HMS Mendip, a British WWII destroyer, served in four navies after the war and saw combat in two wars, including being captured on the high seas, certainly a rarity in the modern era.

(HMS Mendip serving in the Royal Navy during WWII.)

(The former HMS Mendip in Israeli service as INS Haifa after her capture at sea from the Egyptians.)

The Hunt class destroyers were designed just before the start of WWII, but most were built during the war. HMS Mendip was the 13th member of the class, being launched by Swan Hunter shipyard in April 1940 and commissioning on 12 October 1940. HMS Mendip served as a convoy escort for most of WWII, but also participated in operation “Husky”, the invasion of Sicily; and operation “Overlord”, the colossal invasion of Normandy.

Basic description

The Hunt class displaced 1,360 tons and measured 278’10″x28’10″x10’9″. They were powered by two Admiralty boilers, with two Parsons geared steam turbines turning two 3-bladed propellers. The top speed was 26 kts sustained and a burst speed of 27 ½ kts. During WWII, the full complement was 146 officers and enlisted sailors.

The main armament was four Mk.XVI 4″ guns, paired in two Mk.XIX powered turrets. This gun fired a 35 lbs shell. In theory the maximum range was around 11 NM however accuracy at that range would be abysmal, and 6 – 7 NM was more realistic. This gun had a secondary anti-aircraft role, and for AA use a fuze-setting device was installed.

(The forward twin 4″ gun mount of INS Haifa, today preserved ashore.)

The secondary gun armament was a Mk.IV twin 40mm AA gun with a range of 7,000 yards and a ceiling of 23,000′, and finally two Mk.III 20mm close-in AA guns. A manually-operated 2-Pounder gun was originally carried on the bow but removed at the end of WWII.

For use against submarines, there were two DCT depth charge projectors and a traditional stern depth charge rack, with a combined total of 40 depth charges. HMS Mendip was fitted with a Type 123 sonar, a WWII British design of limited viability by the 1950s.

The main combat sensor was a Type 285 gunnery radar above the bridge. The ranging accuracy of this radar was ±100 yards and the bearing error was ±2° which made it questionable for use in ‘blind’ gun duels. During the early part of WWII it was better than nothing but by the mid-1950s this was a fairly dated system. The Type 285 was generally replaced by newer radars aboard warships the Royal Navy retained postwar, but, as the first subgroup of the Hunt class was unwanted this was never done aboard HMS Mendip so the Type 285 was still in use when the ship was sold to Egypt.

The search radar was a Type 291 at the top of the main mast. This WWII radar could detect a destroyer at 6 – 9 NM, and an average-sized airplane at 15 NM. Finally there was a Type 268 navigation radar.

HMS Mendip after WWII

In July 1945, with the European part of WWII over, HMS Mendip was used in operation “Deadlight”, the mass scuttling of unwanted ex-German u-boats.

HMS Mendip belonged to the first subgroup of the Hunt class, which exhibited problems during WWII. The hull itself was unstable in rough weather, and the armament was not sufficient. The Royal Navy was keen to get rid of the first subgroup after Germany’s surrender in May 1945, and of those that survived WWII, all had decommissioned by late 1946.

To China

On 18 May 1948, ownership of the decommissioned HMS Mendip was passed to the nationalist government of China, fighting a civil war against Mao’s communists. The transfer, a no-cost 5-year loan, was made effective the following day. The nationalists renamed the destroyer ROCS Lin Fu.

ROCS Lin Fu accomplished very little in Chinese service as the nationalist position on the Chinese mainland was collapsing. On 25 February 1949, the light cruiser ROCS Chun King (formerly the WWII Royal Navy’s HMS Aurora) defected to Mao’s communists. This followed a string of reports from the nationalist fleet which said that American- and Australian-supplied WWII warships had been “abandoned and seized”, or “captured in port”, by Mao’s troops. The British (correctly) estimated that some or many of these instances were actually the crews defecting, and saw no need to give the communists yet another warship.

Several days after the cruiser’s defection, the British Home Office transferred the destroyer’s loan title back to the Royal Navy, which immediately voided the transfer and repossessed the vessel. Part of the crew of HMS Consort, which was being repaired in Singapore after damage from Chinese communist artillery on the Yangtze River, was sent to China to retrieve HMS Mendip.

To Egypt

In the summer of 1949, the Royal Navy had zero interest in keeping the repossessed HMS Mendip. For a few months the WWII destroyer served in the Asia squadron, but this was unattractive due to the spare parts issue (HMS Mendip was the only Hunt class in the region) and the general obsolescence of the warship. In late summer, HMS Mendip was ordered back to Europe. Along the way, a buyer was found in the Egyptian navy, which was in the midst of a somewhat haphazard buying spree after the Israeli war of independence the previous year. The sale price was very attractive and not much more than the destroyer’s scrap value.

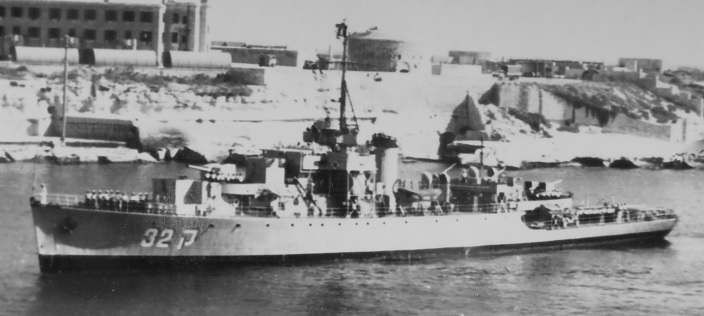

(ENS Ibrahim el-Awal in Egyptian navy service.)

In naval terms, warship sales are either “cold” (a vessel is pulled out of storage) or “hot” (the ship is already in service with the selling country). The HMS Mendip sale was as “hot” as it gets; when the destroyer passed through the Suez Canal the British crew simply went ashore and were immediately replaced by Egyptians, without ever even shutting down the ship. The sale was obviously “as-is” in the most literal sense of the word; as everything on board (including small arms, rations, spare parts, fuel, etc) was included in the price, but nothing more.

(Letterhead of official ship’s stationary aboard ENS Ibrahim el-Awal.)

On 15 November 1949, HMS Mendip officially transferred to Egypt, being renamed ENS Mohammed Ali el-Kebir. In 1951, the name was changed to ENS Ibrahim el-Awal.

Start of the Suez conflict

The 1956 Suez conflict was a poorly-planned three-way operation between France, the UK, and Israel; opposing Egypt. The two European powers wished to prevent Egypt from nationalizing the Suez Canal, and along with that, destroy as much of Egypt’s military as possible. Israel wanted to stop Egyptian coastal guns in the Sinai peninsula from shelling Israel-bound shipping and more generally, to diminish Egypt’s warfighting ability in the Sinai.

The plan was for Israel to make a limited attack on Egyptian troops in the Sinai. Then, the European powers would “safeguard the Suez Canal” by demanding both sides cease fire, which would be impossible for Egypt, under invasion, to do. This would be the pretext for the Anglo-French invasion and seizure of the canal.

The conflict started as planned on 29 October 1956 with the Israeli ground assault. A French navy planning group was in Haifa, Israel to coordinate with the Israeli navy. The British and French had instructed the Israeli navy not to participate in any way, as the Egyptian naval threat was deemed minor and the presence of Israeli warships in the area would just add confusion for the Anglo-French fleet off the canal’s northern mouth.

On the morning of 30 October, ENS Ibrahim el-Awal departed Alexandria, Egypt on a mission to sneak up the Mediterranean coast and bombard the Israeli navy’s home port of Haifa. Quite amazingly the destroyer managed to slip unnoticed past the Franco-British fleet approaching Port Said for the upcoming assault, and also the Israeli air force which was operating over the northern Sinai.

The Israeli task force

Held back per the agreement with France and Britain, Israel’s task force in the area consisted of three ships. The Israeli task force and ENS Ibrahim el-Awal must have nearly passed one another in opposite directions late in the night of 30 October.

The Israeli ships were INS Yaffo, a WWII Z-class British destroyer (formerly HMS Zodiac), her WWII sister ship INS Eilat (formerly HMS Zealous), and a WWII Canadian River class frigate, INS Miznak (formerly HMCS Hallowell).

(INS Yaffo, formerly HMS Zodiac during WWII.)

(INS Eilat, formerly HMS Zealous during WWII. This destroyer later had the misfortune of being the first ship sunk in combat by a ship-to-ship guided missile.)

(INS Miznak, formerly HMCS Hallowell during WWII.)

Of these three WWII-vintage warships, the two Z-class were the most capable combatants in the Israeli fleet at the time. INS Miznak was rated as a “slow frigate” by the Israelis and considered of lesser ability.

There was also a small flotilla of patrol boats and motor launches screening the southern approaches to Haifa. This unit missed ENS Ibrahim el-Awal, probably for the best, as even together they were not suited for fighting a destroyer on the open seas.

The bombardment of Haifa

At 03:30 on 31 October 1956, ENS Ibrahim el-Awal arrived off Haifa and began it’s bombardment of the port. According to Israel, the bombardment only lasted a few minutes and was haphazard, not causing much damage.

Unbeknownst to the Egyptian captain, the French destroyer Kersaint was moored at Haifa naval base. For the French naval liaison team ashore, the unexpected appearance of the Egyptian destroyer was a political problem, as per the plan for the war, the Europeans were pretending to be neutral until daybreak that day, still several hours away.

(The French destroyer Kersaint.) (photo via DCN Shipyards)

Kersaint was a very modern and new (in fact, on her maiden deployment) Cold War-era destroyer which outclassed the WWII-era Egyptian ship in every way. Kersaint was fitted with three twin 5″ guns and a half-dozen 57mm weapons, and had the newest French radars in service.

The captain of Kersaint was apparently uninterested in political niceties and as Egyptian shells started landing on the pier, he ordered his ship to return fire. Soon 5″ rounds began landing near ENS Ibrahim el-Awal which quickly concluded it’s bombardment.

The Egyptian navy’s plan for the attack was for ENS Ibrahim el-Awal to not return to Egypt after the bombardment. Instead, the destroyer was supposed to arc northwest then back northeast, to arrive at Beirut, Lebanon. Lebanon was neutral and per the Geneva Conventions, in theory ENS Ibrahim el-Awal would be interred; however the Lebanese public was avidly anti-Israel and the Egyptians were confident the ship and crew would be taken care of and free to go as soon as the tactical situation allowed. The Egyptian government doubted that Israel would attack a ship in neutral Lebanon, and were nearly certain the Europeans wouldn’t.

The pursuit

Just before 05:00, with the sun coming up, an Israeli air force C-47 Skytrain (known to the Israelis by it’s WWII RAF name, Dakota) began a search for the offending ship. The Israelis used these WWII-veteran transports for a number of roles, visual reconnaissance being one of them. Almost immediately the C-47 located ENS Ibrahim el-Awal, now steaming northwest away from Haifa. The destroyer’s location was radioed to the Israeli task force sailing far to the south.

(A WWII-vintage C-47 of the 1950s Israeli military assigned to maritime reconnaissance.)

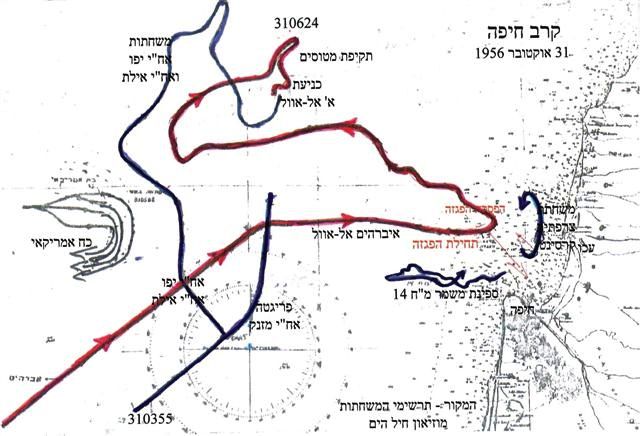

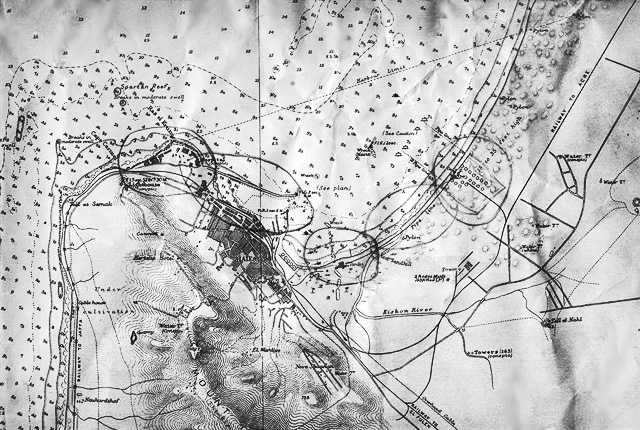

(An Israeli chart of the events, showing ENS Ibrahim el-Awal in red, and the three-ship Israeli flotilla which split up. The smaller blue traces are patrol units near Haifa, and the grey traces are the neutral American warships.)

The Egyptians counter-detected the slow, lumbering Dakota (which stayed out of AA gun range) and knew they were being tracked. The captain of ENS Ibrahim el-Awal radioed the Egyptian navy GHQ in Alexandria and requested instructions. The reply was to stick to the original plan, as the Syrian air force had warplanes en route to provide air cover. (This was entirely untrue.)

The Israeli task group split up. INS Eilat and INS Yaffo broke northwest at maximum speed to cut off the destroyer (which had yet to be positively identified), meanwhile INS Miznak continued on the original course and speed in case the enemy vessel doubled back southeast.

At 05:07, the radar of INS Eilat acquired a large surface contact 17 NM north, moving at 25 kts. Both Israeli ships sped up to intercept and engage the ship, which they were sure was an Egyptian destroyer.

At 05:17, radarmen on both Israeli warships acquired four surface contacts approaching them from the west, seemingly on an intercept course. At this point the Israeli task force commander, Cpt. Shmuel Yanai, feared that the shelling of Haifa was a diversion intended to lure his ships into a pincer trap. Risking certain destruction if he was wrong, he maintained course until the four vessels to the west were in visual range. He then identified his force as Israeli via morse code on a searchlight, and nervously waited for what would happen next. A moment later the ships to the west replied via searchlight that they were neutral American warships of the US Navy 6th Fleet. Apparently, one of the American warships also later announced it’s nationality on open-frequency radio. When the lone ship to the north did not reply, the Israelis knew for sure it was Egyptian. The American captains probably figured out what was about to happen and turned 180° to avoid being caught in the crossfire.

The battle

At 05:28, the Israeli ships were about 6 NM away from ENS Ibrahim el-Awal which was now positively identified. The fire control teams, using WWII British equipment, began calculating target solutions as the 4 ½” guns of the Israeli vessels were now in range.

At 05:32, both Israeli warships opened fire, both about 9,000 yards range but on opposite beams of ENS Ibrahim el-Awal. The Israeli captains poured on the shells, as they felt time was of the essence due to the expected arrival of Egyptian warplanes at any moment. At 05:34, ENS Ibrahim el-Awal began to return fire, however it was not at a consistent rate and extremely inaccurate. Faced with opponents on multiple bearings, it’s possible the Egyptian fire control team released each mount to local visual control. From 05:35 onwards, the Israeli ships recorded what they believed to be hits on the Egyptian destroyer.

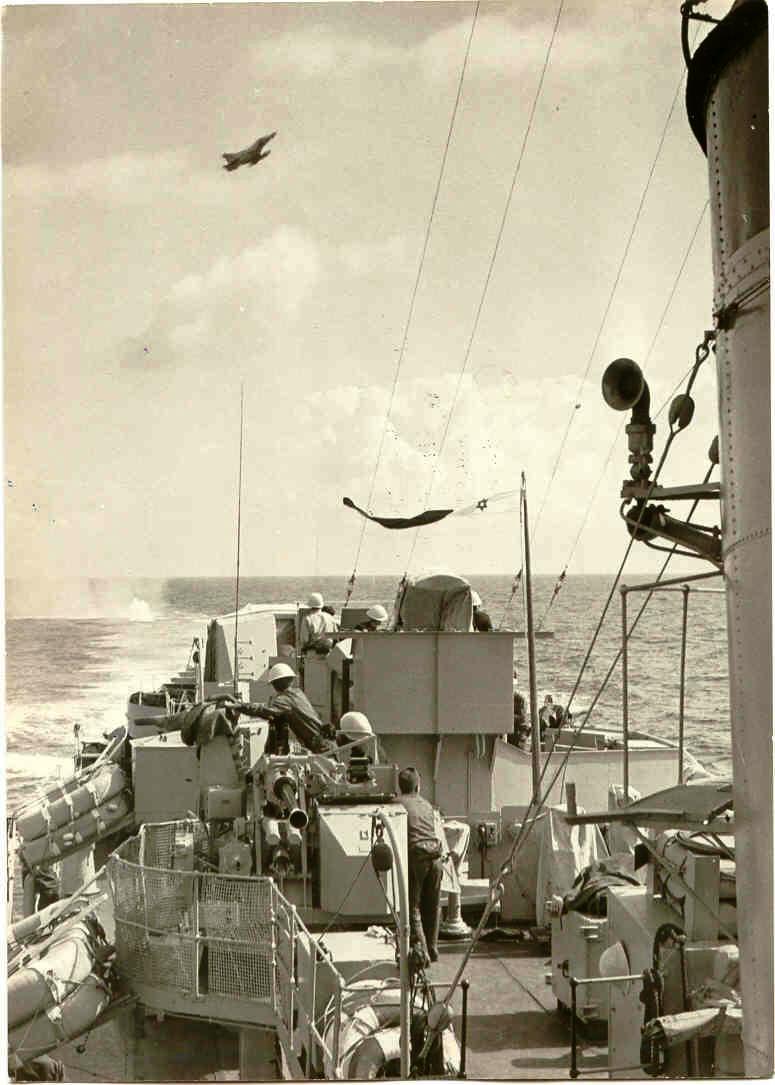

(ENS Ibrahim el-Awal during the battle.)

At 06:00, lookouts on the Israeli ships reported that ENS Ibrahim el-Awal had slowed to 17 kts. The Egyptian vessel was now heading almost due north. At this point the counterfire coming from the Egyptian ship was very slow and sporadic, and still missing by a wide margin.

At 06:37, a pair of Israeli air force Ouragan jets arrived and attacked the Egyptian destroyer with unguided air-to-ground rockets. With their rockets expended, the Israeli Ouragans then strafed ENS Ibrahim el-Awal with their Hispano 20mm guns before departing.

(A French-made Ouragan attack jet of the Israeli air force.)

The capture at sea

Around 06:50, the Egyptian ship lost steerageway (ability to maneuver). At 07:00, lookouts on INS Eilat reported that it appeared that the situation on the Egyptian ship was out of control, and some crewmen were jumping overboard. The captain of INS Eilat judged the situation in hand enough to momentarily break off his ship’s attack, and lower two lifeboats to rescue Egyptian sailors. One of the lifeboats got stuck on it’s derrick. At 07:03, ENS Ibrahim el-Awal went DIW (dead in the water; motionless) and ceased fire.

(The damaged ENS Ibrahim el-Awal.)

At 07:05, astonished lookouts on INS Eilat reported that ENS Ibrahim el-Awal had hoisted a white flag. It was almost unbelievable that in the year 1956 a man-o-war would “strike the colors” as in the age of sail. Soon lookouts on INS Yaffo confirmed seeing the same thing. Both Israeli destroyers now lowered every available smallcraft into the water, full of armed sailors instructed to board and secure the surrendering Egyptian warship. They were ordered to first secure the crew then secure any available intelligence before the destroyer sank. In case it was an Egyptian trap, INS Eilat lined up to fire a Mk.IX unguided torpedo. This straight-running WWII-vintage British weapon had been judged unsuitable for use against the rapidly-maneuvering Egyptian ship during the battle, but would now be the ultimate insurance policy.

(Israeli personnel aboard the Egyptian destroyer, it’s now-silent forward turret trained to starboard.)

(The surrendered destroyer, DIW.)

Cpt. Josef John (the turret commander of the forward gun aboard INS Eilat) led the boarding party. He spoke Hebrew, Arabic, and English; so it was reasoned he was best suited for the task. Aboard ENS Ibrahim el-Awal, he was greeted by the Egyptian captain, who confirmed that he was indeed surrendering at sea. The Egyptian captain told him he had two KIA and eight more wounded, not counting men in the water. He also said that he prohibited his sailors from carrying sidearms at sea, which was a relief to the Israelis.

(The stern of ENS Ibrahim el-Awal after the destroyer had been boarded. This shows a WWII-vintage Mk.VII depth charge on the DCT projector, with two reloads in the rack next to it. It was quite fortunate for the Egyptians that the strafing Israeli jets did not set off any of the depth charges.)

(Israeli sailors assemble some of ENS Ibrahim el-Awal’s crew on deck by the aft main gun mount.)

After assembling the Egyptian sailors on deck and beginning treatment of the wounded, the Israelis began inspecting ENS Ibrahim el-Awal and found that the damage they had dealt out was not nearly as severe as they had thought. The boarding party radioed to Col. Menachem Cohen, captain of INS Eilat, that not only were they going to secure intelligence; they might actually do the unthinkable and take the Egyptian destroyer intact as a war prize.

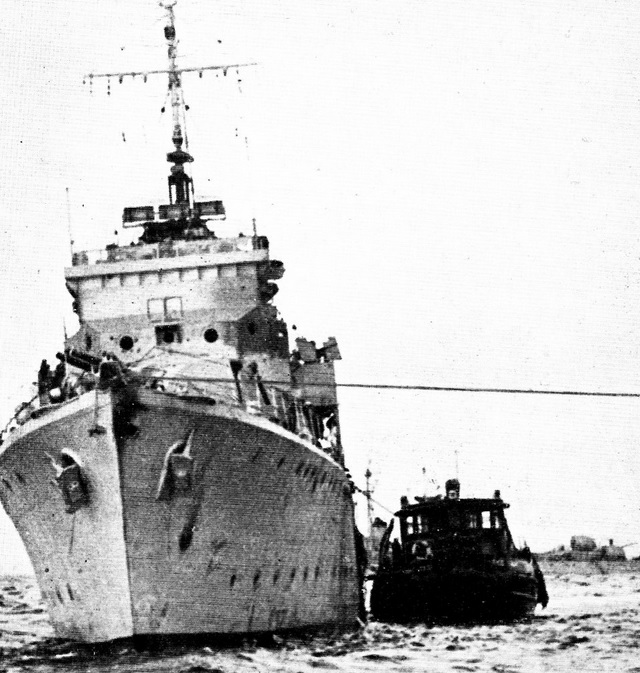

INS Eilat came alongside and took the crippled Egyptian ship in tow. INS Eilat was obviously not designed as a tug and for 4 hours, the Israeli destroyer began to slowly pull ENS Ibrahim el-Awal towards Haifa. This was quite difficult as the dead Egyptian ship’s rudder was stuck to hard starboard. At 13:45, two civilian tugboats from Haifa arrived and took over.

(A tow line from INS Eilat is attached to the captured destroyer.)

(The captured ENS Ibrahim el-Awal being taken on by a civilian tugboat from Haifa.)

(The two tugs had to work together to accomplish the tow of the crippled destroyer. The shell hit to the extreme upper port side bow is visible here.)

Aftermath of the battle

Late in the afternoon of 31 October 1956, the two tugs, the captured Egyptian ship, and INS Eilat arrived at Haifa. Perhaps nobody was more flabbergasted the the French liaison team who watched, eleven years into the atomic age, a high seas prize ship being towed to port as in the age of sail.

(Under tow, the war prize approaches the Israeli coast.)

(Israeli servicemen ashore watch the amazing spectacle. The rifle is a WWII German 98k, which the Israeli Defense Forces used extensively at the time.)

(The Israelis did the ancient naval custom of raising the victor’s flag over the vanquished’s aboard a prize captured at sea.)

(The naval ensign of Israel, and that of Egypt as it appeared at that time.)

A team of Israeli MPs met the ship and took custody of the Egyptian POWs. They were duly registered with the Red Cross and sent back to Egypt after the end of the Suez crisis.

(An Israeli MP unit arrives at the pier to take custody of the Egyptian crew.)

(Israeli MPs make a head count of the Egyptian POWs for Red Cross documentation.)

The French navy received permission to inspect and document the war prize. Amazingly, only five shell holes of 4½” size were found; meanwhile the two Israeli ships logged 436 rounds expended between the two of them…only a 1.2% hit rate. One 4½” shell had hit the extreme bow and was a ‘through & through’ (exiting the other side of the hull); despite being the most visible damage, it struck an empty chain locker and was irrelevant.

(Close-up of the hit to the bow.)

Another 4½” round hit underneath the aft gun mount. This was the most destructive as the shell shattered inside the ship with one piece destroying one of the boilers, and another damaging some machinery and destroying one of the turbogenerators which fed the electrical system. The initial impact itself damaged the magazine hoist for the aft gun. A third 4½” round hit underneath the forward main gun turret, damaging it’s operating mechanism. The remaining other two 4½” hits were to berthing areas.

Of the 32 air-to-surface rockets fired by the Ouragans, only one hit was found by the French (the Israeli air force disputed this). The armor-piercing warhead penetrated the weather deck, went through the wardroom, and exploded in a machinery space, further crippling ENS Ibrahim el-Awal. The number of 20mm strafing hits was not counted but “many”, perhaps this was demoralizing to the Egyptians more than anything as the bullet holes topside made the destroyer’s condition look worse than it was.

The French reported no 5″ hits so apparently all of Kersaint‘s counterfire missed.

The captain of ENS Ibrahim el-Awal, Maj. Rushdie Tamsyn, gave a limited debrief to the Israelis. He said that the targets he was assigned to attack were vague; this was supported by Egyptian intelligence maps captured aboard the ship which were woefully inept, showing industrial / military sites in Haifa in the wrong locations or missing. He stated that he had fired 160 4″ rounds at the city over a 45-minute period. This was more shells and a far longer timeframe than the Israelis stated. Tamsyn stated he was given no warning of any French warship in Haifa and thought that the counterfire of Kersaint was Israeli army heavy artillery ashore.

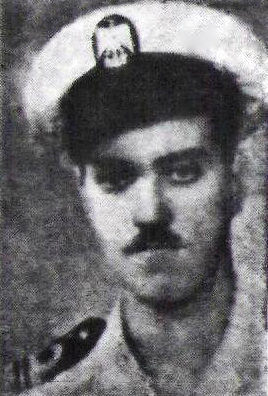

(Rushdie Tamsyn, final captain of ENS Ibrahim el-Awal.) (Egyptian navy photo)

(An Egyptian navy chart of Haifa, captured aboard the destroyer.)

Maj. Tamsyn said that during the maneuver towards Beirut, one of the propellers (he may have meant engines or boilers) began having mechanical problems. During the battle against the two Israeli destroyers, Tamsyn said his ship fired 64 4″ rounds and was certain some had been hits (actually neither Israeli ship was damaged).

Regarding his surrender, Tamsyn said that one-on-one, a Z-class already outmatched a Hunt class, let alone double-teamed. His primary considerations were that both main gun turrets were in limited condition at the end of the battle, one of the boilers was destroyed, the electrical system was disrupted, and the ship could not steer. He also felt that a second Israeli air attack was imminent (actually almost all of the Israeli air force was in action over the Sinai and it was lucky that even the two Ouragans were available). When the promised Syrian fighter cover never showed up, he decided that further delay would only cost more lives.

Tamsyn refused to divulge anything about overall Egyptian strategy but in any case, by the time the debrief was processed, the Suez conflict was about over anyways. The actual intelligence captured aboard the ship was negligible. As far as it’s physical equipment, there was no value at all as the Israelis themselves were using the same WWII-vintage Royal Navy gear.

Tamsyn was criticized in the worldwide military press for allowing his ship to be captured intact instead of trying to scuttle it. To a degree this has some merit but scuttling a warship is not a “push-button” thing; it takes at least a small amount of time and every additional moment saw more Israeli shells incoming. Tamsyn’s age (27) was called into question as it seemed a bit young to be commanding one of the Egyptian navy’s largest warships.

Surprisingly, the place where Maj. Tamsyn was criticized the least was Egypt. The Egyptian public largely saw him as being sent on a fool’s errand and then lied to by his own admirals during the battle; but none the less, he managed to evade three navies undetected and attack the Israeli navy’s home base, before succumbing to superior numbers. He fought with courage given the situation, and managed to get most of his men back home to their families. As for the WWII-vintage vessel, many Egyptians didn’t view it any different than the dozens of tanks and howitzers the Israelis captured intact in the Sinai. Maj. Tamsyn was not disciplined and went on to have a normal career in the Egyptian navy.

The Israeli evaluation of their own part in the battle was positive. The only criticism was that a torpedo boat squadron in Haifa was not released in time as it was assigned anti-frogman duties. Supplies of WWII-made British 4½” ammunition was called into question, as both INS Eilat and INS Yaffo had defective shells or shells that flew erratically.

Because the inquiry was classified at the time, many Israelis thought Kersaint had hit ENS Ibrahim el-Awal and caused the Egyptian ship to cease bombarding Haifa. After the incident, Kersaint‘s captain was toasted and presented ENS Ibrahim el-Awal‘s flag.

To Israel

After repairs, the war prize was commissioned into the Israeli navy as (appropriately enough) INS Haifa.

(INS Haifa in Israeli service.)

As the Israeli naval ensign was raised aboard INS Haifa, in one instant the country’s destroyer force increased by 33%. While a welcome addition, this was a big additional manpower requirement and the ship was manned partially by active-duty sailors, partially by reservists, and partially by cadets of the Israeli Naval Academy in Acre.

(Ship’s crest of INS Haifa.)

In 1961, INS Haifa made a goodwill tour of the Mediterranean, visiting France, Malta, and Italy. The Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser had inexplicably delivered to the Egyptian people the account of a fictitious bombing raid against Haifa that supposedly resulted in the sinking of INS Haifa pierside. The Egyptian air force was embarrassed several weeks later when foreign newspapers on sale in Cairo had a photograph of INS Haifa arriving in Valletta, Malta.

One curious item aboard was the ship’s visitor book, an unofficial register that foreign guests could sign. Quite surprisingly, INS Haifa still had onboard the original WWII Royal Navy volume; having survived aboard uninterrupted as the destroyer passed from Britain to China, back to Britain, then to Egypt and finally Israel. During INS Haifa‘s visit to Malta, a visiting Royal Navy officer pointed out where he had previously signed in while the destroyer was Egyptian.

Generally during the 1960s INS Haifa backed up the other two WWII-vintage Israeli destroyers as a training ship, however there was one more war in the old ship’s future, against it’s former owner.

The Six Day War

In the summer of 1967 all of Israel’s Arab neighbors were gearing up for another conflict against Israel, and it was a question of when, not if, the war would start and who would initiate it. The Israeli military began planning a preemptive strike to catch the Arab armies before they themselves could attack.

On 20 May 1967, LtCol Yehuda Ben-Tzur was notified that he was immediately made captain of INS Haifa, which he had served aboard earlier in his career. At the time, the destroyer was in reserve and at least before the tensions ratcheted up, Israel was planning on scrapping the ship. Ben-Tzur’s orders were to make the vessel combat-ready as fast as possible.

(Yehuda Ben-Tzur, captain of INS Haifa during the 1967 Six Day War.)

Arriving at his new command, Ben-Tzur found the ship in less than ideal condition. The ship’s Quartermaster, who had been acting captain, said that INS Haifa was in “Ready-20” status, meaning it could be brought back to full operation in under twenty days. The skeleton crew only had 20 men; Ben-Tzur immediately requested reservist call-up’s for a full crew. The boiler which had been repaired in 1956 was tagged “for emergency use only”. There was no ammunition aboard and less than 10% fuel. One positive note was that in the mid-1960s a communications upgrade had been done, and INS Haifa now had a modern single-sideband radio replacing the WWII crystal set. The WWII twin 40mm mount had been replaced by two modern Bofors single 40mm guns.

Working almost around-the-clock for two and a half days, Ben-Tzur managed to bring INS Haifa back to life. New conscripts were tasked to help before their training; also helping were workers from the merchant terminal in Haifa. Over 1,000 rounds of 4″ ammunition was hand-loaded, along with boxes of 40mm rounds. The boiler was inspected and brought back online. Several tons of food and supplies were hauled aboard as the ship’s fuel tanks were pumped full. On 22 May 1967, INS Haifa pushed off the pier for a brief sortie in and out of Haifa to prove her seaworthiness, before returning to be drydocked for structural upkeep.

During the upkeep, the main radar was changed to the Bani’ia system, a militarized version of the Decca 12. This radar could detect large aircraft out to 50 NM and low-flying fighters and surface ships to 25 NM. As work was proceeding, the diplomatic climate was deteriorating and war seemed increasingly likely. INS Haifa left drydock on 26 May. On 4 June 1967, the destroyer was ordered to sea, and to expect combat. The turnaround was remarkable, only 15 days separating the mothballed, run-down condition and a combat-ready ship on patrol.

(INS Haifa at sea.)

In the evening of 5 June 1967, Ben-Tzur ordered his crew to battlestations as they were slowly approaching the Egyptian sea border. At 08:00 on 6 June, lookouts reported high-speed aircraft overhead. Almost immediately, the radio room received a message that operation “Focus”, the preemptive air attack against Egypt, had started 15 minutes earlier and that Israel was now at war. The secrecy of “Focus” was such that even inside the Israeli military, not all units were alerted until the operation was underway. The planes had been Israeli strike jets returning after bombing Egypt. INS Haifa was ordered to guard Israel’s coast.

That evening, INS Haifa was ordered to proceed to Tel Aviv which reportedly was being shelled from the sea. The destroyer raced to the area only to find that nervous coastal gunners were shooting at moonlight reflected off the waves, and assuming that one another’s noise was coming from the sea. Afterwards, INS Haifa was warned to be wary of Egyptian submarines and began using classical WWII zig-zag maneuvers.

At 09:00 on 8 June, INS Haifa was 15 NM offshore of Atlit, Israel when a lookout reported a possible periscope 3 NM away. The destroyer’s sonar picked up what appeared to be a submarine, and a depth charge attack was ordered. As INS Haifa passed over the position, four WWII-vintage depth charges were dropped. The explosions blanked out the sonar temporarily. After the destroyer doubled back to investigate, no sonar contact could be established. The water appeared dusty and a rubber gasket was retrieved. Ben-Tzur radioed that he had damaged or sunk a submarine.

(A fairly remarkable photo during the Six Day War, as INS Haifa drops WWII-vintage depth charges on the suspected submarine, while a supersonic Mirage III fighter roars overhead. This shows the newer, single 40mm guns installed after the capture. The sailors are wearing WWII British Mk.II Tommy helmets which were passed down from the Israeli army as it transitioned to newer headwear.)

For certain no Egyptian submarine was sunk during the war. It’s possible the contact was just background noise. However, supposedly the Mossad intercepted an Egyptian request to the USSR for submarine repair parts after the cease-fire. Many years later, a former Egyptian submariner said that in 1967 his sub had evaded undamaged a depth charging from an unknown destroyer. Given the passage of time and secrecy of the Egyptian and Israeli militaries, it will probably never be known for certain.

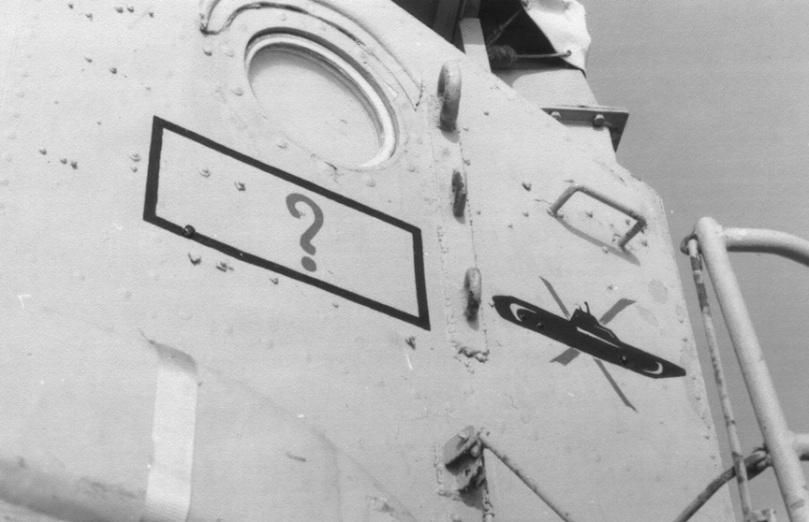

(The “maybe?” battle decoration for the suspected submarine encounter.)

After the submarine incident, INS Haifa pulled into Haifa for fuel. By now the war was more than half-over. The rest of the conflict was uneventful for the ship. On 11 June 1967, the morning after the cease-fire, INS Haifa stopped a suspicious fishing boat off the occupied Gaza Strip. Aboard were three Palestinian fishermen and three Egyptian soldiers, apparently marooned in Gaza when it was overrun. The Palestinians were given a warning and sent on their way. The three Egyptians were taken as POWs, the last POWs of the war. Until they could be delivered to MPs ashore, they were treated as something of honored guests and even signed the old HMS Mendip visitor’s book, the last foreigners to do so.

(The Egyptian army POWs and INS Haifa crewmen share a smoke break on the journey back to Haifa.)

End of the road

The Six Day War was the last call for this veteran ship of WWII. Four months after the war, the Egyptian navy temporarily violated the cease fire to sink INS Eilat with a SS-N-2 “Styx” ship-to-ship missile. With such missiles now in the Arab inventory, the Israeli navy decided to abandon large blue-water combatants in favor of high-tech coastal attack craft and submarines.

In 1968, INS Haifa was placed back into reserve. Some of the weapons and electronics were stripped off the ship. The former destroyer was assigned to the Gabriel I missile development program, alongside INS Nogah, which had been the US Navy subchaser PC-1188 during WWII.

(The Gabriel I anti-ship missile.) (Israeli Defense Forces photo)

INS Haifa‘s final months were spent as a floating barracks for personnel involved in the Gabriel I project. On 7 April 1969, the stripped hull was relegated to a calibration target, then finally live-fire target, for Gabriel I missiles. With that, the long career of this WWII destroyer came to an end.

Interesting article, thanks!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Rifleman III Journal.

LikeLike

A very informative post, thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just want to say, I think this blog is one of the most interesting reads out there. Thank you

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you!

LikeLike

An undignified end to a great lady.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is one of the best sites for WWII and Cold War folks. Thank you so much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this article. Great read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am looking for model plan drawing of the ship

LikeLike

Hi Noam, I believe you can find the general Hunt class line drawing online.

LikeLike

It was nice to read about the ship

LikeLike

Hello, can you please contact me? I’d like permission to use a couple of these photos in a table top game book I am writing on 1956 Suez.

Thank you

LikeLike

hi Kenny, if I know the sources of the photos I put them behind the caption; otherwise I dont know who the copyright holder is.

LikeLike

[…] JULY 13, 2016 JWH197513 COMMENT […]

LikeLike