(A Kingfisher scout plane catapults off the cruiser USS Detroit (CL-8) during WWII.)

(Abandoned Kingfishers lay in a US Navy storage lot in 1946, a year after WWII ended)

Because most photos of battleships concentrate on the inter-war and WWII era, it’s generally assumed that catapults and seaplanes were always a fixture on them, but this isn’t accurate.

If one considers the “battleship era” starting with the Spanish-American War in 1898 and ending with the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941 , it was only half a century that that this type of warship ruled the seas. Of that, seaplanes aboard battleships had an even shorter run, about 24 years. For context, there were US Navy sailors who enlisted before battleship catapults existed and retired after they were already gone.

The first US Navy catapult was the Type A Mk1, which was designed in 1921 and tested with a Curtiss N-9 at Philadelphia Navy Yard.

It entered fleet use in 1922, initially on the Tennessee, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania class battleships. These old classes all had a sharp transom with the catapult being sited at the extreme stern, which would remain the preferred location in the US Navy.

(USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) in the 1920s with a pair of Vought UO-1 planes on a Type A catapult. The UO-1 was an offshoot of the VE Bluebird, the US Navy’s first carrier-based fighter.)

Development in other countries followed a similar timeline. IJN Nagato received the first Japanese catapult in 1925 but it was not until the early 1930s that they became standard on Japanese battleships.

(The Aichi E16A1 “Paul” was an Imperial Japanese Navy catapult plane of WWII. Two kokutais, the 634th (afloat battleships) and 801st (ashore) flew it. This one was studied by the US Navy after WWII.)

The British navy employed crossdeck amidships catapults. These were less ideal than the American set-up, but because seaplanes of these navies were heavier (the Royal Navy’s Walrus Mk.I required a launch force of 4 tons) there was no option, until years later when a suitable turret-top model was made. The Soviet navy’s Gangut class battleships could not mount a catapult of any type because of their odd layout, but the Kirov class cruisers had one of the trainable style.

US Navy catapults were designated by a letter denoting how they worked: A for compressed air, H for hydraulics, F for flywheel, and P for gunpowder.

The A (compressed air) type worked well, but the main issue was that the space-consuming flasks had to be recharged by a compressor after each launch. The P type was determined to be optimal for battleships.

In 1923, the Type P Mk3 was tested aboard USS Mississippi (BB-41). It could accelerate a 3-ton mass from 0 to 55 kts in a 20-yard span. It was also the first with a blast diffuser which enabled much more powerful charges to be used. At the same time, the US Navy sought to double the aviation abilities of battleships by siting a second catapult atop a turret (usually the “X”, or upper aft). USS Mississippi was also the first with this.

(USS Arizona (BB-39) visiting Seattle, WA in 1940 with a second, turret-top catapult installed. On turret-top installations, the front of the catapult faced the turret’s rear. Today many scale models, etc incorrectly portray it as if the plane launched over the gun barrels.)

Turret-top catapults did not (contrary to some modern accounts) impact the gun fields of fire, but were more of a hassle then they were worth. Throughout WWII, the US Navy eliminated many of them. Other navies did as well, for example the German Scharnhorst class had their turret-top catapults deleted in 1939-1940. Exceptions in the US Navy were USS Arkansas (BB-33), USS Texas (BB-34), and USS New York (BB-35); because of their layout these elderly battleships had no other option.

(WWII Omaha class cruisers carried catapults on elevated towers. This was far less ideal than the stern deck arrangement on battleships, but because of the class’s layout there was no option. In this photo the catapults are being upgraded from Type P Mk1 to Mk5.)

The Omaha class cruisers were the first American warships designed from the outset with catapults, carrying two, initially of the Type P Mk1 version. The Maryland class were the first battleships designed for planes from the outset.

In 1929, the Type P Mk6 was developed. It could accelerate a 3¼-ton mass from 0 to 61 kts in a 20-yard span. This was the supreme design. As funding permitted, the Type P Mk6 replaced older types on existing warships. From USS North Carolina (BB-55) onwards all new US Navy battleships were built with it from the start.

(This Kingfisher was assigned to USS Quincy (CA-39), later sunk in WWII. It shows the pre-WWII marking scheme with colored squadron band on the fuselage and the national emblem on the engine. The ID bands were abandoned during WWII and the emblem moved back to the fuselage. The red dot in the star was later deleted as during high-speed combat, it looked like the Japanese rising sun.)

US Navy shipboard seaplanes were organized into squadrons of 14 planes. Between two to five planes of the squadron was then assigned to individual ships. In the 1930s, the roofs of battleship turrets were painted in an identifying color for pilot’s benefit. Some of the battleships sunk at Pearl Harbor still had painted roofs in 1941.

US Navy training was done at NAS Jacksonville, FL and NAS Pensacola, FL. As WWII progressed another training facility opened at NAS Corpus Christi, TX. Future catapult pilots started off on the N3N Canary biplane.

(N3N Canary)

Intermediate and advanced training was done first with surplus SOC Seagulls and later, OS2U Kingfishers as they became available. Besides launches off an ashore catapult, this phase included dogfighting, dive-bombing, and crane hoist training.

(Ashore training catapult and crane during WWII.)

(Kingfishers assigned to a training squadron.)

(A Kingfisher makes a firing pass at a towed target sleeve during WWII.)

Finally, just before heading to battle, catapult pilots trained aboard USS Absecon (AVP-23), a specially-configured warship with two Type P Mk6 catapults and battleship cranes that did nothing but train aviators out of NAS Port Everglades, FL.

(USS Absecon operating the hated Seamew, which was already being relegated to trainer use by 1943.)

Foreseen uses and disadvantages

During the US Navy’s grand Fleet Problem I – XXI wargames between 1923-1940, a fine-tuned set of missions was envisioned for battleship seaplanes. They were”scout”, “bomber”, and “fighter” which did not match traditional definitions. “Scout”s were to localize an enemy’s battleship line and determine an optimal course for friendly battleships to “cross the T”. The “bomber”s were not intended for traditional attacks, but rather to sink weak ships so battleships did not have to waste time breaking formation, or expend ammunition (During the 1930s, 14”-caliber accuracy rates above 9% were considered phenomenal). Finally, “fighter” missions were not to defend the fleet, but rather to chase down and eliminate enemy scouts before they could report, as aircraft radios were not yet universal.

The Fleet Problem exercises disproved the tactics they were supposed to refine. Especially during Fleet Problem V in 1925, USS Langley (CV-1) showed that an aircraft carrier could fulfill these missions superior to battleship-launched seaplanes. Instead during WWII, the main roles of battleship seaplanes became bombardment gunfire spotting, rescue, and anti-submarine warfare (ASW).

Tactically, a captain had to balance the benefit of a seaplane flight with the difficulty of launching and recovering it. At a minimum, course and speed changes would be required, and usually an escorting frigate was pulled off-station in case the plane wiped out and the aircrew needed rescue.

The biggest danger of aircraft on surface combatants was fire. Aviation fuel is extremely flammable and it’s fumes explosive. The avgas tanks were armored and deep inside the ship, but there still had to be a fill & feed pipe up to the weather deck. (On older American battleships, the avgas tank was in the extreme bow, with the pipe running external to the hull armor the length of the ship.) The planes themselves, and their hangar, were filled with fuel and ammunition and a hazard during a surface battle.

(Hangared SOC Seagull with it’s wings folded. Catapult plane hangars were miserable. Extremely cramped, they stank of fuel and mildew. In bad weather the roof often leaked terribly, while in good weather the hangar baked like an oven.)

One of the reasons the US Navy favored catapults at the extreme stern was so that a fire could only spread in one direction. The launching gear was another danger, as the restraint lines used doped fiber and the catapults used 5″ blanks.

These blanks presented a danger. The cause of USS Arizona‘s loss on 7 December 1941 was a Japanese bomb exploding seaplane catapult blanks which in turn detonated one of the forward 14″ magazines.

The Type P Mk6 catapult

This was the definitive model. A total of 165 were built for the US Navy, all by the company Koppers. The steel catapult itself was 65’x5′. It was rotated by an electrical motor that interfaced with a toothed gear on the ship’s deck.

The plane did not rest directly on the catapult, but rather on devices called cars.

(Type P Mk6 launch car.) (official US Navy diagram)

The launch car’s underside had “shoes” of synthetic resin which glided along the top of the catapult. Extreme care was needed to keep both the shoes and the catapult’s bearing surface clean. When the seaplane was revving prior to launch, a pair of steel pins acted as a safety. These were retracted prior to firing the 5″ blank. The jolt to the car was cushioned by a pair of buffers.

The plane’s center float rested on a rear padded saddle, secured by steel J-hooks. Saddles could be taken on and off the cars as needed as newer seaplane types came into use.

(Seahawk leaving a battleship’s catapult, the launch car has just struck the brake pistons.)

At the end of the catapult was a pair of cylindrical braking pistons which stopped the car’s forward movement.

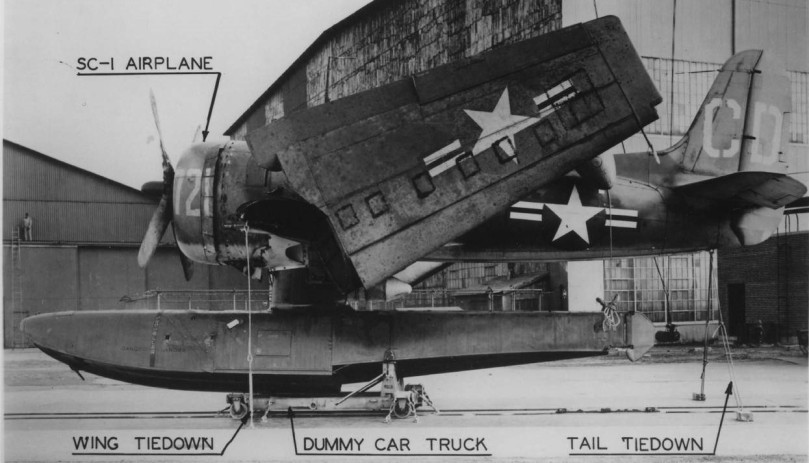

There were also dummy cars. These had no launch features, but allowed multiple seaplanes to be stored on one catapult. They were also wheeled so sailors could manhandle planes on the battleship’s deck.

The Type P Mk6’s dummy car was also useful for moving seaplanes ashore, as seen below.

Launch

To launch a seaplane, it was set on a launch car. The catapult was trained 30°-45° outboard, and the ship turned into the wind. If that was not possible, sometimes a cross-deck launch was done, but only if there was no other option. A 5″ blank was loaded into the “gun”.

(Loading a 5″ blank into the catapult’s “gun”.)

While a signalman on deck held up a red flag, the pilot revved the engine to maximum power. If all was good, the pilot gave a thumbs-up (there was no intercom system). After the thumbs-up, the seaplane pilot was then at the mercy of the ship. The signalman then gave a green flag and the catapult was fired.

(USS Missouri (BB-63) launching a Kingfisher during WWII. The chief on the right is covering his ears, as the combination of the plane and the 5″ blank was tremendously loud.)

If the ship was rolling, the launch had to be timed for waves setting the deck at an even keel. In a trough, the plane would otherwise obviously slam into the ocean, while in a heave the added angle might cause it to be going too slow leaving the catapult.

The 5″ blank “gun” had an artillery-style breech. Part of it’s firing combustion was diffused by a perforated steel cylinder. The rest moved a crosshead attached to a piston, which operated the steel cable that yanked the launch car.

As the plane left, it immediately fell in altitude a bit. The pilot had to be very skilled; he needed to gain altitude quickly but also could not pull up the nose, or the wings would go into stall.

Recovery

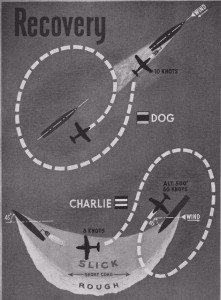

By far, recovering the seaplane was the most difficult thing of operating them, both from tactical and safety standpoints. Before, during, and after WWII, the US Navy had four protocols:

Able: This was used only when a ship was anchored. The seaplane landed wherever it wanted, cut it’s engine, and waited for a smallboat to tow it under the ship’s crane.

Baker: This method was used when a ship was moving straight and slow in calm seas. It was similar to Able except the pilot had to taxi the plane underneath the crane, taking care not to strike the ship with his wingtip.

Charlie and Dog: By far the most complicated method, this was also the most-used in WWII as there was rarely the luxury of calm waves. First, the ship executed two 45° turns. This “ironed out” a comparatively smooth patch of sea, called a lee. If the tactical situation allowed, the ship threw a smoke flare into the lee so the pilot could judge wind direction at sea level, which often differed from his approach altitude. The pilot landed in the lee, then taxied across it to catch up with the mat being towed by the ship. (Dog was even more dangerous as it required the pilot to land in the ship’s wake.)

(SOC Seagull making a “Charlie” landing during WWII, note the difference between the lee and open ocean.)

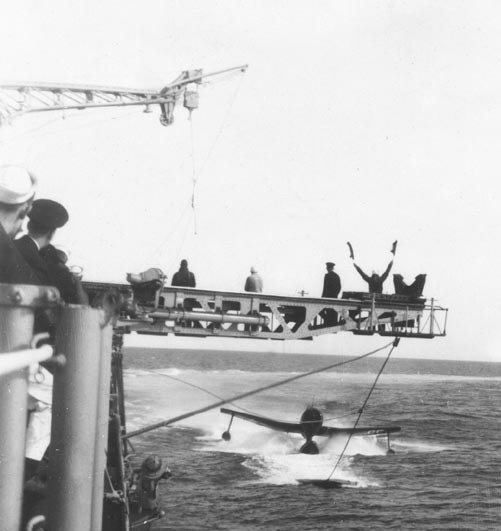

The mat itself was a wood or aluminum crosspiece covered in canvas, followed by a 20’x10′ rope net. The forward part was slightly curved, like a toboggan. Underneath was a pair of mini-rudders set on an angle to keep the mat in the correct position. A wire towed it, and there was a separate rope called the breastline that kept it in the desired location. A sailor with a fire ax was stationed at the breastline, in case the plane’s outrigger float entangled it, to prevent the plane from being dragged under the ship. To utilize the mat, the seaplane taxied a bit faster than the ship was traveling (ideally, 8 kts), taking care to run over the mat with the center float but not overshoot it and snare the tow line in the propeller.

(Landing mat used by a Seahawk of USS Alaska (CB-1) near the end of WWII.)

Underneath the plane’s center float was a hook with a one-way spring. As the float rode up the mat it sat flush. When the pilot was satisfied, he cut the engine and as the plane lurched back, the hook snagged the mat.

(A Seahawk lands in the lee of USS Little Rock (CL-92) near the end of WWII. The cruiser turned the catapult 90º so a signalman could walk out onto it, in line with the towed mat. Seaplanes sat high and as the pilot neared the mat, it was hard to see it past the plane’s nose.)

From there, the pilot quickly exited the cockpit and manually attached the crane. This had to be done with expediency, as the aircraft would be in danger if it came unsnagged off the mat.

(A Seahawk pilot attaches the crane to his plane, it’s engine shut off and being dragged by the mat.)

The crane style used on the North Carolina and later classes had a 3-ton capacity which was sufficient for any US Navy catapult seaplane. It was 18’10” tall above the weather deck. The crane could be in it’s normal raised position, “knuckled down” to allow the crew to maintain the hook and tackle, or laid prone for gun battles. When prone it rested on a spring bumper. The working parts of the crane were inside the battleship. One deck below was the motor to rotate the crane, and a deck below it the cable winch and reel.

(Excellent view of the standard WWII-style crane, here aboard USS Birmingham (CL-62) during a visit to Australia.)

With a seaplane in hand, these cranes could move 180° per minute. They could rotate 500° in either direction so that multiple loads on one side of the ship could be lifted to the other without backing the crane back around. A final touch was an overhead light.

(The crane’s controls were very simple, as seen here aboard USS New Jersey (BB-62) after WWII ended.) (photo by Pieter Bakels)

Hoisting the plane back aboard was not easy. It had to be stopped from spinning. This was accomplished by long padded poles operated by the ship’s sailors, as seen below aboard USS Pennsylvania (BB-38).

While suspended in the air, any number of problems could happen. If the plane wasn’t kept left/right level, one outrigger float might contact the ocean with the below result.

Finally the plane was hoisted over the deck (itself a challenge in high winds or while rolling in waves) and sat down on either the launch car on the catapult, or a dummy car on deck.

(USS Nevada (BB-36) lifts a Kingfisher back onto the launch car towards the end of WWII.)

As dangerous as the mat system was, this crude device was a tremendous advancement by the US Navy. Other navies operating catapult seaplanes had it even worse.

(During WWII, the German navy lacked anything like the US Navy’s landing mat. Here an Arado Ar-196 hooks onto the crane. The pilot had to then taxi it at a speed constant with the ship, in a straight line, until the exact moment the crane took it’s weight, when he cut the engine.)

LAST OF THEIR KIND: The US Navy’s final catapult seaplanes during and after WWII

the Curtiss SOC Seagull

(Seagull operations before the landing mat was invented.)

Introduced in 1935, these trusty biplanes were in widespread use at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack. The were used throughout WWII and a few were still aboard old cruisers at the end of WWII. A total of 322 were manufactured. The 2-seat Seagull was 31’5″ long with a 36′ wingspan. The wings could fold for storage. The engine was a Pratt & Whitney R-1340 and the top speed was 116 kts. There was a forward-firing M1919 .30-06 machine gun and a second operated by the rear crewman. Two small depth charges or bombs could be carried.

(SOC Seagulls aboard USS Denver (CL-58) near the end of WWII.)

(The Seagull could carry two Mk17 depth charges for anti-submarine missions.)

The Seagull was already off battleships by the end of 1941 and was supposed to have been replaced altogether in 1943. However the failure of the Seamew meant these biplanes served on until 1945.

the Vought OS2U Kingfisher

This was the main US Navy catapult plane throughout WWII and after. A total of 1,519 Kingfishers were manufactured, making it the most-built plane of this type in any era by any navy. The first were delivered in August 1940 to USS Colorado (BB-45). Production ended in late 1942.

(Kingfishers aboard USS Missouri (BB-63) during WWII.)

The OS2U had a length of 33’10” and a 35’11” wingspan. It was powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-985 engine with a top speed of 143 kts. There were two pylons for depth charges or bombs, a forward-firing M1919 .30-06 machine gun and another M1919 operated by the rear observer. The pilot had a tubular dive-bombing sight with a dogfighting gunsight on top of it. The floats could be replaced with temporary wheeled landing gear.

(The rear M1919 folded down so the canopy could close over it during non-combat flight.)

(The Kingfisher’s elaborate radio gear.)

The OS2U was designed for any catapult still in use. Besides shipboard use, ten ashore squadrons flew Kingfishers during WWII. Some also served with the US Coast Guard during WWII, and one US Marine Corps squadron (VMS-3) flew Kingfishers.

Submarines played a bigger role in WWII than had been envisioned during the 1930s, and the Kingfishers made ideal anti-submarine warfare (ASW) mounts. On 15 July 1942, Kingfishers sank U-576 in the Atlantic. On 19 August 1943, Kingfishers in the Pacific sank IJN I-17.

(Mk41 depth charge, carried by Kingfishers during WWII. By replacing the hydrostatic fuzes with impact models, it could be dropped as a regular bomb against land targets. This weapon remained in US Navy use after the war, into the 1950s.)

A critical, maybe it’s most important, WWII role which the Kingfisher fulfilled with excellence was search & rescue. The most famous Kingfisher-rescued survivor during WWII was Cpt. Eddie Rickenbacker, the legendary US Army ace of the previous world war.

(Kingfishers being trucked overland. During the Japanese invasion of Alaska’s Aleutian islands, squadron VS-56 dispersed it’s seaplanes from NAS Adak, AK to a remote lagoon.)

One feature the Kingfisher introduced was wingtop spoilers. After launch from a catapult, previous seaplanes had a hard time being stable as their low speed in the critical first few seconds moved insufficient air over the control surfaces. By popping these spoilers up and down on one or the other wing, the pilot could maintain control while still building airspeed.

Overall, the OS2U was an excellent plane which served in every major Pacific battle, from Pearl Harbor to Okinawa.

(Kingfishers aboard USS New Mexico (BB-40) during the final months of WWII. This photo shows the seaplane limitations of the old-style battleship hull layout. The rear turret had to be slewed to use the catapult at all, and the aft deck was barely big enough to handle a second plane.)

the Curtiss SO3C Seamew

An intended replacement for the SOC Seagull (the US Navy initially planned on calling it Seagull as well), this was one of the worst American warplanes of WWII. The two-seat SO3C was 36’10” long with a 38′ wingspan. It was armed with a forward M1919 .30-06 machine gun and a M2 Browning .50cal for the rear crewman, along with two depth charges. The engine was a Ranger V-770-8, an uncommon type which often overheated. The top speed was just 149 kts, only 33 kts faster than the biplane it replaced.

The SO3C had severe flaws. Lateral stability was poor, so a swollen fillet was added under the tail. If the rear crewman opened the canopy to fire his M2, the fillet not only lost all effect but made the instability worse. If the nose balanced too high at launch, the ailerons stopped working, preventing the pilot from pitching back down. To alleviate this, the Seamew was often flown with only 27% fuel, making it useless as a scout.

SO3Cs were issued to American warships in late 1942, with the cruiser USS Cleveland (CL-55) being first. The RAF ordered 250 of the wheeled version (designated Seamew Mk.I), of which 100 were delivered before shipments of the hated “Sea Cow” were halted. In 1943-1944, the US Navy pulled SO3Cs off frontline warships. To compensate, SOC Seagulls which had been withdrawn to training were reissued to the fleet, and the SC-1 Seahawk project was accelerated.

the Curtiss SC-1 Seahawk

The Seahawk was the pinnacle of all battleship aviation designs. Entering production in 1944, it was based on experiences of all earlier types. A total of 512 were manufactured in 1944 and 1945. USS Guam (CB-2) was the first warship to operate Seahawks.

(Seahawk of USS Alaska (CB-1) near the end of WWII.)

The Seahawk was 36’4″ long with a 41′ wingspan. It had folding wings, designed in a clever way that neither wing nor outrigger float protruded past the tail’s height or width.

(US Navy guide to weather-stowing the Seahawk, here on an ashore training catapult. An AN/APS-4 is under the right wing.)

It was convertible to either floats or wheeled landing gear. The SC-1 was powered by a supercharged Wright R-1820 Cyclone and had a top speed of 272 kts, with a 37,300′ ceiling. The Seahawk was a single-seat design but there was a small hatch so that rescued survivors could climb inside the fuselage and ride to safety.

The armament was two M2 Browning .50cal machine guns, and the Seahawk was fitted with a fighter-style deflection gunsight. Additionally there were two underwing pylons that could use any ordnance carried by any previous seaplane type, or 60-gallon drop tanks.

(The Seahawk’s fighter-style cockpit.)

The Seahawk was wired for the AN/APS-4 radar pod. This immensely useful item was carried in place of one external bomb on a variety of US Navy planes. If not needed, it could be removed and another depth charge carried instead. For the Seahawk’s scout mission, it greatly expanded the area one aircraft could search. On the home front, there was no need to coordinate radar production with airframes. The very effective AN/APS-4 continued in use long after WWII.

The biggest criticism of seaplanes amongst WWII battleship captains was their inability to be recovered in rough weather. To address this, the Seahawk was rated to land in 25 kts surface winds and 5′ waves.

The center float attachment was semi-flexible to enable hard landings in rough seas. An unusual feature was a compartment in the main float which could be used as a bomb bay, cargo area, or additional fuel tank. After time this tended to leak and many battleship captains ordered it sealed shut for fuel use only.

The SC-1 had a high loss rate, but this was not due to any design flaw. In fact it was almost the opposite – the design was so high-end, it was used for many dangerous missions in terrible weather which would not have even been contemplated with earlier seaplanes.

post-WWII “could-have-been’s”

the Colombia XJL-1

(photo from All Hands, the US Navy’s magazine)

This plane was designed by Grumman during WWII but was handed off to Colombia Aircraft to allow Grumman to concentrate on fighters. The XJL-1 was unique, intended to be a battleship catapult scout, ashore amphibian, and carrier-based scout. Besides floats for battleship use, it had standard landing gear for runway operations plus an arrestor hook and launching bridle point for carrier use.

The XJL-1 was intended for every imaginable use: scouting, ASW, gunfire spotting, rescue, medevac, aerial photography, training, and staff transport. It was powered by a 1,350hp Wright R-1820 piston engine and had a top speed of 104 kts. It was 45’11” long with a 50′ wingspan.

For reasons totally unclear, this project survived the US Navy’s 1945 budget slaughter after Japan’s surrender, even as more urgent systems were cancelled. The prototype was used for ground tests. The second and third XJL-1s were completed in 1946 and sat idle most of that year. Astonishingly, at the same time the Navy progressed towards helicopters, Congress renewed XJL-1 funding for another year. In 1947, the two remaining planes were tested at NAS Patuxent River, MD. After all this, in the end the US Navy rejected the type. The many mission requirements were simply too much to squeeze into one airframe.

the Edo XOSE-1

This was the final catapult seaplane. It was a product of Edo Corporation’s College Point, NY factory which was a subcontractor for other manufacturers during WWII. In 1945, they attempted their own plane.

The single-seat XOSE-1 was 31’10” long with a 37’11” wingspan. It was powered by a Ranger V-770-8 engine (the same as in the failed Seamew), set upside-down. The ceiling was 22,300′, a full 10,000′ less than the Seahawk.

Edo’s concept was completely opposite to Colombia’s, in that the XOSE-1 was a dirt-cheap plane suitable for basic missions only. It had two M2 .50cal machine guns and pylons for a pair of WWII-era depth charges. It had, as an option, underwing pods that rescued survivors could ride in.

Despite it’s beautiful appearance the XOSE-1’s top speed was 172 kts, 100 kts slower than the SC-1 Seahawk and only 29 kts faster than the old SOC Seagull biplane. The US Navy ordered ten as a fall-back option if helicopters, for whatever reason, proved unsuitable.

Perhaps the XOSE-1’s “highlight” was when one blew an engine and made an emergency landing on NYC’s East River. Clearly it was unsuitable for the Cold War and the project ended in 1947.

END OF THE ROAD – CATAPULT AVIATION AFTER WWII

(A Seahawk operational at NAS Jacksonville, FL one year after WWII ended.)

Even before WWII ended, the writing was on the wall for catapult aviation. By the midpoint of the war, other than search & rescue, anything a battleship’s planes could do, an aircraft carrier’s planes could do better.

(To the left is the early basic concept model for the Montana class battleships in 1941. It was then envisioned to have two catapults and a hangar for four SOC Seagulls. To the right is the final 1944 builder’s reference model. The aviation fit had been trimmed to one catapult and two SC-1 Seahawks. The entire Montana class was cancelled.)

The biggest factor ending surface combatant aviation after WWII was increasing use of helicopters.

(U-858 surrendering to a US Navy subchaser and US Coast Guard HNS-1 Hoverfly one day after Germany’s overall surrender.)

During the later part of WWII, the US Coast Guard made enthusiastic use of helicopters, limited only by the small numbers available. Immediately after WWII, the US Navy saw tremendous potential in the ASW, lifesaving, and gunfire spotting roles; which by the end of WWII were basically the only missions remaining for catapult seaplanes. The US Navy began the shift towards helicopters for surface combatants, which was the beginning of the end for catapult seaplanes.

Helicopters offered every advantage over seaplanes; the most important being that no ship maneuvers were required for launch or recovery. Additionally the topweight of catapults could be removed and the dangerous 5″ blanks eliminated.

Regardless of the future of helicopters, another factor in 1945 was cost. Congress massively slashed the defense budget after Japan’s surrender. The US Navy estimated in 1946 that just one flight-hour of one SC-1 Seahawk cost $203 ($2,759 in 2017 money). At the time, this was half a month’s wage costs for an average seaman. There was also the expense of the support gear. It was mandatory to perform maintenance on the Type P Mk6 catapult after four uses during WWII. In peacetime, most battleship captains dictated upkeep after each launch.

The planes themselves were subject to regular damage. Naturally an airplane’s wings are designed to catch the air. On a battleship moving 25 kts into a 15mph headwind, this created airflow onto the wings roughly the same as a car on the freeway. An elaborate system of tiedowns was needed for planes parked on a catapult, even more so if they had their wings unfolded. Even with all that, a storm could easily destroy them, like this Kingfisher aboard USS Missouri.

During the 1946-1949 drawdown of the US Navy, every effort was made to reduce the operating cost of WWII ships still in service. Some vessels which retained catapults did not always go to sea with planes after WWII.

(The stern of USS Washington (BB-56) during a post-WWII visit to the US Naval Academy at Annapolis, MD in 1946. The catapults are still onboard but the planes were already gone.)

After Japan’s September 1945 surrender all remaining SOC Seagulls, and the hated SO3C Seamews, were discarded. This was completed by March 1946.

(USS San Francisco (CA-38) a month after the end of WWII, making a visit to newly-independent South Korea. A SOC Seagull is still aboard. With Japan’s surrender, efforts to replace remaining SOCs ended, as their host ships would themselves soon decommission. This is therefore a somewhat rare photo of a biplane in post-WWII American use.)

The remainder of the WWII-budget SC-1 Seahawk order was immediately terminated by Congress, with the final 439 planes being cancelled. Those already delivered remained in use.

(One of the last Seahawks built ended up aboard the cruiser USS Manchester (CL-83), here being hoisted aboard in 1948. With WWII over, a bit of flair returned to seaplane markings, such as the ship’s name around the national emblem. USS Manchester had her catapults deleted a few months later.)

For OS2U Kingfishers in use on V-J Day, those near their next scheduled maintenance were discarded. During the last few months of 1945, and the start of 1946, any Kingfisher that had mechanical problems was discarded immediately.

(Disposal of Kingfishers started even before Japan surrendered. “War-weary” planes, like this one at Ulithi Atoll, were stripped of anything useful then dumped into the Pacific.)

By the summer of 1945, aircraft carriers were so common in the US Navy that it was rare for any task force of any type to lack at least an escort carrier. Even before WWII ended, there was declining demand for catapult seaplanes. On ships with two, one catapult was sometimes left empty.

(USS Little Rock (CL-92) in heavy seas near the end of WWII. The starboard catapult has a utility boat stored on a dummy car. After WWII, similar but built-for-the-purpose boat rails completely replaced some catapults.)

USS Fargo (CL-106) and USS Huntington (CL-107) were the first American cruisers commissioned after WWII. They were built during WWII’s final months but not commissioned until December 1945 and February 1946. Eleven were cancelled after Japan’s surrender and these two were completed more to cushion the financial blow to New York Shipbuilding, rather than any naval need. They were designed with two Type P Mk6 catapults and a hangar for four SC-1 Seahawks.

During construction the starboard catapult was replaced by a smallboat rail (as seen below) and half the hangar was converted into sleeping quarters.

The remaining catapult was later removed to free up space for helicopters. The crane was retained. These two cruisers had short careers (USS Huntington only 35 months), and were expensive vessels that gave little use.

The final American class to actually carry catapults at commissioning were the three Des Moines class cruisers, which were started during WWII but not commissioned until 1948-1949. They were designed for two Type P Mk6 catapults and four SC-1 Seahawk planes. Almost immediately, the starboard catapults were replaced by a boat rail.

Later, the port catapult and all seaplane facilities were eliminated entirely, as was the boat rail, replaced by a larger smallboat rack. The Des Moines class operated helicopters only during the Korean War.

The two Worcester class cruisers, USS Worcester (CL-144) and USS Roanoke (CL-145) were the final American warships to even have catapults considered in their design. They commissioned in 1948 and 1949. During WWII in their early concept work, it was planned to fit two Type P Mk6 catapults and a hangar for four SC-1 Seahawks.

(Late-WWII concept model of the Worcester class, showing two catapults.)

During post-WWII construction, the seaplane facilities were eliminated and redesigned into a smallboat hangar (served by the seaplane crane) and an open space for helicopters.

(USS Worcester as built, with a helipad and no catapults.) (photo by Marius Bar)

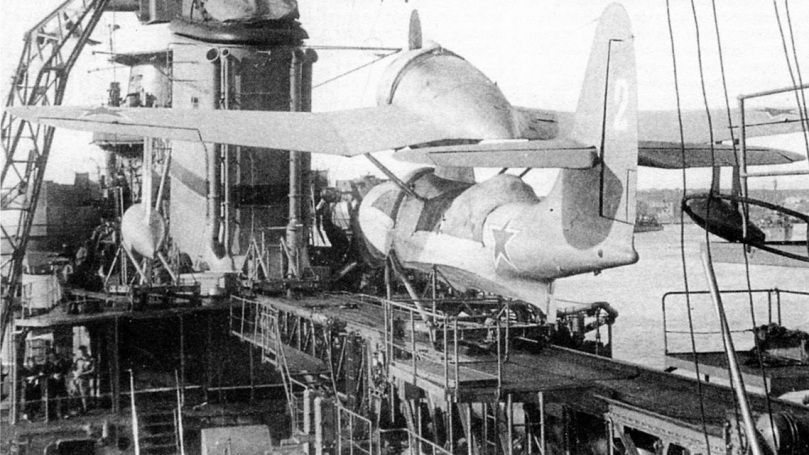

This trend was followed in the few navies with capital ships after WWII. France’s battleship Richelieu had her catapults removed even before WWII ended and her sister Jean Bart never had them installed. The Soviet navy removed it’s remaining catapults in 1948.

(The last Soviet catapult seaplane type was the Beriev Be-4.)

The Royal Navy’s final battleship, HMS Vanguard, never had catapults at all. As a cost-cutting measure HMS Anson, the last of the war-built King George V class, did not embark seaplanes inbetween the end of WWII and the battleship’s decommissioning in 1949.

Throughout 1946, it was common for US Navy cruisers to go to sea without their aviation detachment, to reduce manning costs.

(USS Oregon City (CA-122) with empty catapults in 1946. This photo gives a rare view of the toothed gear underneath the Type P Mk6 which the electric motor turned the catapult on. The officers are wearing the WWII “medium grays” uniform, which was obsoleted in 1949.)

During the final week of June 1946, the US Navy phased out the last OS2U Kingfishers. These planes enjoyed a phenomenally successful 6-year run, including the entirety of WWII, but were now at the end of their airframe lives. Their withdrawal allowed full concentration of dwindling catapult plane funds towards the SC-1 Seahawks. The official retirement date of the Kingfisher from American service was 1 July 1946.

In early 1947, the US Navy studied the feasibility of removing all combat equipment off remaining SC-1 Seahawks, as they were now being tasked completely with rescue missions only. One plane was modified with the guns, bomb pylons, and pilot armor stripped off, lightening the Seahawk by 471 lbs and increasing speed and range. This project’s budget was cancelled shortly thereafter.

(Newspaper clipping from 1947.)

One SC-1 Seahawk with the wheeled undercarriage option was used by NACA, a forerunner of NASA, for research from 1945 to 1949.

(The NACA airfield is today NASA’s Langley Research Center.)

After a reduced training schedule in 1946, the catapult training ship USS Absecon (AVP-23) ceased seaplane operations in March 1947. This ship had an interesting post-WWII career. During 1949 all WWII seaplane gear was removed and the vessel transferred to the Coast Guard as the cutter USCGC Absecon (WHEC-374). On 15 June 1972, the Coast Guard donated the ship to the South Vietnamese navy as HQVN Pham Ngu Lao. When North Vietnam overran Saigon in 1975, the old cutter was unable to escape and was captured intact. Later rearmed with Soviet-made missiles, the ship served the Vietnamese navy to the turn of the millennium.

(HQVN Pham Ngu Lao, the old USS Abscenon, during the Vietnam War.) (photo via Navsource website)

As a cost-cutting measure, direct assignment of seaplanes to ships with catapults ended in 1947. The remaining Seahawks were organized into a “library” system, where a battleship or cruiser would “borrow” one when needed for a mission then return it afterwards.

Regardless of money, the number of hulls big enough to carry catapults was dwindling rapidly. Many of the WWII cruisers and almost all the battleships were going away.

(USS New York (BB-34) with Seahawks aboard in February 1946, five months after WWII. The old battleship was expended as a nuclear target at Bikini several months later.)

While catapults were being removed, the cranes were left aboard many ships. Capable of deadlifting several tons off a pier, they were useful for many tasks.

(USS Baltimore (CA-68) in 1952 with the cranes left on after the catapults were removed.)

By Thanksgiving Day 1948, there were only ten active-duty warships in the US Navy still carrying catapult seaplanes. As many SC-1 Seahawks still had good flight-hours remaining on their airframe fatigue lives, some were vacuum-sealed for preservation in storage. This was all for nothing as after the Korean War ended in 1953, the still-sealed SC-1s were scrapped.

In May 1949, squadron VO-2 at Norfolk, VA announced plans to convert to helicopters. At the time it was the last active-duty catapult plane squadron in the US Navy, so this was the end of the road for aircraft on battleships and cruisers.

June 1949 was the final month of SC-1 Seahawk operations. By this time, all had been off warships for over a month already. During the Independence Day celebrations on 4 July 1949, the US Navy officially commemorated the end of catapult seaplane aviation, a technology which had started in the 1920s. Sadly no thought was given to preserving a SC-1, and all Seahawks were scrapped.

In 1949, the US Atlantic Fleet issued an order for the removal of the starboard catapult on all inactive battleships. In 1951, the US Navy supply system stopped supporting some parts, including the dummy cars. In 1954, a general directive was issued that all mothballed vessels with catapults have them removed. This was not carried out with any urgency, for example the mothballed cruiser USS Oklahoma City (CL-91) did not lose her catapults until 1957. The decommissioned USS Alabama (BB-60) had both catapults removed in the late 1950s however their mounting seats were left unaltered, and one catapult was retained in storage with the ship.

(The mothballed USS Alabama being moved by tugs at the Bremerton, WA reserve anchorage during the Cold War. One catapult is inside the temporary wooden shed, along with some of the ship’s radar antennas. The catapult turntables are visible.)

When USS Alabama became a museum ship, it was reinstalled and today in 2017 is the only authentic, unaltered Type P Mk6 catapult remaining.

The removed WWII catapults were scrapped. One was used ashore by Naval Sea Systems Command during the Cold War as a means of non-destructively projecting objects at high velocity.

The Iowa class – end of seaplanes aboard battleships

The US Navy retained in use the four operational Iowa class battleships.

USS Wisconsin (BB-64) had a reduced-manning aviation detachment in 1946, and ceased catapult training flights in February 1947.

(USS Wisconsin firing a 16″ broadside during a 1947 gunnery drill near the Panama Canal Zone. The catapults were still aboard but unused by then.)

In 1949, USS Wisconsin‘s starboard catapult was removed. In early 1951, during a scheduled upkeep period, the port one was removed as well, and all aviation-related items other than the crane were removed.

(USS Wisconsin drydocked at Norfolk, VA in 1951. The remaining catapult, visible here, was removed during this drydocking.)

During the Korean War, the freed-up space on USS Wisconsin‘s stern was used to fly helicopters. This continued until the ship’s first decommissioning.

(USS Wisconsin with a HO3S-1 Dragonfly during winter operations in the Korean War.)

(The area where seaplanes once sat could experience rough weather. During the NATO exercise “Mainbrace-52” in 1952, this staff car was carried as deck cargo and crushed by a huge wave. For the exercise USS Wisconsin was in a joint squadron with HMS Vanguard. It was the final time American and British battleships sailed together.)

(USS Wisconsin on a 1956 training cruise, now with a completely empty aft deck.)

(USS Wisconsin during the NATO exercise “Strikeback-57” in 1957. The aft deck is being used for boats and helicopters, with the seaplane crane in it’s fully down position.)

USS Missouri (BB-63) continued operating seaplanes the longest of the four Iowa class ships. Both catapults were retained, and regular training flights continued until February 1949.

(Uniquely, for a while in 1948, USS Missouri flew both catapult seaplanes from her stern and helicopters from a makeshift helipad atop the “A” turret.)

(During a May-June 1949 upkeep period, both of USS Missouri’s catapults were removed together. This photo was taken a week or two after they were pulled off.)

(USS Missouri during the 1951 Inchon amphibious assault which turned the Korean War in America’s favor. The aft deck, now stripped of catapults, is cluttered with invasion gear.)

USS New Jersey (BB-62) ceased catapult training during the summer of 1946. Both catapults were left aboard but no longer manned nor maintained. In October 1950, both were quickly removed to make the ship ready for Korean War operations.

(USS New Jersey during the Korean War.) (photo from Haze Gray website)

(A HO3S-1 Dragonfly lands on USS New Jersey during the 1950s. With the catapults gone, this area was used for helicopter operations. The only real change was a small square of non-skid laid over the teak deck.)

USS Iowa (BB-61) continued sporadic seaplane operations after WWII until September 1948.

(USS Iowa in July 1947, still with catapults and SC-1 Seahawks onboard.)

The ship still had Seahawks onboard after the last training flights concluded. In March 1949, it was ordered to ferry these planes to an ashore base. Perhaps nobody realized it at the time, but this would end up being the final battleship catapult flights in history.

(This was the Seahawk off USS Iowa which made the final catapult launch in 1949. No special ceremony was held; perhaps it was not realized aboard that this was the last seaplane still aboard any battleship.)

In August 1951, both of USS Iowa‘s catapults were removed at the same time. The space was used for helicopter operations.

(H-13 Sioux aboard USS Iowa during 1951.)

(USS Iowa’s stern in 1952. The catapults are gone and the aft deck is being used to move boats and cars to South Korea.)

(USS Iowa during a 1957 training cruise. Aircraft is a HUP-1 Retriever.)

(part 1 of a 2-part series)

Reblogged this on Brittius.

LikeLike

Very interesting collection of information. The seaplanes proved themselves to be so versatile during the war, yet so many still know very little about them. Great job!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good article as usual, just two things.

Talking in a pre WW2 context, a “Frigate” is anarchonistic, Frigate wasn’t used as a warship class before 1942 by the RN and would have symbolized a age of sail warship before that.

It was most certainly a destroyer in the plane guard role.

Re Kriegsmarine and catapult aviation, the Kriegsmarine had Landing Sails, which was similar to the USN landing mat but larger, which were considered too elaborate and in fact were rejected in favor of the normal method. Maybe the twin float arrangements of most german onboard seaplanes made them more stable in the water compared to the centerline float of US floatplanes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] The San Diego Air and Space Museum have several better quality images on their Flickr site and you can find a good photograph of USS Pennsylvania with two planes mounted aft on this well researched page about the short history of catapult aviation. […]

LikeLike

Dad was aboard the USS Missouri when they flew off the last plane. By the time he left the ship, the cats were gone.He was “forced” off the ship to go to radio school at Great Lakes in 1950 where he got held back as instructor till 1953. He never got a chance to go back aboard even though he tried.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] and by the mid-1920s, spotting was perceived as so important that U.S. battleships added seaplane catapults to their aft turrets to ensure aircraft were available. To further increase the availability of aircraft and relieve […]

LikeLike

[…] by the mid-1920s, spotting was perceived as so important that U.S. battleships added seaplane catapults to their aft turretsto ensure aircraft were available. To further increase the availability of aircraft and relieve […]

LikeLike

Outstanding post! On a picture above, with towers the catapults rest on, identified as Omaha-class cruisers, that’s a New Orleans-class heavy cruiser in the picture, with hangar to the left, then to right the twin stacks with searchlight platform in between. Not to take away from the fine post you made, really interesting.

LikeLike

Naval Aviation News from June 1948 features a two page report on SC-1s in Shanghai, China from USS Duluth, CL-87, circa late 1947, early 1948… https://books.google.com/books?id=YSBgbojkC6sC&pg=RA5-PA8&lpg=RA5-PA8&dq=sc-1+seahawk+china+USS+duluth&source=bl&ots=eFFkRdbIpD&sig=ACfU3U0p_JInxCP_8Tr6Di0OrjGsTVE6lg&hl=en&sa=X&

ved=2ahUKEwjO5LulxpblAhW5ITQIHc5iBdsQ6AEwBHoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=sc-1%20seahawk%20china%20USS%20duluth&f=false

LikeLike

The USS Worcester was commissioned with 2 catapults in 1948. They were both removed during a 1949 maintenance period. http://ussworcester.com/coppermine/displayimage.php?album=2&pid=33#top_display_media

LikeLike