of when they had physically been made.

markings

At top is Fang, in this context it means “imitate” as a verb in English.

On the next line is Si (four), Sān (three), Shí (formula), and underneath that the production year, here 1955.

Thus in English it would read “Replica 43 Type”.

The serial numbers on Type 54s are nearly indecipherable. Often there is a “prefix digit”, followed by either a space or a hyphen, and then what looks to be the main serial number. Sometimes the “prefix digit” is altogether missing and the serials themselves appeared to have restarted at least twice. Factory #626 was the overwhelming main, if not exclusive, producer of this submachine so it probably doesn’t indicate any geographic difference.

(A simple 5-digit serial from 1954 with no prefix.)

The markings are often physically sloppy; for example above the “4” in the year 1954 is a different die font than “195” and the serial is misspaced and off-centered.

Supposedly during the Vietnam War, the US Army captured Viet Cong Type 54s lacking the Fang letter and reading Wu Si Shí (Type 54); this obviously being due to the Soviet involvement at Factory #626. Photographs of such are lacking, and there are known examples of Type 54s made in 1954 and 1955 still with “replica”.

(A 1955-made example still with the original format.) (photo via Small Arms Review website)

service and end of production

During WWII the USSR intended the PPS-43 as an emergency project. They wanted as many as possible as fast as possible as cheaply as possible, for immediate use against the Germans. To that end the PPS-43 was a success.

When the Chinese cloning project started in late 1952, the objective was similar. China needed huge numbers very fast for combat in Korea. However the Korean War ended only a month after Type 54 production first hit full stride.

Now, this submachine gun did not look so great. With the emergency gone, the crude Type 54 wasn’t necessarily the most ideal weapon for the standing peacetime PLA.

Meanwhile in August 1954 the Soviets sent blueprints and technical data to Bei’an for starting AK-47 production at Factory #626. This was done (as the Type 56) during late 1955 – early 1956.

(Marshal Ye Jianying with a Type 56 at Factory #626. The AK-47 clone replaced the PPS-43 clone in production.)

With the Type 56 in full production, Type 54 manufacturing rapidly concluded in 1956. The total number built over three years is not certain but is thought to be between 400,000 to half a million. Other estimates are higher.

Although the Korean War was over, these guns were used by the peacetime PLA. Select-fire assault rifles like the Type 56 made the submachine gun role largely redundant, but they were a useful replacement for WWII bolt-action carbines still in use by supply, artillery, etc units. They also found niches in airborne and naval infantry units.

(Chinese soldiers with Type 54s during the 1960s.)

(Chinese paratroopers with Type 54s during 1962.)

Type 50 and Type 54 in service abroad

China later exported some of its submachine gun inventory as it was phased out of PLA use during the late 1960s and 1970s. Type 50s were widely seen in North Vietnamese and Viet Cong use during the Vietnam War, as were Type 54s. The latter have been observed in combat as far away as Cambodia, Rhodesia, and Kosovo.

(During February 2018 police in Durres, Albania confiscated this Type 54. During the Cold War, the communist Albanian army used Type 54s under the nomenclature “Armë zjarri automatik kinez, Mod 54” or Chinese automatic gun, Model 54.) (photo via balkanweb)

(Submachine guns captured by the US Army in Vietnam: a Chinese-made Type 50, then a North Vietnamese-made K-50, then a French-made MAT-49.)

(Viet Cong soldier with Type 54.)

(Taken from a 1990s US Marine Corps handbook on the North Korean military, this shows Type 54s still in use with that nation.)

postscript: the decline & fall of “Gun City, PRC”

The start of Factory #626’s eventual demise had nothing to do with the factory itself, which throughout the early 1970s continued to make Type 56s (the AK-47 clone). It also made the Types 51 and 54, China’s clones of the WWII Soviet TT-33 handgun.

(Type 54 made at Factory #626. This was a clone of the WWII TT-33.) (National Rifle Association photo)

During 1962 relations between the planet’s two biggest communist nations, the USSR and the PRC, began to deteriorate. This worsened throughout the decade and climaxed with an armed skirmish at Zhenbao Islet in 1969. After this the two nations were hostile to each other.

When Chairman Mao had stopped in northern Manchuria during February 1950 and decided to diversify gun production out of Shenyang, Bei’an seemed perfect. It had good railroad access and was safely nestled deep in the northeast PRC, effectively protected on three sides by the friendly USSR.

Now 20 years later this location’s blessing became a curse. Only 76 miles from the USSR border, Bei’an would be highly vulnerable if the two nations went to war. Soviet advisors had been stationed at Factory #626 during the mid-1950s and not only knew of the factory, but even its floor plan.

During the 1970s it was decided to move Factory #626 from Bei’an to Xuchang, deep in central China. In 1979, roughly half of the gun production machinery and trained gunsmiths went there. Remarkably, the old Qinghua Tool Factory cover name went as well, although by 1979 it probably wasn’t fooling anybody.

The relocation was a failure. The “new” Factory #626 in Xuchang never got up to speed and some of the factory never even opened. It was renamed “Firearm Development Unit #126” and shut down altogether in 2005.

Meanwhile the original Factory #626 continued on in Bei’an, now in truncated form. Previously a hallmark of quality, at least by Cold War Chinese standards, it took its first blemish with the “lost-” or “first attempt-Type 59”, China’s first try at reverse-engineering the Cold War-era Soviet Makarov pistol. The ones produced at Factory #626 were unsafe, and the PLA eventually recalled them all from service following serious injuries to soldiers.

(Model 59s were imported into the USA during the 1980s.)

Factory #626 would rectify the Type 59 problems and re-release it as the Model 59 for civilian sale through Norinco. These are identified by a single star on the grip; the unsafe “lost” version having a 1+4 stars motif. Model 59s were considered mediocre quality in the USA’s civilian market. The “second attempt” Type 59s accepted into the Chinese military were made elsewhere.

Another setback came in 1980. During the competition for a new assault rifle, Factory #626’s offering lost to Chongqing Iron & Steel’s Type 81. In the competition’s second round (jobflow for Type 81 production), Factory #626’s submission also lost.

As part of the PRC’s 1980s “socialist state market theory”, Factory #626 was semi-privatized as part of Capital Iron & Steel Corporation, who in turn spun it off as Shougang Kingho Plant.

Shougang Kingho Plant was, by the 1980s, no longer a premiere firearms factory, with aged equipment and some of its buildings dating back to 1950. Meanwhile it struggled with “capitalist concepts” like banking credit, GAAP accounting, and marketing.

The factory’s last items were unprofitable four-wheelers and poultry farming equipment. In 2006 it declared bankruptcy and permanently closed. It had made 9,006,116 guns over 55 years; many of them cloned WWII types. During 2012 a museum dedicated to Factory #626 opened in Bei’an.

That is some serious research. An excellent piece of writing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

Congratulations on having this article credited on the forgotten weapons type 50 video. Very well done!

LikeLiked by 1 person