(part 1 of a 2-part series)

Every nation that participated in WWII had effects on it’s economy after the war ended. For the Philippines, an unfortunate combination of circumstances meant that these effects lasted longer than probably anywhere else, and most curiously the money itself (the physical printed cash) was an issue decades later.

(American soldiers behind a M4 Sherman advance down the right field foul line of Rizal Stadium in February 1945. The ballpark had been converted into a HQ by Japanese forces. For the Philippines, the occupation was ending but the post-WWII monetary woes were just beginning.)

(A stack of old Japanese Invasion Money stamped by the failed JAPWANCAP scheme of the 1950s.)

stripping of existing currency in 1942

Formal American defense in the Philippines ended in May 1942, but the Japanese invasion was effectively completed before that; with Manila and other major economic cities falling during January and February.

(An American B-10 bomber at Cavite Naval Base being broken down for scrap metal by the Japanese in 1942.)

An organization called Bank Of Taiwan, Ltd.; nominally based in Taiwan (then, a Japanese colony since 1895) immediately liquidated banks in the Philippines of foreign currency and bullion. Accounts were instead refilled with the invasion Pesos (JIM) described below.

Most financial instruments of the Commonwealth’s treasury (paper money, bullion bars, bearer bonds, and coinage) were evacuated out of Manila when it was declared an open city in 1941. In February 1942, with defeat imminent, American troops on Corregidor burned the paper money and bonds, while 20 tons of bullion was evacuated via the submarine USS Trout (SS-202). The coinage, about ₱14 million, was dumped into Manila Bay.

None the less, $20 million in paper US Dollars and bullion was secured by the Japanese from private banks and from individual exchanges for JIM. Compared to the Third Reich (which up until 1944 had trans-border access to banks in neutral Spain, Sweden, Turkey, and Switzerland) this was of less direct use to the Japanese, who were hostile to pretty much everybody on the empire’s periphery by 1942. But there were places, like the neutral Portuguese colony of Macau, where it was useful – in fact, Japanese forces in China were buying supplies from Macau as late as 1945. A less direct effect of the captured American currency was that when held in reserves by Japanese banks, it artificially propped up the Yen.

The USA was aware of this and sought to avoid a repeat if Japan overran Hawaii. Starting in 1942, 48,282,000 individual banknotes ($1, $5, $10, and $20 denominations) were overstamped HAWAII and made the lone money on the Hawaiian islands. Unstamped money (worn banknotes, and the whole supply of $2, $50, and $100 bills) was burned. Had the Japanese invaded Hawaii, the US Treasury would have simply cancelled the overstamped cash.

By October 1944 there was no longer any danger and the overstamping ended; with restrictions on unstamped cash relaxed. The money remained in use. When WWII ended in September 1945, some HAWAII $1 bills were used by demobilizing servicemen as signature cards for departing buddies. A year after WWII ended, the Federal Reserve recalled the HAWAII money. In the American system, which perpetually honors all money at face value, this was quite different than, say, India’s 2016 forced demonitization of certain Rupees. Citizens had no legal obligation to turn in cash; instead banks gathered it up as it passed through deposits and retired it. Little urgency was placed on this and as late as the 1950s, tourists in Waikiki sometimes received HAWAII banknotes in change.

Meanwhile in the Philippines, Japanese intelligence became aware of the silver Pesos dumped into Manila Bay. American POWs and local Filipino civilians were forced to dive for the coins with substandard gear, resulting in fatalities. About ₱1.75 million was recovered.

the JIM story

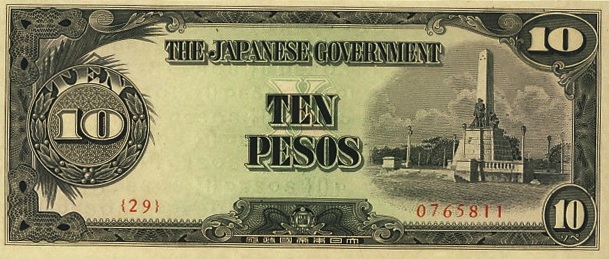

As with most lands it conquered, Japan introduced a new currency to the occupied Philippines. Officially “Dai To-A Senso gunpyo”, it was known in America as Japanese Invasion Money (JIM) and to Filipinos, by less flattering nicknames as detailed later.

For Japan, this was handled by the Southern Development Bank. A “bank” in name only, Southern Development Bank was a de facto arm of the Japanese government to extract wealth from conquered lands through mandatory currency exchanges.

Filipinos were required under penalty of arrest to surrender their prewar currency and exchange it for JIM. All future transactions were to be accounted in JIM.

Cash printed by Southern Development Bank can only crudely be described as banknotes, as bearers had no right to redeem them for specie, no right to exchange them for foreign currency, and no option but to use them. The money was not backed by any tangible bank holdings.

The purpose of JIM was to force the population of the Philippines to bear the cost of their own occupation. Food, supplies, fuel, and services provided locally to the IJA 14th Area Army and the Imperial Japanese Navy were paid for in “money” created out of thin air, as were raw materials shipped back to Japan. Less the trivial cost of printing physical cash, there was no effect on the imperial treasury and it was just an elaborate looting.

This was not an abstract concept. After WWII, American occupation forces in Japan uncovered a 1941 document by Kaya Okinori, an imperial finance minister, outlining plans to extract wealth from a future conquered Philippines via fiat money.

There were three series of JIM. The first was printed in 1942. Denominations were 1¢, 5¢, 10¢, and 50¢ (Southern Development Bank had no interest in buying metal to mint coinage); and ₱1, ₱5, and ₱10. These denominations roughly matched what was in general circulation before WWII.

(A 1¢ banknote of 1942, which was nearly worthless almost as soon as it was introduced.)

(A ₱5 banknote of the first series.)

As with most of the invasion money used around Asia, the Japanese recycled the styling of the former controlling power’s money – in the Philippines case, the USA. Hence, the JIM had a layout and font little different than an American dollar.

The second series was printed in 1943 – 1944. As inflation was out of control, sub-Peso denominations were abandoned. The denominations were ₱1, ₱5, ₱10, and ₱100; with ₱500 introduced late in the series to keep pace with inflation.

(A ₱5 banknote of the second series. By 1944, these were reduced to pocket change.)

(A new ₱500 banknote of 1944.)

The third series, sometimes lumped in with the second, was printed in 1945 and was just a ₱1000 banknote as smaller denominations had been inflated out of realistic usefulness by then.

A misconception is that JIM was “military money”. In fact the IJA issued it’s own separate scrip to pay occupation garrisons. Denominated in Yen, the objective was to shield servicemen from the inflation which Japan was causing in these areas.

(A ¥100 military payment note of WWII.)

Four days after the end of WWII, the imperial finance ministry (which continued to briefly operate under the American occupation) declared military Yen void; with anybody still holding it out of luck. About ¥1.2 billion was thus wiped off the books.

Less the 1945 series, all JIM was printed in Japan. It was shipped by merchant vessel in special boxes which today in 2018 are much more valuable than actual JIM itself.

(photo via Heritage Auctions)

This itself caused problems during WWII, as the American submarine and sea mining offensives gathered steam. Increasingly it was difficult to physically deliver JIM into the occupied Philippines.

Antonia de las Alas was a prewar businessman who half-willingly became involved in the quisling government during the Japanese occupation. Arrested by the US Army at the end of WWII in 1945, he was given amnesty after the Philippines became independent a year later. After his amnesty he offered insight on two examples of the difficulties offshore printing caused: In early 1944, so many ships were being sunk enroute that banks in the Philippines were briefly down to ₱10 million of JIM reserves (barely a blip on the inflation radar by then) and caused a bank run. Later in the war, a Japanese vessel loaded with ammunition and JIM was bombed pierside before it could unload and blew up, raining an entire shipment’s worth of cash onto the surrounding area.

Due to these difficulties, the 1945 series was printed locally. These ₱1000 banknotes started circulating as American forces advanced up Luzon. As the Japanese evacuated Manila, JIM continued to be printed off and on as the retreat’s tactical situation allowed, all the way up until paper ran out in mid-1945. This cash printed “on the run” was of poor quality, using any available ink.

(A poorly-made 1945 ₱1000 JIM, showing ink bleeding through the paper.)

The Japanese also apparently intended a new ₱100 to be part of this series. The US Army captured a horde at Baguio but almost none anywhere else, and it may have never made it into circulation. This is the only JIM that can be considered “rare” today in 2018.

The fact that Japan continued to print JIM even as American troops liberated city after city is somewhat remarkable. In hindsight, it was the least of Gen. Yamashita’s problems. In areas of the Philippines still under Japanese control, use of JIM was still rigidly enforced under penalty of death. It is possibly indicative that late in the war, IJA commanders were beginning to lose touch with the reality on the ground.

other money

During the occupation, other monies circulated, each of which would have after-effects following WWII.

During the 1941 – 1942 Japanese conquest, the Commonwealth government printed a final issue of Pesos. These banknotes should have been exchanged for JIM under threat of arrest, but many were not – either because holders were hedging their bets against the occupation lasting, or, because they feared the Japanese would confuse it with illegal guerilla money and execute them.

After formal resistance ended in 1942, guerilla groups formed in the Philippines and waged war against the Japanese occupation garrison for the remainder of WWII. As the war progressed, these guerilla groups held control of rural towns and in some cases, larger swathes of territory and began circulating their own money.

(A crude guerilla 50¢ voucher of 1942, redeemable for standard currency “after the war”.)

(Understandably photos of actual Filipino guerilla operations are rare. Here, an ambush squad is armed with a typical mixed bag: Arisaka Type 38, M1903 Springfield, and M1 Garand rifles; a Nambu Type 92 machine gun, and a M1917 doughboy helmet. Fates of guerilla kit after WWII varied; most was turned over to the US Army and destroyed, some was absorbed by the Philippines military, some ended up in closets and under mattresses.)

(A ₱2 banknote made with typewriter and office paper from guerillas in Palawan province during 1943.)

(A well-made ₱20 banknote of guerillas in Negros province in 1945.)

Issuance of this money varied. Some guerilla bands just printed whatever they wanted. On the other hand there was an elaborate effort to coordinate monetary policy via clandestine radio broadcasts, with the exiled Commonwealth government in Australia granting permission via radio to a particular rebel group to print a certain quantity of money.

Obviously use of guerilla money in areas firmly under Japanese control was impossible; even possession of it was a capital offense. None the less, it did circulate (sometimes alongside JIM), both in areas under guerilla control and ‘grey zones’ where neither side had a clear advantage.

Life with JIM

In English, Filipinos called the hated JIM “Mickey Mouse Money”. In Tagalog, it was called “Bayong” after a local type of bag; the implication being you needed a sack full of it to buy anything.

During the first 18 weeks or so in 1942 after JIM was made mandatory, it was issued at a reasonable pace of approximately ₱9 million per month. Thereafter, issuance exploded: it was up to ₱16 million / month by the end of 1942, ₱40 million / month by late 1943, and ₱83.3 million / month in mid-1944. Around the time of the Leyte Gulf battle in October 1944 there was over ₱1 billion of cumulative JIM in circulation, about 500% the number of Pesos in 1941, even though the Philippines economy had contracted by 40%.

(A US Army B-25 Mitchell overflies a burning prewar American building and a wrecked Ki-43 “Oscar” during a raid on Clark airbase late in WWII.)

With American ground forces now ashore and the imperial navy shattered, many Filipinos felt it increasingly likely that they would not only be liberated, but that Japan would altogether lose WWII. Whatever little faith that had been put in JIM fell away completely and inflation went through the roof.

To keep up, a flood of cash was printed. During a four-week stretch in February 1945 alone, ₱1.3 billion of new JIM currency was introduced. By July 1945 (when Gen. MacArthur declared the Philippines offensive effectively completed), there was an estimated cumulative total of ₱11.148 billion of JIM issued; 5,574% more Pesos than at the start of WWII. Less notes withdrawn from use due to wear and tear, or captured by advancing American troops, about ₱8 billion of “Mickey Mouse Money” was still in everyday use during the last four months of WWII.

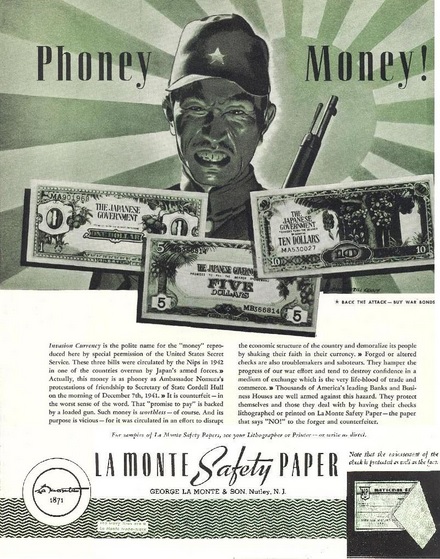

(The American public was aware of JIM’s existence during WWII. This is a wartime ad from a banking paper company.)

The Philippines also experienced what economists call “organic inflation”, meaning there were simply not enough goods to buy. This became acute from late 1944, as American operations paralyzed the Japanese army’s transport system – an unwanted side effect being, it became hard to get food from the countryside into cities and manufactured goods vice-versa.

(Taken from the gun camera of a F6F Hellcat in November 1944, this picture shows prewar American warehouses in Manila being strafed while a cargo ship burns in the harbor.)

counterfeiting

There were two batches of American counterfeit operations during the Japanese occupation. The first came early in WWII. A small lot of prewar Pesos was printed in Washington DC, artificially aged by tumbling the cash in used coffee grounds, and then airdropped to Filipino guerillas. The intent here was that the guerillas would exchange counterfeit Pesos for JIM and then use the later to buy supplies for fighting the Japanese.

The second, and more famous, counterfeiting operation was against JIM itself. On 15 October 1943, Gen. MacArthur requested from the USA’s Bureau Of Engraving the printing of ₱10 million of bogus JIM. Of this, roughly ₱8.3 million was airdropped and made it into circulation, with the balance being lost in the jungle or never sent.

(A counterfeit ₱10 JIM banknote.)

(A counterfeit ₱1 JIM banknote – this one was stamped by JAPWANCAP during the 1950s, a factor in the post-WWII lawsuit described later below.)

Contrary to just about every writing on the topic today, the main objective was not “…to make inflation in the Philippines to harm the Japanese”. The small quantity printed was irrelevant to the inflation woes the Japanese were already causing. The total counterfeit JIM introduced during WWII equaled about a week’s worth of legitimate issuance at the late 1943 level, and represented 1% in circulation at any given moment.

Allied “propaganda money” is often mistakenly conflated with the counterfeiting effort. These were legitimate JIM banknotes captured by the US Army, stamped with mocking slogans, and then airdropped over areas still under Japanese control.

Gen. MacArthur was not keen on the idea as he feared that defiant Filipinos would actually try to use the cash and then be punished by the Japanese. There is no firm record of how much was modified this way during 1944 – 1945, or even a definitive list of the slogans used, and these “propaganda notes” have been rampantly faked since WWII.

Victory money

In 1944, the US Bureau Of Engraving began producing money to be used when the Philippines were eventually liberated. The denominations mimicked those of the US Dollar at the time: ₱1, ₱2, ₱5, ₱10, ₱20, ₱50, ₱100; and ₱500. The “Victory” money was created by the US Congress, but, legally an obligation of the Philippines Commonwealth Treasury (not the US Treasury). They were not legal tender outside the Commonwealth but guaranteed exchangeable at face value to any surviving pre-WWII Pesos, or a 2:1 rate to the US Dollar going forward. No mention whatsoever was made of JIM.

(₱2 Victory Peso.)

(In 1944 – 1945, the US Mint in Denver, CO ran replacement coinage. Shown here is a 1945 Philippines dime.)

In American military lore, the first Victory banknotes were brought ashore by Gen. MacArthur himself, inside his personal wallet, on Leyte island in 1944.

This may or may not have been the case. What is certain is that during the Leyte assault’s second reinforcement wave, a specialized Public Affairs Detachment (PAD) of the US Army brought cash ashore to begin distribution. This scene repeated as the American campaign spread from island to island in the Philippines.

(Distribution of Victory Pesos by a PAD.) (official US Army photo)

THE END OF WWII & THE END OF JIM

Although major operations were over by July 1945, there was no uniform Japanese surrender of the Philippines as a whole. Cut-off Japanese forces continued to hold shrinking pockets of territory and minor islands for the duration of WWII. Remnants of Gen. Yamashita’s forces fought on into September 1945.

(Japanese forces in Cebu province ceased fighting on 28 August 1945, two weeks after the Emperor broadcast his intention to surrender from Tokyo and five days before WWII officially ended.)

From the moment it was introduced, Gen. MacArthur was adamant that absolutely no credence be given to JIM in the Philippines, which he regarded as wholly illegitimate. As policy statements were crafted during WWII, great pains were taken as to not even accidentally offer any legitimacy towards the money.

Starting with Leyte island in October 1944, and then accelerating with the landings on Luzon in January 1945, American forces liberated areas using JIM. Often as villages and towns were secured, Filipinos brought out huge bundles of the hated “Mickey Mouse Money”, demanding that American troops burn it. They were usually happy to oblige.

(American MPs with crates full of JIM.) (photo via National WWII Museum)

(A US Army bulldozer moves a mountain of JIM to be burned.)

Within the American military, there arose a question of what to do with individual soldiers coming into possession of JIM, which was obviously happening left and right. Typically, regulations prohibit possession of enemy money. However Gen. MacArthur was steadfast in that absolutely no credibility be given to JIM as “money”. A practical concern was soldiers engaging in black marketeering, where for example a serviceman would collect a horde of JIM, use it to buy scarce goods on the American side of the frontlines from a Filipino civilian who would then smuggle the cash across to the Japanese side where it was still legal tender and respend it.

To stop this, the International Red Cross punched two holes in captured JIM. This avoided any official American recognition of the money, while serving notice that it had been in American hands and presumably preventing use in Japanese-held areas.

The punched JIM could then freely be kept as a battlefield souvenir. This was supposed to be mandatory across the Philippines theatre. The degree to which the order was actually obeyed is debatable, but in any case it existed.

A less common loophole to help souvenir-hunting soldiers was to obtain a Joint Intelligence Service stamp. As cash is obviously ink on paper, it might possibly be considered an “enemy publication” and this stamp certified that it was of no intelligence value and free for the owner to keep – all the while, avoiding the mention of money.

Even as WWII was still winding down, the Filipino people began to discover some of the problems the 3½ years of JIM was about to cause them. There was no mechanism for converting debts or wealth denominated in JIM into Victory Pesos; and the US Army determined this was a matter for civilian authorities, of which there were none functioning in many places.

condition of the Philippines at the end of WWII

(Watched by a Commonwealth official, two GIs scoop coinage taken from defeated Japanese forces in 1945. Alongside looted prewar Pesos were coins from all over the empire. Most of these coins were melted for their metal content.)

As Gen. MacArthur’s forces retreated in 1941, Manila was declared an open city to spare it. In 1945, Gen. Yamashita did not reciprocate and Manila was leveled in heavy fighting. During his later presidency, Gen. Eisenhower remarked that other than Warsaw, no Allied capital suffered such terrible damage as Manila during WWII. Other cities of the Philippines experienced similar fates.

(The Commonwealth Legislature at the end of WWII in 1945.) (Philippines National Archives photo)

To whatever extend possible, the US Army left combat engineering gear in situ as the front lines advanced forward to assist the local civilian population.

(A US Army portable bridge still in use in downtown Manila during mid-1946, a year after WWII ended.)

Due to the course of of WWII, some equipment landed in the Philippines during 1944 and 1945 would never leave. Starting in June 1945, while American forces were still fighting in the Philippines, staging for the planned 1946 invasion of the Japanese home islands had already started on Okinawa and Guam. Some equipment still in use in the Philippines was more or less already written off strategically by then. Especially in this category were wheeled non-combat vehicles like jeeps, prefabricated military buildings, and so on.

(Half a year after WWII ended, this photo shows a US Army WC-51 truck taken over for a civilian anti-malaria effort in the Philippines.)

(Philippine Airlines was restarted with C-47 Skytrains.)

Before the JIM issue could be addressed the Philippines government had to re-establish a functional monetary system. The Commonwealth, which in 1945 was counting down to independence in 1946, was responsible for backing the Victory Pesos of which ₱1.1 billion (equal to $500.5 million in 1945 or $7 billion in 2018) was circulating. The Commonwealth was also on the hook for the small surviving quantity of 1941 emergency money it had printed, and the larger amount of guerilla money which various groups printed during the occupation. A decision was made to honor all guerilla money to avoid appearing to favor certain groups above others. Combined, the guerilla and pre-occupation money was another ₱223 million.

(The unrepaired Philippines Finance building in Manila a year after WWII ended.)

The Philippines banking system, which in 1940 had been as robust as Singapore’s and Hong Kong’s in the region, was shattered at the end of WWII. During the tail end of the JIM era, many Filipinos spent “Mickey Mouse Money” as fast as possible before it further devalued. So even if JIM had been honored, there was little in savings accounts. Especially in Manila, many bank offices were physically destroyed during WWII and the Philippines telegraph and telephone systems were heavily damaged, making transactions difficult.

(A temporary bank established by the US Army in early 1946, about half a year after WWII.)

A network of temporary banks was set up with US Army assistance. Besides the humanitarian benefit, the Philippines urgently needed to get a taxation system restarted, especially as independence approached. With the population largely using Victory Pesos in a hand-to-mouth direct cash economy, this was impossible so both the Commonwealth and national USA governments sought to get people back into the banking system as rapidly as possible.

Victory Pesos were backed by silver, so an effort was made to recover more of the coinage dumped into Manila Bay during WWII. Two US Navy net tenders were used, USS Teak (AN-35) later relieved by USS Elder (AN-20). During WWII these ships laid ASW nets (chain-link fences attached to pontoons, to stop torpedoes) guarding the entrances to harbors. With the war over, so was their intended mission, but they were well-suited to lifting things off the seafloor.

(USS Teak pierside in Manila during 1945. The ‘jaws’ on the bow handled ASW nets but for the peso operation, the boom crane mid-deck was more useful.) (photo via navsource website)

An effort was made for fast collection by taking a standard 55 gallon drum and punching it full of holes, then dragging it along the seafloor to act as a makeshift dredge. This was not as successful as hoped for, and manned diving soon began. The divers were US Army engineering divers, along with one lone MP armed with just a M1911 to guard the recovered coins.

(A diver descends from one of the net tenders during the 1945 – 1946 recovery operation. The divers worked for half-hour stints on the seafloor followed by a 45 minute decompression ascent.)

The coins were not in a uniform pile on the seafloor, but spread out in batches. Some of the wooden treasury crates had broken open during the descent from the surface and in these cases, individual coins were spread out over a larger area. Many of the intact crates had been eaten by boreworms during WWII, meaning they crumbled as a diver tried to pick them up.

The Pesos were not magnetic but a device called a potentiometer could be trawled about 6′ above the seafloor to give a general alert to silver. To cover more area quickly, the net tenders threw concrete blocks attached to lines over the side, then used their deck winches to tug in various directions to move without using the propeller and rudder.

The coins were collected into a 500 lbs container and winched up to the net tender. The net tenders stayed out for 2 weeks, before returning to Manila where a US Army MP detail took custody of the coins (which were moved aboard ship by hand shovels) on the pier. The net tender then returned to the bay to continue operations.

(T/Sgt Harrison Martin poses for Yank, the US Army’s magazine, with silver Pesos recovered three months after WWII.)

The operation ended in May 1946. A total of ₱5.38 million (almost all of it individual ₱1 coins) was recovered and returned to the Commonwealth Treasury. After the Philippines became independent, a commercial salvor was hired to resume the work, with an additional ₱2.8 million being recovered. In the 71 years since, perhaps a little more has been illegally salvaged by piecemeal diving but less the Japanese, American, and Filipino efforts; about ₱3.5 million was never recovered and presumably remains on the seafloor today in 2018.

JIM as “zombie money”

Inbetween the conclusion of major operations and re-establishment of civilian governance in July 1945, and the planned independence of the Philippines a year later in July 1946, the Commonwealth government began to try to sort out the mess caused by JIM during WWII.

(The pre-WWII Manila City Hall, damaged during the war, served as the temporary Philippines Senate until 1948.) (photo from Life magazine)

The biggest problem was not one-for-one exchanges of cash but rather, trying to figure out a way of unwinding all the transactions done in JIM during WWII. Even as WWII was ending in 1945, a moratorium on JIM-denominated debt repayment was instituted.

In October 1945, about a month and a half after Japan’s surrender, work began on a solution to the problem. Paul McNutt, the final American commissioner to the Commonwealth, crafted a legal mechanism by which this might be done. However the Commonwealth’s Senate did not adopt it. Instead, Filipino economists devised a sliding scale of how they felt JIM gradually devalued compared to the prewar Peso between 1942 – 1945, and proposed that all wartime transactions would now be pegged to that.

On 18 January 1946, a Commonwealth law was passed to this effect. Debts (including prewar debts) paid off in JIM were considered satisfied; while debts incurred during the occupation would be handled with portions paid in JIM as valid, and any remaining balance due now payable in Victory Pesos pegged to the scale. Remaining deposits in JIM (of which there were realistically little) were voided, as was redemption of physical JIM cash.

As a vestige of prewar American control of the Philippines, the USA’s President (Harry Truman) retained power to block Commonwealth laws in the 10-month interim between the end of WWII and the end of American rule. Previously during the Commonwealth era, this right had been rarely used.

However on 7 February 1946, President Truman blocked the law. In a very terse statement (Truman actually used the words “Mickey Mouse Money”), the President stated that even partial redemption of JIM ran counter to the illegitimacy policy maintained throughout WWII, and would harm, not help, reconstruction in the Philippines. Truman added that the policy was unfair as it would put collaborators on equal footing as the guerillas.

There may have been other factors in the President’s mind. Due to high mortality rates in 1945, redemption of JIM-denominated life insurance policies would have driven insurance companies in the Commonwealth bankrupt. Some of these insurance companies were reinsured by American companies, who would have likely run a fire sale of assets to compensate, driving down the stock market prior to the 1946 midterm elections, in which Truman’s Democrats already expected big losses.

In any case, the Commonwealth considered what to do next. Two options studied (neither legal) were to simply ignore Truman, or, for the Commonwealth to try suing the USA in the USA’s Supreme Court. The clock to independence ran out before either was tried.

The Philippines became independent on 4 July 1946. Oddly enough, the Victory Pesos remained the new country’s legal tender, with the Philippines itself not printing currency until 1949. Victory Pesos remained legal tender alongside the new money until 31 December 1957, and in some cases could still be exchanged at banks until 1967.

(A US Army general presents his WWII M1 carbine to a general of the new Philippines army at the ceremony of independence, 4 July 1946.)

(WWII-vintage P-51 Mustangs equipped the now-independent Philippine air force.)

The JIM issue remained unresolved as the Philippines became independent. Quite honestly, it was never fully addressed after independence either. As years went by, some banks opted to write off JIM-denominated debts to clear bad loans from their books.

(Largely forgotten today, the Commercial & Financial Chronicle was a longtime competitor of the Wall Street Journal. In March 1947, a Filipino economist explained the severe problems being caused by the legacy of JIM.)

One notable legal case came in 1948. Called the “Haw Pia Case”, it set something of a precedent for JIM issues in the post-WWII legal system. Here, a woman named Haw Pia took out a ₱8,000 mortgage in prewar Pesos during September 1939. When the Japanese seized her bank in January 1942 and forced the use of JIM, she still owed ₱5,103. During WWII she easily paid this off in full, as the JIM suffered massive inflation. After WWII, the bank notified her that the JIM payments were voided, and put a lien on her house demanding back payments, with interest, in Victory Pesos. About 12 weeks before the Philippines became independent, a lower court ruled in the bank’s favor, in line with the USA’s position on JIM. Haw Pia’s appeal was however heard by the Philippines Supreme Court after independence. The verdict was reversed and her JIM payments were ruled valid.

(Haw Pia’s house is long gone; today in 2018 the Manila address belongs to a cafe on the ground floor of a multistory development.)

Ironically, one of the legal precedents the Filipino court referenced to counter President Truman’s 1946 opinion was the USA’s own policies towards the handling of occupied Germany’s banks in the brief span between the end of WWII and the 1948 case.

One quasi-official position taken was sometimes called the “double-dipping rule”. Here, the Philippines leaned towards requiring banks to either honor both payments and debts in JIM, or dishonor both, but not cherry-pick between the two. The idea was that creditors and debtors would find “a wash” between the two and discourage lawsuits. Generally speaking, the Philippines sought to place the JIM legacy’s burden on banks rather than individuals. This was politically popular but retarded the ability of Filipino banks to create credit after WWII.

(Far from the severe problems it was causing in the Philippines, now-worthless JIM hit the USA’s hobby market as fast as demobilizing GIs could sell it. This is from a 1946 issue of Popular Mechanics magazine.)

the JAPWANCAP fiasco

As mentioned previously, many Filipino civilians eagerly burned the despised “Mickey Mouse Money” in 1945. Others did not. This was not illogical. As Gen. MacArthur had already ruled JIM completely worthless, it was impossible for it to decline any more past zero. On the other hand, there was possibly an outside chance that somehow, sometime in the future at least a partial redemption might be made on it.

Conceptualized while work on the 1951 treaty formally ending WWII for occupied Japan were ongoing in San Francisco, the Japanese War Notes Claimant Association of the Philippines (JAPWANCAP Inc.) was a remarkable attempt to obtain value out of the old JIM banknotes, years after WWII had ended and long after the rest of the world had forgotten that the money even existed.

JAPWANCAP began operating in 1952 and was legally incorporated on 8 January 1953. It was a clearinghouse for remaining JIM in the Philippines, with the goal of using political lobbying and lawsuits to get compensation for the cash. Filipino citizens would present JIM to JAPWANCAP along with a small membership fee. Each banknote was stamped, and a voucher presented to the claimant.

(A JAPWANCAP voucher for ₱10,000 of JIM.) (photo via guerilla-money.com website)

The stamped cash was stored in a huge vault, meanwhile (assuming JAPWANCAP was a success) the claimant would later redeem the voucher for an appropriate amount of current money – be it Pesos, Dollars, or Yen; depending on which of JAPWANCAP’s maneuvers succeeded.

JAPWANCAP claimed membership of 150,000 (historians feel 120,000 was actually more likely) and amassed a staggering mountain of old JIM; tens of millions of worthless individual banknotes with a combined face value of ₱3.5 billion. This was quite astonishing at the time, as it represented only slightly less than half of the total thought to have still been in circulation when WWII ended in 1945.

(One of the styles of stamp JAPWANCAP used.)

The director of JAPWANCAP was Aldredo Abcede, who had been a losing candidate for the Philippines senate in 1953. He later announced his candidacy for the 1957 Philippines presidential election, with the core of his campaign being a promise to redeem JIM, through his JAPWANCAP scheme. The Philippines government refused to add his name to the ballot on the grounds that his campaign was fraudulent, in that the whole JAPWANCAP scheme was far-fetched and unlikely to succeed.

(Abcede’s signature was used in another of the stamp styles. Collectors call this the ‘typo style’ on account of “safe keping”.)

JAPWANCAP’s first effort at finding somebody to redeem the “Mickey Mouse Money” was a rambling letter mailed to the United Nations in late 1952. The U.N. did not take the matter up.

Filipino courts denied all of JAPWANCAP’s efforts. Obviously as the Philippines had not existed as an independent country during WWII, it was impossible for the postwar government to have been responsible. If blame existed, it lie with either Japan or the United States; and diplomacy was not in the court’s realm.

JAPWANCAP was frowned upon by the Philippines government throughout the company’s rise and fall. Abcede was portrayed as a hustler, swindling Filipinos out of “membership fees” with false hopes. More importantly, the Philippines had negotiated $550 million ($5.12 billion in 2018 dollars) of reparations from Japan, paid in annual installments over 20 years. There was concern that if any of JAPWANCAP’s strange maneuvers somehow was successful, Japan would void the reparations agreement.

(Philippines Veterans Bank, which still exists in 2018, was originally capitalized with $60 million of reparations from Japan to provide banking services to ex-guerillas and Filipinos who had served in the American military during WWII.)

Of the reparations money received, not one cent was directed towards redemption of old JIM.

Next JAPWANCAP tried Japan. The lawsuit was two-fold: 1) redemption of the stamped JIM currency in it’s vault, and 2) compensation for the inflation of the currency during WWII. The case was not successful. The Japanese court ruled that it was bound by the San Francisco treaty which stated that WWII claims against Japan were settled on a nation-to-nation basis, not individually. As to the inflation, the court questioned if some was due to the empire’s declining war fortunes. Indeed, modern economist reconstructions of the inflation show that it was non-linear; jumping after American victories in the Pacific. As Japan obviously did not intend to lose WWII, this questioned the country’s legal liability for the inflation.

Another point raised was a 1945 Imperial Japanese Army document (Socho Shi No.23) which concluded that American radio propaganda against JIM created a self-fulfilling prophecy, in that the fear of inflation led sellers to demand more JIM from buyers, devaluing the currency and seemingly confirming the propaganda broadcasts, starting a snowball effect.

JAPWANCAP’s final hope was a lawsuit against the United States, which was filed in the US Court of Claims in December 1964. JAPWANCAP made three claims : 1) The total of stamped JIM in it’s vault 2) The total counterfeited by the USA during WWII – here, it did not physically need the money as now-declassified US Army records showed it 3) Compensation for vaguely-defined subsequent costs of JIM. The total sought was $9.99 billion ($79 billion in 2018 money).

On 17 February 1967, the case was thrown out on a technicality. American law requires claims to be filed within 6 years of the last offense. Here, several dates were suggested:

•19 April 1945 (restart of post-occupation banking in Manila)

•circa ~July 1945 (last known printing of JIM)

•2 September 1945 (end of WWII)

•4 July 1946 (end of the USA’s rule in the Philippines)

•28 April 1952 (1951 San Francisco Treaty enters force)

In any of these dates, the 6-year window had lapsed so the court dismissed the case without judging it’s merits. A request for appeal was denied.

That was the end of the road for JAPWANCAP. With no pathway to success remaining, the scheme faded in the late 1960s and vanished. At some point, the stamped cash was released back to the public and today, is so common as to add or detract little collectible value. Some collectors actually seek different varieties of JAPWANCAP stamp, as JIM itself is so common.

postscript

In the 74 years since it was last printed, not one cent of JIM has ever successfully been redeemed.

When economists study the after-effects of WWII, the topics are usually the 1950s miracles in West Germany and Japan, the decline of the British Pound, or the rise of new “tigers” like Singapore. The Philippines is an unfortunate counterpoint: there was no real solution, it was not the Philippines own fault, and there was never a happy ending. While other postwar economies grew in the 1950s, the after-effects of “Mickey Mouse Money” hung like a millstone around the neck of Manila’s banking sector long after WWII.

Sadly as late as the 2000s, the Philippines government still occasionally received inquiries from now-elderly Filipinos checking if their JAPWANCAP certificates were ready to be redeemed yet.

Today in 2018, the Piso (the currency since given a Tagalog name) is worth less than 1% of the Victory Peso. In 2017, the Philippines began consideration of phasing out cent denominations, as (just like under JIM) they were no longer realistically usable.

(part 1 of a 2-part series)

What a fascinating article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed fascinating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This reminds of the robbery through currency that the Germans enacted in Greece and the utter devaluation of the drachma that caused. I see that the Japanese did something similar to the Philippines.

LikeLiked by 1 person