The last country to produce new Mosin-Nagants was perhaps the most obscure player in Cold War-era Europe, Albania. There a small run of this rifle was made in the early 1960s, a decade and a half after WWII ended and the world (including Albania itself) had already moved on to more modern firearms.

(Albanian-manufactured Mosin-Nagant 91/30 rifle, the final production run of this legendary WWII rifle.) (photo via Armslist website)

(Albanian-manufactured Mosin-Nagant 91/30 rifle, the final production run of this legendary WWII rifle.) (photo via Armslist website)

(Enver Hoxha, the WWII guerilla who would become Albania’s dictator from 1944 – 1985.)

(Enver Hoxha, the WWII guerilla who would become Albania’s dictator from 1944 – 1985.)

(Mosin-Nagant M44s being looted by an Albanian civilian during the 1997 chaos.) (Associated Press photo)

(Mosin-Nagant M44s being looted by an Albanian civilian during the 1997 chaos.) (Associated Press photo)

The Cold War-era Albanian military overall was a blend of different generations (including WWII) of weapons serving alongside one another.

Albania during WWII

In April 1939, five months before WWII in Europe began, Italy invaded Albania. The invasion lasted a week and resulted in an Italian victory and Albania being reduced to a protectorate in Mussolini’s empire. The ease of the Italian conquest was largely due to the ineffective Albanian army and masked some serious flaws within the Italian invasion force. Those would later come home to roost during the Greek and North African campaigns of WWII.

Italy switched sides in September 1943 and Albania was in turn occupied by German forces. The main unit was the Wehrmacht’s 297th Infantry Division, an understrength unit inheriting the colors of a division lost at Stalingrad. The Germans did attempt to raise an ethnic-Albanian unit, the Waffen-SS 21st Gebirgs-Division “Skanderbeg”. This was a failure and it never reached divisional strength. It was largely destroyed in combat with Tito’s partisans in Yugoslavia.

Albania had little value to the Reich. While there was crude oil present there was no efficient way to ship it, and the country had no heavy industries which could be commandeered.

By mid-1944, Tito’s partisans in neighboring Yugoslavia controlled a vast swath of territory opposite Albania’s north and northeast. Adolf Hitler therefore decided to just abandon Albania. By the autumn of 1944, the southern part of the country had been abandoned and the last German forces anywhere in Albania left in December.

(Guerillas entered the capital Tiranë, or Tirana, unopposed in 1944. The soldier to the left has a Mannlicher-Schönauer, a rifle used by the pre-1939 Albanian army and WWII Greece. It could have come from either source. The other two men have captured Italian Carcano Mod.91s. The latter was used for some years in post-WWII Albania.)

Albania was now a political vacuum which was filled by Enver Hoxha’s communists.

Albania’s early post-WWII years, ex-Axis guns, and appearance of the Mosin-Nagant

During WWII Hoxha’s guerillas used either captured Italian or German rifles, or civilian hunting guns. From 1944 onwards, cross-border contact was established with Tito’s 3rd Division; the Yugoslav partisans now being so numerous that they formed conventional-sized units, and could spare some small arms. Here the first Mosin-Nagants probably entered the country.

The Allies never reached Albania before WWII ended and the first visiting Soviet military delegation did not arrive until well after Germany’s surrender in May 1945.

While a trickle of Soviet weaponry began to arrive in the late 1940s, during that time the army’s gear was largely ex-Axis equipment.

(Breda Mod.37 in an Albanian museum.)

Breda’s Modello 37 was a WWII Italian machine gun firing 8x59mm(RB). It is best remembered for its odd feed system, a 20rds cassette from which the receiver fed the chamber, and also to which the extractor seated empty casings back into. Post-WWII Albania inherited a decent number. The uncommon rebated 8×59 round was actually the first cartridge produced in post-WWII Albania, as it was unlikely to be sourced anywhere else in the communist world. These unspectacular Italian machine guns served at least half a decade after WWII in Albania, maybe longer.

(Albanian reissued 98k.)

Germany’s bolt-action 98k was the most common German weapon of any type in WWII. It fired the 7.92x57mm Mauser round. Hoxha’s guerillas already had captured some during WWII and more came quickly afterwards, donated by Yugoslavia.

The image above is from the 1959 film Kufitari, the significance of which is described later below. In this scene a border patrolman greets a rural village militiaman armed with a 98k, showing ex-German rifles still in some Albanian use at that late of a date.

(Albanian soldiers in ex-Italian helmets during 1950.)

So many surrendered WWII Italian Elmetto Mod.33 helmets were inherited by Albania that it was the lone type for the first six years. In the early 1950s the USSR began delivering WWII surplus SSh-40s to complement and eventually replace them. Albania’s helmets during the Cold War were a mish-mash: first the ex-Italian WWII Mod.33s, then the WWII Soviet SSh-40s, then a “side buy” of wz.50s from Poland, then a small batch of Czechoslovakian M-53s, then in 1969-1970 the Chinese GK80A. At any given time two or even three types were simultaneously in use.

(Albanian FlaK 37 in 1949.)

Germany’s FlaK 37 88mm combined AA / anti-tank gun, the “88”, is perhaps the most famous artillery piece of WWII. Postwar Albania operated at least four of these guns for certain, and maybe more. It is unlikely that they were left-behinds on Albanian soil, but rather donated by either Yugoslavia or the Soviet Union after WWII ended. The “88” above was at a 1949 welcoming ceremony for a visiting Soviet general delivering military aid.

other WWII kit in the Cold War-era Albanian army

The Cold War-era Albanian military was the large regular People’s Army (UPSh in Albanian) plus a 7,500-strong uniformed combat detachment of the Sigurimi secret police. At its start the UPSh was almost entirely foot infantry, and even in the 1980s it was 70% either still foot infantry or partially-mechanized motor rifle units.

There was a huge (over a quarter-million at its peak around 1985) second-rate militia called the FVVP, or Voluntary Self-Defense Forces in Albanian. It was equipped with older, often WWII, firearms. Membership was open to any adult Albanian. In the regular military it was derisively called “ushtria e vajzës” (the girl army) as roughly 65% – 70% of FVVP volunteers were women.

Finally there was a third tier. These were very small ad hoc militias in rural villages. Often this was just a gun locker with the armorer being a trusted communist, who would distribute rifles to the village’s adults in an emergency.

Albania started with no anti-tank assets (and no tanks either, for that matter). One of the first weapons the Soviets provided after WWII was 53-K towed 45mm anti-tank guns. This gun’s design had been quickly finished by Mikhail Loginov in 1937 after the original engineer, Vladimir Bering, was arrested in one of Stalin’s purges.

(WWII Soviet 53-K anti-tank guns in the late 1940s / early 1950s Albanian army.)

The 53-K fired a 45x310mm(R) AP round at 2,493fps muzzle velocity and was not a great design. During WWII it was sufficient against the Panzer III, but against the Panzer IV it was ineffective at anything but close range. It was useless against the Panther and Tiger. Production was halted in 1943 but of the 37,354 made, thousands survived WWII. Now in the postwar world it was considered even more useless and was ripe to dole off on satellites like Albania.

The ZiS-12 was a 3-ton chassis carrying a Z-15-4A anti-aircraft searchlight. Based on an early-1930s Soviet truck, about 4,800 of these were made in the USSR during WWII of which many survived.

During WWII radar eclipsed searchlights as the best method to target AA guns. By 1954, when the Albanian ZiS-12s above were photographed, not only had the USA centered its air defense on radar but was also beginning to field MIM-3 Nike-Ajax surface-to-air missiles.

Albania’s Cold War-era AA defenses included a WWII Soviet AA gun type, the 52-K. Designed in the 1930s, this hand-loaded 85mm weapon had a 7-man crew and fired 10rpm. The vertical slant ceiling was 34,448′.

(Albanian 52-K emplacement during the 1960s after the SKS had replaced WWII firearms for the gun crew. The battery was cued by the flagmen following directions from an off-mount fire control station.)

A big-bore WWII AA gun like the 52-K was designed to combat propeller-driven bombers like the Do-17 and He-111. By the 1960s it had zero chance against a B-58 Hustler or B-52 Stratofortress, and was way too slow-laying and slow-firing to take on tactical types like the F-105 Thunderchief. Starting in 1961, the USSR began to provide Albania with SA-2 “Guideline” surface-to-air missiles. Albania was, surprisingly, one of the first “Guideline” recipients on the basis of the Vlorë naval base being so close to Italy. The big WWII AA guns served alongside them in declining numbers into the 1970s.

(Strange streets for a Studebaker: unreturned WWII Soviet Lend-Lease G630s in the capital Tirana after being passed to Albania.)

The Studebaker G630 military truck was massively produced in the USA during WWII, often for Lend-Lease to the Soviet Union. After WWII ended Josef Stalin saw little need to either return them to the USA or pay for them, and one way to usefully “make them go away” was donation to obscure and insular allies, of which Albania fit the bill.

The lifespan of a WWII truck was usually not long as they were built to fill a need and ran hard during the war. By 1950, the Studebakers in the above photo were already half a decade old, maybe more, and had unknown mileage. None the less these were urgently needed in Albania as the army was desperately short of motorization.

(This 1949 photo shows an Albanian horse-drawn artillery unit. The pieces are 120-PM-38 heavy mortars. This 4.73″ mortar was successful in Soviet service during WWII and had a 3½ mile range. The 120-PM-38 folded flat for transport with the sights and other gear boxed on a limber ahead of the towed mortar. The riders are armed with the M44 carbine version of the Mosin-Nagant.)

(This 1954 photo shows an equine logistics unit still in service.)

The first Albanian armored combat vehicles were BA-64 armored cars. The Soviets built 9,110 of these lightly-armored vehicles during WWII. The BA-64 weighed 2½ tons and was armed with a machine gun.

(Albanian BA-64 on parade in 1949. This particular example was of the USSR’s “expedient production series” during WWII, with just one headlight and other shortcuts.)

Obsolete in a post-WWII context, the USSR began delivering these in the late 1940s. Surprisingly Albania still had some in use in the 1970s.

The BA-64s were joined by SU-76 assault guns. Despite their appearance, these vehicles (which were the second-most produced Soviet tracked type of WWII, after the T-34) were not tanks but rather self-propelled anti-tank guns. They were lightly armored and open-topped.

(Albanian SU-76 in the early 1950s. This turretless WWII vehicle’s ZiS-3 76mm gun had limited traverse, beyond that the whole vehicle needed to move to aim.)

The Soviets ended SU-76 production when WWII ended and almost immediately began doling them out to communist allies. Albania received a small number. Due to Albania’s small number of armored fighting vehicles, they were used as substitute tanks until sufficient T-34s were available, and then in their intended role by which time they were already obsolete.

(Communist Albania’s crest was, as seen on this SU-76, a black double-headed eagle with red star inside a wheat wreath.)

Shortly after the SU-76s were delivered, the USSR agreed to supply T-34 tanks, which were in Albanian service by 1949.

(Albanian T-34-85 in 1949, shortly after this legendary WWII type entered service in the country.)

The T-34-85 was arguably the best tank of WWII and set the template for the MBT (main battle tank) concept of the Cold War. Well-armored, durable, and armed with a 85mm main gun, the T-34-85 was still a competitive tank in the Cold War era. Albania continued to use these tanks into the 1970s and some were in reserve when communism ended in the 1990s.

(Albanian T-34-85 tanks during the Cold War.)

The PPSh-41 was a mass-produced (over 6,000,000 made) WWII Soviet submachine gun firing the 7.62x25mm Tokarev cartridge (1,540fps muzzle velocity) from either a 35rds box magazine or 71rds drum.

(Albanian army soldiers with PPSh-41 submachine guns in 1949. Surrendered WWII Italian Elmetto Mod.33 helmets were still the standard-issue headwear.)

(Border Patrolman with a WWII PPSh-41 submachine gun in the early 1960s uniform style. “RPSH” on the boundary pylon is “People’s Republic of Albania” in Albanian.)

Weighing only 8 lbs, the PPSh-41 was perfect for Soviet close-quarters battle during WWII and after the war, the Albanians found it ideal, being more compact and lighter than a full-length bolt-action rifle but with full-auto capability; albeit using a pistol cartridge. The PPSh-41 was especially popular in Albania’s national border patrol which had to cross long distances of difficult terrain on foot. The PPSh-41 was one of the first firearms received as Soviet aid in the 1940s and remained in daily use to the fall of communism. Limited use was made thereafter and some were still in use during the early 2000s.

(Albanian soldiers march with WWII PPSh-41s in 1977. The Albanian military showcased female units often, illustrating gender equality they felt superior to that of NATO or the Warsaw Pact during that era. Here the 35rds banana magazine is used.)

Kufitari (Border) was an Albanian government-funded movie filmed in 1959. Sort of a docu-drama glamorizing national border defense, it did offer an interesting and rare public glimpse into the firearms and uniforms which Albania used in that time frame. Most of the guns were WWII vintage. The title scene above shows a PPSh-41.

(In another scene of Kufitari, a border patrolman with PPSh-41 greets an official. Here the characteristic 71rds drum mag is in use.)

Even more common in Cold War-era Albania was the PPSh-41’s WWII Soviet “brother”, the PPS-43. This submachine gun was intended as a cheaper, quicker complement to the PPSh-41 and was made largely of stamped sheet metal. The PPS-43 fired the same Tokarev cartridge from a 35rds box magazine. About 2,000,000 were made by the USSR during WWII.

(Albanian soldier with PPS-43 submachine gun. The helmet is the WWII Soviet SSh-40. The photo likely dates to the 1960s.)

To say the PPS-43 was common in Albania would be an understatement; along with the SKS it is quite possibly the most ubiquitous firearm in the country’s history. Albania began receiving these, from Yugoslavia and then directly from the USSR, soon after WWII ended and imported many thousands. Additional examples came after the Albanian-Soviet Split in the form of Chinese-made guns.

(Female soldiers with PPS-43s. The hairstyles and uniform type would seem to fit the 1970s.)

The PPS-43 was still in Albanian service in the 2010s.

To replace ex-Axis machine guns in the late 1940s, the Soviets provided Albania with DP-27 machine guns. This WWII weapon fired the 7.62x54mm(R) cartridge (the same as the Mosin-Nagant) from an overhead 47rds pan magazine.

(Albanian troops with DPs in 1949, shortly after this WWII type was introduced. Here the pan magazines are not mounted. These soldiers are still wearing surrendered Italian Elmetto Mod.33s.)

(A DP mounted on the sidecar of an Albanian army motorcycle during the 1950s, with the pan magazine.)

The pan magazine allowed for a larger capacity while using a rimmed cartridge. It also took a long time to refill, as each round had to be inserted one-by-one.

The DP had a very long service in Albania, even as the RPK entered service in the 1960s. China had cloned the design after WWII and provided spare parts and maybe even replacement guns after Albania left the Soviet sphere. The DP was still a frontline machine gun in the late 1970s and was a reserve and second-line weapon after that.

(Albanian DP gunner during a drill. The GK80A helmet did not begin to enter service until 1969 so this photo dates from the 1970s or later.)

In 2005, during Albania’s NATO accession progress, the DP was still listed as “in service, being withdrawn”.

Albania: in & out of the Warsaw Pact

A lesson in Albanian history is beyond the scope of this writing. However the nation’s strange, winding journey in the communist world between WWII and 1990 directly intertwines with the Mosin-Nagant, and especially why Albania became the last country to produce that rifle.

During and immediately after WWII, neighboring Yugoslavia was Hoxha’s main benefactor, followed by the Soviet Union. By 1949, there was already a clear split with Yugoslavia and by the 1950s the two countries were essentially enemies.

(An Albanian MP in 1949. His firearm is a Sten Mk.II, this WWII British submachine gun undoubtedly having been provided by Yugoslavia where, during WWII, it was a guerilla weapon supplied by the Allies. Guns from the western WWII Allies left Albanian service even faster than ex-Axis arms.)

Albania was a founding member of the Warsaw Pact in 1955. A “marooned stepchild”, it was the only member to lack a common border with any other member. It never really fit into the alliance’s grand strategy and as far as Soviet military aid, was usually last in line.

(Albanian troops clashing with the Greeks on their common border in 1949. The light machine gun is the water-cooled PM M1910 of WWII Soviet use. It fired the 7.62x54mm(R) cartridge – the same as the Mosin-Nagant – from a 250rds belt. Small numbers were provided as Soviet aid to Albania. The soldiers are still wearing surrendered WWII Italian helmets.)

The only appreciable benefit to the USSR was the new Pasha Liman naval base near Vlorë. The Soviets planned to forward-base twelve submarines here. The base (which still exists) is actually in three parts, the Pasha Liman facility near Oricum, a smaller base near Vlorë itself, and Sazan Island in the Gulf Of Vlorë.

Sazan is its own strange story. It is a 2¼ miles² rock in the Adriatic’s Strait Of Otranto. Visible on a clear day from Italy, it was from the 1910s to the end of WWII legally part of Italy, known as Saseno. As part of the 1947 final settlement for Italy, Sazan was returned to Albania. During the first two decades after WWII this was particularly bitter within the postwar Italian navy; the general consensus being that the island was wrongfully taken despite being closer to Albania, and would be “recovered” when the time was opportune. In the 1950s Albania fortified Sazan to an almost comical degree, with obsolete concrete bunkers and gunhouses more apt to 1920s combat than the Cold War. A grim CIA report of the 1950s claimed it was built by WWII German POWs still in Soviet captivity, who were presented as a human gift from Stalin to Hoxha. If true, the fate of the Germans is unknown. Sazan was also a repository for Albania’s small chemical weapons stockpile.

(An artillery ammunition bunker on Sazan.) (photo via Albanian Ministry Of Defense)

Pasha Liman, built from scratch, was costly for the Soviets to build and was leased at an inflated price.

Albania’s exit from the Warsaw Pact was protracted and began even before it joined. When Josef Stalin died in 1953, the first cracks appeared as Nikita Krushchev tried to prod the communist world away from the “personality cult” style of governance which Hoxha favored. In June 1954 Krushchev circulated a letter bemoaning how hardline rhetoric had basically guided Yugoslavia into the embrace of the west. To Hoxha, this was outrageous as he was hoping for even more pressure to be put upon the “deviants” in Yugoslavia. None the less Albania joined the Warsaw Pact the following year. In 1956, Krushchev gave his famous speech denouncing the stalinist style of communism, which infuriated Hoxha.

Relations briefly improved after the Soviets crushed the Hungarian Uprising, which Hoxha viewed as the proper way to handle discontent. In 1957, the USSR gave Albania a huge cash loan and simultaneously forgave the previous ten years worth of overdue accounts.

A 1958 economic planning conference laid out the Soviet view that Albania’s economy should remain small and agricultural, which naturally clashed with Hoxha’s dream of Albania being an industrial power. Specifically to the Mosin-Nagant run later, the Soviets did not envision any arms industry at all in Albania, contrasting to fellow allies Poland and Czechoslovakia which had some self-sufficiency in weaponry.

(Because of the dependence on foreign aid from different sources, Albania’s army had weapons from several generations concurrently in service at any time. Here in the late 1960s or early 1970s, an early Cold War-era SKS is to the rear while a later Cold War-era AK-47 is to the front. The middle gun is a WWII weapon, the Goryunov SG-43. This WWII Soviet LMG fired the 7.62x54mm(R) cartridge – the same as the Mosin-Nagant – from a 250rds belt. The clever wheeled mount could be upset with the trails becoming a pintle, so the weapon could elevate against low-altitude aircraft. Albania really liked the SG-43 and they remained in service past the end of communism.)

(Because of the dependence on foreign aid from different sources, Albania’s army had weapons from several generations concurrently in service at any time. Here in the late 1960s or early 1970s, an early Cold War-era SKS is to the rear while a later Cold War-era AK-47 is to the front. The middle gun is a WWII weapon, the Goryunov SG-43. This WWII Soviet LMG fired the 7.62x54mm(R) cartridge – the same as the Mosin-Nagant – from a 250rds belt. The clever wheeled mount could be upset with the trails becoming a pintle, so the weapon could elevate against low-altitude aircraft. Albania really liked the SG-43 and they remained in service past the end of communism.)

During this time frame Hoxha began to look to Mao’s China as an alternative to the USSR. He felt the maoist strain of marxism more closely aligned to his own than anything now coming from Moscow, and the Chinese were eager to invest in development of Albania to gain a diplomatic beachhead on the European continent.

In April 1961 Albania signed an omnibus trade and assistance treaty with China and voided the same with the Soviet Union. In May 1961 the lease for the Pasha Liman base was cancelled, and Albanian troops training in the USSR were ejected in response.

In 1962 Albania ceased participation in the Warsaw Pact. Hoxha kept Albania legally a member in hopes that the next Soviet leader might return to stalinism. For its part, the Warsaw Pact did not want a precedent of expelling a member. After the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, Albania did formally withdraw, by then an afterthought.

Albania’s production of the Mosin-Nagant

Quite surprisingly, in 1960 – a full decade and a half after WWII’s end – the communist government made the decision to manufacture the Mosin-Nagant in Albania. With the Albanian-Soviet Split about to culminate, the need for domestic arms production, even something as basic as a WWII bolt-action rifle, was perhaps apparent.

The Mosin-Nagant family left Soviet production in 1948, Hungarian in 1954, Polish and Romanian in 1955, and Chinese in 1956. So the decision to start Albanian production from scratch in the 1960s is unusual.

After a planning and tooling-up period in 1960, the whole small Albanian production run was made in 1961.

The Albanian-made Mosin-Nagant is the 91/30 long rifle version. The overall length is 48½” and the weight is 8¾ lbs. Like any other 91/30 it fires the 7.62x54mm(R) cartridge at 2,838fps muzzle velocity from a 5-round stripper-loaded internal magazine. In all respects it is a true 91/30; but with some interesting caveats.

(Albanian-made Mosin-Nagant 91/30.) (photo via 7.62x54r.net website)

The Albanian 91/30 buttstock has a “high comb” shape, similar to the Chinese Type 53 clone of the Mosin-Nagant M44 carbine. The specific receiver style (round low wall) is that of final 1940s Soviet Mosin-Nagant production at Izhevsk; this coincidentally being the specific copying template the Chinese used for the Type 53. The riser which the stripper slides into is more rounded than Soviet-made Mosin-Nagants. The sling hole is slightly more to the rear than either Soviet or Chinese rifles.

(Buttstock of an Albanian-made Mosin-Nagant.)

The Albanian-made 91/30 has unique rear sights, not common to either Soviet or Chinese variants. It is a pinned sleeve-base type, like the Chinese carbine, but longer and graduated 1 to 20 (100 – 2,000 meters, or 109 – 2,187 yards).

(Top view of the Albanian sight.) (photo via 7.62x54r.net website)

(Side view of the Albanian sight.)

There are several other minor differences. The knob of the cocking safety is a different diameter, and the front of the magazine floor “rides up” into the rifle in a somewhat more elongated way.

The official Albanian designation was “Pushka 7,62 Mod 61” (“7.62mm Rifle, Model of 1961”).

production run size

Now in the 2020s, amongst Mosin-Nagant historians and enthusiasts, the biggest point of debate is exactly how many Mosin-Nagants Albania manufactured in 1961.

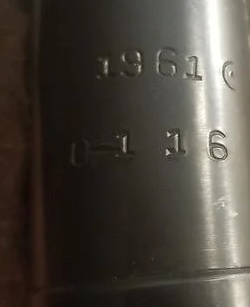

The markings on the receiver are very basic, just “1961” with the Albanian proofmark, and then a four-digit serial number.

(photo via 7.62x54r.net website)

Each serial number begins with the requisite one, two, or three zeroes so it may possibly be deduced that from the very start, the run was never intended to be any higher than four digits at the most.

Fewer than two dozen Albanian-made 91/30s are known to exist in private collections. Of these, serial numbers vary from teens to the 140s.

Thus a commonly quoted estimate for the total made is only 150 rifles. While certainly possible, this would be an extremely small run and perhaps contrary to the likely reason for the production run to even happen, as discussed below. It is also maybe an instance of what mathematicians call “availability bias”, which is to say for example, if ten people have pennies and dimes in their pocket; it positively proves that coins up to 10¢ are made but fails to definitively disprove the existence of higher denomination coinage.

Even by ex-Iron Curtain standards, Albania’s Cold War-era arms production documentation is practically nil today. Part of this was the paranoid over-classification of military data during the Hoxha era, and another part is the ransacking and loss of archives in 1990 and again in 1997.

reasoning

It is likely that the whole 1961 Mosin-Nagant project in Albania was simply intended as a dry run for the firearm Albania truly intended as its first domestic mass production, the early Cold War-era SKS. That gun (called “July 10 Rifle” locally) was already in widespread service from import orders and was put into Albanian mass production in 1967, six years after the Mosin-Nagant project ended.

The goal may have been to simply walk through the process of acquiring the tooling, allocating skilled and unskilled labor in adequate numbers, writing up the correct sequence of work orders, scheduling transportation, and so on. Any manufactured rifles which came out the other end would be a secondary consideration.

A counter-argument is that if this was indeed the objective, the Albanians could have just went straight to the SKS with little added complexity. A possibility here is that some Mosin-Nagant manufacturing jigs had already been provided by the USSR and, with Chinese assistance, Hoxha just wanted to get some type of rifle (however obsolete) into domestic production ASAP as a political act during the break with the Warsaw Pact. The SKS would then come later.

Almost certainly Chinese technical assistance was provided for the project. Military advisors from the PRC reorganized and streamlined Albania’s entire defense structure top-to-bottom in 1960 – 1961, the same time frame as the Mosin-Nagant project. Numerous similarities between the Albanian-made 91/30 long rifle and the Chinese Type 53 (the clone of the M44 carbine) would further indicate this.

Why the Albanians decided on the 91/30 long rifle in 1960 is inexplicable and will probably forever be a mystery. WWII already illustrated the advantages of a more compact and lighter standard service rifle, and Albania was already using Soviet-supplied Mosin-Nagant M44 carbines and Chinese Type 53s (their M44 clone) anyways. Production-wise, there is no manufacturing disadvantage or advantage of making a long rifle vs a carbine Mosin-Nagant.

Based on the few private owners who have shared their thoughts, Albanian-made 91/30s shoot no better or worse than any other. Of the known examples in private hands, all are in good condition (…and compared to the horrible shape of other ex-Albanian Mosin-Nagants; pristine) and may have never been issued. On the other hand, at least one known example has replacement parts taken off a Soviet-made 91/30, indicating that perhaps some were issued after all.

Serials are present on the receiver, the bolt, and the fixed magazine. Curiously, some are “off” by a few digits, like 0095 on the receiver and bolt but 0097 on the magazine, or 0111 on the receiver but 0112 on the other locations. However the “offset” does not travel upwards through the known run, as would happen if one mismatched gun threw the rest out of synch. The explanation is unknown and in any case most are fully-matching.

Amongst Mosin-Nagant collectors, an Albanian-made 91/30 is a “unicorn variant”; a rarity which most collectors hope to someday add to their rack. In the United States, they have sold in excess of $2,100 with a “common” Mosin-Nagant going anywhere from $375 – $700 in the 2020s.

ammunition

In 1960, Chinese advisors overhauled Albania’s domestic ammunition production scheme. Previously since WWII, it had been a haphazard affair scattered around the country. Ammunition would now be made at three factories: Gramsh, Poliçan, and Plasëse. The scheme was running by early 1962. Naturally one caliber produced was 7.62x54mm(R), for the Mosin-Nagants and other WWII-era guns employing this cartridge.

Albanian headstamps are simple, just the numeral 3 and then a two-digit year code. The 3 maybe references the three plants, in any case all three of them used a 3.

(Albanian-made 7.62x54mm(R) round produced in 1987.)

The most common type is steelcore ball but tracer and blanks were also made. Albanian 7.62x54mm(R) is considered of poor quality, especially if made after 1977. Another tidbit is that as it entered the surplus market, packaging was often found short. For example a standard combloc 7.62x54mm(R) 440rds spam can made in Albania is labelled & sealed as such, but can actually contain as few as 395rds.

(Albanian spam can slip from 3 December 1985.)

Even after the widespread use of the SKS and AK-platform guns which required 7.62x39mm Soviet, 7.62x54mm(R) remained in production. Headstamps from 1988 are known to exist and it may have been produced all the way up to the very end of communism in the 1990s.

the Mosin-Nagant’s service history in Albania

While the Albanian-made Mosin-Nagants did not appear to have widespread issue, the overall design itself certainly did.

Albania’s history with the Mosin-Nagant started even before WWII. During the late 1910s or 1920s, a quantity of Mosin-Nagant M1891 version long rifles were acquired. In 1928 the Benny Spiro company of Hamburg, Germany acted as a go-between for Albania and Finland, the former swapping Mosin-Nagant M1891s from World War One for Arisakas from the latter (touched on later below).

Late during WWII 91/30s and M44s began to filter across the border from Tito’s partisans. After WWII ended, more were obtained as military aid from both Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union.

(Albanian soldiers with the M44 carbine version during a 1949 parade in Tirana.)

(Albanian navy sailors with Soviet-supplied M44 carbines in the late 1940s / early 1950s.)

(Soviet-supplied Mosin-Nagants in an Albanian army parade during 1952. The headgear is the SSh-40, a Soviet WWII helmet, which began to replace surrendered Italian WWII helmets in this time frame.)

How many Mosin-Nagants the Soviets supplied Albania before the Albanian-Soviet Split will probably never be known. In the 9½ year interim between WWII ending and the Warsaw Pact’s signing, there were several avenues for eastern European satellites to be armed including secret state-to-state gifts, formal state-to-state sales in Moscow, on-site transfers by Soviet commanders at the conclusion of a joint exercise, three-way deals between communist armies, and so on.

(A Soviet WWII-production 91/30 long rifle which was later transferred to Albania. This particular 91/30 was later imported into the USA by Century. It is not uncommon for Albanian Mosin-Nagants with Izhevsk or Tula marks to have them buffed out; this being done after the Albanian-Soviet Split.) (photo via Liberty Tree Collectors)

Even as deliveries of the WWII Mosin-Nagant continued, the postwar SKS began to enter Albanian army service. The SKS might be considered *the* classical Cold War gun of Albania. From the mid-1950s to 1961 they were supplied in large numbers by the USSR to replace WWII guns, then in 1960 China began providing its SKS clone (the Type 56), and finally in 1967 Albania itself began SKS production. Later, even as Chinese-supplied AK-platform guns were being provided, Albania made the SKS from 1967 – 1972, and again from 1975 – 1978 when the ASh-78 Tip 1 (Albania’s AKM clone) entered production.

(Albanian heavy artillery unit still with the ML-20 of WWII but having upgraded from WWII guns to the SKS as the crew’s small arms. The ML-20 was a 152mm piece produced throughout WWII, then being supplied to Soviet allies. Its range was 10½ miles. Along with the smaller 122mm M-30 also of WWII, the big ML-20 was first-tier Albanian artillery until 1974.)

Albania’s firearm progression was thus not at all linear, hopscotching around generations. Beginning in 1960 Chinese Type 53s (the post-WWII clone of the Mosin-Nagant) were provided as military aid, first before Type 56 SKS clones and then for a while, alongside them.

(A Chinese-made Type 53 (Mosin-Nagant M44 carbine clone) manufactured in Chongqing during 1955 and transferred to Albania in the mid-1960s. The Albanian nomenclature for Type 53s was “Karabina Mod 53 Kalibër 7,62”, the slang was “Karabina Kinez” or Chinese Carbine.)

A total of 39,860 Type 53s were delivered by China to Albania before aid switched fully to the SKS and AK-47 clones.

(Mosin-Nagant 91/30 in a 1967 training film, as described below.)

The image above is a still from a 1967 training film which highlighted Hoxha’s “People’s War Concept” stressing the combined efforts of the regular Albanian army and reserves, then the FVVP, then rural militias, and finally plain civilians, against the supposed three-headed threat of Yugoslavia, NATO, and the Soviet Union. This training film, almost tragicomic in hindsight, showed how infantry would support villagers making hollow plaster “pumpkins” filled with gunpowder and lit with a string wick. Once lit, the “pumpkins” would be gently rolled down a hillside to somehow repel a modern army. Had there been a real war, and this actually tried, the outcome would have likely been worse for the villagers than the invaders.

(Albanian soldier with a Type 53 in the late 1970s.)

By 1980 the Mosin-Nagant in all its guises had been replaced in top-tier Albanian service, yet many thousands remained in reserve, second-line militia, or storage units.

(Albanian reservists drilling with Mosin-Nagants in 1972.)

(The 50 Lek banknote of 1976 featured a Mosin-Nagant 91/30. The Lek was not a worldwide forex currency between WWII – 1991, and was worthless outside Albania.)

in use & combat

Albania never fought an international war between the end of WWII and the end of communism. None the less, Albania’s Mosin-Nagants did see internal conflict in that time.

Along with Tito in neighboring Yugoslavia, Albania’s Enver Hoxha acted as Stalin’s frontman for helping the communists during the 1940s Greek civil war. As the Greek communist’s fortunes waned, fighting moved closer to the Greek-Albanian border and the de jure armies of both countries sometimes engaged each other on the border in 1949.

(Albanian troops with Mosin-Nagant M44 carbines in 1949.)

An obscure episode of the Cold War was a joint British-American effort known as operation “Valuable” in the UK and “BGFIEND” in the CIA. Hatched in 1949, this was a scheme to insert anti-Communist Albanians into Albania (“LCBATLAND” in CIA code) to begin a nationwide insurrection or military mutiny. The plan was to sneak small teams trained in Malta (still then a British Crown Colony) ashore in Albania via traditional Adriatic fishing boats where they would rile up the population, gather intelligence, and then egress out over the Greek border.

The first missions were in late 1949 and at least some of the men made it out to Greece. They failed to agitate a rebellion but did gather intelligence. Unknown to all, the project’s British UK-USA liaison, Harold A.R. “Kim” Philby, was a Soviet spy. Successive missions failed dramatically and during the last, in April 1952, Albanian infantry was awaiting, rifles ready, at the insertion point.”BGFIEND” was a flop. Philby was unveiled in January 1963 and fled to the USSR where he lived the rest of his life.

Early in the Cold War Hoxha had other internal challenges barely known in the west.

During the late 1940s at least, there were amazingly still bands of “Legalititi” or “Zogists” loyal to the pre-1939 King Zog, whom they wished to see restored to the throne. An assessment by the CIA in October 1951 (declassified in 2000) stated that even then, monarchist guerillas were still active against the communist army which may or may not have been true. In February 1951 there was some sort of explosives attack against the Soviet embassy in Tirana, and some post-WWII shootouts with rebels were too big for the government to hide from the public and explained away as “foreign aggression”.

(An Albanian alpine unit with Mosin-Nagant M44s in 1959. Albania’s internal troubles were usually in rural areas, often in the mountains, especially mountains near the Yugoslav and Greek borders.)

Another group was across the Adriatic in Italy. Bloku Kombetar Independent was created in early 1946. It sought to overthrow Hoxha but was anti-monarchist. A 1951 CIA assessment described it as “fascist” which is dubious, and the organization itself stressed a desire to “resume a close Italian-Albaninan partnership” which may have been simply a guest telling his host what he wanted to hear. Regardless, BKI was partially funded by the Italian navy, and the Italian air force dropped BKI spies and saboteurs into Albania along with periodic drops of anti-communist leaflets during the early 1950s. The sabotage accomplished little, and the propaganda failed to incite a general uprising, but was apparently widely enough read that the communists could not hide it and had to make public complaints. These missions petered out as radar, SAMs, and jet fighters entered Albanian service.

By 1960 this was all over, and there was no realistic chance of Hoxha being overthrown. Albania’s Mosin-Nagants would not see combat again during the Cold War. Oddly enough, they would afterwards.

the 1997 anarchy

Enver Hoxha died in 1985. Albanian communism limped along another half-decade. In December 1990, protests began and the country became a democracy in 1991.

In 1992 – 1993, many Albanians began investing their life savings in get-rich-quick “pyramid” scams. It’s easy to poke fun today but it should be remembered that almost nobody in the country had experienced capitalism for many decades. These scams crashed in January 1997 costing many Albanians everything and collapsing the national banking system.

People took to the streets demanding the government reimburse them which, obviously, it had no way of doing. Police and the army temporarily restored order in northern and central Albania, but failed in southern Albania. This was the first of two key events.

Albania’s south tended to oppose the party in power, and citizens armed themselves with stolen guns, which they then use to overrun police stations and army bases, getting more guns, starting a snowball effect.

(Mosin-Nagants being looted in southern Albania in 1997.)

At the same time, organized crime gangs in southern Albania saw the chaos as an opportunity to access military levels of firepower to use against each other or police. In particular, the Çole gang in Vlorë – the city housing the former Soviet naval base – had previously concentrated on petty shootings with the rival Muko gang. By the fourth week of February 1997, the Çole gang had amassed such a war stockpile (including tanks, AA guns, and even a small warship) that it had destroyed all law enforcement in Vlorë and was ruling the city like a criminal duchy.

The second fateful event happened in March 1997. Known as “hapje e depove” (“opening of the depots”), the government put into action a Hoxha-era contingency plan to arm adults with second-tier firearms (SKSs and even WWII weapons) in the event of a national emergency. The goal was that Albanians might protect themselves against both the southern rebels and the criminal gangs. As it happened, the floodgates opened and people just turned the rifles on the armorer and took whatever else they wanted. Combined with the previous lootings in the south, Albania was now flooded with military firearms.

(Mosin-Nagants being looted in 1997. The one slung on the man in blue is in rough shape; the rear sight is dangling and the fixed magazine is missing.)

(Mosin-Nagants being looted in 1997. The one slung on the man in blue is in rough shape; the rear sight is dangling and the fixed magazine is missing.)

The result was predictable. Although there was some residual effect towards the original goal (a rebel assault on the capital Tirana in repelled in March) any benefit was overshadowed by the problems this decision caused.

For starters, not everybody grabbing free guns was on the same side. Small pockets of anti-government rebellion began to pop up in the rural north. A bigger problem was that while the act was intended for civilians to protect themselves against crime, some civilians just instead became criminals themselves. For example in the northern city of Shkodër, looted military arms were used to blast open a bank vault and thieves made off with the American equivalent of $6 million of Lek banknotes. (As of mid-2021, the robbers have yet to be apprehended.)

Mosin-Nagants were not the most-looted item, at least from armories near urban areas. Naturally AK-platform weapons were most desirable, while SKSs most common as there were just so many of them. Other weapons (machine guns, hand grenades, pistols, RPG-7s) were looted. Bolt action rifles from WWII were generally the least desirable, but as depots were cleaned out, they were looted all the same.

(A looted Tokarev TT-33 handgun. This was either an ex-Soviet WWII weapon or the Type 54, the postwar Chinese-made copy.) (Associated Press photo)

(A looted Tokarev TT-33 handgun. This was either an ex-Soviet WWII weapon or the Type 54, the postwar Chinese-made copy.) (Associated Press photo)

(As the chaos continued, what remained of the police and army established amnesty turn-in centers. This one in March 1997 doesn’t look to have many customers. In the foreground is a WWII-era SG-43, and behind it a Cold War-era DShK heavy machine gun.)

(As the chaos continued, what remained of the police and army established amnesty turn-in centers. This one in March 1997 doesn’t look to have many customers. In the foreground is a WWII-era SG-43, and behind it a Cold War-era DShK heavy machine gun.)

Unimaginable quantities of small arms ammunition was stolen, in any and all available calibers.

(The army base at Fier in southern Albania was picked clean of both guns & ammunition. Here endless empty combloc ammo shipping crates lie in front of a warehouse. By late March 1997 the only things remaining at this base were unwanted army sundries including Chinese-made tin mess kits.)

(The army base at Fier in southern Albania was picked clean of both guns & ammunition. Here endless empty combloc ammo shipping crates lie in front of a warehouse. By late March 1997 the only things remaining at this base were unwanted army sundries including Chinese-made tin mess kits.)

As 1997 went on, the looting seemed to acquire a psychological frenzy, with nonsensical things like air-to-ground rockets or naval ammunition also being taken.

(In March 1997, looters in a stolen army truck hooked it up to a MiG-17 “Fresco” and drove away. The theives had no way of flying the jet and nobody to sell it to. This was one of three warplanes looted this way in 1997.)

(In March 1997, looters in a stolen army truck hooked it up to a MiG-17 “Fresco” and drove away. The theives had no way of flying the jet and nobody to sell it to. This was one of three warplanes looted this way in 1997.)

In mid-April 1997 the Italian militay deployed across the Adriatic, restoring a semblance of order in Tirana and key port cities and helping Albanian authorities to regain civil control.

(Italian troops patrolling Vlorë for the first time since WWII.) (Associated Press photo)

In June 1997, by some small miracle an election was managed to be held, and by July the chaos subsided.

end of the road

An audit of what was looted in 1997 included 549,775 rifles; 106,225 other weapons; 1.5 billion rounds of ammunition; 3,500,000 grenades or similar items; and approximately 1,000,000 other miscellanoeus lethal items; many of these being anti-tank mines of which Hoxha had hoarded in absurd quantities.

When the 1997 chaos started, the Mosin-Nagant had already been largely relegated to rural militia or storage for about 15 years. In that interim, the government (first the tail end of the communist regime, then the early democratic government) may have already started to scrap some.

As a very bizarre footnote to this tragedy, one Albanian report on the looted guns mentioned an unspecified number of “pushkë japonez të tipit arisaka” (Japanese Arisaka-type rifles). As mentioned earlier, before WWII Albania had swapped early-model Mosin-Nagants for Finnish old Type 30 Arisakas. If these still existed in Albania in 1997 they would have had to have made it through the Italian invasion, then all of WWII, then 52 years of storage which are pretty long odds. Another possibility is that China donated some North China Type 35s (a post-WWII 7.9x57mm Mauser version of the WWII Arisaka Type 99) during the 1960s, which Albania never then never issued to any unit. Nothing more was ever said of these guns, but in whatever form they must have existed for the Albanian auditor to make note.

Of all the guns looted in 1997, only 40% had been recovered by December 2019.

Around the turn of the millennium, the USA pressured Albania to begin reducing its war reserves, which were now grossly disproportionate to the post-communism army’s reduced size. Approximately 133,000 “firearms” (categorized as anything from pistols to light artillery) were destroyed. Of these 133,000, 11,000+ were SKSs with the balance being everything else including Mosin-Nagants. In 2019 the Albanian government set a goal of collecting all illegal military firearms no later than 2024, which considering its limited success in the previous 23 years seems a lofty goal. Any obsolete types (of which the Mosin-Nagant fits the bill) will be destroyed.

While the very few Albanian-made 91/30s are very valuable, there is limited collectibility of ex-Albanian Mosin-Nagants in general. Because of the ongoing destruction program, it is unlikely that many more will enter the private market.

(Albanian soldier with Mosin-Nagant in 1959.)

(Albanian soldier with Mosin-Nagant in 1959.)

a footnote: the “last” Mosin-Nagants

While Albania’s 1961 run was certainly the last serial production of the Mosin-Nagant from scratch to the original design, there was a related rifle manufactured in tiny quantities after that. Finland’s M39 has different furniture with a completely different buttstock, different sights, and other minor changes. During the early 1970s a very tiny number of M39s were assembled for niche roles; these being the last of the Finnish variants and reusing some Russian parts from older rifles. Thus it is subjective if Albania or Finland “made” the very “last” ones.

I want to give a hat tip to the website http://www.7.62x54r.net which originally inspired me to write this. It is a very high-quality website and one of the best firearms-related resources I have stumbled upon on the internet. -JWH (author)

LikeLike

From early 70’s the standart assault rifles of all regular units of albanian army have been SKS and AK-47(including indigenous copies), RPD machine guns as squad based weapon and RPG-7 as platoon based weapon. In same time artillery fire suport units were based at D-20 and D-30 howitzers (and chinese copies) and in some extent to M-46 130 mm gun and chinese 130 mm MLRs which have been modified dubbing the number of tubes per truck. So no tactical missiles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very Interesting article indeed but in need of some corrections. Since 1943 British SOE missions in Albania delivered by parachutes amounts of British and Axes captured weapons. Communist Yugoslavia did not provide sizable amounts of weapons to Communist Albania but until 1948 took whatever it could lay its hands on.

Soviet Axis captured weapons were shipped through Albania, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria to Communist guerrillas in Greece. Following their defeat in 1949 many of them entered Albania where they handed over all their weapons.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.

LikeLike

One of your best entries yet. Interesting insights into the amount of ex-Italian gear used by the Albanians immediately after the war.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks that was a really interesting article.

Albania has fascinated me since the early 80s when as a geeky teenager I used to monitor what I think was the only radio telex link out of Albania using a radio bought from Curry’s and a Commodore 64 computer. I don’t know how but I found that every weekday at 4pm the Albanian PTT transmitted all the telexes out of Albania to an unknown location. Often there were no telexes to be sent but sometimes there were 3 or 4. Weirdly all of the messages were in English and non were encrypted.

So I had to run home from school every day to catch these transmissions which were an amazing insight into Albania’s links with the rest of the world. There was a trade deal with China gone wrong where they had got some 2nd hand gun boats in exchange for some Albania copper. The Albanians started to complain about the quality of the gun boats and soon had to cope with the Chinese moaning about the quality of the copper , so there wasn’t a great deal of socialist unity. The oddest of the telegrams came from what seemed to be part of the Cambodian Royal Family who had somehow washed up in Albania and who sent birthday telegrams to European royalty.

Anyway keep up the good work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is amazing to have stumbled onto that!

LikeLike

only 150 made? long version. Sniper rifles?

LikeLike

I havent seen or heard of any with the PU scope mount so I doubt it.

LikeLike

The foreign military force that intervened in the 1997 pyramid crisis was not just Italian, it was multinational. There was a lot of grumbling in Greece that the Simitis government failed miserably to secure that the Greek detachment would protect the Greek minority in the south, but instead was deployed in the center of the country. I remember that at Argyrokastro (Girokaster per the Albanians) there was actually a march by the locals, we want a Greek force not a Romanian force which is what they got. A lot of the weapons looted from the Albanian stores ended up in the hands of the Kossovo Liberation Army, but also in the hands of criminals in Greece and beyond. I wouldn’t be surprised in they are right now in Syria, Libya, Yemen and the other active war conflicts. In the Greek media at the time the talk was that Albania had one Kalashnikov for every two inhabitants, likely an estimate coming from Greek intelligence.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Albania definitely did produce 7.62x54R ammunition into the 1990s. I have some 1990 dated surplus.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Albania making the last SKS’s was known to me, and those are commonly available in the US since many were imported. I never knew they even made MN’s! I enjoyed this post, as always. Thanks.

And to the guy above that was monitoring Albanian wireless radio telexes…wow. Damn. That is next level nerd stuff (with admiration).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Spent time in Albania in 2000’s. Didn’t see 91/30s but did see lots is WWII hardware; BREN guns, MG-34/42 among them. Soviet bolt-action AT rifles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

those old PTRDs (the A/T rifles) were common in Bosnia during the mid-1990s; they were used to snipe through the sides of civilian buildings

LikeLike

14.5 will do the job.

LikeLiked by 1 person