Some warships which survived WWII were given updates during the late 1940s or 1950s, for the most part modest changes to keep them current a while longer. In terms of being the most dramatically altered, a few examples stand out including the two WWII Baltimore class gun cruisers transformed into the US Navy’s first guided missile cruisers; USS Boston (CAG-1) and USS Canberra (CAG-2).

Of all WWII warships later rebuilt, Taiwan’s Wu Chin III modifications to Gearing class destroyers may be the most amazing. Unlike the cruisers above, the Taiwanese were packing more technology into smaller hulls; they did not have the Pentagon’s budget to play with; and most amazingly this was done not just years after WWII ended, but almost a half-century later.

(The Gearing class destroyer USS Power (DD-839) at the end of WWII.)

(The Wu Chin III-rebuilt destroyer ROCS Shen Yang – the former USS Power of WWII – in the 21st century.)

Gearing class: basic characteristics

Entering service during WWII’s final year, the American Gearing class was without question the best destroyer type of WWII and by late 1945 was perhaps the best all-around warship of any sort. Today it is still remembered as one of the best destroyer designs of all time, in any era. The Gearing class measured 390’5″ x 40’9″ x 14’3″ with a full displacement of 3,520t. As built during WWII there were three Mk38 twin 5″ turrets, smaller 40mm and 20mm AA guns, ten ship-to-ship torpedoes; along with depth charges, Mk6 K-guns, and Mk11 Hedgehog anti-submarine weapons. The Gearing class was fast (36½ kts), long-ranged, strongly-built, and designed from the start for radar.

(USS Hanson (DD-832) participated in the final months of WWII. It was later modified under the FRAM program, then fought in Vietnam, and still later sold to Taiwan. Decades after WWII it would be one of the Wu Chin III rebuilds.) (photo via navsource website)

a brief history of ROCN destroyers

Taiwan’s navy, the Republic Of China Navy (ROCN), is the legacy of the nationalist Chinese force which fought Japan during WWII and then fled the Chinese mainland to Taiwan after the communists won the civil war in 1949. For the majority of the Cold War era, the ROCN was almost top-to-bottom American WWII designs.

(ROCS Tan Yang, formerly the Imperial Japanese Navy’s IJN Yukikaze. Refitted with American guns and radars after WWII, this Kagero class destroyer was quite active in Taiwanese service, sinking a Chinese warship and capturing intact a Soviet tanker caught aiding the communists. ROCS Tan Yang decommissioned into reserve during 1966, was damaged by a typhoon in 1969 and scrapped several months later.)

After the Korean War ended Taiwan began a major naval revamping centered on an enlarged destroyer fleet. Taiwan imported WWII Benson and Gleaves class destroyers from the United States, starting in 1954.

(ROCS Nan Yang had been USS Plunkett (DD-431) during WWII. This Gleaves class destroyer served Taiwan from 1959 – 1975.)

These gun destroyers were good and got the ROCN back on its feet after the exile to Taiwan. However they were old and had no real prospects of being further modernized. During the late 1960s, another fleet change was made, centered on larger WWII US Navy destroyers: the Fletcher, Sumner, and Gearing classes. Deliveries began in 1967.

(ROCS Hsiang Yang, a Sumner class destroyer, had been USS Brush (DD-745) during WWII and a veteran of the Iwo Jima and Okinawa operations. It never received a FRAM upgrade in American service and was sold in December 1969. Above is its arrival in Taiwan in 1970, still using the ROCN’s “second” pennant number system. It remained a “straight (no modifications) Sumner”, decommissioning in 1984.)

This turned into a rolling effort which spanned the 1970s and 1980s, first with “straight”-configuration destroyers of these classes and then later, ones which had received major US Navy rebuilds (DER, FRAM I, FRAM II) prior to transfer.

(ROCS Liao Yang had been USS Hanson (DD-832). It had received the FRAM I rebuild while still in American use. It was later rebuilt again as a Wu Chin ship. Under the ROCN’s “third” and current system, destroyer hull numbers start with a nine.)

beginnings of the project

China’s disastrous “cultural revolution”, which ran from 1966 into the early 1970s, bought Taiwan’s navy some time as it stalled the PRC’s evolution in naval technology and in some areas, knocked it backwards. None the less, by the mid-1970s the PRC was again modernizing its navy; moving away from torpedo boats and gun patrol craft towards modern seagoing warships armed with missiles, backed up by modern strike aircraft.

A limited budget and Taiwan’s increasing isolation in the world arms market meant that the ROCN was more or less locked in to the WWII-vintage American warships it was using, at least for the short term.

In 1974 Taiwan’s Zhongshan Institute began a joint project with Kaohsiung Naval Shipyard and the ROCN, in a bid to extend the realistic usefulness of WWII destroyers. The effort was soon split into two paths.

Project “Fuyang” was to extend the physical lifespan of WWII hulls; the structural and machinery components.

Project “Wu Chin” was to modernize WWII-era destroyers for the type of sea combat which might be expected during the 1980s and 1990s. Wu Chin (“Weapon Improvement”) was an extremely complicated project. Rebuilds were supposed to begin during 1979 but the first Wu Chin I candidate did not enter the shipyard until early 1981.

(ROCS Heng Yang was formerly USS Samuel N. Moore (DD-747) during WWII. In June 1976 the aft twin 5″ gun turret was experimentally replaced by six Israeli Gabriel I missiles. It was the first Taiwanese warship with missiles of any type. Known as “Tien Shi”, this program did not give ROCS Heng Yang the other Wu Chin I upgrades. It was discarded in 1991.)

Wu Chin I

This was the original program. Rebuilds started in 1981 and ran through 1983. It could be applied to Fletcher, Sumner, or Gearing class hulls; in any (“straight” WWII, DER, FRAM I or II) starting status.

For Fletcher class destroyers (easily recognizable as they had single main gun turrets) three of the five main 5″ guns from WWII were removed along with the WWII torpedo tubes, if they were still aboard. Ahead of the bridge, an OTO-Melara 76mm gun was fitted. Aft, a RIM-72C Sea Chaparral quad launcher was fitted, along with “coffin” launchers for Hsiung Feng I anti-ship missiles. Two triple Mk32 tubes for Mk46 ASW torpedoes were installed, if they were not already aboard.

For the bigger Sumner and Gearing class destroyers selected for Wu Chin I, the fit was generally similar except that one or two of the three twin 5″ gun turrets from WWII was retained. On Sumner and Gearing hulls which had a hangar for the QH-50 DASH heli-drone in US Navy service, this was retained to fly a manned MD500 anti-submarine helicopter.

The sensor fits were greatly modernized but varied from ship to ship.

(ROCS Huei Yang, a Wu Chin I-rebuilt Sumner class destroyer. It had been USS English (DD-696) during WWII. This view shows the new 76mm gun forward and four-armed Sea Chaparral launcher aft.)

The results of Wu Chin I were a mixed bag. During the project’s concept phase, it was forecast that making the effort compatible with a variety of WWII American hulls would be beneficial financially, which would seem logical. Ten destroyers received Wu Chin I, therein being three different classes (Fletcher, Sumner, Gearing) in five different starting configurations. As it turned out this complicated the effort and made it more expensive. None the less it showed that the basic rebuild concept was viable.

Wu Chin II

Only four WWII destroyers were involved in this 1983 – 1986 effort. They were all Gearing class ships, however in different starting configurations. Wu Chin II sought to increase the new weaponry aboard, and also made utilization of imported Israeli systems and Israeli technical assistance.

In the final product, there were variations from one destroyer to another amongst the four, but overall it was considered successful.

(ROCS Dang Yang at sea in 1995, with the new 76mm gun and a triple launcher for Hsiung Feng I.)

limitations of Wu Chin I / II equipment

The Wu Chin I and II rebuilds were borne of urgency: Taiwan had to do something to keep ageing WWII destroyers competitive, and had to do it fast. To that end, the new weaponry installed was relatively simple.

The surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) were the RIM-72C Sea Chaparral system. This was a 1970s nautical offshoot of the US Army’s land-based MIM-72 Chaparral, which itself was a modification of the US Air Force’s AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missile.

(The four-armed RIM-72C launcher aboard a Wu Chin I or II rebuild.)

Although it was more effective than WWII-era AA guns, Sea Chaparral was not exactly a world-class SAM. The quadruple launcher on the Wu Chin I and IIs had a magazine with two reloads per arm, but the reloading was not rapid. The missile itself is infrared-homing, and the maximum range is 2¾ – 3 NM with a minimum of 200yds. That doesn’t allow for a particularly wide engagement envelope. Sea Chaparral offers self-protection to its host ship, but can not protect others in a task force nor deal with an advanced threat.

(A RIM-72C Sea Chaparral being fired from one of the Wu Chin I or II rebuilds.)

Sea Chaparral was good enough to quickly give the WWII hulls a modern self-defense against some Chinese air threats, but insufficient for what would be expected in the future.

The Hsiung Feng I ship-to-ship missile is similar to the Israeli Gabriel I and the South African Skerpioen. Like the Skerpioen, it was without doubt developed with Israeli assistance; in fact Taiwan bought fifty Gabriels to aid in its development and to fill launchers until enough were available. It is fired out of a “coffin”-like deck mount.

(The Hsiung Feng I’s launching “coffins” could be single, pairs, or triples and oriented fore or aft. This was a forward triple aboard a Wu Chin II rebuild.)

(Hsiung Feng I being fired.)

Hsiung Feng I had a maximum range of 21 NM and flew at Mach 0.65, with a 330 lbs HE warhead. Obviously, it was a more lethal naval weapon in the 1980s than WWII gunfire. It was designed in a time when a main Chinese anti-ship missile was the CSS-N-2 “Safflower”, a clone of the Soviet SS-N-2 “Styx”, which had a range of 45 NM but was usually limited to only 20 NM by the radar horizon. As such, Hsiung Feng I was an acceptable counterpart for the short term, but not a final answer.

Wu Chin III

area AAW

In naval lingo, “area AAW (anti-air warfare)” is a capability where a warship with longer-ranged radars and larger SAMs can protect not only itself against aircraft or missiles, but also other warships in a task force; and do so at longer ranges – preferably even outside of the attacker’s ordnance range. Multiple area AAW units in a task force are even better as this gives overlapping engagement arcs along with the ability to defeat saturation-style attacks.

Area AAW is neither simple nor cheap. Long range SAMs take up space and weight – their launchers, magazines, director radars – and use sophisticated electronics to function. This typically limits them to large frigates, destroyers, and cruisers.

In the 1980s, area AAW was the Taiwanese navy’s biggest shortcoming. The plan to address this was seven Cheng Kung class missile frigates (a license-built version of the American O.H. Perry class) followed by several Tien Tan class guided missile destroyers. But these would not start to enter service until the early 1990s and the last not until the new millennium. So there was an urgent gap to be filled, quickly but cheaply, somehow. Of this the Wu Chin III project began.

major reconstructions of WWII hulls

Outside the naval community, the systems of a warship are usually thought of as what the naked eye sees from the pier: above-deck gun barrels, missile launchers, and radar dishes. This omits the tremendous complexity below decks.

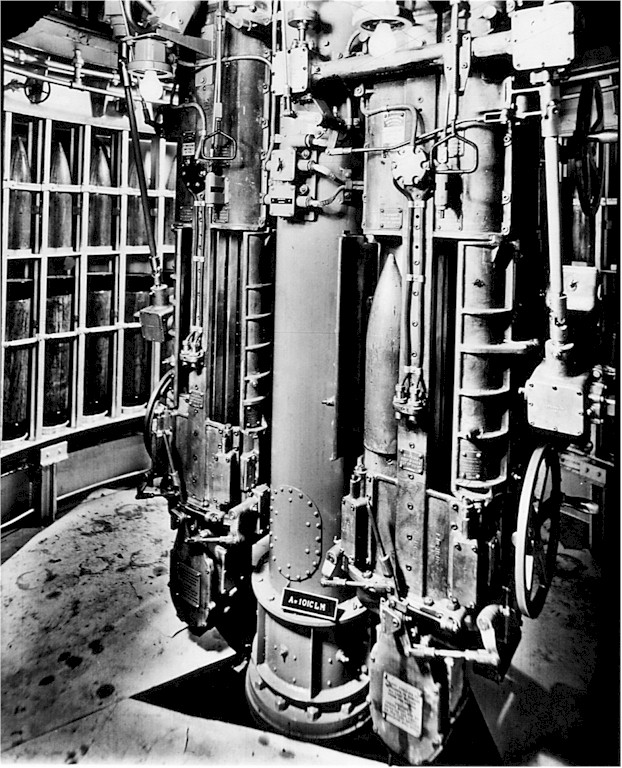

Replacing a WWII item, like the 5″ turrets, was not a “plug & play” thing. After the WWII item was completely extracted (including the below-decks magazine and rotation mechanisms), a large number of changes were needed.

(To illustrate, this was the 5″ gun magazine on a Gearing class destroyer during WWII.)

(…And its replacement aboard Wu Chin III-rebuilt Gearings, the OTO-Melara 76mm. Not only was the topside gun different but the below decks magazine had different height, diameter, layout, shape, and powering requirements.)

Using the above example (the 5″ to 76mm gun change) structural bulkheads would have to be cut, hydraulic lines capped off and rerouted (keeping in mind other upstream and downstream uses of that same line), electric wiring relaid and new transformers installed, even things like internal walkways and lighting changed.

The same went for radars: they were not just spinning dishes that could be slapped anywhere. They had to be sited in mast locations where they could be useful, but not mutually interfere with each other. Existing cabling trunks would have to be ripped out and relaid, new processor boxes sited below decks, and so on.

Through all of this, topweight and centre-of-gravity changes had to be tracked and managed. Modern naval systems are hungry for electricity, and the generative capacity of the ship had to be monitored as well.

(The final wiring map of ROCS Te Yang was a blend of WWII, FRAM I, and Wu Chin III.)

In the early days of naval SAMs, they were thought of as “a cruiser’s weapon”, too big for destroyer hulls. In 1955 the US Navy modified USS Gyatt (DD-712), a WWII Gearing class destroyer, with a twin-arm launcher for RIM-2 Terrier SAMs.

(The modified USS Gyatt.) (photo via navsource website)

(The modified USS Gyatt.) (photo via navsource website)

The partially-successful experiment showed the US Navy that area AAW weaponry could in fact be used on destroyers, but, that modifying existing WWII-era hulls was probably the wrong way to go about it. There was simply not enough room and displacement, and the changes were too many. USS Gyatt later reverted back to a gun configuration.

Now a third of a century later, this would be what the Taiwanese navy would attempt.

basic parameters of the project

The first thing decided was that Wu Chin III would be a total rebuild. Wu Chin I & II were major efforts, but still retained some WWII systems. Wu Chin III would eliminate every single remnant of WWII and in fact, the only onboard systems at all which would be retained would be the FRAM-era anti-submarine weapons; this being as they were already the top tier available to Taiwan at that time – there was nothing newer to replace them with.

The second thing decided after experiences with Wu Chin I & II was complete standardization. There would be no “here-‘n-there” differences. The starting configuration would all be Gearing (FRAM I) ships, and all would be rebuilt to a common design.

While area AAW would be the focus, these would emerge as true multi-mission destroyers, capable of ship-to-ship or anti-submarine (ASW) combat.

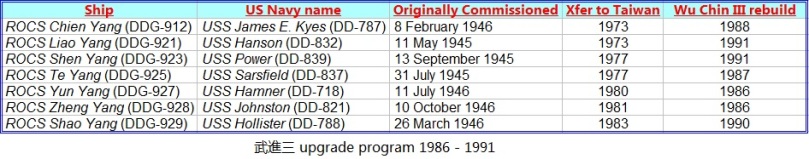

destroyers selected

An eighth ship, ROCS Lao Yang, was part of the Wu Chin III plan but scrubbed after it ran aground in 1987.

As mentioned, all were Gearing class which had received the FRAM I update while in US Navy service. All were WWII construction, but only three commissioned before WWII ended.

(Wu Chin III rebuild in progress; here the shipyard is installing the radome for the W-160 radar atop the aft mast.)

Each rebuild took about 26 weeks which was not very long, considering the huge amount of changes made.

WEAPONS

1) OTO-Melara 76mm 2) Mk32 tubes 3) RIM-66 Standard 4) RUR-5 ASROC 5) Hsiung Feng II 6) Bofors L/70 40mm 7) Mk15 Phalanx CIWS 8) helipad & hangar for MD500

surface-to-air missiles

Area AAW was the focus of the whole Wu Chin III project, and the weapon selected was the American RIM-66 Standard SAM.

(Standard being fired from ROCS Te Yang, the ex-USS Sarsfield (DD-837) of WWII.)

The version of RIM-66 Standard used here was SM1-MR (RIM-66B/E). It had a range between 18 – 40 NM depending on the target’s altitude, with 29 NM being a typical maximum. Standard flew at Mach 3.5 up to 80,100′. It had a 137 lbs HE-FRAG warhead. RIM-66 used semi-active radar homing; by this the missile’s seeker homed in on radar energy reflected off the target from a transmitting radar (the “illuminator”) aboard the destroyer.

(Standard being fired from a Wu Chin III destroyer’s forward port bank of box launchers.)

Taiwan purchased 170 Standard missiles as part of Wu Chin III. This was sufficient to give each destroyer two full loadouts plus four or five exercise shots per ship. The average export cost per missile in the 1990s was $659,000 ($1.06 million in 2021 dollars).

“SAMs-in-a-box”

Normally, RIM-66 is fired from either a proper one- or two-armed rotating and elevating launcher, fed by an automated below-decks magazine. For Wu Chin III this would be impossible as the WWII Gearing hull’s size and shape simply precluded that.

“SAMs-in-a-box”, more properly “firing deck encapsulations”, have been used with area AAW missiles by a few navies. In all instances, it was basically because there was no other option available. For example, Iran used RIM-66 in boxes aboard WWII Sumner class destroyers for the same reason as Taiwan’s Gearings; because no proper launcher could possibly fit aboard.

(The Taiwanese-made single-shot box launcher. The missile broke through a frangible muzzle closure.)

On Wu Chin III ships there were ten: two sets of two firing crossdeck ahead of the bridge, and aft two sets of three, facing either port or starboard.

(The forward twin SAM boxes aboard ROCS Shen Yang. The port side ASW torpedo tubes are also shown.)

(One of the two aft triple sets aboard the same destroyer. The hull’s C-ring with three braces is a WWII object, it was to keep tugboats clear of the propeller’s spin disc. Judging by the bends and dents on it, this had been necessary over the decades.)

Comparing pro’s and con’s, the negatives are obvious. Single-shot decktop box launchers greatly limit the number of SAMs carried: one normal Mk13 launcher for RIM-66 has a 40-round below-decks magazine, while the Wu Chin III ships carried only 10 boxed SAMs total shipwide. They consume a great deal of deck “real estate” in terms of square feet per missile, which limits other weapons the ship can carry. The boxes can only be reloaded pierside.

(A box launcher being craned aboard a Wu Chin III ship.)

While a Standard does not need to be “aimed” like a gun, it must be reasonably oriented at the target’s general direction when fired. A normal launcher would just rotate to whatever bearing the target is at. But since “SAMs-in-a-box” are fixed, this becomes a problem. Against aircraft approaching broadside, at least three but no more than half of the ten missiles would be instantly usable. On an oblique approach, as few as two might be usable without the ship having to maneuver; and there was a zone astern where none could engage without the destroyer changing course.

There really aren’t a lot of positives, other than nothing else would work. Some good points are that box launchers are cheap and require almost zero maintenance.

(RIM-66 Standard being fired from a Wu Chin III-rebuilt destroyer’s starboard aft launcher.)

The value to the Taiwanese navy was tremendous. For the first time ever, the fleet had a true area AAW ability. In less than two decades the ROCN jumped from old visually-aimed WWII AA guns to a modern, high-performance SAM; all without new hull construction.

guns

The new main gun was the OTO-Melara 76mm. This was a successful Cold War shipboard gun. Designed in Italy, it was used around the free world, and by the 1980s was one of the most common things seen on all seas. In the US Navy and US Coast Guard, it is designated Mk75.

(OTO-Melara 76mm gun aboard ROCS Yun Yang)

(OTO-Melara 76mm aboard ROCS Shen Yang. The topside mount itself is unmanned; the small hatch is for maintenance and clearing jams.)

This modern gun fires 76mm ammunition with a 13¾ lbs projectile. It is water-cooled and has a 80rpm rate-of-fire. The below-decks magazine holds 80rds. It can be fired against ships or aircraft. The accurate effective range is 4¼ NM with a 9 NM ballistic maximum. The topside “turret” (technically incorrect as it is unmanned) rotates at 60°/sec. It is unarmored but rated to a 7psi overpressure.

The OTO-Melara 76mm was already in use aboard the Wu Chin I and II rebuilds, so there were no issues integrating it into Wu Chin III.

(ROCS Shen Yang around the turn of the millennium showing the new 76mm gun, plus the ASW torpedo tubes and forward SAM launchers.)

(The same destroyer in May 1980, showing the Mk38 twin turret of WWII still in place then.) (photo via Chen Chang Fu)

Aboard the rebuilt Gearing class, this gun replaced the forward Mk38 twin turret for the 5″ Mk12 gun. The new OTO-Melara 76mm had half the range of the WWII 5″ weapon and fired a smaller shell, but had a rate-of-fire nearly tripled and with its modern fire control system, could be expected to score hits with the first or second rounds. Comparing complete setups (guns, turrets, mechanisms, magazines, and ammunition) the new weapon was nearly 10x lighter.

The secondary armament was a pair of Bofors L/70 40mm guns. When Wu Chin I was still in early discussions, this had been considered as an alternative to the OTO-Melara 76mm as a main gun, as the latter was expensive. Now for Wu Chin III, they were just added along with it to beef up the destroyer’s short-range gunfire against aircraft or ships.

This gun had an effective range of about 2½ NM. Both it and its 40mm ammunition were license-made in Taiwan. The weapon is inside a fibreglass enclosure big enough for three or four crewmen. It was desirable to aim the L/70 via an off-mount radar.

Aboard Wu Chin III ships, the L/70s were sited asymmetrically. The starboard was on an amidships elevated balcony, and the port more aft, a deck level lower in an alcove next to the helicopter hangar.

(The starboard 40mm of ROCS Chien Yang firing. This had been USS James E. Kyes (DD-787). This photo also shows the new starboard side jammer above and behind the gun, and the four muzzles of the anti-ship missiles at lower right.)

(The port side 40mm on the same ship.)

The final new gun was a Mk15 Phalanx CIWS (close-in weapons system). It is a 6-barrelled, gatling-type 20mm gun with a 3,000rpm rate-of-fire and a 989rds magazine; intended to shoot down incoming missiles. Completely automated, it has two radars, one which tracks incoming anti-ship missiles and the other which tracks outgoing rounds, with a computer then correcting the aim until the two tracks meet.

(Phalanx aboard ROCS Shen Yang.)

Aboard Wu Chin III ships, the Phalanx was bolted onto a new deckhouse aft, inbetween the two triple SAM boxes.

(Phalanx aboard a Wu Chin III ship engaging a target drone during an exercise.)

There was a roughly 50° wedge forward unprotected. This was unavoidable, as the WWII Gearing hull simply precluded adding a second CIWS or locating the existing one in a spot with full coverage.

(ROCS Zheng Yang at sea. The Phalanx could fire over corners of the helipad if needed but obviously not fully forward.)

Phalanx was a tremendous self-defense asset to the Wu Chin III destroyers. During the 1990s, there were many warships worldwide still lacking a CIWS effective against modern anti-ship missiles. To have one on rebuilt WWII hulls was a bonus.

ASW weapons

All anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weaponry involved with Wu Chin III was already onboard from the Gearing FRAM I modification. Any remaining WWII ASW kit (Hedgehogs, depth charges) was removed if it had not already been so.

ASROC

RUR-5 ASROC was a surface-to-sub missile. The payload was a Mk46 acoustic-homing torpedo which separated off the missile portion. ASROC had a range of 6 NM in the air and the detached torpedo could travel some distance on its own in the water. The RUR-5 missile was fired from a Mk112 “pepperbox”; this rotated to the target submarine’s bearing and elevated one of the four over/under twin cells 45° for firing.

(ROCS Shen Yang in 2005 with one of the Mk112’s twin cells elevated.)

The theory of ASROC was that if a destroyer used normal ASW torpedoes, these took time to travel to the target submarine, during which the sub would undoubtedly hear it coming and take evasive action, deploy countermeasures, or counterfire its own torpedo down the incoming weapon’s bearing towards the destroyer. ASROC plopped a torpedo nearly directly on top of the target submarine, giving it little chance to react. The missile also extended the ship’s ASW engagement range further out.

(ASROC exercise in the early 1990s, before the Hsiung Feng II missiles were installed on this Wu Chin III ship.)

The FRAM I refits done to Gearings while they were still US Navy ships had a reload magazine in a deckhouse forward of the aft superstructure. The Hsiung Feng II missiles, when added to the Wu Chin III ships, blocked the reloading area so the Taiwanese destroyers lost reload capability. This was considered acceptable, as the RUR-5s were expensive and Taiwan had a limited number in inventory to begin with.

(The four anti-ship missiles, to the far left, blocked off the ASROC reloading area.)

torpedoes

The unguided Mk15 ship-to-ship torpedoes which the Gearing class carried during WWII were already long gone off these destroyers by the time Wu Chin III started.

During WWII the “B” position, the elevated deck ahead of the bridge, seated a twin 5″ gun turret. This had already been eliminated in the United States during the FRAM I upgrade and replaced by two triple Mk32 ASW torpedo tubes. For Wu Chin III, the forward “SAMs-in-a-box” were put here but in a way that they fired clear of the Mk32 tubes as seen below.

These tubes fired Mk46 homing torpedoes, a quarter-ton weapon moving at 40 kts with a maximum depth of 1,200′. Their maximum range was 5 ¾ NM.

For Wu Chin III, these torpedoes backed up ASROC in the ASW role. Basically they were already onboard these seven ships, weren’t getting in the way of anything else, and were modern and useful; so there would have been no point to removing them.

helicopter

In the United States, WWII Gearing class destroyers which received FRAM I had a mini-hangar and small helipad added for the QH-50 DASH heli-drone, which Taiwan never used.

Taiwan instead adapted these small facilities for a manned helicopter, the MD500, a descendant of the US Army’s OH-6 Cayuse of the Vietnam War.

This little 2-man helicopter could carry a Mk46 torpedo, or two depth charges, or a machine gun. It was fitted with a RDR-1300 surface search radar and a AN/ASQ-81 magnetic anomoly detector (MAD). The MAD was towed in the air behind the helicopter, and detected submerged steel objects (like a submarine) directly underneath it. The MD500 had a combat radius of only 104 NM when carrying a torpedo. The skids had inflation bags for emergency water landings.

The MD500 was not an ideal ASW helicopter. Normally, an ASW chopper uses its MAD only as a backup to dunking sonar or sonobuoys, but there was room for neither on the little MD500 so a MAD was the only option. The helicopter’s searching time was limited by its small combat radius. But for the Wu Chin III ships, there was no other choice. Taiwan’s other naval helicopter, the SH-60 Seahawk (which Taiwan calls S-70C Thunder Hawk) was way too big for the WWII destroyers. The MD500s still offered some use, in that an enemy sub within sonar range but outside ASROC range could be quickly attacked.

Taiwan has a limited number of MD500s and they were used around the fleet, so the Wu Chin III ships did not always sail with one aboard.

anti-ship missiles

The final weapon added to the Wu Chin III ships was the Hsiung Feng II ship-to-ship missile.

(Hsiung Feng II firing off a Wu Chin III-rebuilt WWII destroyer.)

During the early 1980s, Iraq and Argentina made devastating use of the French-made Exocet missile. Taiwan sought a similar capability (either Exocet, Harpoon, or Otomat) for their WWII destroyers but was foiled by Chinese diplomatic pressure on their origin countries or (with Harpoon) American political reluctance. Therefore the Chung-Shan Institute (NCSIST) was tasked to develop a similar missile from scratch. NCSIST had its work cut out for it, as only a handful of nations had successfully fielded a missile like Exocet at that time.

In what must have been a tremendously expensive endeavor, this was completed in the late 1980s. Despite its name, Hsiung Feng II has nothing to do with the small Hsiung Feng Is carried on the Wu Chin I & IIs. The name was probably a security ploy. Prototype missiles were tested in secret around 1986 – 1987 and it was unveiled in February 1988.

(Hsiung Feng II impacting a decommissioned WWII tugboat.)

Hsiung Feng II is 15’9″ long and weighs 1,510 lbs. It has a 407 lbs HE warhead. This missile has a drop-off rocket booster and an air-breathing jet engine, and travels at 563 kts which at its attack altitude equates to Mach 0.85. The maximum range is between 75 – 86 NM depending on its attack profile. Hsiung Feng II is guided by an active radar seeker; it also has an infrared “eyeball” (which can be seen atop the missile’s nose in the above photo) which activates if the seeker is being jammed, then homing in on the target’s heat. Once fired, no further action is required by the destroyer.

Aboard the Wu Chin III ships, Hsiung Feng II was fired from a fixed 4-round launcher amidships behind the ASROC “pepperbox”.

(Three different views of the quad launcher aboard Wu Chin III destroyers.)

As mentioned already, the launcher unavoidably blocked off the ASROC reload magazine, which was accepted. The launcher was fixed facing starboard; this obviously meant that a maneuver would be required to engage ships on the port side. There was no other option with the WWII hullform and again, this limitation was accepted.

Development of this project was not synced with the overall Wu Chin III timeline. As the focus was area AAW, not surface combat, the decision was made to get the seven destroyers rebuilt and add Hsiung Feng II as it became available. Some of these ships operated for a time without it.

(ROCS Liao Yang in the early 1990s, with the space for the quad launcher still empty.) (official US Navy photo)

Hsiung Feng II was a remarkable achievement for Taiwan’s defense industry and a powerful weapon to put on these refit WWII destroyers.

SENSORS

The electronics carried aboard the Wu Chin III-rebuilt destroyers were every bit as important as the new weapons. Integrating them onto a WWII hull was equally challenging as the new weapons, if not more.

1) AN/SQS-23H 2) STIR 3) navigation radar 4) AN/SPS-10 5) DA-08 6) AN/SRN-15 TACAN 7) CR-201 launchers 8) ESM 9) Westinghouse W-160 10) Chang Feng III ECM 11) Fanfare towed noisemaker

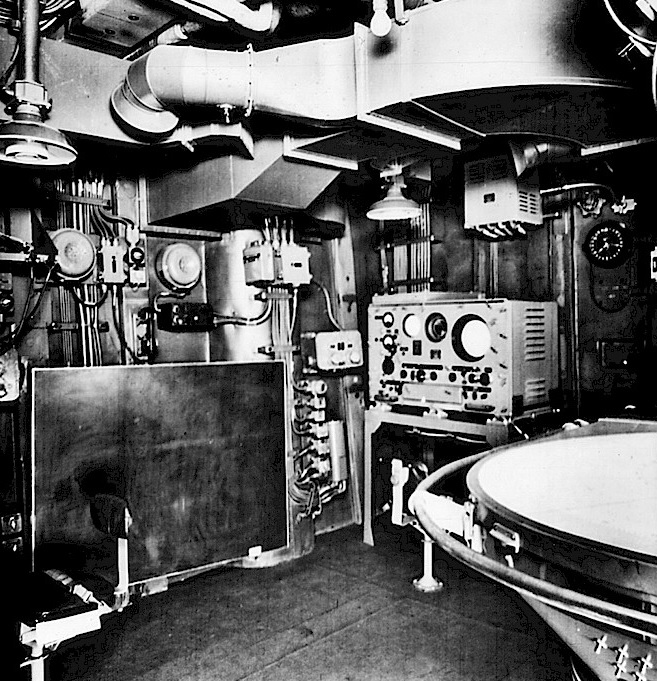

As built during WWII, the Gearing class was one of the first destroyer types in the world with a primitive Combat Information Center (CIC). The CIC, deep inside the ship, is the “battle brain” of the destroyer, where all the sensor data, radio information, and weapons are tied together. Already by the end of WWII, the CIC was replacing the bridge as the spot onboard where battles were commanded.

(The CIC of Sumner & Gearing class destroyers during WWII.) (photo via navsource website)

(The CIC of a Wu Chin III-rebuilt Gearing in the 21st century.)

The CICs of these seven destroyers were gutted and refilled with the latest computers, control consoles, and communications gear. Honeywell developed a digital combat computer system which could track 24 targets and simultaneously attack 4 of them. Any legacy electronics from FRAM I left aboard were routed through a digital-analog computer. Any WWII-era processors or displays still aboard were simply removed.

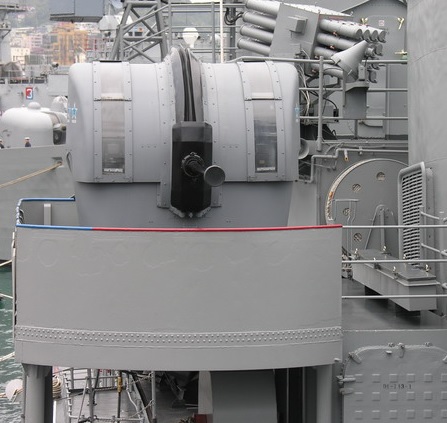

Perhaps the most important sensor aboard was the Separate Target Illumination Radar (STIR). It illuminated target planes and missiles with radar energy for RIM-66 SAMs to then home in on. It was mounted above the bridge, where the fire controller for the 5″ guns had been during WWII.

A modern area AAW destroyer or cruiser has two, three, or even four illuminators but on the WWII Gearing hull, there was only room for one. The drawback was that the Wu Chin III ships could only have a single SAM in terminal homing at a time. The Wu Chin III ships also used STIR as the fire control radar for the new 76mm gun; to that end the ship could not simultaneously use the main gun and SAMs.

The STIR also had an electro-optical device ahead of it. If the radar was being jammed or was destroyed, this could provide gunnery control for the 76mm weapon out to the visual horizon.

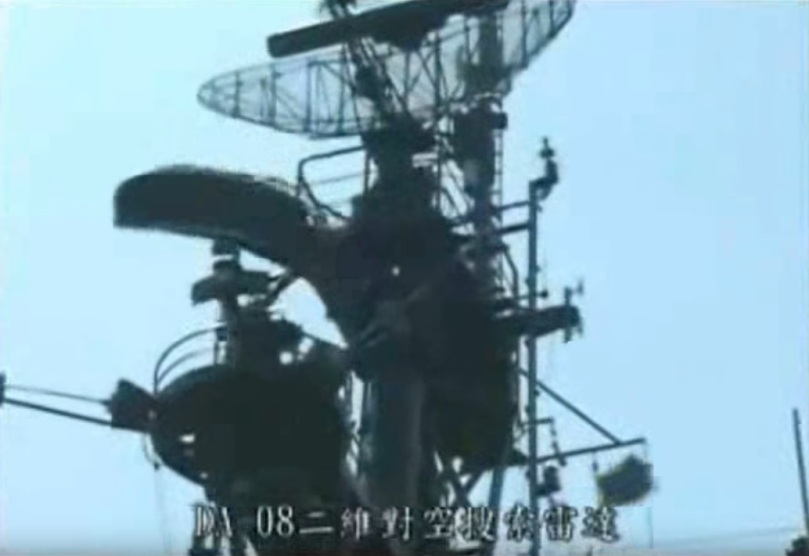

(DA-08 with AN/SPS-10 beneath it.)

On the mainmast, a small Taiwanese navigation radar was installed. Above it, the AN/SPS-10 surface search radar was mounted. By the late 1980s this was not really cutting-edge anymore, but Taiwan liked AN/SPS-10 as it was very reliable and was already pre-existing in the country, eliminating an import hassle. AN/SPS-10 also had a knack for finding small things near the ocean’s surface, and the ROCN estimated it useful for detecting inbound sea-skimming missiles.

The main radar, set above AN/SPS-10, was the Dutch-made DA-08 air search and track radar. During the 1980s China applied immense diplomatic pressure on the Netherlands to stop selling arms to Taiwan, and importing these radars was a big hurdle. The processors and computers were all new, but Taiwan reused old DA-05 external antennas, to make one less thing the Dutch would have to hassle with the Chinese about. Surprisingly they apparently worked fine.

At the top of the mainmast (the highest point aboard) was a AN/SRN-15 TACAN. This was a radio beacon for the helicopter to find the ship.

The aft mast was for the W-160 radar. A private-venture design by the American company Westinghouse, this project started in the early 1980s as an idea to adapt the F-16 Falcon fighter jet’s AN/APG-66 for other uses. As Wu Chin got underway, Taiwan issued a fixed-price contract to Westinghouse to field it aboard ship, which was not an easy task.

(W-160 on the aft mast, with the unrelated ESM thimble above it and Phalanx in the foreground.)

Aboard Wu Chin III destroyers, W-160 provided fire control for the new 40mm guns. It was sensitive enough that the Taiwanese also regarded it as a backup for any other radar onboard. Westinghouse claimed that with some add-on modules, it could also be a backup to STIR as a RIM-66 illuminator. It is unknown if Taiwan added these.

Westinghouse later unsuccessfully pitched this radar to Portugal. Surprisingly just before the Tiananmen Square incidents of 1989, China itself showed interest in buying the W-160, which of course never happened.

The electronic warfare suite of the Wu Chin III rebuilds was astonishing. The main component was the Chang Feng III jammer. This was a pair of polygon-shaped radomes aside the aft superstructure.

Chang Feng III was an electronic countermeasures (ECM) system. It had two uses, the first being to simply broadcast a barrage of electromagnetic “garbage”, blinding a whole frequency. The second (and quite remarkable for a navy like Taiwan to possess in the early 1990s) was to deceptively produce a radar-offset “image” of the ship, so that an enemy aircraft radar or missile’s seeker would have to guess which was real.

Besides being far and away the highest-tech item aboard, Chang Feng III was also the most eyebrow-raising. It was supposedly developed by NCSIST “…in cooperation with” the American company Hughes. In fit, form, function, and even to a degree physical appearance, Chang Feng III strongly resembles Hughes’s AN/SLQ-17. It is very widely believed that NCSIST just imported the Hughes design wholescale and slapped its name on it, to avoid a trifecta diplomatic hassle between China, Hughes, and the US Congress.

Chang Feng III also had a passive (ESM) “thimble” atop the W-160’s mast. It alerted the destroyer to enemy radars in the area and their bearing.

This was an astonishing piece of technology for Taiwan to field in that era. It was above and beyond anything in the Chinese fleet at the time and would rank with Soviet and American ECM systems. To have it on WWII-era hulls is all the more remarkable.

Four sixteen-barrelled CR-201 countermeasures launchers were carried. These fired 126mm rockets with a payload of chaff. Developed during WWII, chaff was originally just thin strips of metal foil dropped from a warplane to blind German radars. By the 1990s, it was well-refined but the basic idea remained the same. A typical tactic for the CR-201 would be to fire a volley at short range, creating a chaff “bloom”. To an incoming missile this turned the destroyer’s radar profile into a shapeless blob, hopefully causing the missile’s seeker to break lock. The launcher itself reused a failed entrant into the Taiwanese army’s Kung Fen artillery competition.

These seven ships already had AN/SQS-23 active/passive sonar onboard. As part of FRAM I, this had replaced the WWII sonar gear. A team from Honeywell upgraded it to AN/SQS-23H standard but otherwise the Wu Chin III rebuild just left it alone.

(ROCS Liao Yang in drydock showing the AN/SQS-23H. This was about the largest practical size of sonardome that could be refit onto a WWII destroyer.) (photo by Alex Wu)

hull

One thing that Wu Chin III did not change was the basic ship itself. The four Babcock & Wilcox boilers, and two General Electric geared steam turbines of WWII were all retained in the engine room along with a lot of pumps, machinery, and other miscellaneous equipment shipwide. Taiwan claimed the Wu Chin IIIs still had a maximum speed of “30+kts” with unofficial sources stating 31 kts, meaning that the WWII boilers and engines had only lost 5½ kts over 50 years.

(The main steam throttle board in the engine room was little changed from WWII.)

When analyzing the astonishing technological changes in the Wu Chin III program, it is easy to forget that the basic WWII Gearing hull is an extremely tough design which could absorb a lot of battle damage.

Wu Chin III ships in service

By the summer of 1991, all the refits were completed and less the anti-ship missiles, all seven Wu Chin III destroyers were in active service.

(One of the seven Wu Chin III ships being refueled at sea.)

(A Wu Chin III-rebuilt Gearing in the distance, operating with a Wu Chin I-rebuilt Fletcher in the foreground. The latter still retained its aft 5″ gun and depth charge rack from WWII.)

All received one refit during their post-rebuild careers. This installed the anti-ship missile quad launcher, and also added the new Ta Chen datalink. This allowed them to share targeting information between themselves and newer units in the ROCN. At least one (ROCS Shen Yang) also received M2HB Browning .50cal machine guns.

These ships mostly operated as part of the 131st Destroyer Squadron out of Keelung or 146th Frigate Squadron out of Magong City. They were extremely active, both in regular patrols of Taiwan’s sea space and foreign visits, as far away as South Africa and Indonesia.

keeping them going

In service the biggest maintenance challenge was not the new high-tech items, but rather keeping the WWII Gearing class hulls themselves running.

Shipwrights use a calculation called MTBF (mean time between failure) to predict how often things aboard a warship will break. For most of a warship’s expected lifespan, this is usually accurate. When warships are old, MTBF estimates begin to falter, as things fail more frequently at irregular intervals. When warships are very, very old (the Wu Chin III candidates were nearly a half-century old before work even began) it becomes little more than a guess.

Of the Wu Chin I destroyers, the Sumner class ROCS Hua Yang (ex-USS Bristol (DD-857) of WWII) had severe mechanical problems and decommissioned in 1993 having given less than 10 years in the rebuilt configuration. ROCS An Yang, a WWII Fletcher class, followed in 1997, also having mechanical challenges. The lessons learned from Wu Chin I were useful with keeping the II and III rebuilds operational longer.

One way the Wu Chin III ships were kept sailing into the new millennium was via stripping parts off other American WWII destroyers in the ROCN. First this was unmodified ships. Taiwan’s last WWII destroyer not to receive any of the three Wu Chins was ROCS Yueh Yang, formerly USS Haynsworth (DD-700) of WWII. It decommissioned in January 1999.

The remaining Wu Chin I rebuilds left service in 1999 and 2000. They were methodically stripped of anything useful for the Wu Chin III ships.

(The ex-ROCS Fu Yang, a Wu Chin I Gearing rebuild, was stripped of any usable spare parts between 1999 – 2003 and then sunk as a torpedo target.)

In 2000, the four Wu Chin II rebuilds left service. They too were then stripped of any spare parts that could be used on the Wu Chin IIIs.

(After ROCS Dang Yang, a Wu Chin II, left service the ship was stripped clean of anything useful and then scuttled as an artificial reef.)

Cannibalization is not a perfect answer. Things aboard a destroyer don’t break at equal rates. Oil hoses, blower motors, and pressure switches fail more often than say, the anchor or a door. Once a cannibalization hulk runs out of frequently-needed things, it really doesn’t matter what else remains. But by the start of the 21st century, spare parts for WWII boilers, condensers, and pumps were not exactly easy to come by, so it was an option.

end of the road, and was it all worth it?

(ROCS Shen Yang in the early 2000s.)

When Wu Chin III started, the success/failure threshold was 10 years of usefulness after refit, with an expectation of 13 years, and an upper realistic target of 15 years or slightly more.

To that criteria, the project was a success. The post-rebuild lifespans ranged between 14 – 16 years.

These ships were effective, if not perfect, throughout that timespan. Whatever the hull age and compromises involved, no navy on earth in the late 1990s would thumb its nose at an area AAW-capable destroyer, especially one also with an advanced ECM suite, a helicopter, long-range anti-ship missiles, a CIWS, and standoff ASW weapons.

The total cost of Wu Chin III is hard to calculate as because of Taiwan’s political situation, a lot of arms deals are done as “private sector” between parastatals and foreign firms. For certain, it was not cheap and a ton of money to spend on WWII-era hulls. As it turned out, it was a wise gamble. The Cheng Kung class frigates came in over budget and slightly behind schedule. The follow-on Tien Tan project was cancelled before even being started. So without these seven SAM-capable ships, however limited they were by “SAMs-in-a-box”, there would have been a hole in the ROCN’s air defenses for years.

The biggest factor to retiring these ships was time. The Gearing hulls and engines, by now 55 – 60 years old, were walking a tightrope and could have a major mechanical failure at any time. It made more sense to discard them in an orderly scheduled way.

China’s naval buildup was relentless in both quantity and quality. In the early 2000s Taiwan reasoned that by the late 2010s, a ship with just ten SAMs and one illuminator would be overmatched much like the Wu Chin Is with Sea Chaparral had been by the late 1990s.

Finally, a law passed by the civilian government capped the fleet at 24 active-duty destroyers and frigates at any moment, making the decision all the more easy.

The first to decommission were ROCS Shao Yang and ROCS Yun Yang in 2003. Three more followed in 2004, and then ROCS Zheng Yang in 2005. By the autumn of 2005, ROCS Shen Yang was the last at sea. It ceased making patrols in November 2005 and formally decommissioned on 1 January 2006. It was not only the last Wu Chin III Gearing, but the last WWII American destroyer of any class in any configuration in Taiwanese service. With it, an era that began in 1954 came to an end.

(When Wu Chin I was first being considered in the 1970s, Chinese naval aviation was still using the clumsy H-5 “Beagle”, a clone of the USSR’s obsolete Il-28 “Beagle” bomber. By the time of Wu Chin III, China was flying the JH-7 “Flounder”; a supersonic, agile naval strike jet armed with anti-ship missiles. It is fortunate the Taiwanese planned ahead.)

Of the decommissioned Wu Chin III Gearings, two were scrapped in the 2010s, two were turned into artificial reefs, and two were sunk as target hulks. One, ex-ROCS Te Yang, is preserved as a museum ship. However in a final oddity, most of the Wu Chin III equipment was stripped off it and replaced ad hoc with “incorrect leftovers”, like single WWII 5″ guns from a scrapped Fletcher and coffin launchers from a Wu Chin II.

Parts of these ships live on. The “SAMs-in-a-box” and STIR radars were moved onto the newer Cold War-era Knox class ASW frigates which Taiwan bought from the USA, under project “Wu Sanhua”. The light guns were transplanted onto new patrol ships. The anti-ship missiles were used as additional reloads for new frigates, and the electronics were available as spare parts.

(The Cold War-era Knox class frigate ROCS Lan Yang, formerly USS Joseph Hewes (FF-1078), in 2015 after receiving transplanted “SAMs-in-a-box” to give it an anti-aircraft capability. The warship in the foreground, ROCS Ta Han, had been USS Tawakoni (ATF-114) during WWII and finally decommissioned in November 2020.)

Obviously no WWII Gearing will ever be rebuilt again; Mexico decommissioned the last of the class in 2014.

Honestly it’s possible that there will never be such a warship reconstruction this elaborate and drastic again, of any type, ever. Modern warships are “life-cycled”, designed to a certain technology level with a planned lifespan. A navy builds it, runs the daylights out of it, gives it a modest mid-life refit, runs it hard again, and then junks it. Nobody can predict the future but it is difficult to imagine an Arleigh Burke or Udaloy destroyer still around in the 2060s and being rebuilt this drastically in a foreign fleet.

Wu Chin III was a product of a blip in time: the availability of the excellent WWII Gearing class hull as a canvas, Taiwan’s budgetary and political predicament, an urgent need in the fleet, and the technological skill to pull it off. These seven ships speak well of the Taiwanese engineers who did it, and the American shipyard workers of WWII who built the Gearing class.

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.

LikeLike

I served on the Moore DD-747, a Sumner, when it was decommissioned to sell/give to Taiwan. At the same time, about June, 1969 Taiwan also took the Brush DD-745. Both were never modernized except for 3″ aa twins, they still had CIC one deck below the bridge and the bridge was original except for the added outer bridge windows and overhead. The Fram conversion put CIC right behind the bridge with 2-3x more space. Taiwan probably got well running ships. I was on DD-754 that went through a overhaul in 1968. Lots of steel structure was replaced in places like under the boilers. In an overhaul the boilers got new tubes and bricks, lots of new steam piping, almost every motor and generator was rebuilt by the yard. The props, shafts and rudders pulled. New bearings, seals, etc. 754 got rebuilt gun mounts, new barrels, etc. Steering motors and hydraulics rebuilt. Radar antennas rebuilt as were the radar repeaters, gyro and repeaters, radios, antennas, and so on. Overhaul happened every 4 years. You name it, almost any machinery was removed and rebuilt. Even the clocks. I never heard of a Fletcher, Sumner or Gearing breaking down or not meeting it’s schedule. The navy must have saved a ton of money when they went to gas turbines. On a steam destroyer, about a third of the crew were engineers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When I was a kid, a magazine published the news of the retirement of the Shenyang. The title at that time was (The Withering of Asia’s Largest Destroyer Fleet). More than ten years have passed, thank you for writing this project in detail.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I served in the US Navy in the mid-1990s; it was strange to see Gearings and Ticonderogas at sea at the same time.

LikeLike

My first ship USS Hamner DD718 went to Taiwan and I was told after serving out the rest of her useful life there . . . became a sub target. I hated hearing that . . . but I will long remember the good times we had on her.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Wu Chin III: Taiwan’s remarkable rebuilt WWII destroyers — wwiiafterwwii […]

LikeLike

A question; why didn’t ROCN try a rotating box launcher for SAM, like Mk-16 ASROC one? As far as I knew, at least anti-surface versions of SM-1MR (RGM-66E/G) were compatibe with “matchbox” type launchers. Adding one octuple Mk-16 on the stern would likely not be much heavier than two dual and two triple fixed box launchers.

Considering that Mk-16 could fire both SM-1MR and ASROC, maybe the most practical solution were to move the amidship Mk-16 launcher on the stern, providing it with single-reload capability. It would allow to have, say, a mix of four SM-1MR and four ASROC constantly loaded and ready for all kind of action.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wondered that too. The only thing I can think of is that the USA wouldn’t sell the snubber swapout for inside the pepperbox to switch it from Asroc to Standard. The other thing is that every cell in the launcher switched is one fewer ASW round, so at the end you’d end up with, say, just four SAMs and four Asrocs instead of a larger number of both.

LikeLike

Was the topweight reduction the main reason the Taiwanese replaced the 5” with the 76mm gun? The rate of fire in the latter was higher sure, but it seems like the gun’s range being half that of the 5” would make it more dangerous to use in practice (i.e. making the destroyer even more vulnerable to return fire). And that’s not even counting the much lighter shell, like you mentioned.

Went from hefty to wimpy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No they considered the range difference largely irrelevant. The OTO-Melara 76mm can be electronically slaved to the new digital fire control system. The WWII gun was linked to the FRAM fire control system (I think it was the Mk67 or Mk68) but only in the sense that it laid in a solution, somebody in the turret had to traverse / elevate it to match that. The Taiwanese viewed all the guns mainly as AA assets and rate-of-fire and how quickly it could bear on target were more important for that.

LikeLike

Maybe someone could help me with the question – what exactly is Taiwanese “Te Yang” destroyer?

https://museumships.us/taiwan/te-yang

They claim it to be Gearing-class, a former USS Sarsfield (DD-837) – but it’s kinda clearly have Fletcher-class single 5-inch mounts. Also it doesn’t have indications of “Wu Chin III” refit. In fact, the only non-FRAM equipment I could see is three “Hsiung Feng I” missiles in front of superstructure.

On the other hand, she have ASROC and DASH deck, which weren’t installed both on Fletcher-class FRAM.

So… what the hell is she? The only plausible explanation I could invent is that it’s some FRAM Gearing, that was stripped of all armament, and while turned into museum – for some reason, fit with spare turrets from Fletcher-class ships.

LikeLike

It is mentioned in the article, it was a Wu Chin Gearing stripped down to the hull and then cosmetically fitted with 5″/38 single mounts off a Fletcher and empty Hsiung Feng I coffin launchers.

LikeLike