The USSR’s M-XV class of small submarines was designed before WWII, were built and served during the war before being put out of production, and then quite remarkably were put back into production after WWII; only to leave service very soon after.

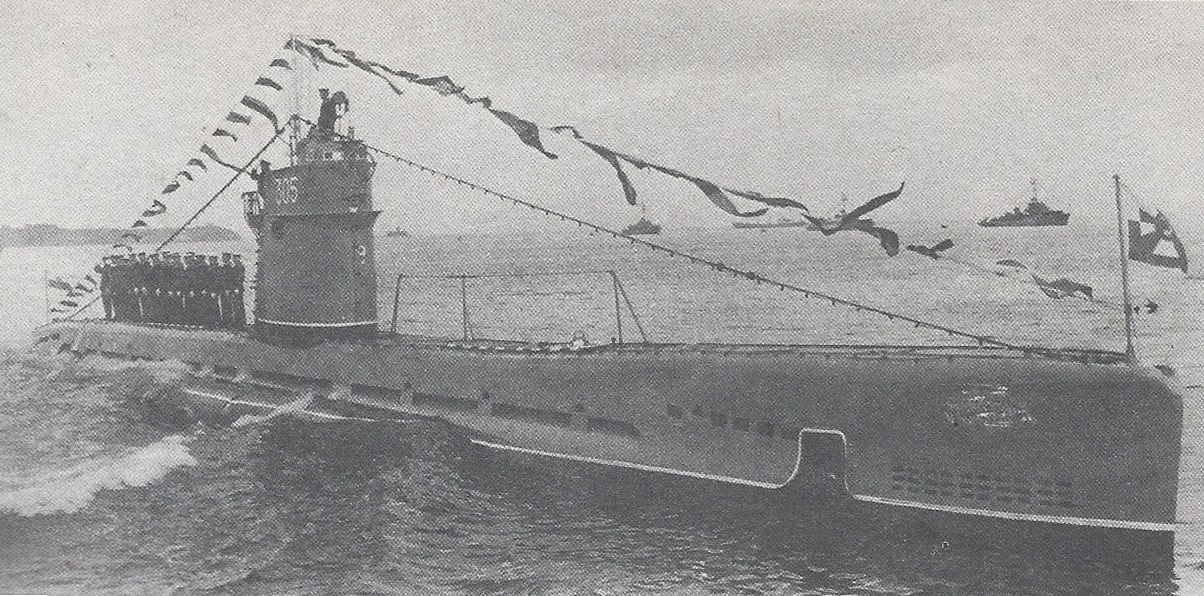

(M-294 of the Soviet navy at sea.)

Despite being almost totally forgotten today these WWII submarines served long into the Cold War era, in some cases into the 1970s, and were helpful to several navies looking to establish a modern submarine force.

(S10 was Egypt’s first submarine ever. It was formerly the Soviet M-271.)

the Malyutkas

The M-series was a family of four related designs. The whole M-series, all four variants, were nicknamed Malyutka (baby in Russian) by Soviet submariners due to their small size and as a play on their alphabetic prefix.

The earliest variant was the M-VI which was designed in only four months during 1932. The first commissioned in April 1934. One aspect was use of premade modules from inland factories transported to coastal shipyards for assembly. These were the first Soviet submarines to utilize welding for the majority of joints.

(A submarine of the M-VI, the original design, before WWII.)

These were very small submarines displacing only 197t submerged. They had just two torpedo tubes with no reloads. The maximum speed was 11 kts surfaced and 6¼ kts submerged; at that they could only travel 5 miles before the battery was depleted.

The family proceeded onto the M-VI-bis class for the 31st to 51st hulls, then in 1940 to the improved M-XII version of which 46 were built during WWII.

(M-120 was a M-XII which survived WWII. This 1947 photo shows deck gun target practice against the ex-U-18, a WWII German u-boat.)

The first three M-series variants saw some successes during WWII but also took heavy losses. Some lingered on for a while in the postwar Soviet navy.

origin of the M-XV

During January 1939, the Soviet navy looked at two proposals for how the basic M concept might be improved. One was a design, the M-II, which had previously been rejected. The other was a new enlarged, twin-engined proposal with four torpedoes. Called M-XV, it was selected by the TsKB-18 design bureau.

During August 1939, scale models of the hull and wooden mockups of internal compartments were made. Work on long-leadtime items for the class’s leadship M-200 commenced on 31 March 1940.

design

The M-XV differed significantly from the first three members of the M-series; so much so that if it had not been for the USSR’s defense bureaucracy it would have probably just been an altogether new class.

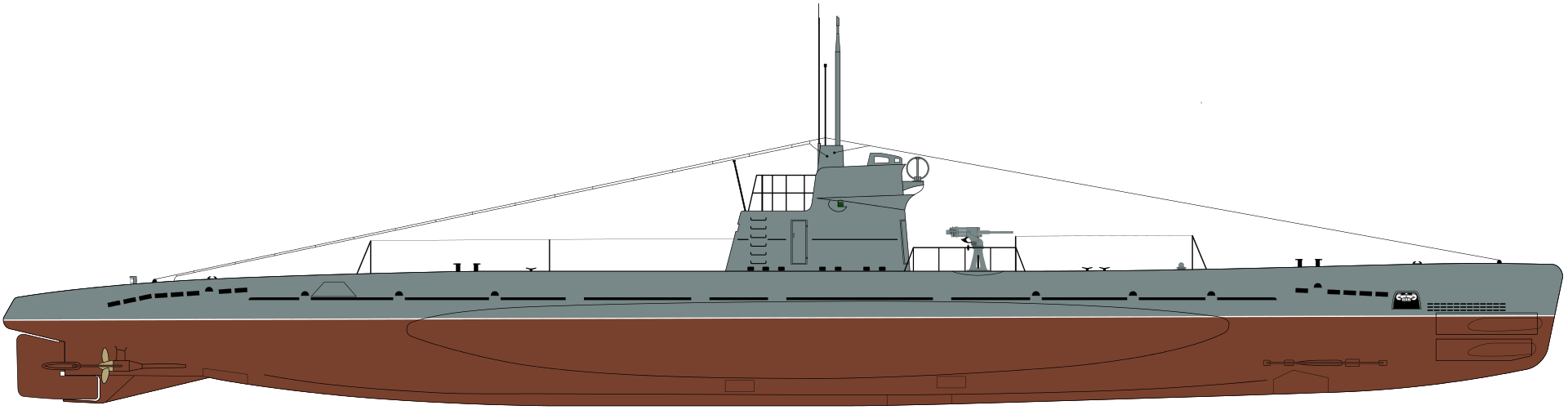

The M-XV was what the Soviets called a “hull-and-a-half” design, compared to the single-hull earlier M-series types. The pressure hull partially sat inside a sheet metal outer casing which allowed housing of some components externally. Of the five ballast tanks, numbers 2, 3, and 4 were all now external in a “side-saddle” on either side.

Internally there were six watertight compartments. The crew was 32 men, 4 officers and 28 enlisted.

The small M-XV measured 162’4″ x 14’5″ x 9’3″. The displacement was 280t surfaced, 350t submerged. Compared to their immediate predecessor, the M-XII, the M-XV was 11% longer and 37% more displacement. Compared to the original concept of 1932 the differences were 34% and 77% respectively.

The M-XV had four torpedo tubes compared to two on the earlier M-series. There were still no reloads.

The major change was the propulsion system which was completely different than the single-shaft earlier types. Both shafts had a three-bladed propeller with the single rudder between them and the stern diving planes behind them. A new 6-cylinder diesel engine, the 600hp 11-D, was used. For underwater movement a new electric motor was developed, the PG-17, and one was mounted on each shaft. The batteries were a new type, a 60-cell lead-acid design of which there were two. The onboard pumps were TP-18s which were stronger and more reliable than earlier little models. The HP compressed air capacity rose to 76 ft³.

The maximum surfaced speed was 15½ kts. The maximum submerged speed was 7.9 kts. Like most WWII submarines, underwater endurance on the batteries was poor. A M-XV could travel 85 NM at a 2¾ kts creep, the minimum speed needed to move water over the control surfaces. At 7¾ kts the range fell to just 10 NM.

The safe diving depth was only 197′ with an absolute limit of 235′. Even by WWII standards this was modest.

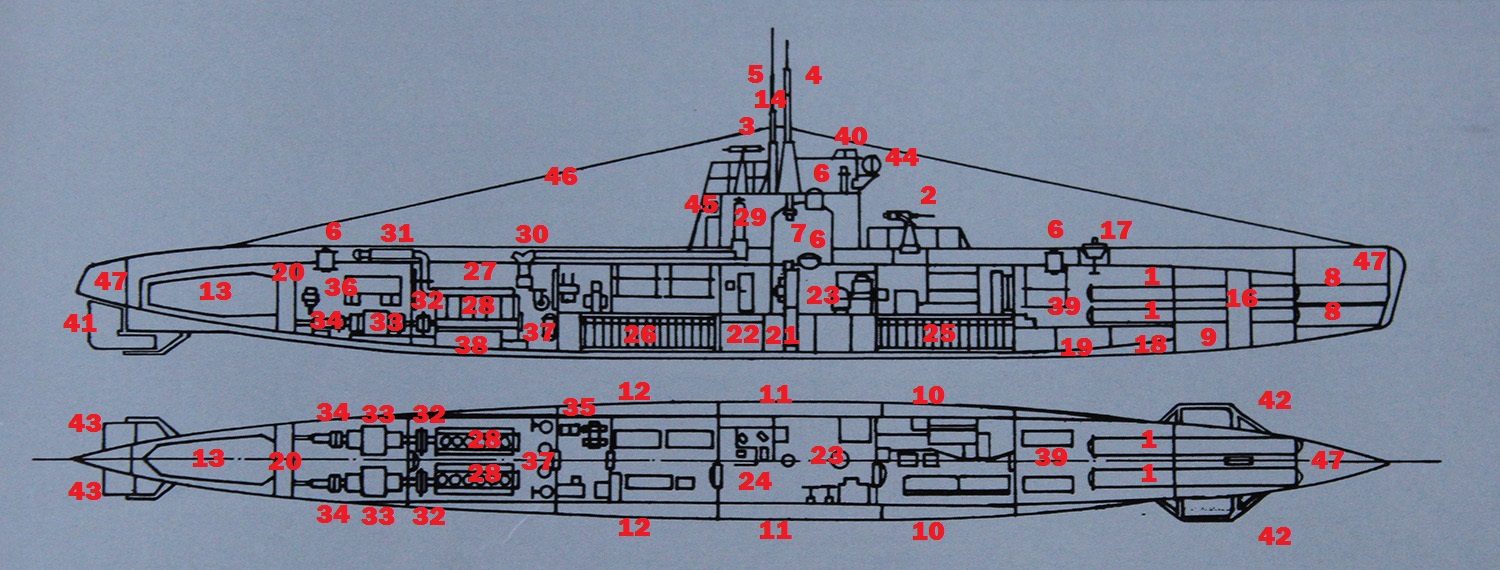

(Basic schematic: 1) torpedo tubes 2) 21-K deck gun 3) AA gun mount 4) #1 periscope 5) radio antenna 6) hatch 7) emergency escape lockout 8) tube muzzle shutters 9) #1 main ballast tank 10) #2 main ballast tank 11) #3 main ballast tank 12) #4 main ballast tank 13) #5 main ballast tank 15) #2 periscope 16) anchor chain locker 17) distress buoy 18) aux tank 19) forward trim tank 20) aft trim tank 21) “crash” tank 22) “surge” tank 23) compass 24) control room 25) forward battery 26) aft battery 27) machinery room 28) 11-D diesel engine 29) air intake sump 30) air manifold 31) exhaust muffler 32) clutch 33) PG-17 electric motor 34) Michell bearing 35) HP air compressor 36) TP-18 pump 37) oil pumps 38) oil tanks 39) bunkroom 40) bridge 41) rudder 42) bow planes 43) stern planes 44) RDF loop 45) navigation light 46) livewire radio antenna 47) free-flood voids)

There were two small special ballast tanks. One was designed to flood nearly instantaneously, to help drag the submarine down if it needed to crash dive. The other surged ballast to compensate for the rapid weight shift if all four torpedoes were fired rapidly.

The crew accommodations were harsh and the M-XV class could only stay at sea for a maximum of 26 days; usually 1½ weeks was considered the limit. Despite the hardships, WWII Soviet submariners liked this design as they felt it was uncomplicated and safe.

There was no snorkel. To run on diesels or charge batteries, the submarine had to be surfaced. Air was taken in through the floor of the AA gun balcony.

One thing carried over from the original concept was modular construction. These submarines were sized so that subassemblies could move on railroad flatbed cars and be quickly welded together at a shipyard.

(Modular construction of M-XV class submarines.)

during WWII

The Soviets planned big for this class of small submarines; six dozen at a minimum and maybe as many as one hundred. The USSR re-entered WWII on 22 June 1941 with the German invasion. At that time, subassembly modules for the first seven hulls had already been delivered to Leningrad. These were hastily evacuated out of the city during the summer of 1941.

Taken to Astrakhan in southern Russia, the first four were then further evacuated to Baku (today in Azerbaijan) when the Germans looked poised to take Stalingrad and cross the Volga. These four were completed in Caspian Sea shipyards.

(M-203 was the last of the four completed during WWII.) (photo via deepstorm.ru website)

The leadship M-200 was probably the most active during WWII. Homeported at Polyarny near Murmansk in the Russian arctic, M-200 operated as far away as Norway and sank several minor German ships.

All four commissioned during WWII survived the conflict.

after WWII

As mentioned above the four commissioned during WWII survived the war. Of the other three which had been started, they were left unfinished during WWII but with already-completed subassemblies warehoused. These three, M-204, M-205, and M-206, were finally completed in 1947.

There were three more started quickly after the 1941 German invasion, but abandoned early in construction and either scrapped or destroyed during WWII. Another 18 were cancelled in 1941 before construction began.

Another seven ordered during 1941 had some subassemblies completed but were put on hold when the M-XV project’s workflow and job order specialists were reassigned to maximize production of T-34 tanks. The stored items were regathered in 1945 with these seven commissioning between 1947 – 1948.

| proj. | comp. | total | |

| Commissioned during WWII | 4 | ||

| Started during WWII, construction abandoned | 3 | ||

| Cancelled during WWII | 18 | ||

| Started during WWII, but completed and commissioned after WWII | 10 | ||

| Started, completed, and commissioned after WWII | 43 | ||

| Started after WWII, never completed | 1 | ||

| (totals) | 22 | 57 | 79 |

postwar restart

By the late 1940s, the M-XV design would seem to be an unlikely candidate for fresh production orders. These small submarines were designed to fight at a 1930s technology level and were by now totally obsolete.

At the same time, the USSR acquired German u-boats of numerous classes at the end of WWII, with all their inherent technology which was far in advance of anything in the Soviet Union at that time.

(The large Type XXI was the most advanced German u-boat class. They came too little, too late to help Germany during WWII. U-3041 commissioned two months before Germany surrendered and was one of four Type XXIs the USSR received after WWII. It was renamed B-30. It is shown here during the 1950s at Liepāja, which is discussed more later.) (photo via deepstorm.ru website)

The big, fast Type XXIs were streamlined and intended to operate almost exclusively submerged.

(The small Type XXIII likewise came too little, too late to help the Kriegsmarine much. U-2353 was the only intact Type XXIII which the Soviets got after WWII. As N-31, it served the Soviet navy until March 1952. N-31 was homeported at Ust-Dvinsk which today is Daugavgrīva, Latvia.) (photo via deepstorm.ru website)

At the other end of the size spectrum, the WWII German Type XXIII was actually smaller than a M-XV but infinitely more capable. Fitted with a snorkel, the Type XXIII could stay submerged for extended periods. It was equipped with a Anlage sonar system. It was faster submerged than surfaced and at 4¼ kts could travel 170 NM without snorkeling. These were extremely quiet underwater and no sonar in the Soviet fleet at the time could even find N-31 during exercises.

With all this, it would seem quite odd to restart production of an obsolete design lacking both oceanic range and advanced German technology. But in January 1947, that is indeed what happened with the M-XV. There were several factors.

The first was political. When WWII ended in 1945, Josef Stalin bizarrely ordered the restart of several prewar naval construction efforts, against the advice of his admirals. This ran up the gamut of types, even including Sovetsky Soyuz, a battleship started at Leningrad in January 1939 and 19% complete after WWII. Efforts to resume work on this obsolete design sputtered along for three years after WWII before Stalin allowed it to be broken up. Some of these rash decisions were tempered down by a 10-year naval plan Stalin finally agreed to, others were not.

(The light cruiser Chkalov was started in August 1939. Work was suspended in 1941 and did not resume until 1946. Chkalov commissioned in 1950, instantly obsolete.)

For Stalin, the M-XV submarines were doubly-attractive as the modular construction technique freed up shipyards for other designs.

(Seen here in later Polish service as ORP Krakowiak, M-236 was the first M-XV both started and finished after WWII had ended. Work began during February 1947 and M-236 commissioned in October 1948.)

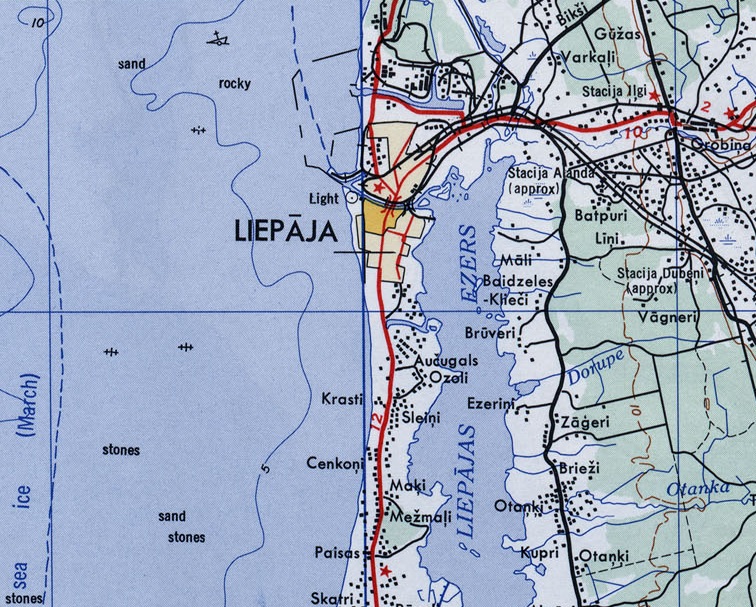

On a more practical level the Soviet navy still saw a niche for small, coastal submarines after WWII. Particularly in the Baltic Sea, which was now a focal point vis-a-vis the western former Allies of WWII, these types had wider options than deep-draught submarines suitable for the open Atlantic. Geopolitical changes of 1945 also came into play: in the Baltic the USSR annexed the upper half of East Prussia and Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. New Baltic naval bases which were ice-free most of the year were acquired: Kaliningrad (the renamed Königsberg), Baltiysk (the renamed Pillau), Paldiski, and Liepāja among others.

Liepāja (today in Latvia) in particular was a useful acquisition. During WWII the German navy (which called the city Libau) had piers for u-boats, a torpedo overhaul depot, a seaplane ramp, and other facilities. The 25th U-boat Flotilla was based in the city between 1942 – 1944.

Liepāja was an ideal home for Baltic Fleet M-XVs after WWII due to the pre-existing submarine infrastructure.

(A 1954 US Army map of the area. The submarine base was located in the north, at the ⊥-shaped channel.)

(A 1954 US Army map of the area. The submarine base was located in the north, at the ⊥-shaped channel.)

(Two M-XV class submarines at Liepāja during the 1950s.)

Liepāja was made a closed military city, with Soviet citizens needing a special pass to visit. The northern neighborhood was a secondary restricted area where even city residents needed a pass. The commercial port in the city’s downtown was wound down during the 1950s and from 1961 onwards, closed to foreign-flagged merchant ships. At times the whole area was closed to any civilian shipping.

(The structure to the left was a rangefinder for a Soviet coastal defense battery at Liepāja . The right tower is a WWII German observation post.)

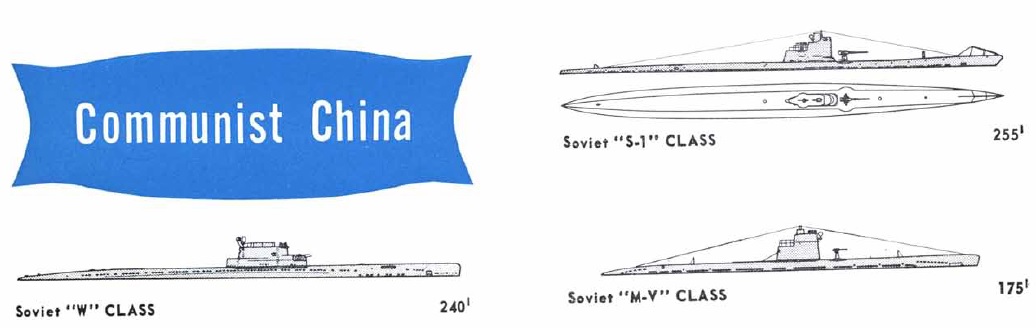

(Declassified in 2007, this 1954 CIA memo makes mention of M-XV submarines at Liepāja.)

Elsewhere, with the annexation of Moldova and Romania and Bulgaria becoming communist satellite states, the Black Sea was now “a Soviet lake” where lower-technology warships might face off against Turkey.

Meanwhile the small size of the M-XV allowed for an interesting way of beefing up the Soviet Pacific Fleet’s submarine force: with some disassembly, M-XVs could be moved clear across Asia via the Trans-Siberian Railway and then reassembled at Vladivostok.

With all these factors, post-WWII construction of M-XV submarines resumed in February 1947.

POST-WWII SERVICE

USSR

In 1947 the Soviet navy felt that this design might still have some currency in restricted, shallow waters such as the Baltic Sea.

The small size and shallow draught of the M-XV design gave these submarines surprising inland mobility. After the Volga-Don Shipping Canal opened in 1952, these submarines could self-navigate between the Caspian and Black seas. They could self-navigate 200 miles up the Volga river and a similar distance up the Amur river in the Russian far east, and by using inland waterways during summer, transfer between the Northern and Baltic fleets without going around Scandinavia.

(M-240 far from any ocean, in the capital Moscow.)

The biggest handicap is obvious: by the 1950s these submarines were obsolete in every way.

The M-XV was designed without radar and none ever received it. It was also designed without sonar, and only some completed after WWII had a simple Mars system, which was more just a microphone outside the hull than any tactically-usable sonar.

Up until the late-war German types, all WWII submarines were noisy. Hydroacoustics were not well-understood during the 1930s and early 1940s, and in any case the biggest threat was thought to be short-range active “pingers”. As sonar technology advanced, passive (listening) offered longer ranges and became the primary threat, with sound silencing now important after WWII.

One unavoidable source of underwater sound in WWII submarines was flow noise, the byproduct of hydrodynamic drag. Before WWII a submarine was basically a surface warship able to submerge for short periods, and as such, was designed primarily as a surface warship. There were a huge number of protrusions: railings, the deck gun, masts, lifelines, bollards, deckplates, and so on which created flow noise underwater.

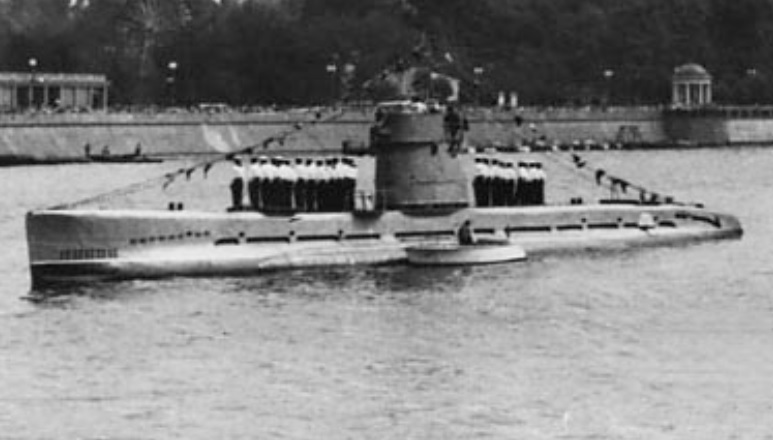

(drawing via russianships.info website)

Cold War-era submarines had resilient mountings; for example on any pump, electric motor, gearbox, etc there is a “break”, be it springs or rubber, between the equipment and the deck or hull. Like almost all WWII submarines, the M-XV lacked this and any machinery noise vibrated directly onto the hull and then into the sea. Some upgraded WWII submarines, like the US Navy’s GUPPY program, attempted to address this however much the WWII design allowed, but with the M-XV there simply would not have been any room.

Cavitation is a moving object in water creating tiny bubbles which then pop under sea pressure. It is a major type of submarine noise. The two long-chord 3-bladed propellers caused a lot of cavitation, which was exacerbated by twin-wing “bumpers” that protected the delicate trailing edges of the M-XV‘s stern planes.

During 1952 M-247 was fitted with reduced-cavitation propellers however they were intended for future classes, not for refit to the remaining M-XVs.

(M-283 being scrapped during 1961. This shows the long-chord, high-cavitation propellers and the “bumpers”. The chute-like thing was a sheet metal housing to direct diesel exhaust downwards when surfaced. Underwater, it created a vortex and was one of many flow noise sources.) (photo via deepstorm.ru website)

The M-XV used Type 53-38 torpedoes, which was the USSR’s standard type during WWII. These had been designed during the mid-1930s.

(Type 53-38 torpedo.) (photo via navweaps website)

This was a basic unguided, straight running anti-surface torpedo with an impact fuze. It had three speed settings between 30 – 44½ kts with corresponding ranges between 5¼ NM to 2 NM. The 53-38U modification added a magnetic fuze but the weapon was still a straight-runner. The USSR was not alone in using WWII torpedoes well into the Cold War; the US Navy still had WWII Mk14s on hand in 1969. By then these were usually only used to round out a torpedo room’s capacity alongside new designs. For the M-XV class however, there was no chance of moving on to guided types as these submarines had no fire control equipment.

The four torpedoes could only be loaded in port. The M-XV was trimmed aft-down to the maximum degree possible and then the torpedo was craned onto a special raft which slid it into the tube through the muzzle.

The anti-aircraft gun feature on the M-XV was already useless when WWII was still in progress. It was just a pintle for an infantry light machine gun. It should be remembered that the M-XV was designed when biplanes were still in use. The balcony was so small that two men could barely stand on it at the same time. The machine gun was not submersible and had to be installed and stowed each surface cycle. By the early 1950s many M-XVs already had the pintle removed.

The deck gun was a 21-K. It fired a 45mm round with a 4¾ lbs shell. It was visually-aimed, hand-loaded, and manually operated. A M-XV carried 200rds.

(21-K deck gun on the Egyptian S10, formerly the Soviet M-271. Unrelated to the gun, the object on the front on the conning tower is a RDF loop which revealed the direction of a radio transmission.)

The era of the deck gun ended with the end of WWII, if not already before. By 1945 there was no chance of a gun this crude and little having any battle effect, and in any case, it would be suicidal for a submarine to stay surfaced against modern post-WWII ASW warships or aircraft. During 1957 the Soviet navy issued a directive to remove deck guns from all M-XVs still in service.

Beyond all these things, time had simply passed the design by. Submarines of the late 1940s and early 1950s had snorkels and stayed underwater almost exclusively. For the M-XV this was impossible; it had no snorkel and the meager battery capacity meant that it would have to recharge frequently. The austere living conditions and warload of just four torpedoes further limited their effectiveness.

During 1951 the Rubin design bureau proposed a design update with sonar and other modest improvements. By then the Soviet navy had already lost interest in the M-XV and it was not acted on.

Other nations built “small submarines” after WWII. The difference was that they incorporated postwar technology and were made for a niche role: for example Sweden, to its area of the Baltic or Yugoslavia, to the Adriatic sea. Italy’s Enrico Toti class appeared three years after the last M-XV left the Soviet fleet and was of similar size. However it had a snorkel, sonar, radar, wire-guided torpedoes with reloads, and modern batteries.

anechoic coating trials

M-283 was involved in the earliest Soviet research into anechoic submarine coatings.

During WWII both Japan and Germany experimented with “anti-sonar coatings” on submarines, with the German effort being more advanced. It was codenamed “Alberich”. This was 4mm-thick panels 10’9″² in area affixed to the outside of a u-boat. The panels were a polyisobutylene named Oppanol, perforated with holes of two sizes. The goal was to “deaden” the return “ping” of British active sonars. “Alberich” worked to the extent that it cut up to 15% off the range of Allied sonars however it took over a thousand man-hours to do one u-boat, the coating added hydrodynamic drag, and it often fell off at sea.

During the Korean War era the USSR sought to restart this technology field. After experiments with synthetic rubber on an earlier Malyutka (Chelyabinsk Komsomolets, a M-XII which survived WWII) M-283 was selected for full trials of a Soviet equivalent to “Alberich” during May 1953.

The trials aboard M-283 ran from 1953 – 1956. The Soviets tried applique-like broad sheeting, smaller sections of paneling, and tiles. The biggest challenge was keeping the material lightweight enough to not affect the submarine’s performance, but also sufficiently thick to work. Like the Germans, the Soviets encountered problems with keeping the coating attached.

Against active (“pinging”) sonar, the results were similar to what the Germans found during WWII. A surprise was that against passive (“listening”) sonar, the coating was much more effective, as it kept noise of M-283‘s own machinery trapped within the submarine, on an order of 50%+.

The coating aboard M-283 was removed in 1956; of note the shipyard work order stated “remove remnants of….” which may indicate that there were still problems with the glue. Overall the idea was a success and the first operational submarine with it was the second “Victor-I” atomic-powered attack submarine, K-69, which commissioned in 1968.

tragedies

Within Russia, unfortunately this class is usually only remembered for two negative events.

loss of M-200

On 21 November 1956, M-200 (the class leadship) was surfaced in the Baltic Sea with the destroyer Statny. Earlier in the day, M-200‘s captain had admonished his destroyer counterpart that the little M-XV had a lot less speed and maneuverability than the powerful destroyer. At 19:53 Statny rammed M-200, quickly sinking it. Six crewmen were killed directly by the collision. Another eight exited M-200 before it sank, of whom two drowned due to inefficient rescue efforts. The remaining crew was trapped in the forward compartment of M-200, which settled on an even keel on the seafloor.

An alert was sounded seven minutes later at Tallinn naval base but from then on, efforts to rescue the trapped men unraveled. At 28:05, M-200‘s distress buoy was located. This marked the submarine’s position and allowed telephone communication with the survivors. By then, some of the 28 men who had initially survived had already passed away.

During the overnight of 21 – 22 November, a good amount of time was wasted bickering over who was in charge of the rescue, and then a questionable plan to slide cables underneath M-200, drag it to shallower water, and then have the submariners free-ascend there, as opposed to doing that right away. This plan was aborted at the last moment, with all the hours being wasted. Since 04:00 the trapped men reported that they were ready to free-ascend, but were ordered not to.

During 22 November, a fresh air hose could have been attached to M-200‘s outboard pneumatic valve, but apparently nobody in the rescue flotilla was familiar with the design.

During the early evening of 22 November, a new plan was created, to have heavy-lift ships directly crane the flooded small submarine up to the surface. This was supposed to start at 18:00 however the weather worsened and the rescue flotilla was scattered by rough seas. M-200‘s distress buoy’s cable was snapped by the waves, preventing further communication. Nobody in the flotilla had accurately annotated its last position, resulting in more time lost trying to find M-200, which by now was almost certainly running out of air.

At 03:47 on 23 November, the submarine was found again and divers were sent down. All of the crewmen were by then asphyxiated. One man, a midshipman, was in the lockout trunk in an ascent hood. It appears that on 22 November the survivors decided to ignore orders and just go; with the midshipman being the first. The M-XV lockout was such that, once started, it had to be either finished or reversed from the inside. An autopsy of the midshipman revealed that while mid-procedure, he had cardiac arrest combined with CO² poisoning. When he passed away inside the lockout, he inadvertently doomed the others.

Overall the M-200 loss was a showcase of ineptitude at all levels. The captain of Statny was sentenced at court martial to three years hard labor. Little else was done. M-200 was raised later in November and scrapped.

(M-200 attached to the salvage pontoon which raised it. The circular hole in the weather deck housed the deployed distress buoy.) (photo via deepstorm.ru website)

(Monument to M-200 in Paldiski, Estonia.) (photo via flot.com website)

loss of M-252

On 18 September 1959, the Pacific Fleet’s M-252 was patrolling in the Sea Of Japan. A typhoon had previously been detected but word was not passed to M-252. As the seas picked up, the captain headed for home however the port side Michell bearing (a device which prevented stresses on the propeller end or engine end from traveling up or down the shaft) broke. M-252 had gone to sea without a spare for one simple reason: the Soviet navy ran out of them and with interest in the M-XV class waning, chose not to restart spare parts production.

With only ½ power now available, M-252 was overcome by rough weather and smashed against coastal rocks with the hull being breached. The captain ordered the crew to abandon ship and swim to shore however four did not make it.

The abandoned M-252 was recovered after the storm and scrapped.

At court martial, M-252‘s captain was acquitted of any wrongdoing. However no further legal cases resulted. Further inquiries would have exposed ashore commanders in the Pacific Fleet’s meteorology and supply departments, and the Soviets apparently just chose to move on. During the court martial, it was revealed that M-252‘s squadron had requested the obsolete submarine be decommissioned a month before the incident but this had been denied. This was the second accident of a Pacific Fleet M-XV in 15 months; previously M-281 almost sank (it was on the seafloor for 40 minutes) due to flooding and a ballasting problem.

end of Soviet service

By the mid-1950s, Stalin was gone and the decision to restart production of these obsolete submarines after WWII was acknowledged to have been a mistake. M-294 was the last one built, commissioning on 26 February 1953. One additional hull was never finished and used as an oil storage pontoon.

(M-294, the last M-XV built, only had a 7½ years career.)

The short timespan between new M-XVs being built, and then being totally gone, is astonishing. Less than three years after the M-XV was still in production, the USSR was already getting rid of them. M-201, a Baltic Fleet unit and one of the four to have seen WWII combat, decommissioned on 29 December 1955.

M-294, M-285, and M-293 participated in a large Pacific Fleet wargame during the summer of 1958. This would be the final time the M-XV class would factor into major training exercises in the Soviet navy.

The Baltic Fleet discarded more during 1958, and on 6 February 1960 decommissioned the remaining six still under its command.

The Black Sea Fleet starting decommissioning M-XVs during January 1958. On 22 November 1960, M-237 and M-247 decommissioned together for conversion into a PZS. They were the last M-XVs in the Black Sea Fleet.

(Pacific Fleet M-XVs at Nadhodka during the 1950s. The Pacific Fleet was the last of the USSR’s four fleets to use this design.) (photo via fleetphoto.ru website)

On 22 November 1960, the Pacific Fleet decommissioned a half dozen of its M-XVs. Another seven went in a mass culling on 4 April 1962. Now only M-292 remained, the last M-XV still in frontline service in any Soviet fleet. It was decommissioned on 7 May 1963.

PZS conversions

A PZS was an obsolete submarine converted into an immobilized pierside battery-charger. A submarine at rest still needs electricity for things like fans, lighting, the galley, etc. One way to do this is to start the diesels and do battery recharges; however this adds pointless wear & tear on the submarine’s engines. Another way is to use an outboard source. A PZS had only a partial crew and was no longer capable of going to sea. By using a voltage distributor, cables could carry a full electrical load to several nearby submarines simultaneously. A PZS was used until its own diesel engines wore out, and then scrapped.

The Soviets were not alone in doing this; for example the Turkish navy used ex-American WWII submarines for battery charging.

(PZS-6 was the new name for M-247 between December 1960 – March 1963. Here it is recharging a “Quebec” class submarine of the Black Sea Fleet.) (photo via deepstorm.ru website)

PZS-2, formerly M-272, was the last in use for this role. It was discarded on 12 August 1970. With that, the M-XV was totally gone from the Soviet navy.

DOSAAF M-XVs

In the Soviet Union, DOSAAF was a government-run patriotic organization to exhibit functional military gear to the general public. Normally submarines were not featured but the ability of the M-XV class to access cities via inland waterways, combined with their total technological obsolescence, resulted in several being donated to DOSAAF after they were discarded by the Soviet navy.

(M-243 was used by the DOSAAF chapter in Astrakhan during the 1960s. It had been PZS-26 for a year before its diesels started having problems.)

(M-240 was a DOSAAF unit in Moscow during the 1960s. This 1976 photo shows it derelict. It was scrapped during 1981.)

DOSAAF gear was used until it became unsafe or unpresentable to the public, and then discarded.

Cold War-era follow-on

Even while M-XVs were in their restarted production run, the USSR was working on a successor Malyutka. This would be the Project 615 class, known to NATO as “Quebec”. These were somewhat larger and also featured a third engine which could run off LOX while submerged. Construction began in 1952 and the Soviets planned 100 of these.

The “Quebec” class had significant safety concerns and the project was cancelled after the 30th was built.

Thereafter, Soviet diesel-electric submarines split down two technology trees: medium-endurance classes: the “Whiskey”, “Romeo”, and very advanced “Kilo”; and fleet boats: the “Zulu”, “Juliett”, “Foxtrot”, and “Tango” classes. There would be no more Malyutkas, time had passed the WWII concept by.

exports

BULGARIA

Bulgaria did not operate submarines during WWII. The 1947 treaty which legally concluded WWII between Bulgaria and the Allies had in its 13th clause, a prohibition on Bulgaria possessing submarines going forward.

With Bulgaria established as a communist satellite, the USSR secretely began preparing the nation to operate submarines. During 1952, a group of Bulgarian sailors was sent to Odessa in the USSR to begin training. They wore Soviet uniforms and even within the Soviet navy, this was a secret. M-204, a Black Sea fleet M-XV, was used for this.

During the summer of 1953 M-204 was discretely turned over to Bulgaria however still kept within the USSR. It carried a fictitious Soviet pennant number “362” on the conning tower. Later that year, Bulgaria repudiated the naval restrictions of the 1947 treaty.

On 18 August 1954, the USSR formally transferred three M-XVs to Bulgaria. None received new Bulgarian names and were known just by the pennant numbers on their conning tower: M-202 became “41”, M-203 became “42”, and M-204, which was already Bulgarian-crewed, became “43”. Their homeport in Bulgaria was Varna.

Bulgaria viewed the M-XV as an insufficient, stop-gap type only and they were only used to train future submarine crews.

After only four years, all three decommissioned. M-202 and M-203 were returned to the USSR in late 1958 and scrapped. M-204 was kept at Varna and consideration was given to mothballing it. However during 1959 it was scrapped in Bulgaria. One of its periscopes survives today in a Bulgarian museum.

The M-XV was successful in preparing Bulgaria for the Cold War-era “Whiskey” and “Romeo” class submarines the USSR provided next.

CHINA

After Mao’s 1950 victory in the Chinese civil war, the PLAN (People’s Liberation Army – Navy) expressed a desire for submarines. The USSR transferred a number of obsolete WWII types out of the Pacific Fleet, among them four M-XVs.

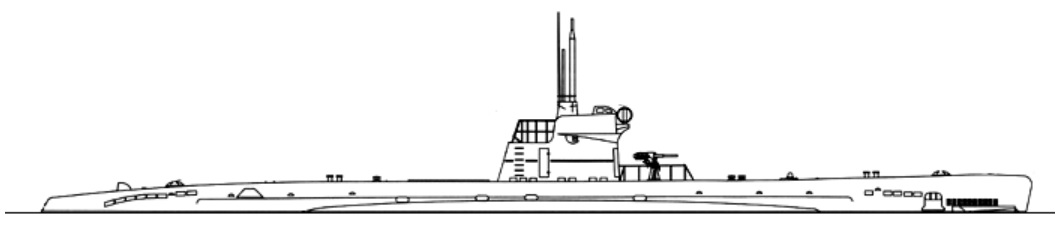

(Excerpt from an old US Navy Submarine Recognition Manual, showing the PLAN’s first submarines: a WWII Stalinets IX-bis (mislabeled “S-1”), a Cold War-era “Whiskey”, and a WWII M-XV (mislabeled “M-V”). Missing is the WWII Shchuka class; perhaps naval intelligence was unaware that China had some.)

During the autumn of 1954 the USSR agreed to give China four M-XVs. The ships selected, and their new names, were M-276 (Guofang 200), M-277 (Guofang 201), M-278 (Guofang 202), and M-279 (Guofang 203). The Chinese name means “national defense” in Mandarin. All four were handed over at Qingdao, China; two in 1954 and two in 1955.

Next to nothing is known about the careers of these four submarines in China. They served past the Sino-Soviet Split in 1961. One decommissioned in 1963 which may indicate a potential accident or problem. The others were discarded in 1968, 1969, and 1970.

POLAND

The Polish navy operated submarines before, during, and after WWII. Unlike the other M-XV export recipients, Poland had no need for them as an “introductory type” and instead used them as frontline units.

(ORP Sep was a WWII Orzel-class submarine which served on until 1969, alongside the M-XVs and even some Cold War-era designs.)

The USSR viewed Poland as a key Cold War ally and offered a half-dozen M-XVs. The ships and new names were M-270 (ORP Podhalanin, later ORP Slazak), M-290 (ORP Kaszub), M-246 (ORP Kurp, later ORP Mazowsze), M-236 (ORP Krakowiak), M-245 (ORP Kujawiak), and M-274 (ORP Mazur). The submarines were handed over during 1954 – 1955 at Gdynia, Poland.

(ORP Kujawiak in Polish service. Like the Soviets, the Poles deleted the useless deck guns.)

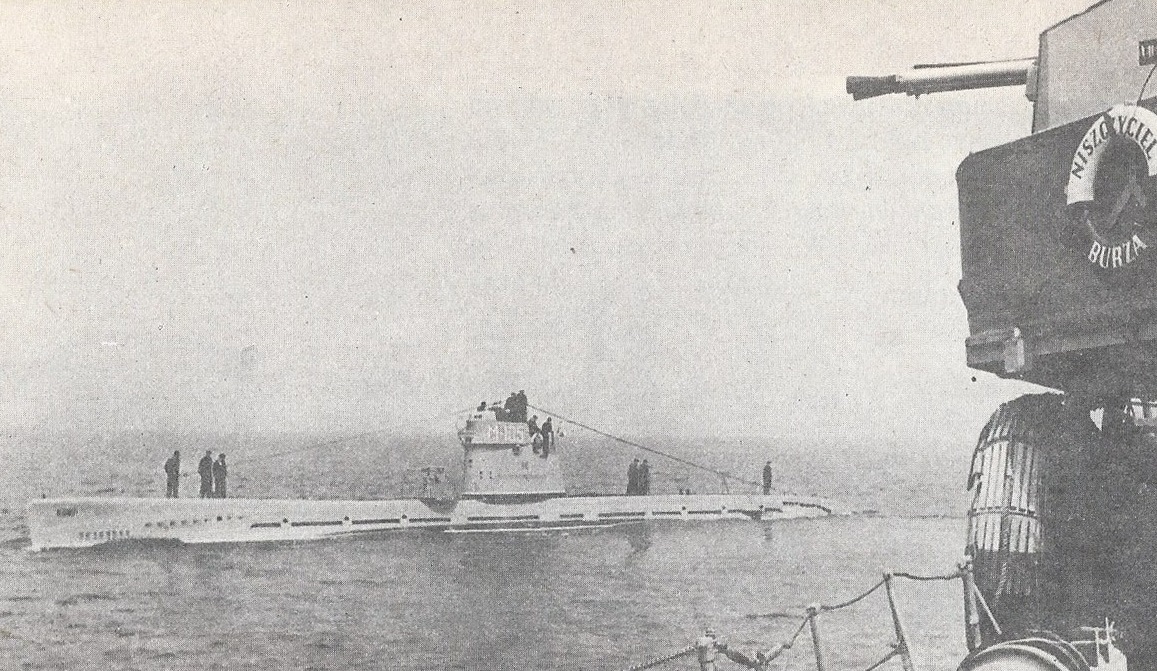

(ORP Mazur at sea.)

Despite being obsolete Poland considered these small submarines still highly viable for their likely combat zones in the event of a war with NATO, those being the Baltic’s belts and the Danish Kattegat.

(ORP Kurp at sea before the deck gun was removed. ORP Burza was a WWII Wicher-class destroyer which served on until June 1960.)

During 1957 ORP Mazosze, ORP Krakowiak, and ORP Kujawiak made an ambitious joint patrol in the North Sea opposite the British Isles, a distant destination for submarines this small.

There was one accident in Polish service. On 28 November 1957 ORP Kaszub was caught in a storm and pushed aground off the Vistula Spit, the very thin stretch of land where Poland’s coastline meets Russia’s. Three sailors lost their lives. The captain tried to free the submarine but high waves pushed it all the way onto the beach. ORP Kaszub was later ungrounded and repaired in Poland.

There was no wrongdoing in this case, it was more a matter of the inherent danger in operating such a small warship with limited engine power.

Poland began to discard these submarines as the Soviets made later Cold War-era designs available for export. The first to go was ORP Kaszub on 1 February 1963. The last was ORP Kujawiak on 31 December 1966. It was sunk as a gunnery target.

ORP Slazak had decommissioned on 20 October 1965. It was then used as the Polish navy’s salvage training hulk, being repeatedly scuttled for practice salvage raisings. After it wore out, it was left on the seafloor at a depth of roughly 101′ offshore of Jastarni, Poland in the Danzig Gulf. With the end of communisim in Poland, the wreck was made an open area and is a popular scuba diving site. By 2023 the hulk is rusted and covered in barnacles.

(The bow bullnose of ex-ORP Slazak during 2014.)

EGYPT

After the 1956 Suez Crisis, an urgent plea was made to the USSR for submarines.

The Egyptians were totally lacking not only in any previous experience at sea with submarines, but also in ashore infrastructure; the majority of that being leftover from WWII and oriented towards supporting Royal Navy surface warships.

Operating submarines is a very unique thing for any navy. It could be said that a generic navy capped at frigate-sized surface warships, could more easily advance up to heavy cruisers than down to submarines. There are unique spare parts requirements, hull inspections, and drydocking skills needed.

During the winter of 1956 – 1957, Soviet military attaches in Cairo inquired if the Egyptians might be interested in the M-XV class, a simple design to start them off with. The Egyptian navy said it was, and requested two. The USSR agreed to provide one, a Baltic Fleet sub, M-271. The transfer agreement was signed in June 1957 and M-271 was delivered to Alexandria on 1 October 1957.

(S10, Egypt’s first submarine ever, in Alexandria harbor.)

Even though it was their first submarine ever, the name S10 was assigned. (Curiously the Egyptian navy restarted the sequence with a later “Whiskey” class, S1, in 1957.)

S10 was used as intended by the USSR and not only trained Egypt’s first submariners, but familarized the ashore command with the maintenance requirements. The Soviets were impressed enough that in June 1957, deliveries of the Cold War-era “Whiskey” class began, followed later by the “Romeo” class. By the early 1960s, S10 was used only for basic training of recruits destined for more modern submarines.

During the Six Day War in 1967, Egypt urgently tried to get S10 operational again but the short war ended before that could be accomplished. After the war, S10 was more or less left dormant until being scrapped in 1971.

postscript

No M-XV was preserved anywhere. Besides the aforementioned sunken ORP Slazak, two other M-XVs still exist, also on the seafloor.

After decommissioning in 1958 M-241 was used as the Soviet Black Sea Fleet’s salvage trainer, filling the same role for the USSR as ORP Slazak had for Poland. It was likewise abandoned when it could not be sunk and raised any more. During 2014 the Russian Federation navy found it off the Crimean coastline at 647′ depth, in very poor condition.

M-244 was donated to the Kiev chapter of DOSAAF in February 1960. It was moored in the Kanevsky Reservoir south of the city. Sometime during the late 1960s, the submarine (which by then was no longer used by DOSAAF) parted its moorings and sank.

As the reservoir is clean freshwater, the sunken submarine might presumably still be in good condition. It is thought that the most likely place is somewhere around a nameless islet in the reservoir about 13 miles south of Kiev. During 2009 a Ukrainian naval veterans group tried to find it, with a goal of raising it for display in Kiev. They were unsuccessful. At the start of the Russo-Ukrainian War in 2022, UXO was introduced into the reservoir so M-244 is unlikely to be found or recovered.

Overall this class is largely forgotten today.

I want to give a hat tip to the excellent website Deepstorm ( http://www.deepstorm.ru/ ) which for 20+ years has been the best resource online for information about Soviet and Russian submarines.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on .

LikeLike

This was definitely new and different. On the related note of WWII era torpedoes the British MK VIII burner cycle torpedo was in RN service from the late 1920s to the early 1990s and some may still be limited issue. The most famous post war use of the MK VIII ** was when HMS Conqueror sank the ARA General Belgrano during the Falklands War. Another interesting use of the MK VIII was the Oscarsborg Fortress’ shore torpedo battery where they replaced pre-WWI Austro-Hungarian Whitehead torpedoes.

LikeLiked by 2 people

If I recall correctly something I had read long ago, the captain of HMS Conqueror had doubts about the reliability of the more modern torpedoes and elected just to go with a straight-runner.

LikeLike

ORP Kujawiak after being removed from the fleet in 1966, was sunk in the Bay of Puck as a gunnery target. The wreck is located at a depth of 5 m, and the sail sticks out of the water. The hull is well preserved.

LikeLiked by 1 person

ORP Kujawiak

LikeLiked by 1 person

One detail about Project 615 submarines. The last boat in the series (M-361) was modified to store oxygen in solid form – sodium superoxede (NaO2). A solid crystal grains, that could be made to release oxygen by heating it by merely 100C (2 NaO2 = Na2O2 + O2), or putting it in water (2 NaO2 + 2 H2O = 2 NaOH + H2O2 + O2).

So basically this stuff allow you to run oxygen drive without all the problems of storing liquid oxygen onboard. M-361 worked perfectly on trials, but the whole air-independent propulsion concept was viewed as “outdated” by admirals, fascinated by nuclear power. So this direction was not followed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always liked the Quebec, if they had managed to iron out the safety problems I think it could have been a useful thing.

LikeLike