(part 2 of a 2-part series)

(The 1945 decommissioning ceremony of USS Tunny (SS-282), showing the blown plastic preservation technique on the deck gun.) (official US Navy photo)

(Protective grease is applied to machinery on a mothballed warship, in a still from a post-WWII training video.)

(Mothballed WWII destroyers at Charleston, SC in the 1950s, with their radars removed and AA guns enclosed in igloos.)

Previous US Navy experiences with mass mothballings of warships

post-Civil War

The end of the Civil War in 1865 was the first time that the US Navy found itself with a surplus of warships not needed for peacetime. This was the first baby steps in developing the science of inactive warship preservation. Warships decommissioning in the late 1860s were moved to new reserve anchorages, such as League Island at Philadelphia, PA. There, ammunition was offloaded, mothballs hung inside the ship to deter insect damage to wood (the origin of the term), some movable parts were given a coat of grease, hatches were boarded over, and that was it.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1899, the US Navy attempted to reactivate these ships to guard the USA’s eastern seaboard while the modern fleet fought the Spanish. To it’s dismay, the US Navy found that many mothballed Civil War warships had deteriorated to uselessness, and others were reactivated with great difficulty, sometimes not in time to even participate in the war.

The photo above shows USS Iowa (BB-4) across Philadelphia harbor from two mothballed Civil War ironclads, USS Lehigh and USS Montauk, in 1900. During the Spanish-American War, both ironclads had briefly been reactivated with great difficulty. Both were decommissioned again and scrapped shortly after this photo.

post-WWI

At the end of the First World War in 1918, the US Navy again found itself with a glut of surplus warships. Compared to 1865, the situation in 1918 was more acute as these ships were brand-new, modern, and expensive. Congress was determined that these ships not go to waste. Unfortunately only incremental progress had been made in preservation techniques. As much as possible, guns were covered, hatches were sealed, and pans of slaked lime were placed inside the ships to deter humidity damage. The reserve anchorages became known as “Red Lead Rows” after the red lead-based primer which soon showed through peeling grey paint.

The first call for these mothballed ships came in the 1920s, with the US Navy’s “destroyer swap” program. A worn-out destroyer was paired with a mothballed “twin”. The crew of the original destroyer reactivated the mothballed one using parts stripped off the active one. The original destroyer was then decommissioned and the crew moved aboard the reactivated one and took it to sea.

This was unsustainable as it reduced the destroyer inventory by a factor of ½ each time. The ships themselves were in worse condition then had been anticipated. Soon after the project’s completion, the Great Depression started and the US Navy’s inactive ship budget fell dramatically.

The second major call-up came in September 1940, with President Roosevelt’s “Destroyers For Bases” treaty. Fifty mothballed destroyers were transferred to the Royal Navy. By now, many had been mothballed for two decades and it showed. There was severe rust, especially in areas where rainwater had been allowed to stand. Wooden items were swollen and rotten. Guns were rusted into place. The undersides of the hulls had severe barnacle growth, some so much that the destroyer’s top speed fell by 2 or 3 knots. The wiring (largely still fabric-insulated) was often shorted out and some needed to be completely re-wired. Over the years, crews of active ships had “midnight requisitioned” spare parts off the mothballed destroyers without filling out paperwork, so the reactivation teams had no idea what parts would be missing when they started a ship. Some reactivations took six months; others needed remedial work by the British or Canadian navies.

The post-WWII process for warship inactivation

During WWII the quiet post-war planning group of the US Navy began studies on how not to repeat the “Red Lead Row” mistakes after this war, even as it was still being fought.

In January 1944, a small “Readiness & Care of Inactive Ships” team was formed to develop new mothballing technologies for when peace finally came. On 15 January 1944, the US Coast Guard decommissioned the old cutter USCGC North Star (WPG-59) and transferred the ship to the US Navy for use as a mothballing guinea pig. Thereafter the team was informally called “The North Star Group”. After Germany’s defeat, the ex-North Star was joined in 1945 by USS Seattle (IX-39), a woefully obsolete former cruiser, and the AVC-1, a discarded seaplane catapult barge.

(USCGC North Star while still on active duty.) (official US Coast Guard photo)

(The test hulk ex-USS Seattle (IX-39) during preservation technique experiments in NYC in 1945.) (photo by Mike Green)

Throughout the summer of 1945, the North Star Group experimented on these ships, produced manuals and training books, and developed the systems needed for after Japan’s surrender in August. Besides technical knowledge, a “sailor’s know-how” was needed; for example, an angle iron showing horizontal on a warship’s blueprint might invariably bend in service, creating an area where rainwater would pool up.

With the end of WWII, the North Star Group produced several volumes of training literature, and established two temporary schools to train sailors for the upcoming task. The repair ship USS Laertes (AR-20) was temporarily reassigned as a specialist mothballing mother-ship.

USS Laertes‘s last job was herself, going into reserve in January 1947.

Pre-deactivation

The first step of the the mothballing effort was getting the ship to it’s deactivation port. This was done parallel to, and in combination with, operation “Magic Carpet”, the 1945-1946 mass sealift of soldiers from Europe and the Pacific back home. By Christmas 1945, 240 of the 340 WWII frigates were back in CONUS (the continental USA) and another 94 were en route, and 173 of the 300 destroyers of the Pacific Fleet were in CONUS.

The great majority of the work in mothballing a WWII ship was done by the final crew, which in most cases was rapidly depleting due to wartime enlistments ending. At a certain point, the ship would become uninhabitable by the crew due to the galley, plumbing, and ventilation systems being mothballed. At that time either a berthing barge or ashore barracks had to be arranged while the rest of the work was completed. As there were a limited number of barracks bunks and mess halls available, this took a coordinated scheduling effort.

Pre-mothballing repairs

Any battle damage or broken-down equipment was repaired. This was viewed as a key item. While it might seem odd to spend money fixing a ship about to be taken out of service, experiences with the “Red Lead Row” showed it to be extremely necessary. After WWI, many destroyers went into mothballs with broken-down engines, shaft bearings, capstans, etc. When they were reactivated ten or twenty years later, crews were unpleasantly surprised to find these problems. In most cases, the issue had not been logged, so the reactivation team had no idea what was even wrong.

After WWII, ships heading for mothballs had all repair issues divided into categories. All of the “middle” categories were repaired regardless of expense. Breakdowns in the least important category, which would not prevent the ship from going to sea, were sometimes left as-is to save time, but, properly logged. Damage or breakdowns in the most severe category were repaired on a case-by-case basis – such as the heavily-damaged USS Franklin (CV-13) – or in some cases, disqualified a ship for mothballing and it was immediately scrapped.

The photo above shows repair scaffolding around the superstructure of a cruiser before being put into reserve in 1946.

Offload

Common sense dictated that all ammunition be removed, along with the crew’s small arms. The fuel tanks were pumped dry, as were potable water tanks. All gas masks (WWII warships were not NBC-tight) were removed and warehoused ashore, as were life rafts.

In the above photo, a cruiser’s final crew offloads supplies. The 20mm AA gun nearby has already been removed, leaving an empty gunshield.

Of what remained, perishable goods were identified and offloaded. The US Navy in 1945 defined “perishable” as any equipment which would degrade in storage after 36 months. This included electrical batteries, unvulcanized rubber, paint, medications in the sick bay, and other miscellaneous items. At least in theory, a fireproofing “house cleaning” was done where unauthorized things like cushioned chairs, carpeting, and other flammable material invariably brought aboard was removed. The wardroom’s silver service was also offloaded; a small office of Naval Supply Command (the Silver Program) was established specifically to receive silver services. If the ship was reactivated it was reissued; otherwise it was donated to a museum or held for a future namesake – many Cold War-era or 21st Century US Navy warships have silverware from WWII vessels of the same names.

In 1918, it had seemed logical at that time to offload all repair parts off the “Red Lead Row” vessels as they decommissioned. This turned out to be problematic, as when they were reactivated for the British in 1940 the warehoused parts ashore were long gone and it caused a supply chain bottleneck to get a new loadout of repair parts.

After WWII, the US Navy was not going to repeat this mistake and any non-perishable repair part was left aboard to shorten the time it would take to reactivate the ship. Along these lines, control of the mothballed ships was (at least in the beginning) strictly adhered to, so that they would not be stripped of parts in “midnight requisitions”.

Hull

Surprisingly to some people, the part of a mothballed ship’s hull receiving the worst corrosion is not submerged bottom, but rather what is called the foamline, a few inches above the waterline. The ocean breeze constantly picks up tiny droplets of seawater which then come to rest at the foamline, where they instantly evaporate and deposit salt. On an active warship, this effect is less pronounced as the ship’s draught changes from day to day and in any case, the ship is also often in motion. For vessels in the post-WWII reserve fleet however, the same one or two inches remained the foamline for years or decades at a time, eating away at the steel as can be seen on the inactivated submarine below. If at all possible, warships being mothballed after WWII had an extra-thick layer of paint applied at the foamline.

To discourage barnacle and algae growth, a toxic paint was tried on the ships undersides during their inactivation drydocking that would deter “organic fouling” by brute poisoning. This feature was not successful and would, of course, be unthinkable today. A more subtle approach was sheathing the underside of the hull in plastic during the inactivation drydocking. This was too expensive and soon abandoned.

All hull openings had flanges bolted or welded over them. To protect the hull’s metal itself, zinc bricks were affixed to the hull. Called “sacrificial protection”, the zincs corroded much faster than, and in place of, the hull’s steel. The downside was that the zincs needed to be replaced every few years requiring drydocking of the mothballed ship.

The most effective development in the years after WWII was electric cathodic protection. This involved hanging wires and anodes charged by a slight current off the sides of ships. This replicated the role which the zincs had previously filled, but, the protection time was quadrupled lessening the need for drydocking of mothballed ships. The technology was further refined so that one set-up could protect a clustered nest of ships. Electric cathodic protection greatly extended the lifespan of the mothballed WWII warships and the technique is still used today.

One of the most defining symbols of the US Navy’s reserve fleet was the large draught marker. This was a white V (usually 31″ tall) bisected twice by horizontal lines. Ideally the tip of the V met the intended mothballed waterline. This simple idea allowed personnel ashore to monitor any draught changes far away with binoculars. The white V continues in use on inactive US Navy ships today in the 21st century. Below is a V on the WWII destroyer USS Watts (DD-567), decommissioned in 1946 and later reactivated for the Korean War in 1951; serving until 1964.

Some of the more valuable mothballed ships had internal flooding alarms. Initially, a battery-operated buzzer was placed into styrofoam balls. If a compartment flooded, the ball would float, tipping over due to the buzzer’s weight and sounding it. Later an electronic scoreboard-type setup was devised. These were banks of red/green traffic signals hung on the nearest ship of a cluster or nest, indicating any problem.

Exterior

For any surface exposed to the weather, a prime concern was not letting rain or snow melt pool up. Any dent, depression, etc on the main deck was either leveled or coated with an epoxy. In some cases, features which would collect rainwater had small holes drilled in the bottom to permit drainage. On the mothballed escort carriers, some were given an intentional 1° list to encourage rainwater runoff from the flight deck. On most large ships the bridge windows were boarded up, on smaller or less-valuable vessels they were covered with tarp.

Naturally, ships with wooden decks (carriers, battleships, and some cruisers) needed extra care. Two approaches were tried. Agricultural herbicide was sprayed on the wood; this protected against mildew and moss but not weather. The other concept was peelable plastic, which is just what it sounds like. This was usually done to carriers only, as it was very expensive.

The above photo shows USS Cape Esperance (CVE-88) being reactivated for the Korean War in 1950. This gives an excellent view of one of the “igloo” structures and also shows residue from the peelable plastic on the wooden flight deck.

Experiences with the “Red Lead Row” destroyers in 1940 indicated that giving a decommissioning warship a regulation ‘ship-shape’ paint job accomplished little in the long run. To that end, after WWII crews were instructed to paint for preservation, not cosmetics, and many mothballed ships had an irregular “touched-up” look, as seen on the gun tub of USS South Dakota (BB-57).

Rust Preventative Compounds

Three types of rust preventative compounds (RPCs) were developed by the North Star Group at the end of WWII. This concept was not new, an earlier RPC had been developed after WWI and applied to some “Red Lead Row” ships. This early RPC lost effectiveness after time, and more importantly, became a problem itself as after years it was difficult to remove when the ship was reactivated. All three of the new types were removal-friendly.

The first new type was used on topside equipment. It was applied as seen above.

The second type was used in the ship’s interior, and had a lubricant so that it could be poured onto gears, transmissions, power shafts, etc. as seen above.

The third type was a heavy-duty version of the first, and was intended for surfaces which would directly contact water, such as bilges. It could either be sprayed on or poured.

Specialized structures

More than anything else, the “igloos” installed over AA gun positions came to symbolize the post-WWII fleet in reserve. The igloos were made in prefabricated sections, like orange peels, and assembled on a base ring. The igloos were made first of tin, then as WWII aircraft contracts were cancelled and aluminum became plentiful, of that metal. Aluminum had the advantage of being rustproof, and was also lighter and easier for sailors to manhandle the pieces. The pieces were held together by silicone putty which also waterproofed the seams.

Some igloos came with a small access door and/or a view window. In other cases, a hole was cut and a door from warships being scrapped was installed, then sealed in place with putty. Before the igloo was completely sealed up, it was aired out and in some cases, desiccant placed inside.

(The cruiser USS Dayton (CL-105) having an igloo installed after WWII. Also seen is a temporary wood deckhouse to store various items; these were sometimes built on larger ships to save space in ashore warehouses.) (Associated Press photo)

The igloos were sized to be commonly compatible with all 40mm gun mount positions, and also the Mk15 version of the Hedgehog ASW weapon. For 3″ weapons like the twin-barrel Mk33, and single-barrel 5″ gun versions in open mounts, extensions could be grafted onto the igloo to enclose the gun barrel.

(An igloo on USS Hornet (CV-12) with an extension for the 5″ gun’s barrel. A “can”-style enclosure is behind it.) (photo by Sarah Lanzaro)

The igloos were intended to be single-use but during the mothballed ships inactivity periods, sailors discovered that if care was taken, they were sturdy enough to be lifted off in one piece and later reinstalled. These cheap, simple objects were tremendously successful.

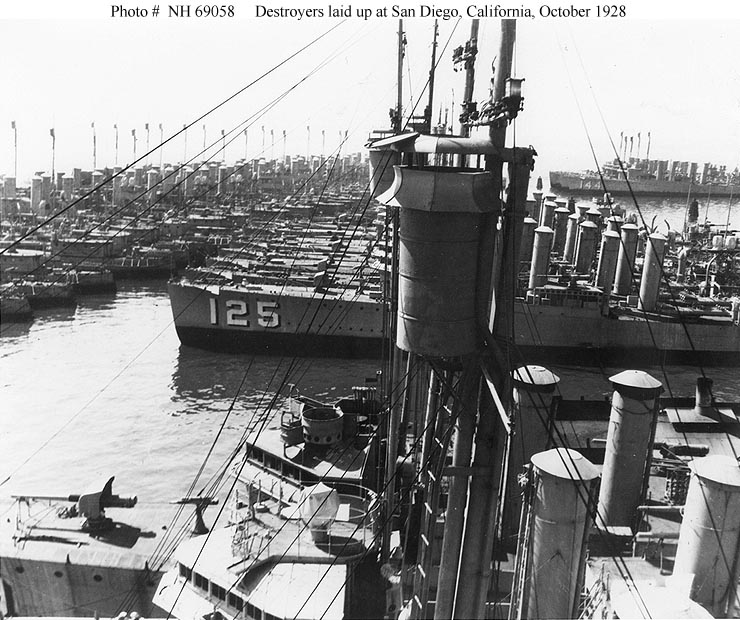

(Mothballed destroyers and frigates at San Diego, CA five years after the end of WWII.) (photo via navsource.org website)

The government stopped supporting the igloos in the supply chain on 1 January 1963. However needing no maintenance, the installed examples remained watertight for decades, and it was still common in the 1980s to see mothballed ships with intact igloos erected in the 1940s. The hemispherical design ran off rainwater evenly, discouraged snow build-up, and resisted winds of the strongest storms.

Above is the decommissioned USS Atlas (ARL-7) and USS Amycus (ARL-2) in mothballs at Stockton, CA. These were repair vessels to service damaged LSTs and were unneeded after WWII. Both decommissioned in 1946 and were mothballed. USS Atlas was reactivated for the Korean War, then put back into mothballs, and finally scrapped in 1972. USS Amycus was never reactivated and was scrapped in 1971. This photo shows igloos over their stern AA gun positions. Their davit arms are empty, with the workboats being stored ashore.

There were other structures, less common, with similar roles. One was nicknamed the “can” and was usually used over optical devices. Another was named the “doghouse” and was constructed of aluminum. These were set atop things like AA gun directors, searchlights, mushroom vents, deck motors, etc. Doghouses were also often set over hatches which the caretaker crews needed to periodically access; other hatches were caulked shut. The photo above shows a 36″ searchlight aboard a mothballed cruiser in a doghouse.

(photo by Betty Simons)

The photo above shows the Benson class destroyer USS Hobby (DD-610) at the Orange, TX anchorage in the 1960s. A veteran of the Iwo Jima and Okinawa battles in 1945, USS Hobby was placed into mothballs on 1 February 1946. The house-like structure (common at the Orange facility) protected the upper bridge, Mk37 director, optical rangefinder, and Mk12 radar all in one move. It’s own weight and shape held it snug against the destroyer and only one crane lift would be needed to reactivate all these things. After decades in mothballs, USS Hobby was never reactivated and was sunk as a target in June 1972.

Blown plastic

Plastic was not new by the time of WWII, but was still in limited use. The mothballing effort was the US Navy’s first large-scale adventure with plastic. A system was devised to protect topside features not covered by the igloos or other structures.

First, a thin form-fitting sheet of plastic mesh was laid over the object. Shown below is the start of the procedure, in this case on a submarine’s AA gun.

After this was secure, five layers of blown liquid plastic were applied to the mesh, forming a protective shell. Shown here is a 3″ gun on an auxiliary.

Finally, a small hole was drilled and any remaining moisture extricated. The last step was to paint the plastic shell with a topcoat of aluminized paint, which prevented the plastic from “breathing” during temperature changes, and also stopped the sun’s UV rays from making it brittle.

The finished product is seen above, in this case the Mk11 5″ guns of USS Brooklyn (CL-40), along with various AA gun directors and other deck items. Also of interest, unrelated to the plastic process, is USS Brooklyn‘s wooden seaboat. After WWI, smallboats on the “Red Lead Row” ships were just covered in canvas. This sagged after a while, pooling up rainwater which eventually leaked through damaging the boat. After WWII, smallboats on inactivating ships were painted, topped with tarpaper, then covered with a steepled roof to run off rainwater.

Although somewhat less long-lived then the igloos, the blown plastic system was also highly effective, able to cover hundreds of different types of oddly-shaped features very fast and inexpensively.

Interior

Inside the ship, watertight doors not meant to be opened were shut and had baling wire run through their dogs. They were then sealed with caulk.

The galley’s freezer and the ship’s air conditioning system (for the limited number of WWII ships with that onboard) were bled off of freon. Items such as navigational tools, bridge phones, etc were usually removed and taken to areas of the ship less susceptible to moisture and theft. In each case, a tag was affixed detaining the removed item and where it was stored, and also on the item telling where it belonged. Tech manuals were removed to ensure that the most current edition was used if the ship recommissioned.

The biggest enemy inside a mothballed ship is humidity.The US Navy tried to keep the ship’s interiors at a stable 25% humidity. The photo below is a still from a 1945 training video on mothballing warships, and shows a mooring line which has rotted due to being stored in a humid environment.

The US Navy developed a shipboard dehumidifier for the reserve fleet. These were placed in logical locations, and then fed by a network of temporary ducts run throughout the ship, as on the cruiser below.

One dehumidifier was sufficient for a minesweeper or frigate, while six were needed for a large aircraft carrier. For dehumidified ships, maintaining an “external moisture boundary” was extremely important. A vertical hole the size of a half-dollar coin could introduce enough rainwater to overwhelm the dehumidifier.

For sealed compartments, voids, etc; the compartment was first aired out. Then a disc of desiccant was placed inside and the compartment sealed up. The discs were periodically changed out, otherwise nothing else was needed.

A final step was ensuring the ship’s key locker was up-to-date and properly labelled. Although it seems minor, during reactivation of the “Red Lead Row” ships a constant distraction was having to punch out and replace machinery locks for which keys could not be found.

Engines

For steam-powered ships, the boilers were run up to a full head of steam which was then bled outboard until the water tanks were emptied. The fireboxes were then extinguished, cleaned, and closed up.

After WWI, the procedure for the “Red Lead Row” ships had been to partially disassemble electrical panels, completely slather them in grease, and leave the housings off to prevent humidity from building up inside. In the 1920s and then again in the 1940s, this was discovered to have been counter-productive as the exposed innards rusted only slightly slower than leaving them intact, and the huge amounts of grease had to then be cleaned out if the warship was reactivated.

After WWII, electrical panels were cleaned, sprayed with a fungicide (most electrical insulation in the 1940s was of fiber or natural rubber), then properly sealed back up, ready for immediate reactivation.

The ship’s stacks were covered with 16ga sheet metal. External air intakes were blanked off with flanges. Underwater, a “boot” was sometimes applied over the propeller shaft seals for added protection, and the shafts locked.

Above are USS Iowa (BB-61) and USS Intrepid (CV-11) at San Francisco, CA in the 1950s, showing the caps on the stacks. USS Iowa also has temporary wooden deckhouses to store topside equipment; on USS Intrepid the same gear was moved to the hangar deck. Both of these warships were later reactivated and both survive today.

For diesel-powered ships, an anti-corrosion chemical was developed which was poured directly into the diesel engine. This chemical was self-cleansing in that if the ship was reactivated, running the diesel for two hours purged it.

Weapons

For major (12″-16″) caliber and medium (5″-8″) caliber guns, the muzzles were plugged and then sometimes sealed in oiled canvas or plastic wrap. The turrets were prepared in the same way as the ship’s interior. All on-mount optics were removed and warehoused ashore.

Guns of 3″ caliber, and some older open 5″ guns, were either shut in with an igloo or encased in blown plastic.

The very common 40mm AA guns were given a final cleaning and oiling, and then enclosed in igloos or covered with blown plastic. Sometimes the barrels of the 40mm guns were unscrewed and warehoused ashore.

The 20mm and .50cal guns were better preserved in ashore warehouses, and in any case smaller and more easily stolen. These were almost always removed during the inactivation. The empty mounts were either enclosed in igloos or blown plastic, or, themselves taken ashore.

Above is USS Tennessee (BB-43) during the summer of 1946. The empty gunshields for the 20mm AA guns are on a railroad car on the pier, with the guns themselves already taken to a warehouse. Meanwhile the 14″ main guns are capped and sealed, while workers are applying paint to the seams of the 5″ turrets. The 40mm AA guns are covered with blown plastic. This also shows the life rafts ready to be craned ashore, and the “touched-up” look of the pre-inactivation painting on the superstructure.

Anti-ship torpedo tubes were purged of compressed air. Little else was done to protect them as the era of destroyers dueling with unguided torpedoes was fading into history.

Depth charges were offloaded but their racks were left onboard, as they were fairly simple structures that deteriorated slowly, and this saved time when the warship was reactivated.

Sensors

Originally, the WWII radar and radio antennas were left in place. These physical items were designed to withstand gale-force winds and were deceptively strong. As years went on, various forms of degradation started. Not being rotated regularly caused radar dishes to settle down on their bearings, and an unpleasant side effect of seagulls resting on them was a cascade of acidic bird droppings on the antenna. Starting in the 1950s, many mothballed WWII ships had their radar dishes removed and warehoused ashore. All of the internal circuitry and displays were cleaned and left as-is to lessen the time needed to reactivate the warship.

Above is a nest of mothballed WWII-era cruisers in the 1950s, all missing their radar antennas which had been warehoused ashore.

Electro-optical devices, such as the lead-computing sights for AA guns, were usually removed for storage ashore, or covered with blown plastic.

Submarines

Mothballed submarines had unique requirements. Making them watertight was extra-important, as they had little reserve buoyancy to begin with. Ballast tank valves and torpedo tube breeches were lockwired shut, and hull openings flanged over. Since a submarine relies on silence for survival, marine growth on the propellers would be problematic as it would cause cavitation when the submarine was reactivated. To that end, the propellers were removed and stored ashore. Periscopes were pulled out and warehoused ashore; with their openings flanged over. This both protected the expensive lenses and also eliminated a possible leak source. The batteries were drained of electrolyte, and compressed air tanks bled out. The light AA guns were either removed ashore or covered in blown plastic, while the main deck gun was covered with an igloo.

The photo above shows mothballed WWII submarines at Groton, CT. The submarine on the right is USS Cavalla (SS-244) which had sank the aircraft carrier IJN Shokaku during the war. This reserve anchorage on Connecticut’s Thames River was ideal, as the flowing freshwater deterred barnacle growth. The facility was adjacent to Submarine Base New London and across the river from the Electric Boat Company shipyard, so it was an excellent location for quick reactivation of the submarines.

Wooden ships

The US Navy at the end of WWII still had wooden-hulled vessels in use; most notably minesweepers, yard service boats, landing craft, and of course the famous PT boats. An entire procedure was developed for preserving wooden craft in reserve. The smallest of the types were craned ashore. For the others, all minor equipment was removed, and a rot-inhibitor sprayed onto the hulls. On minesweepers, the rust preventative compound was applied liberally to winches, reels, etc. Smaller craft, such as the PT boat below, were covered with a ventilated oiled canvas apron to run off rainwater.

The photo above from the November 1945 issue of All Hands magazine shows an optimistic outlook for mothballed PT boats. The reality was somewhat different. With no tactical niche in the postwar navy, PT boats were viewed as much of a burden as asset. Over 100 of them were destroyed in the Pacific to save the expense of shipping them back to the USA. The photo below shows a row of PT boats at Samar, Philippines after the end of WWII. They were stripped of any and everything useful, driven aground at high tide, then burned at low tide to further recover remaining steel.

The same largely held true for plywood landing boats, wooden yard punts, and the such. During WWII these were viewed as semi-disposable from the start. A procedural maneuver after Japan’s surrender moved them from “vessels” to “command property”, like jeeps or typewriters. This cut the bureaucratic red tape needed to quickly get rid of many of them.

Incomplete ships

Due to WWII’s unexpectedly sudden end, the US Navy had incomplete warships under construction. Generally, those in an early stage were scrapped on the building ways, while a few in late stages of construction were completed. Others, seemingly nearly complete, were themselves discarded, for reasons sometimes hard to decipher. For example at the end of WWII, the cruiser USS Newark (CL-108) was 68% complete, the destroyer USS Castle (DD-720) was 60%, and the aircraft carrier USS Reprisal (CV-35) was 52%. None of these top-line warships were completed or retained; all were disposed of at the end of WWII.

A very small number of incomplete ships were mothballed without being finished. Again, it’s hard to determine any logic as some of these were less further-along than sisters discarded.

Mothballing an incomplete ship was unique. On one hand, obviously steps like offloading ammunition and defueling, etc were not required. However there were challenges. Some ships had gaping holes for weapons or systems not yet installed, these had to be blanked off with sheet metal. Many were not yet fully compartmentalized internally, and dehumidification and flood control boundaries were more difficult.

Above is the Butler class frigate USS Wagner (DE-539), launched during WWII. When WWII ended, the ship was 62% complete and work was suspended. The US Navy hoped for funds to commission the ship in 1946, but this was not to be and in February 1947, the incomplete hull was towed to Boston and mothballed. For 8 ½ years USS Wagner quietly sat unfinished. The ship was finally completed in November 1955, only to be placed into mothballs a final time in 1960, then sunk as a target in 1975. Of USS Wagner‘s 30-year life, 25 years were spent in mothballs. The above photo shows how the incomplete bridge structure was plated over during the 1947-1955 hiatus.

USS Hawaii (CB-3) would have been the third Alaska class battlecruiser. Despite mothballing the first two Alaska class ships, the US Navy was interested in keeping USS Hawaii, a “blank canvas” that might later carry future systems. When construction was suspended after WWII, USS Hawaii was 83% complete, including the main 12″ gun battery and some of the secondary 5″ AA guns.

In 1947, the incomplete USS Hawaii was mothballed at New York Shipbuilding’s Newton Creek facility. In the early 1950s, the hull was towed to NISMF Philadelphia. Much like the never-completed battleship USS Kentucky, a whole variety of ideas were suggested for USS Hawaii during the Cold War: conversion to a fast flagship, or amphibious command ship, or replacing the guns with SAMs, or ASW flotilla leader, and even carriage of ICBMs. None of these plans was ever funded and USS Hawaii was scrapped in 1959. Inclusive of the construction, mothballing, storage, and tow costs; American taxpayers spent $70 million (about $751 million in 2016 dollars) on USS Hawaii.

The first ship

The first test of all these new techniques was the cruiser USS Brooklyn (CL-40). USS Brooklyn was selected as a “representative ship”, being of medium age, medium size, average wear & tear, etc.

On 30 October 1945, USS Brooklyn; already with a shrinking crew due to the personnel demobilization, was moved into the “In Commission (Reserve)” category. All of the procedures described above were done with meticulous care.

On 31 January 1946, the mothballing process was complete and USS Brooklyn decommissioned. By the end of the process, the cruiser’s crew had been whittled down to just the captain, 4 officers, and 59 enlisted men.

For this first ship of the new “ghost fleet”, a unique ceremony was held on 31 January 1946 where an admiral ceremonially threw the switches that started up the dehumidifiers inside USS Brooklyn.

The extremely successful operation on USS Brooklyn served as the template for the rest of the fleet. As for the cruiser itself, USS Brooklyn sat in mothballs for six years and was then successfully reactivated for sale to Chile as ARC O’Higgins, serving with distinction in that navy until 1992.

Completion

The fleetwide effort was largely finished by the autumn of 1947. The total cost of the mothballing project was $99.89 million ($10.8 billion in 2016 dollars), for which was preserved $13 billion ($140 billion) worth of WWII-built warships.

In reserve

Inactivated WWII warships were each assigned a code. Category B was the most-ready; this was originally for the skeleton-crewed ships when the “divisions” concept was still around immediately after the war. Category C was the overwhelming bulk of the ships, unmanned and mothballed but receiving upkeep care, and is what most people think of as the reserve fleet. Category I was a small number of ships out of commission, partially mothballed, and used by personnel of the anchorages to tend to the laid-up ships. Category X meant no upkeep was done beyond ensuring the ship didn’t sink. This was given to vessels of low value or when future reactivation was thought extremely unlikely, and “X” was usually the last step in a warship’s life before the scrapyard.

(photo via navsource.org website)

Above is the deck of LCT-602 in 1946, one of the few Category I ships. An amphibious craft during WWII, after the war it was decommissioned and converted into a “babysitter” for mothballed ships of the “Florida Group” reserve anchorages. The photo shows freezers bolted to the deck to store food for the skeleton crews.

Reactivation

Many of these ships were later brought out of mothballs. An early example was the nameless subchaser PC-823 which had decommissioned in February 1946. In September 1949, citizens of South Korea donated funds to purchase their navy’s first seagoing warship. The ex-PC-823 was reactivated and transferred as ROKS Pak Tu San (PC-701). Later during the Korean War, it became the first South Korean warship to sink an enemy vessel. The photo below shows the reinstallation of a Mk19 3″ gun which had been warehoused ashore at Pearl Harbor after WWII.

The start of the Korean War saw the first big wave of reactivations. Below is the cruiser USS Baltimore (CA-68) being reactivated in 1951 to relieve ships of the Atlantic fleet for service in Korea.

Below is an igloo being disassembled aboard the aircraft carrier USS Monterrey (CVL-26) in 1951 for Korean War reactivation. This had been the ship that Gerald Ford served on in WWII. After the Korean War, USS Monterrey was again mothballed and finally scrapped in 1971.

The above photo from a July 1950 issue of Life magazine shows one of the more trivial aspects of reactivating a WWII aircraft carrier for Korean War service.

The second big reactivation wave came from the GUPPY (submarines) and FRAM (destroyers) upgrade projects during the Cold War. At the same time, vessels not modernized were being sold to allied navies. The Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 resulted in the reactivation of some additional mothballed ships.

A significant number of now-aging WWII ships were reactivated for the Vietnam War. Below is the fast assault transport USS Cook (APD-130). After WWII, USS Cook decommissioned in May 1946 and was mothballed. In October 1953, USS Cook was reactivated and later made seven combat tours during the Vietnam War, being highly decorated by both the American and South Vietnamese governments. USS Cook served until 1969 and was scrapped in 1970.

Sometimes a reactivated ship was not fully reactivated, if the new duties did not need all the systems. Below is USS Lakeland (LSM-373), a WWII amphibious ship mothballed in 1946 and reactivated in 1958. The igloo remains over the WWII-era 40mm AA guns.

In 1946, the US Navy estimated that an average (destroyer, frigate, or light cruiser) mothballed WWII warship could be fully reactivated in 30 days at a cost of $30,000 ($399,328 in 2016 dollars).

In 2000, a private study on the then-dwindling post-WWII reserve fleet estimated that the cost of reactivating a properly-mothballed ship had risen by a compounding 0.5% annually after a three-year baseline. A less-optimistic study several years previous had placed it at 2%. The accuracy of all these estimations should probably be taken with a grain of salt and are hard to prove or disprove. The increase of reactivating an aircraft carrier after ten years was probably much more severe of a slope than say, a barge. Also when mothballed ships were reactivated, they were often refitted with new sensors, radios, etc. which threw off the cost.

The end

With the exception of very large vessels like carriers, cruisers, or of course the four Iowa class battleships; WWII-era warships had inherent limitations for modernization. Radars, sonars, and jammers developed in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s consumed tremendous amounts of electrical capacity and below-decks space for processors. This was often beyond the ability of WWII-era designs. For radars, the antennas of Cold War systems were larger and heavier than WWII sets causing topweight concerns; already in the 1940s topweight growth was a major safety concern in the US Navy. Cold War-era weapons, like guided missiles, often would require reconfiguration of a WWII warship so extensive as to make little financial sense.

Above is the hangar deck of USS Enterprise (CV-6) in 1958, still showing WWII decorations and markings. A pre-war design, USS Enterprise fought all of WWII from start to finish. Decommissioned in 1947, USS Enterprise was scrapped in 1958.

The Mobile, AL anchorage was shut down in the 1950s, with it’s WWII-era ships either scrapped or moved to Orange, TX. The Stockton, CA facility followed shortly thereafter, with it’s remaining ships going up the coast to Suisun Bay.

The first big “purge” came in 1959. Six years after the end of the Korean War, many mothballed WWII ships which had not been called up were disposed of. This included most of the remaining battleships, and the heavy cruisers USS San Francisco (CA-38) and USS Wichita (CA-45), shown being scrapped below in 1959, still with the 1947 igloos in place.

In 1961, the entire “Florida Group”, which still had about 170 mothballed WWII ships in it, was eliminated by Congress and 140 of it’s ships towed to Orange, TX with the balance being scrapped. This had the unusual effect of the Orange facility greatly increasing in size, sixteen years after WWII ended.

Originally in 1946, it was intended that mothball fleet not be used as a self-serve spare parts source by active duty warships, as had happened with the “Red Lead Row” vessels after WWI. As the decades went on however, it became harder to adhere to this. It was difficult to justify to Congress a funds request for spare parts when the same items were available on inactive ships. After the Korean War, the mothball fleet had a “6 & Replace” rule applied, meaning an item could be removed if it was replaced in six months. By the time of the Vietnam War, the US Navy sometimes removed WWII-era equipment itself, as it was by then so obsolete that it couldn’t be supported even if the warship was reactivated.

During the early 1960s, the Groton, CT submarine mothball anchorage was already largely emptied by GUPPY conversions and scrappings, and was rolled into the main New London submarine base. Astoria, WA closed in 1963, with it’s remaining WWII-era ships going either to Bremerton, WA or Suisun Bay, CA.

Wilmington, NC and Charleston, SC were closed in 1968. The “Hudson River Group” in NY was eliminated in 1971. Boston, MA’s South Annex reserve anchorage was closed in 1974, with it’s few remaining WWII-era ships going to Philadelphia.

The second big “purge” occurred in 1975-1976, with over half of the remaining mothballed WWII combatants being scrapped. When Gerald Ford became president in 1974, he was determined to root out waste in the defense budget and upkeep on the ageing WWII ships was viewed as an expendable.

Below is USS McKee (DD-575) in 1972 at the Orange, TX facility. This destroyer had participated in the Rabaul, Marianas, Leyte Gulf, and Okinawa battles during WWII, then was decommissioned and mothballed in February 1946. After 2 ½ decades in mothballs, the destroyer (still in unmodified WWII form) was missing most radar antennas and was rusting.

(photo via navsource.org website)

In 1975, President Ford ordered that the massive Orange, TX site be cleared of it’s mothballed WWII-era ships. Long in reserve, these ships now had little military value and most were towed down to Brownsville and scrapped. The last left in 1980 and the site shut down.

Of the 2,269 warships, submarines, auxiliaries, landing craft, and service vessels which the US Navy had mothballed between 1946-1947; only three dozen remained untouched by the time President Reagan took office in 1980. A larger number of WWII ships belonged to the group which had been mothballed, reactivated, then put back into reserve; or in some cases, never having been mothballed at all.

The final “purge” happened after President Clinton took office in 1993. By now, the few remaining WWII-era mothballed ships were hopelessly useless, and additionally, space was needed at the few remaining inactive ship facilities for modern warships made surplus by the collapse of the USSR in 1991.

(photo from book Warship Boneyards by Kit & Carolyn Bonner)

Above is the WWII salvage ship USS Clamp (ARS-33) in October 1999. Mothballed in May 1947, by the turn of the millennium USS Clamp was severely deteriorated, stripped of some parts, and being used to store spare mooring buoys. This warship had missed the Korean War, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Vietnam War, and Desert Storm; and it was unclear what exactly the government was saving it for. USS Clamp became an unfortunate “poster child” for critics of the National Defense Reserve Fleet, as it is now known. This ship was finally towed to the shipbreakers in 2011. Altogether, USS Clamp spent 4 years on active duty and 64 years in mothballs.

Above is USS Gage (APA-168) being towed out of the James River, VA facility on 23 July 2009, en route to a shipbreaker in Texas. This attack transport had participated in the Okinawa campaign of WWII and then operation “Magic Carpet” in 1945-1946. Decommissioned in February 1947, the rusting USS Gage was the last large mothballed WWII ship on the East Coast.

Below is a troop compartment of USS Gage in 2009, when the vessel was given a final spare parts stripping. This compartment had been untouched since 1946.

The Suisun Bay, CA mothball fleet, largest of them all, became the focus of environmentalist groups in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The anchorage held mothballed vessels of all types, dating from after WWII to after Desert Storm. The older ships were full of lead paint, PCBs, solvents, and above all asbestos. Many of the ships were in terrible condition by the turn of the millennium. In 2011, Suisun Bay’s final WWII-era mothballed ship was towed away and by 2015, only a dozen Cold War-era vessels remained. The Suisun Bay facility began it’s closure in 2016 and will be shut down by February 2017, if not before. With that, the story of the post-WWII mothballing effort will end.

[…] Source: Mothballing the US Navy after WWII: pt.2 […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

A really interesting couple of posts. The whole process from deciding which ships to retain/hold/scrap to decommissioning and mothballing is incredible. The effort it takes to preserve them too is surreal, being more prone perhaps than other military hardware, to corrosive attack, they need an incredible amount of work on them. Aircraft were stored in a desert where conditions were dry so a lot of the corrosive issues were never a problem. War is great for production, but what happens at the end is a major problem. Thanks for the research!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Awesome article! My dad was on the USS Shangri-La (CV-38) on it’s final cruise to Naval Station Mayport in 1971. My parents almost had to delay their wedding, as they stopped the ship for several days offshore to repaint one side so it would look good for the decommissioning ceremony!

One small quibble: Tongue Point is actually Astoria, OR, not WA. I live out that way, been there many times!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wonderful insight into the mothballing process. Thank you for your research and dedication to preserving this important piece of American history.

LikeLiked by 2 people

And some of the ships where put as reefs, such as the Uss Rankin. Or the ralph evinrude reef, Stuart Florida. We did this to eliminate waste and corruption to save the tax payers money. Create work, and honor a great industrial leader.. The waste, fraud and stealing from the tax payers in grace commission report. And GAO.. Stated 34 cents out of every tax dollar was wasted or stolen by government officials and there friends.. Today, its most likely 50 to 60 cents.. Stolen… Sadly. God bless thoses service man that risked there lives, for us to have freedom, safety and a wonderful counrty. The corruption comes from lawyers, like steven.allen@huschblackwell.com / whom cheat there clients with lies, and law breaking to fill his own pockets.. Its, a rat invested society of socially disabled gangsters. Whom, could care less, about law in order and the god given freedom. There only focused area, is more and more money. Protected by crooked political industry of lies, and dishonesty.. The people in America, deserve more. Violence, is not the answer. The answers are knowing the difference between right and wrong. Good and bad… And having faith to do the right thing. For every one and not a select few.. And down to earth communication. I get tears in my eyes, when i hear the senseless killing. And white collar criminals whom now get away with murder.. God bless America, whom are veterans died for… Only to have our country continue there to defraud the taxpayers… Anyone wishing to keep in contact from this old fool from Wisconsin,

wrjusten1@gmail.com

LikeLike

I spent many hours looking at mothballed ships in the 1950/52 when my father was stationed in Bremerton Washington. His duty was on the partiality decommissioned USS Indiana. 5 Battleships among the many heavy and light Cruisers, Destroyers and Carriers were lined up. Lot of history all floating side by side.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I served in the mid-1990s, by then the James River mothball fleet in Virginia was already dwindling.

LikeLike

Oh, you’re ex-Navy, that makes since. I’ve always found your posts about ships highly informative. My father was on the USS Shangri-La in Vietnam. I’ve still got his ship “yearbook.”

LikeLiked by 1 person