Photos of USS Missouri and USS Wisconsin firing 16″ rounds at Iraqi targets in 1991 are well-known as the last instances of battleships in combat. Less widely known is their operations with Tomahawks during that war, and even less, about how cruise missiles ended up on WWII battleships in the 1980s to begin with.

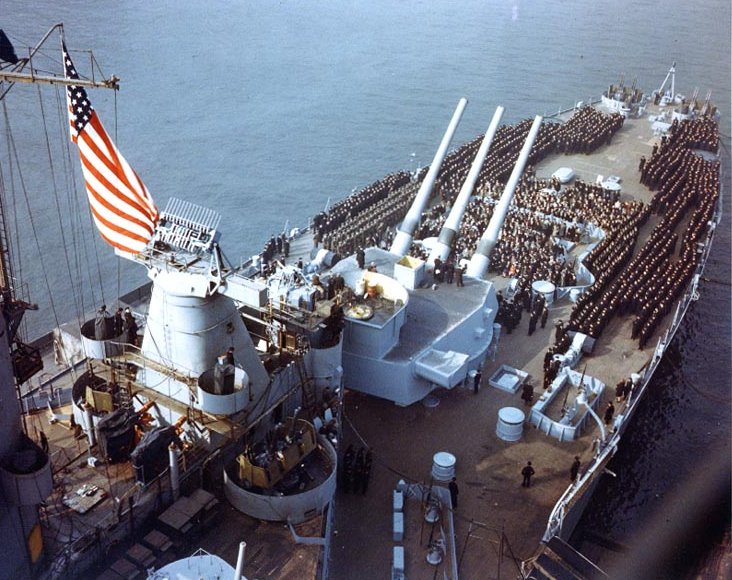

(USS Wisconsin during WWII.)

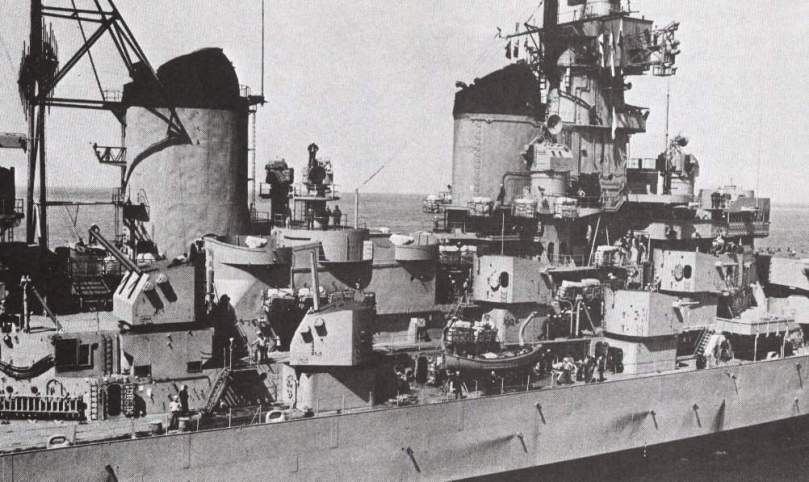

(USS Wisconsin firing a BGM-109 Tomahawk during operation “Desert Storm”, four and a half decades later.)

As a result of the mass decommissioning of remaining WWII-era gun cruisers after the Vietnam War, the US Marine Corps was left with a shortage of naval fire support. The first suggestion to reactivate the Iowa class came in 1980, during President Carter’s final months in office. Funding was requested from Congress as part of the (unrelated) B-1 bomber project, but not approved.

After the 1980 election, the defense analyst John Lehman (soon to be Secretary of Defense) mentioned the concept to President-Elect Reagan. It was suggested to reactivate only two (USS New Jersey and USS Iowa) to satisfy the US Marine Corps need for gunfire support and as mounts for the new Tomahawk cruise missile.

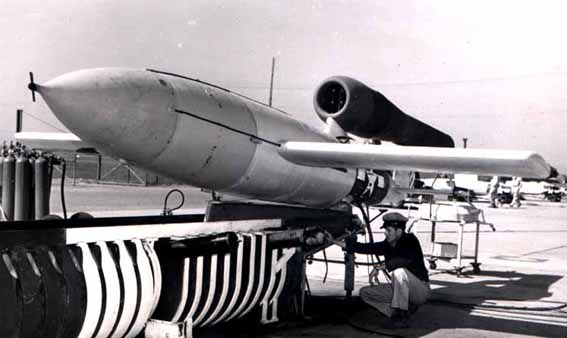

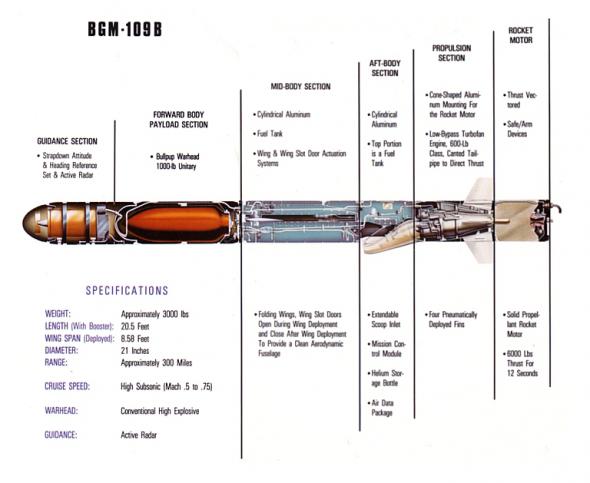

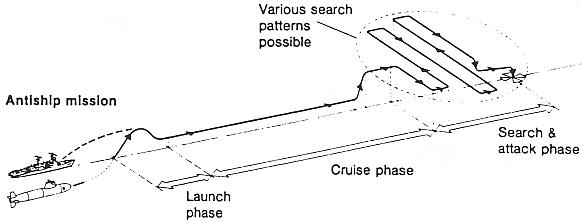

(Early-1980s promotional material for the BGM-109 from General Dynamics.)

Reagan was enthusiastic and instructed that funding for all four be sought. The idea was tagged to a suggestion for reactivating USS Oriskany (CV-34), an aircraft carrier launched during WWII. It was thought that the carrier would be more popular and that the battleships could ride it’s coattails. In 1981, the battleship request to Congress was approved for the 1982 naval program. (Ironically, the USS Oriskany reactivation was never approved.)

(A 1981 Government Accounting Office (GAO) document on the proposed reactivations of the battleships and USS Oriskany.)

The Iowa class had everything the US Navy’s “Tomahawk lobby” could want. They were highly survivable, as fast as any nuclear-powered surface ship, had excess tonnage; and most importantly, were already built. There would be no teething period for their hullforms or propulsion plants; long since proven during WWII. The cost of reactivating them would roughly equal the cost of a new destroyer each. The only foreseen downside was their high peacetime operational costs.

Privately in the US Navy it was considered to use the 16″ guns aboard the battleships merely as a trojan horse to Congress, to get the ships in service as mounts for new radars and cruise missiles. Once reactivated, the US Navy would announce a plan to half-heartedly man the Mk7 16″ guns with rotating pools of reservists. A more drastic plan was to man only one 16″ turret and seal off the others. Thankfully neither idea was proceeded with.

(AN/SPS-49 air search radar console aboard the reactivated USS Iowa.)

USS New Jersey was a special case. It was suggested to remove her aft 16″ turret and install enhanced helicopter facilities and a 48-cell missile vertical launch system (VLS). This 1980s idea is often mistakenly confused with the “Phase II” proposal of the 1970s, which suggested replacing the aft 16″ turret with a VLS and ski-jump for AV-8 Harrier planes. The turret removal and VLS installation would have delayed that battleship’s reactivation by up to 4½ years. Congress refused this idea and all four Iowa class recommissioned on schedule in a common configuration.

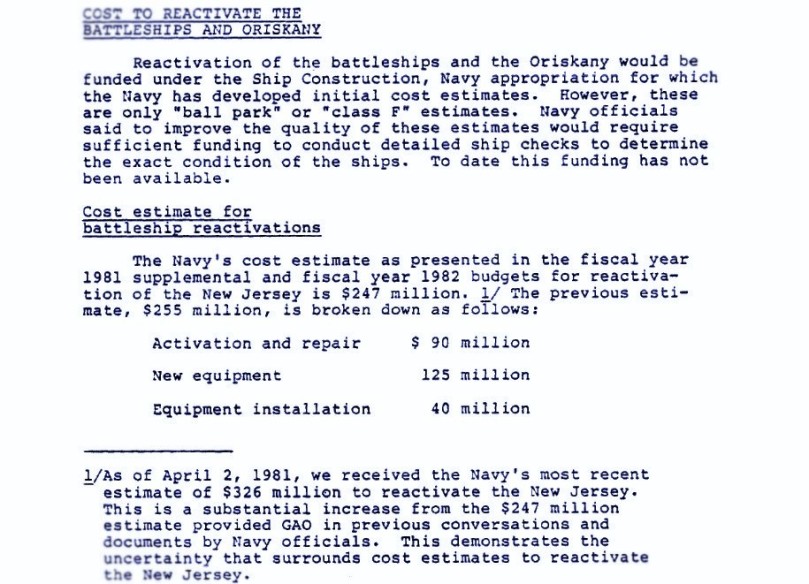

(GAO document from 20 April 1981, detailing the planned deletion of USS New Jersey’s aft 16″ turret, and also the concerns about the concussion from the WWII 16″ guns on modern systems. Contrary to the document, armored launchers were in fact completed in the nick of time for USS New Jersey’s recommissioning.)

After the idea of mating WWII battleships with 1980s missiles received Congressional blessing, the most immediate question was how to install them. The first idea was to simply seat the metal shipping containers on deck and fire the Tomahawks out of them, as submarines do.

(Tomahawk missile in it’s factory canister.) (photo via General Dynamics)

These canisters were tested as resistant to a 12″ drop onto concrete. However it’s doubtful these canisters could have withstood a rough Atlantic winter, and in any case they would have left the missiles vulnerable to tampering, vandalism, or shrapnel damage.

(Greenpeace protesters harass USS Iowa.)

The shrapnel concern was not minor. A 1980s-vintage Soviet anti-ship missile impacting the WWII armor belt or turrets would not cripple a battleship, but it would produce tremendous amounts of shrapnel, blast, and flying debris. This would be magnified if the missile hit a 5″ turret or superstructure. Tomahawks themselves were full of jet fuel and ordnance, and any damage would present a secondary hazard to the battleship.

A more immediate issue was the concussion of the Mk7 16″ guns. Tests already showed that a planned installation of RIM-7 Sea Sparrow SAMs would fail, as there was nowhere that the launchers could be shielded from 16″ gun concussion and still have a useful firing arc. SAMs were deleted off the reactivations, and it was obvious that the even more delicate Tomahawks needed a solution if they would avoid a similar fate.

(USS Iowa firing a full 16″ broadside. The water shows the spread of the tremendous concussion wave from the Mk7 gun muzzles.)

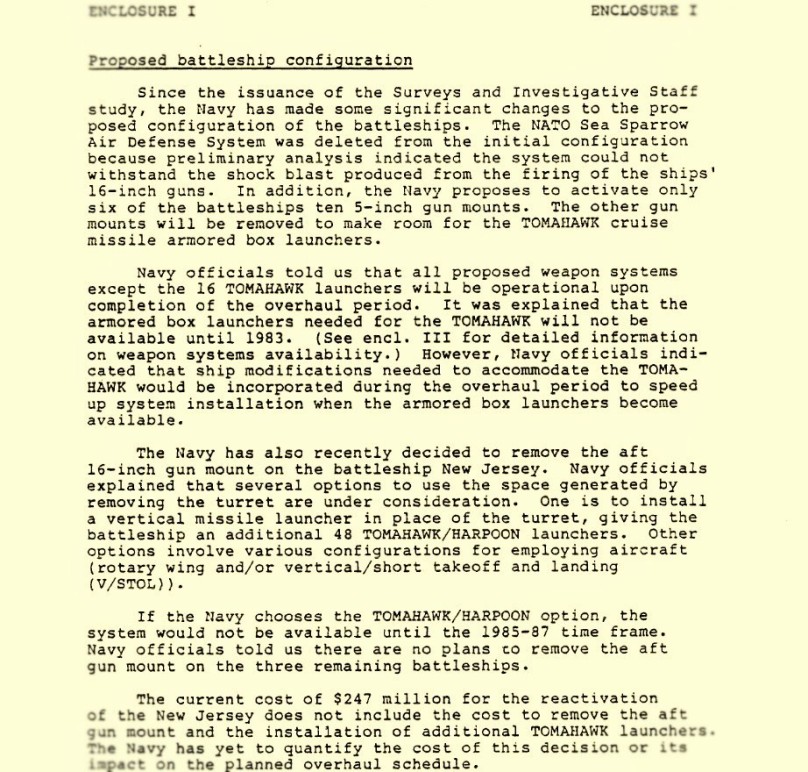

A second idea was to develop a ceramic-coated tubular launcher for the BGM-109, like the Mk141 for the RGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missiles installed on the battleships as shown below. These offered protection against rough seas and vandalism, and limited protection against concussion and shrapnel.

However with Tomahawks they would still be somewhat vulnerable. Additionally this would take time to design, and also would fail to satisfy the US Navy’s security protocols for housing nuclear warheads at sea. What was needed was an armored launcher.

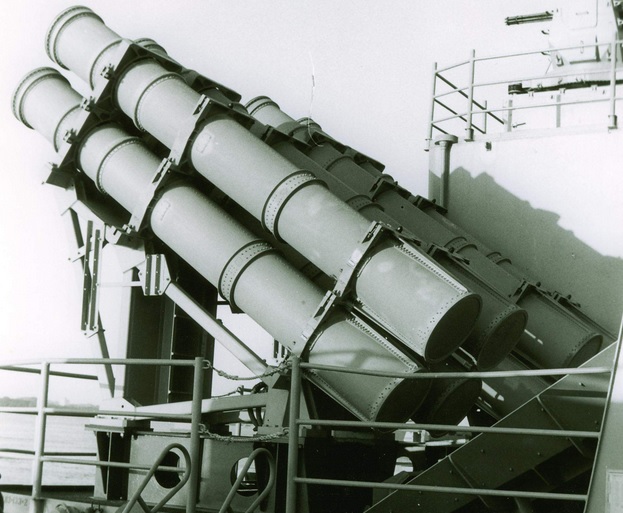

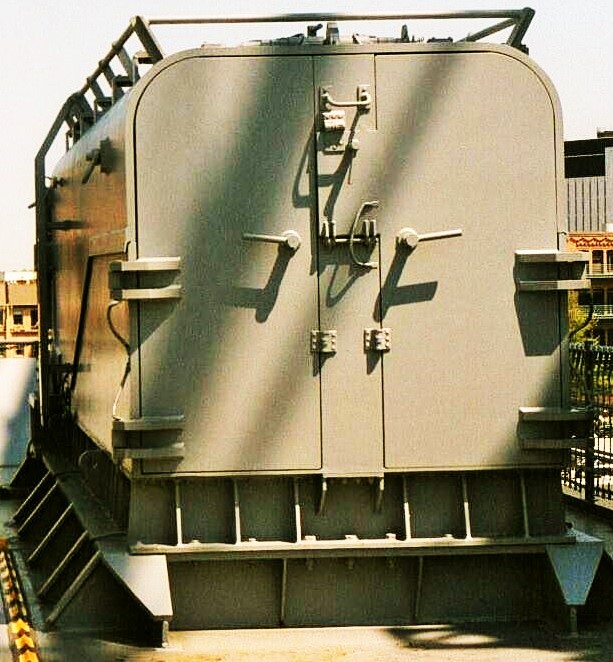

Mk143 Armored Box Launcher

The ABL measured 7′ wide by 6’7″ tall by 23’2″ long, and weighed 26 tons empty. They were made by Unidynamics of St Louis, MO and designed in less than a year. Made of electrowelded steel alloy armor, it housed four Tomahawks of any type. To fire, a hydraulic jack raised the top half to 50º and as soon as the missile was spun up from the battleship’s targeting system, it was ready to fire.

(Closed ABL aboard USS Wisconsin.) (photo by Ronald Barker)

(ABL fully raised with access doors opened.)

(A somewhat uncommon photo of an ABL aboard USS Wisconsin midway through the opening sequence. This also shows the angled exhaust deflector outboard of the launchers.)

Part of the Mk143’s success was that it was a “bolt-on” launcher; requiring no hull cuts. All that was required was a small deck penetration for electrical and datalink cables. Compared to earlier schemes for canisters, the cost of the ABL was offset by only having to wire each quad launcher once, as opposed to every individual canister. ABLs were installed on battleships, cruisers, and destroyers.

(ABL aboard USS Wisconsin, showing how it was bolted to a steel base welded onto the deck.)

(ABL aboard USS New Jersey showing it’s opened circular back-blast hatches, and cable distributor boxes on the launcher behind it.)

Despite the fact that the US Navy has long since retired the ABL, it has never revealed the ballistic performance of the armor. By best estimation it was resistant to direct hits by 12.7mm rounds (as used in the USSR’s widely-exported DShK) or smaller calibers in any circumstances, and possibly 20mm at certain impact angles. In any case the main focus was not direct battle but rather to protect the Tomahawks from shrapnel, blast, and weather; in addition to high-security storage.

The ABL could only be reloaded pierside. The missiles were loaded inside their sheet metal transport containers and blew through a frangible nose cover at launch. The booster rocket’s exhaust exited through an armored circular hatch on the ABL’s rear.

(Taken aboard a Virginia-class atomic-powered cruiser, this photo shows how ABLs were loaded.)

(A Tomahawk being fired off USS Wisconsin during Desert Storm. The back-blast circular hatch is visible in the extreme lower right.)

Aboard the recommissioned Iowa class, eight ABLs were installed for 32 total missiles. Four launchers were sited aft around the base of the Mk38 16″ gunfire control tower. These were angled obliquely firing forward.

(USS Iowa being built during WWII, showing the angled AA gun platform around the base of the aft Mk38 gunnery director tower. The odd-looking radar atop it is a Mk8, which was later replaced by Mk13.)

(Roughly the same area of USS Iowa in 1988, with ABLs having replaced the light-caliber AA gun tubs of WWII.)

(A battleship’s rear starboard aft ABL raised and ready to fire.)

The other four ABLs were amidships, pointed abeam and firing crossdeck. During WWII, this area had been reserved for Mk4 quad 40mm AA guns. As the Iowa class was under construction, additional 40mm AA guns were jammed into this area, as were even smaller 20mm AA weapons. Addition of this new platform deck, on the 03 level, also mandated deleting four of the ten WWII-era twin 5″ guns, which was more than fine with the US Navy as it would reduce the battleship’s crew size. By the 1980s these guns were no longer viable as AA weapons and served only for shore bombardment.

(In this photo of USS Missouri’s WWII smallboat, the so-called “flying galleries” of single 20mm mounts is shown. These freestanding amidships platforms were added to beef up the AA fit. All were removed during the 1980s modernization to make way for the new TLAM deck.)

(USS Missouri’s amidships area during WWII.)

(The new amidships area of USS Missouri in 1988.)

(USS New Jersey was unique in that during the brief Vietnam-era reactivation, empty 40mm tubs in this area were used by CHAFFROC, seen here under canvas. This was a launcher for modified Zuni rockets that dispensed radar-blinding metal chaff. The 20mm “flying galleries” of WWII were already removed altogether. The searchlight pedestals carried in Vietnam were removed in the 1980s reactivation.)

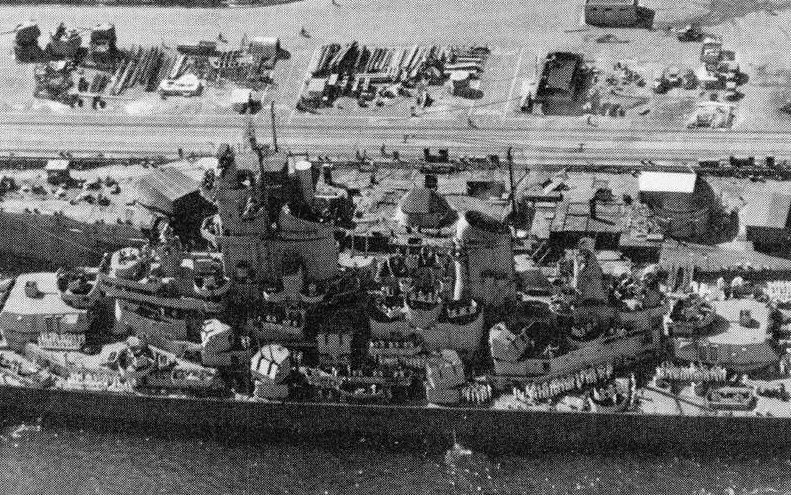

(USS New Jersey in the shipyard during March 1982.)

(USS Wisconsin at Pearl Harbor during WWII, showing the original amidships area, packed with 40mm and 20mm AA guns. The hulk inboard is USS Oklahoma, which was refloated but never repaired.)

(USS Wisconsin during the reactivation in 1986. The amidships area is still in the WWII configuration but without any guns. The WWII twin 5″ turrets have been uprooted and stowed on deck, they were refurbished ashore. Many of the Korean War-era radars had already been removed.)

(The amidships area of USS Wisconsin during Desert Shield in 1990, showing the new platform deck with ABLs. The angled steel piece was to deflect the Tomahawk’s exhaust at launch.)

(USS Iowa during the modernization on 23 September 1983, with the new amidships platform built and bases welded on, but the ABLs not yet installed.) (photo via Navsource website)

The topweight of the new platform, plus the ABLs on it, was cancelled out by the removal of the 5″ mounts plus a lowering of the overall structure closer to the ship’s centre-of-gravity.

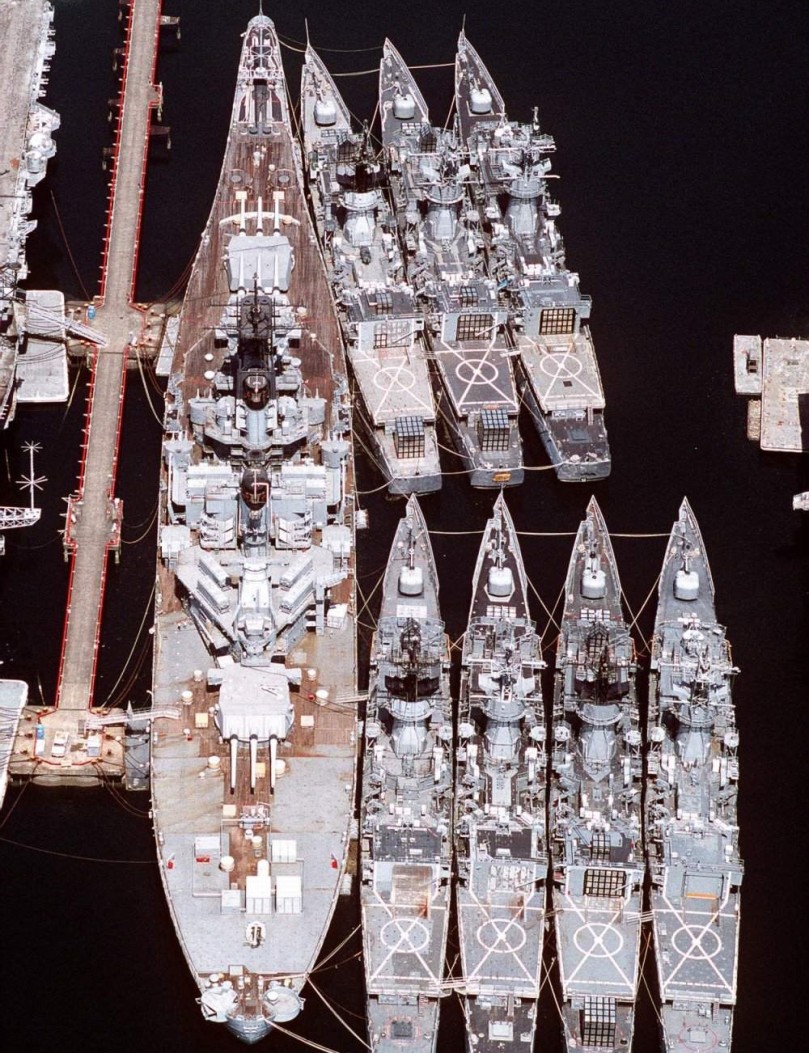

(The finished look aboard the reactivated USS New Jersey: All eight ABLs, the sixteen Harpoons, and two of the four Mk15 Phalanx automated 20mm gatling guns for use against incoming missiles.) (photo via General Dynamics)

Overall the ABL was a tremendous success. However it was only ever intended to be a temporary stop-gap until sufficient VLS-fitted ships were available to the fleet.

(The US Navy planned for vertically-launching Tomahawks all along, but this capability would not be ready until the mid/late-1980s. The elderly USS Norton Sound (AVM-1) was the VLS test ship. USS Norton Sound had originally been a seaplane tender during WWII.)

After USS Missouri left service in 1992, the atomic-powered cruisers also decommissioned throughout the decade, and finally the ABL-fitted Spruance destroyers in the early 2000s. The ABL then left service, having served it’s purpose well.

TLAM

Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM) is the official abbreviation for both conventional versions; the unitary warhead and submunitions design. It is a cruise missile, which means it flies horizontal like the V-1 buzz bombs of WWII, not in an arc like ballistic missiles. The base cost (in 1989 dollars) was $1.6 million per missile, or $3.14 million in 2017 money.

(Very early concept art for the Tomahawk, which actually doesn’t differ much from the actual missile today.)

This was not the US Navy’s first attempt at taking land-attack cruise missiles to sea. During WWII, the JB-2 Loon was designed (or more accurately, reverse-engineered from crashed V-1 buzz bombs) and 75,000 were planned. The contract was immediately terminated when WWII ended and only 1,391 were built. The Loon suffered from all the limitations of the V-1. After WWII the US Navy adapted it for use off surfaced submarines, but it failed to find a useful niche.

(Loon missiles, ashore during WWII and aboard USS Cusk (SS-348) after the war.)

In the mid-1950s, some WWII-veteran cruisers were adapted to fire the RGM-6 Regulus I, a nuclear cruise missile. The last of these left service in the early 1960s.

(USS Los Angeles (CA-135) firing a Regulus. The launcher was fitted where the seaplane catapults had been during WWII.)

The Tomahawk’s origin came long before reactivation of battleships was considered. In 1971, the US Navy briefly considered developing a cruise missile which could be fired from existing ballistic missile launchers. In October 1975, the US Navy opened a competition for a “SLCM” (submarine-launched cruise missile) which would enable Los Angeles-class atomic submarines (set to begin commissioning in 1976) to attack ashore targets with great precision at extreme ranges, without hull changes or loss of traditional submarine abilities. To do this, it would need to be 21″ in diameter (to fit inside a torpedo tube), have an air-breathing engine, and an onboard guidance correction system.

(A non-flying mockup of the Tomahawk in the 1970s.) (photo via General Dynamics)

(A wind tunnel model, here upside down, being researched in the 1970s.)

It quickly became clear that if it were possible to launch such a weapon from a submarine at periscope depth, it would be just as east to also fire it off a warship already on the surface.

In February 1976, the ZBGM-109 design by Convair beat Vought’s ZBGM-110 and won the contract. Convair had been formed during WWII by a wartime merger of the Vultee and Consolidated aircraft companies. By the 1970s, Convair was just a brand name inside General Dynamics. Tomahawk entered service in 1980 aboard submarines and in 1982 aboard battleships.

(The propulsive and flight surfaces section of the ZBGM-109 in the mid-1970s.)

BGM-109C is the unitary conventional warhead model, and the most common type of Tomahawk. The BGM-109C is 18’3″ long and 1’9″ in diameter with the surfaces tucked in. Once deployed the wingspan is 8’7″. The missile weighs 2,900 lbs at launch and is powered by a small Williams F107-WR jet engine. The missile travels at 478 kts and has a maximum range of about 1,350 NM. This is the absolute (fuel exhaustion) maximum; realistically 960 NM is a better figure which is still impressive.

(BGM-109C Tomahawk in flight.)

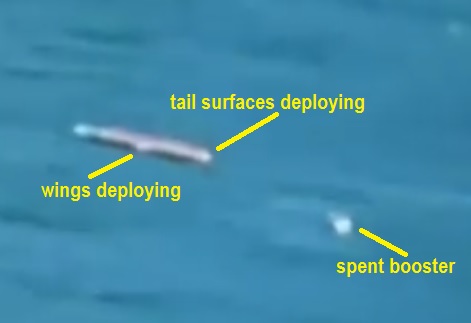

To launch, a Mk106 solid-fuel tail rocket is used. This produces thrust 200% of the missile’s weight for twelve seconds. During storage and launch the control surfaces are retracted. The rocket is attached to the missile by a fairing which splits off after the Tomahawk has cleared it’s launcher.

(Close-up of the Mk106 launch booster. This was a warshot Tomahawk fired from USS Wisconsin during Desert Storm, and also shows the mottled camouflage pattern used during that war.)

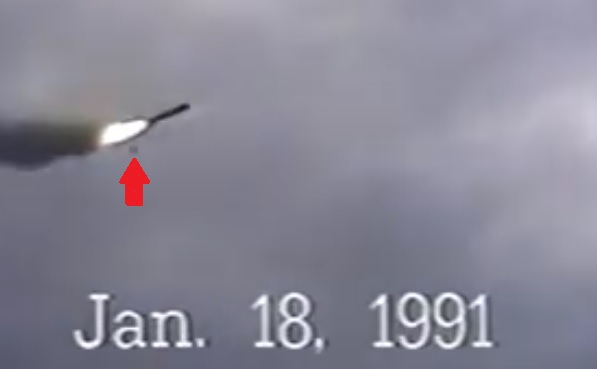

(The arrow points to a piece of the fairing inbetween the booster and the missile, which falls off after the weapon clears the ABL. This was a warshot Tomahawk fired off USS Missouri during Desert Storm.)

(An inert BGM-109C showing the booster separation and start of the level flight surfaces deployment.)

The missile performs a steep pop-up; and then either levels off or descends to a lower cruise altitude. When the control surfaces deploy, the spent booster rocket falls away. The airscoop drops down, enabling the jet engine to start. The four tail fins are hinged and fold out, while the wings swing out of the fuselage, the resulting slot being covered by a fold-down flap. The Tomahawk flies in the same manner as an airplane.

(Tomahawk with airscoop and flight surfaces fully deployed.)

(A 1977 mockup of the wing stowage slots, showing the flap and also the small cross-section of the wing.)

(Tomahawk wings are computer-milled from one solid slab of aluminum.)

Tomahawks are targeted by a memory unit aboard the firing ship or submarine. This unit contains hundreds of target coordinates and mission profiles; pretty much anything the vessel might be asked to attack in it’s expected sailing area. Aboard the reactivated Iowa class, the Tomahawk center (including the memory bank and launch controls) was inside the armored conning tower, aft of the lower (flag) bridge. During WWII, this area had housed bulky vacuum-tube radios and a classroom.

(Location of the Tomahawk control room aboard USS Wisconsin.)

If needed, additional targets could be downloaded via the battleship’s AN/WSC-1 satellite communications gear. Contrary to Hollywood lore, it was not possible to maliciously retarget Tomahawks onboard the battleships with a personal computer, or the such.

(The external ‘bowl’ antenna for USS Iowa’s AN/WSC-1 system. A duplicate was on the conning tower, so the ship could find a satellite at any latitude without maneuvering. The big oblong radar in the photo’s left is the Mk13 which spotted the rear 16″ guns.)

The TLAM is guided by the AN/DPW-23 TERCOM (terrain comparison) system, which takes radar “snapshots” of the ground underneath and compares it to maps in computer memory, making course corrections as necessary. After firing, no further action was required by the battleship.

(The three black squares are downwards-looking TERCOM sensor heads. This bright orange Tomahawk was an inert test shot from a non-production launcher.)

Looking nose-on, the TLAM has a very small (equivalent to about 2’²) radar cross-section, and it’s skin is treated with radar-absorbent coating. It’s attack altitude is often beneath the minimum of defensive radars, and masked by terrain. It is very hard to defend against, but not impossible if detected early enough. As it flies so slow, any Soviet-made fighter from the MiG-19 “Farmer” onwards could chase it down, assuming it was detected in time. Low-altitude SAMs and radar-guided AA guns can also engage Tomahawks.

The BGM-109C’s warhead weighs 1,000 lbs. The missile can be set to either slam directly into a target horizontally, dive on it vertically, or fly at very low altitude and self-detonate right above it; which is useful for targets in revetments.

(Test shot of a BGM-109C)

(A 1986 test of the BGM-109C against a reveted warplane, in this case a retired A-5 Vigilante.)

Missiles for training, tests, etc were painted in blaze orange or promotional schemes. Operation “Desert Storm” in 1991 offered a rare glimpse at the colors of actual live warshot Tomahawks aboard the battleships. The reason for the two color schemes, if there was one, is not known.

(One scheme was had matte greyish-green on top and haze grey on the underside, somewhat reminiscent of camouflage applied to warplanes during WWII.)

(The other was overall air superiority grey, as used by modern US Air Force types.)

The BGM-109D is the submunitions version of the TLAM. It is identical in all regards to the above from the wings on back, and has an identical launch procedure. The attack profile is different as it is intended to overfly the target area. The warhead compartment is filled with 166 BLU-97/B cluster munitions in 24 separate dispensers. These are 7″-long cans weighing 3½ lbs each, slowed by a drogue.

(BGM-109D in flight.)

(BGM-109D deploying submunitions.)

The BGM-109D can either dispense submunitions en masse, or, fly a brief series of turns to further spread them around several spots. Even if all at once, the BLU-97/Bs discharge diagonally and descend erratically, covering a large area. The submunitions version was intended to be used against “area” targets like an artillery battery, lineup of parked warplanes, etc.

(BLU-97/B submunitions impacting around a ZSU-23-4 self-propelled AA gun.)

TLAM-N

BGM-109A or nuclear land-attack Tomahawk (TLAM-N), was the atomic model (it was also referred to as TLAM A). It differed little from conventional Tomahawks; with identical propulsive components and airframe. The flight characteristics were similar to the conventional versions, and it’s attack profile was generally the same.

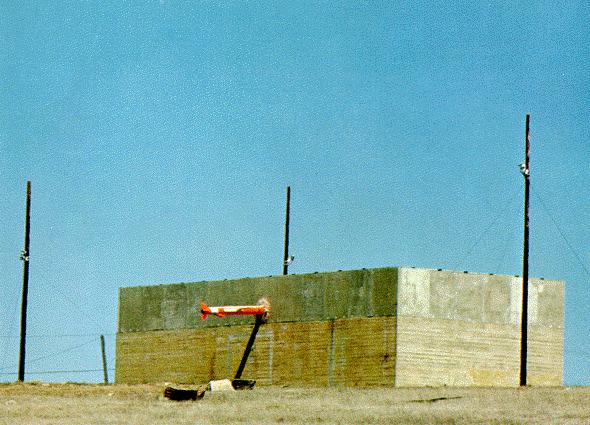

(Inert test missile being fired from USS New Jersey.)

This was actually not the first nuclear weapon for the Iowa class. In 1956, fifty Mk23 16″ shells were built, with a 15kT W23 warhead. It was planned to issue ten to each battleship, plus ten in reserve. In 1957 USS Wisconsin successfully shot an inert example but no live Mk23 was ever test-fired. The Mk23 required a modification to the “B” Mk7 turret’s magazine for secure storage and arming reasons; all but USS Missouri received the modification. There is no indication Mk23s were ever actually deployed on any battleship. In October 1962, the Mk23s were discarded.

The TLAM-N’s primary 1980s mission was simple; if the Soviet navy used tactical nuclear weapons against NATO trans-Atlantic convoys, TLAM-Ns could immediately retaliate from sea against military bases in the Soviet arctic; without an escalation to ballistic missiles. The Tomahawk’s accuracy combined with the warhead’s yield would make it appropriate for use not just against airfields, but command bunkers as well.

The warhead was a 150kT W80 Mod0 design, with a composite uranium & plutonium core triggered by PBX-9502 plastic explosive. Compared to the US Air Force’s W61, the W80 emitted less ambient radiation for shipboard stowage. The warhead weighed 300 lbs, a tenth of the TLAM-N’s total weight. In comparison to the Mk2 “Little Boy” used against Hiroshima during WWII, the W80 Mod0 was 525% more powerful despite being 97% smaller. The warhead was intended for low-altitude airburst and had a PAL (permissive action link) safety system.

(W80 Mod0 nuclear warhead being serviced during the 1980s.)

TLAM-N production ran from 1983 – 1987. In line with national policy, the USA never disclosed how many were made. Most sources feel it was around 300, another figure quoted is 509. Deployment started in 1984 aboard submarines, then later that year aboard battleships.

No complete TLAM-N was ever live-fired but the warhead was detonated twice in Nevada, in 1981 and again in 1982. Inert versions of the missile were successfully fired off all four Iowa class vessels.

There were no problems with TLAM-N in service. The only drawback was they would never be used other than in a nuclear war. Any other time they wasted a slot that could be filled by a conventional-warhead Tomahawk.

In line with policy, the US Navy never disclosed which specific ships carried TLAM-Ns, nor how many were issued per ship. Based on recollections by veterans, battleships carried two or three, although this could be reduced to one or none depending on the mission.

In September 1991, President George HW Bush withdrew tactical nuclear weapons from the US Navy. In the disintegrating USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev made a similar move, which was confirmed in a gentleman’s agreement after Boris Yeltsin became the first Russian president. President Bush’s order came three days before USS Wisconsin decommissioned, and half a year before the last battleship, USS Missouri, left service.

The withdrawn TLAM-Ns were stored at Kings Bay, GA on the east coast and Kitsap, WA on the west. In 2010, President Obama identified the long-stored TLAM-Ns as an item of no further value, and they were scrapped.

TASM

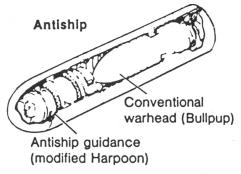

The BGM-109B Tomahawk Anti-Ship Missile (TASM) was a weapon the US Navy never wanted. During the late 1970s, Soviet anti-ship missiles greatly increased in range, meanwhile the US Navy had only the Harpoon. Regardless of naval advice, this was unacceptable to Congress and (spurned on by General Dynamics lobbying) a decision was made to adapt the land-attack Tomahawk airframe into an extreme-range (250 NM+) ship-to-ship weapon.

From the wings on back, a TASM was identical to a TLAM and launched in an identical way. In the front end, the WDU-25 warhead was a 1,000 lbs model based on the AGM-12 Bullpup missile used during the Vietnam War. Ahead of it was a modified Harpoon guidance system and in the nose, an AN/DSQ-28 J-band surface-search radar.

Contrary to public perception in the 1980s, there was no “nuclear TASM”. TASMs could not be fired against land targets. The warhead was often misidentified as “armor-piercing”, in fact it was not, however the fuze was set for a fraction of a second after impact, so that the warhead would detonate inside the target ship. The warhead would also ignite any unused jet fuel inside the TASM.

The TASM’s mission profile was completely different than the other versions. After launch, the missile, guided by inertia, settled into it’s cruise altitude (as low as 8′) until it approached the target ship’s expected location. The missile could be preset to avoid flying over neutral or friendly warships.

At the end of it’s run, the AN/DSQ-28 switched on and began looking for the target. If it was not found, the TASM began “grazing”, making 90° turns, until it found the target. Once found, the radar locked on and dove the TASM into the target’s hull. If nothing was found, it continued “grazing” turns until the fuel ran out.

The seeker was only “semi-smart” in that it could not identify specific warships by class. Thus, if fired at a multi-vessel battle group, it had to be set to either attack the first radar signature encountered, or the biggest, but not both.

The first TASM was tested in 1981. It entered service aboard battleships in 1983. A total of 581 were built between 1981 – 1990.

The US Navy never doubted the results of a hit; a half-ton warhead impacting a ship around 500mph speaks for itself. But even before production started, the US Navy knew it’s biggest problem was going to be finding something to attack at the TASM’s long ranges.

Aboard the refit WWII battleships, the longest-ranged new surface search sensor was the AN/SPQ-9A radar with a range of 20 – 24 NM; the navigation radar had slightly longer range but was not intended for combat. Clearly, third-party targeting would be needed. The assumed set-up was that long-range (over 100 miles) targets would be first detected by a patrol plane like the P-3 Orion; which would relay the findings to an ashore facility or fleet flagship, who in turn would relay the data to the battleship; at which time the captain would make the decision to engage. Obviously all this had to happen very rapidly as the target ship was not sitting still.

As difficult as it sounds, this obtuse set-up might have made some sense for a 1980s submarine. For the battleships, less so. Their primary mission in the 1980s was power projection ashore, not naval duels. For naval combat, each refit Iowa carried sixteen RGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missiles, with a range of 45 – 60 NM. Each battleship’s loadout was in addition to whatever Harpoons might be aboard her escorts. With the exception of an all-out war against the USSR, it’s really hard to look at any hostile navy in the 1980s and imagine a task force that could make it through that kind of onslaught.

In the very unlikely event that a threat somehow made it past sixteen Harpoons and closed within 20 NM, the battleships still theoretically had the option to engage with 16″ gunfire.

Besides the TASM’s targeting hardships, the other dilemma battleship captains struggled with was numbers. Each TASM aboard replaced a TLAM, and typically two or three TASMs at the most were embarked. Against a mediocre flotilla, a half-dozen TASMs might have use. But firing just one or two against a modern threat with good defenses 250 miles away, was unlikely to accomplish anything other than alerting the enemy that they had been detected.

(Test of a BGM-109B TASM during the 1980s.)

The TASM’s range is hard to quantify. During the 1980s, the press lazily just cut & pasted the TLAM’s officially-stated 1,500 miles. This was inaccurate, but the error was fine with General Dynamics who allowed it to be portrayed it as an antidote to the 375 NM-ranged SS-N-19 “Shipwreck”s aboard the Soviet Kirov class. The “Iowa vs Kirov” comparison has been made so many times as to be annoying. In reality the refit battleships were intended as the core of amphibious groups and surface-action groups, not “anti-Kirovs”. For their part, the focus of the Kirov design was interdicting NATO Atlantic convoys and destroying aircraft carriers, not trying to track down and sink a battleship.

Because the TASM flew a much greater part of it’s cruise at low altitude where the air is denser, it’s maximum range was far less. For an average mission, the 1997 edition of Jane’s Fighting Ships quotes 250 NM which is reasonable. Assuming a minimum of five 90° “grazing” turns, the fuel would run out around 380 – 400 NM at the most.

The end of the Cold War in 1991 eroded whatever benefit TASM brought to the fleet. After Desert Storm, some TASMs were rebuilt into TLAMs to replenish America’s Tomahawk inventory. By the mid-1990s, so few TASMs were left that it made no sense to continue training sailors on it. In 1996 – 1997 the entire remaining TASM stockpile was converted and the weapon went extinct. None was ever fired in combat and overall, the whole idea was a waste of money.

TOMAHAWKS OFF IOWAS: OPERATION “DESERT STORM” 1991

The last hurrah of battleships, 1991’s operation “Desert Storm” saw USS Missouri and USS Wisconsin pound Iraqi forces in occupied Kuwait with 16″ gunfire, but also proved the battleship’s worth as a cruise missile platform.

(USS Missouri during operation “Desert Shield” in 1990.)

the opening salvo

President George HW Bush set a deadline of 15 January 1991 for Iraq to fully withdraw from Kuwait, which Saddam Hussein ignored. Privately, President Bush decided to add one “grace day” as a last hope for a diplomatic solution. Not forthcoming, the war would start early in the morning of 17 January in Baghdad, or mid-evening 16 January in Washington.

(Gen. Colin Powell addresses the crew of USS Wisconsin during Desert Shield in late 1990. The popular ‘chocolate chip’ desert camouflage was only briefly-used by the USA and remains an enduring symbol of Desert Storm.) (photo from Life magazine)

USS Missouri and USS Wisconsin were already in the Persian Gulf and already in a wartime posture. The Pentagon already had developed a theoretical concept called “INSTANT THUNDER” combining battleship-fired TLAMs with manned airstrikes, which would destroy between 84 – 100 of an enemy’s key targets in seven days or less. This morphed into the general air war plan for Desert Storm.

The start of Desert Storm was a meticulously coreographed event. There were two milestones in the war’s opening minutes. CP (“Commitment Point”) was the last possible moment President Bush could cancel the war. After this, “H-Hour” was the time when ordnance would start impacting Baghdad.

There would be several prongs from the air. B-52 Stratofortress bombers, flying a grueling mission out of Barksdale AFB, LA that started 17 hours earlier, would fire long-range ALCM missiles. AH-64 Apache helicopters would fly a “blinding” mission against radars on Iraq’s border. F-117 Nighthawk stealth fighters would hit Baghdad, as the first shipboard Tomahawks arrived.

(F-117 of the opening strike being refueled while still in Saudi airspace. The little stealth planes were the only manned types in the first Baghdad package, the remainder being Tomahawk missiles.)

At 01:30 local on 17 January, the B-52s passed their last recall point and the Apaches took off under radio silence. This was CP, there was now no way to stop the war.

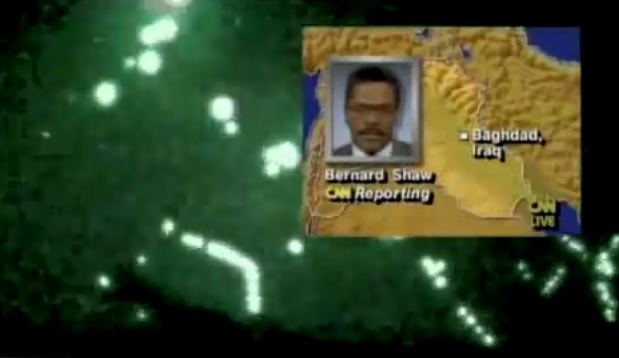

(USS Wisconsin’s captain in the battleship’s Combat Information Center (CIC) during Desert Storm. USS Wisconsin was the overall Tomahawk coordination ship.)

At 01:41, the destroyer USS Paul F. Foster (DD-964) began launching Tomahawks, followed less than a minute later by USS Missouri. The firing order in the fleet was determined by the location of ships, to coordinate missile arrivals on target. At 02:15, USS Wisconsin began launching Tomahawks.

(Time-lapse photo of one of USS Wisconsin’s opening shots.)

(As readers of a certain age probably remember, Desert Storm ‘started’ at dinnertime in the central USA, while nightly news broadcasts were in progress. Nobody knew as Peter Jennings began his newscast that night that Tomahawks had already been in the air for some time, quietly on their way to Baghdad.)

(Another Tomahawk departs USS Wisconsin on it’s way to Baghdad.)

At 02:38, the Apaches (having flown a few feet over the Saudi desert to evade detection) arrived at their target and began blasting Iraqi long-range radars at point-blank range. At 02:51, F-117 Nighthawks took out radars deeper in Iraq. The goal of the Apache and Nighthawk missions was to create an “electronic tunnel” through the Iraqi air defense system, for non-stealth jets to fly through later.

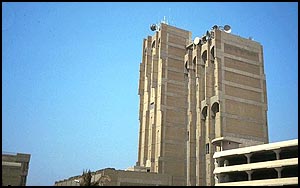

At 03:00, “H-Hour”, the stealth F-117 Nighthawks arrived undetected over downtown Baghdad and began dropping bombs on key targets. About a minute later (the delay was intentional, to avoid explosions distracting the stealth pilots), the battleship-fired TLAMs arrived, also undetected.

(Baghdad’s International Telecom was hit by both Tomahawks and F-117 jets. American servicemen nicknamed it “The AT&T Building” and some newspapers erroneously reported that it was owned by that American company.) (photo via Washington Post newspaper)

(Taken from a F-117 Nighthawk, this shows the “AT&T Building” exactly at H-Hour, 03:00, moments before it was hit.)

Iraq’s anti-aircraft network was judged the third-largest in the world in 1991, behind the USSR and North Korea (the USA having long since abandoned domestic AA defenses). As the war started in the middle of news broadcasts, reporters in Baghdad’s luxury hotels showed AA defenses firing wildly into the night.

Iraq’s AA assets ran the gamut, from WWII guns, through more modern Cold War guns and SAMs, plus some high-end SAMs. Central Baghdad was extremely protected and had more AA weapons per square mile than anywhere else on Earth.

(The 61-K was a widely-used towed AA gun of the Soviet army during WWII, later exported to Iraq. It fired the 37x250mm(R) cartridge and was manually aimed and manually operated. A WWII gun like this had zero chance of shooting down a Tomahawk. This one was abandoned in Kuwait in February 1991, probably in haste as it still had a loaded magazine.)

(A more modern Iraqi asset was the Soviet-made ZSU-23-4 tracked AA system, which had four 23mm autocannons guided by a flip-up radar dish. This one was captured during Desert Storm and delivered to Rock Island Arsenal for exploitation. The USA suggested that one TLAM had been shot down by a ZSU-23-4.)

(The SA-3 “Goa” SAM served Iraq against Iran in the 1980s and in both the 1991 and 2003 conflicts against America. To oppose cruise missiles, SAMs have a speed, range, and accuracy advantage against AA guns, but they also have problems at low altitudes and require off-mount radars. “Goa”s shot down a F-16 Falcon during Desert Storm, and possibly a Tomahawk.)

the war continues

After the opening volley, both battleships resumed Tomahawk launches later in the morning of 17 January, then again later that night into the 18th.

(A Tomahawk departs USS Wisconsin after sunrise.)

(During one volley, USS Wisconsin was launching Tomahawks five seconds apart. Here they are shown doing their initial ascent, then descent to cruise altitude where the boosters would separate.)

(USS Missouri fires a TLAM on the war’s second night.)

(The missile climbs away from USS Missouri on it’s way to Iraq.)

A high proportion of the missiles fired from both battleships came towards the start of the war. A total of 116 Tomahawks were fired in the first 24 hours, off the two battleships and five other vessels. USS Wisconsin fired 24 of the 32 Tomahawks carried aboard in the first day and a half alone.

(A Tomahawk being fired against Iraq from one of USS Wisconsin’s aft ABLs.)

The targets were varied. Most TLAMs were fired at communications assets, electricity plants, suspected chemical weapons depots, and “leadership targets” of Hussein’s regime. Four individual missiles were fired at what was described as “oil-related targets” and three individual missiles against Iraqi AA defenses. All of these were BGM-109Cs, the unitary warhead model.

(The Baghdad HQ of Iraq’s military intelligence service, nicknamed “the Biltmore Hotel”, was hit.) (photo via Washington Post newspaper)

(The Iraqi Defense Ministry was hit hard in 1991. It’s replacement was hit by Tomahawks in 2003.) (photo via Washington Post newspaper)

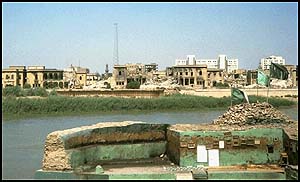

(Urban bridges, like this one over the Tigris in downtown Baghdad, were hit. This was initially puzzling as they didn’t bear much military traffic. It’s now known that the CIA learned that Baghdad’s air defense network was linked together by telephone lines; these were carried over the Tigris in conduits underneath bridges as opposed to underwater cables. The bridges were dropped to sever the lines, not to disrupt military logistics.) (photo via Washington Post newspaper)

(A Tomahawk departs USS Wisconsin during daylight on 17 January 1991.)

As the war progressed, a number of BGM-109Ds, the submunitions model, were fired off the WWII battleships. These were targeted at Iraqi air force bases and intended to destroy any warplanes out of their shelters, along with runway support vehicles.

(USS Missouri firing a Tomahawk on 18 January.)

(One of the last Tomahawks fired off USS Wisconsin departs.)

Of all the TLAMs combined off all ships and submarines, 39% were fired within the first 24 hours of the war (many in the big opening salvos off the battleships), 62% within the first 48 hours, 73% in the first three days, and 98% within the first two weeks. The last Tomahawk mission was on 1 February 1991, when a half-dozen BGM-109Ds were fired against al-Rasheed airbase in a daylight raid. This was one of the least successful Tomahawk missions, with only two of the six making it to target. After this mission, Gen. Norman Schwartzkopf forbade further TLAM firings off the battleships. Schwartzkopf (who passed away in 2012) never revealed why in any unclassified setting. One theory is that he wanted the two battleships to concentrate on destroying Iraqi ground assets with 16″ missions. But there was no technical reason why the Iowa class could not simultaneously fire Tomahawks and 16″ guns, so a more pragmatic possibility is that he was looking at the big picture…..BGM-109s were expensive, in limited supply, and giving diminishing returns by February; and the USA might have other needs for cruise missiles after the conflict.

Desert Storm ended on 28 February 1991. USS Wisconsin had fired 24 TLAMs and USS Missouri, 27. USS Wisconsin was also the overall Tomahawk coordination flagship for all ships and submarines using the weapon.

assessments

The USA’s Department of Defense stated later in 1991 that Tomahawks destroyed 18 targets and either partially destroyed or damaged another 16. This is a total of 34 targets, which differs somewhat from the US Navy’s total of 38 targets engaged with Tomahawks. The term “target” is broad, there were 174 separate coordinates loaded into TLAMs.

During the war, the US Navy had loaded 307 missions into TLAMs. Of these, 19 were scrubbed before launch due to technical problems. Of those 19, sailors rectified the problem on 10 missiles and they were used later in the war. The remaining 9 were defective weapons.

Of the 288 missiles thus successfully launched, 6 are known to have failed in-flight. In every case the cause was failure of the spent booster rocket to separate and/or the wings and tail to deploy, to enable normal cruise flight.

Of the 282 Tomahawks that thus launched and transitioned to cruise, it was publicly stated that “85%”, or 239 missiles, arrived on target, which is not the same as destroying it. One notable case was the GHQ of Iraq’s air defense command in Baghdad; a structure designed by Yugoslav architects in the 1980s with an 11′ thick roof. Two Tomahawks scored direct hits yet failed to damage it.

Of the remaining 43 missiles, 30 were intentional airbursts of BGM-109Cs and impossible to confirm, and 13 were called “no-shows”. Of the “no-shows”, it is thought that for certain one, probably three, and maybe a half-dozen, were shot down, all by ground fire. One is thought to have been shot down by a ZSU-23-4 self-propelled AA gun. One was possibly downed by a SA-3 “Goa” SAM. The SA-2 “Guideline” is known for certain not to have hit any. The loss of the remaining “no-shows” is to AA weapons unknown. No Iraqi fighter jets engaged a Tomahawk air-to-air.

(Ascent of a BGM-109 of USS Wisconsin during Desert Storm. The initial launch was usually the highest it flew.)

In June 1997, the Government Accounting Office (GAO) re-evaluated the performance of weapons used during Desert Storm in 1991. The public version of the report was redacted but indicated the success of the TLAM was less than the advertised “85%”. It was noted that damage assessment was hard as some targets had been hit by both TLAMs and manned aircraft. On the other hand, the numbers did not show “intangible” benefits, such as a Tomahawk taking out one command post which then enabled manned jets to attack multiple targets later.

In any case, the battleship-launched Tomahawks were an important asset. For most of the conflict, TLAMs were the only weapons used against targets in the heavily-protected AA core of downtown Baghdad during daylight, and along with the F-117, were the only systems used at all there in the first days. On a per-capita, per-mission basis, the success rate, however measured, was as great or greater than any manned plane other than the Nighthawk, and without risking pilot lives. As for the battleships, the combination of long-range missiles and powerful short-range guns was a unique combination in the Gulf.

postscript

For those interested in naval history, the allure of battleships will always be the big guns. Certainly during the latter part of Desert Storm, USS Wisconsin and USS Missouri made tremendous use of their 16″ guns. However in the last days in the history of battleships, the Tomahawk was also a key weapon.

(USS New Jersey mothballed at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in 1993. All four Iowa class battleships would later be made into museum vessels.)

Reblogged this on Brittius.

LikeLike

Course, we could have put those missle launchers on anything. Even a barge. But how cool would that of been?

USA: we still have SEVEN battleships.

Rest of world? none.

BOOM.

LikeLike

It was suggested in Congress to reactivate one cruiser, USS Des Moines, to fulfill both the gunnery support and TLAM mount missions; instead of the four battleships.

LikeLike

My favorite story about the reactivation is this. In the original Iowa class design the area amidships was meant for ships boats storage. The rails for that were placed but none of the ships carried boats there. Instead the 40mm and 20mm tubs/gallerias were placed on top. In the 1980’s when all the remains of those were removed those rails were found still to be there. The base for the ABL’s was placed on top of them. Great read thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Probably more than any other single project, the reactivation of the 4 battleships sums up how rediculous military spending got during the waning years oc the cold war. Great article.

LikeLike

That is not the case. The reactivation of the Battleships was a spectacular success–in both visible and less visible ways. Battleship Battle Groups could (and can) perform many, while not all, of the missions of Carrier Battle Groups–at considerably less cost.

The Navy botched some aspects of the reactivation. But it was still successful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thats a bold statement, seeing as how the Japanese tssted that theory during WW2 and found it to be completely false.

LikeLike

As a minor footnote on this article, in 1978 adventure fiction writer Clive Cussler bought out the novel

Vixen 03, which he set in 1988, a major element of the plot is that the novels ‘bad actors’ take over the shipyard where the USS Iowa is being scrapped (The USS Wisconsin having being scrapped in the novels 1984.) and modifying it so that they can sail it up the Potomac and bombard Washington DC.

If nothing else it shows what people were expecting to happen to those four battleships in the late 1970s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was a tour guide aboard Iowa for a couple of years, and am very interested in the history of the class. I’d never heard about the plan to reactivate only one turret, or to man the turrets with reservists. Where did you find that from? I’d love to see the original source.

And also, I really like the blog. Fascinating stuff, and great photos.

LikeLike

An issue of Proceedings from 1980 (I dont recall which month) briefly mentioned the rotating reservist concept. There was a NY Times article in 1982 which alluded to the fact that the Navy only wanted them as TLAM launchers and while they realized that the core of support in Congress was for the offshore gunnery.

LikeLike

Thanks. I found what I think are the NYT articles online, and I’ll look through the Proceedings archive soon.

LikeLike