During WWII the Mosin-Nagant was the Soviet army’s standard longarm. After WWII, all of the client communist nations in eastern Europe used it. The case of Romania is interesting in that its run predated WWII itself, and continued right to the end of the Cold War in 1989.

(Mosin-Nagant M44 carbine of Romania’s brief post-WWII production run.) (photo via National Rifle Association)

(“Instructie” stamp on a Romanian Mosin-Nagant.)

(Members of Romania’s Gărzile Patriotice (Patriotic Guards) march with WWII Mosin-Nagants during the 1970s.)

the Mosin-Nagant

The Mosin-Nagant, which over the decades came in carbine, long rifle, cavalry, and other formats, fought in both world wars and was the Soviet Union’s standard battle rifle during WWII.

(Soldiers of the communist-era Romanian army during the 1950s with Mosin-Nagant 91/30 rifles. The helmets are WWII Soviet SSh-40 which the Soviets supplied Romania during that decade.)

(The M44 carbine version; this particular gun being a WWII-production Soviet M44 later reblued and restocked in Romania.)

All variants are bolt action, using the 7.62x54mm(R) cartridge from a stripper-loaded 5-round internal magazine. Muzzle velocity varies between 2,625fps – 2,838fps depending on the ammunition and particular model of Mosin-Nagant. The common 91/30 long rifle version has a rear sight incremented out to 2 kilometers (2,178yds) with actual realistic accuracy varying with any number of factors.

(Romanian soldier with Mosin-Nagant during the 1950s.)

Romania during & after WWII

(Map of the Warsaw Pact.)

During WWII, Romania was part of the “minor Axis”, operating in league with Germany and Italy (and later Bulgaria) in eastern Europe.

The Mosin-Nagant was not new to the Romanian army even before WWII. During World War One (which Romania fought on the Allied side), Romania acquired some via foreign aid or battlefield captures. Between the world wars, additional small lots were purchased abroad. By the late 1930s, the nation was self-sufficient in 7.62x54mm(R) ammunition.

When Romania entered WWII the army had two standard rifles: the French-made Mle. 1886-M93 Lebel and the Czechoslovak-made vz24; with the latter being more common.

(King Michael I’s monogram on the action of a WWII Romanian vz24. During the Cold War these were usually buffed away, although curiously sometimes the M and I is obliterated but not the crown.)

The Romanian army also had many Mosin-Nagants, which were considered substitute standard. By the start of WWII in 1939 Romania already had 215,000 Mosin-Nagants in inventory.

(Romanian soldiers with vz24 rifles during WWII. A large number of Romanian M-1939 helmets survived WWII and were widely used by the Cold War-era Romanian army until sufficient combloc headgear was available. During WWII, Germany also donated to Romania Wehrmacht-standard stahlhelms and Dutch M34s which had been captured in 1940. Surprisingly small numbers of each also lingered on into the Cold War.)

The WWII Romanian army was large, peaking at 1.3 million men. On the Ostfront, Romanian forces gave a passable if not spectacular showing early on. They were instrumental in the 1941 crossing of the Prut river and the capture of Odessa.

As WWII progressed, the Lebel rifles were discarded. The vz24s were joined by Mauser 98ks supplied by Germany and Carcano Mod. 91/38s supplied by Italy.

(This ex-German 98k of WWII was used by the Cold War-era Romanian navy.)

The Mosin-Nagant grew in importance. There were already a lot of them, Romania was already self-sufficient in ammunition for that caliber, and huge quantities of Soviet Mosin-Nagant 91/30s were captured by Romania during 1941.

The turning point was the December 1942 – January 1943 Axis disaster at Stalingrad. Romania lost 109,000 men at Stalingrad and the bulk of the nation’s artillery. Another 46,000 were lost in subsequent retreats. The Stalingrad defeat seemed to “break the army” and it performed poorly thereafter. Another entire Romanian battalion was wiped out on the Crimean peninsula in early 1944, and the Romanians were again defeated that year at Odessa, which they had conquered three years previous.

Remaining Romanian forces were consolidated into the Wehrmacht’s Gruppe Süd during mid-1944. In August 1944, Romanian units were pushed out of Chisnău (today the capital of Moldova). Once the Soviets crossed the Dniester river’s remaining tributaries, there would be little stopping them from advancing into Romania proper.

On 23 August 1944 King Michael I led a coup which deposed the pro-Axis Antonescu government. The coup is usually presented today as an unbridled capitulation to the USSR, which in fairness, is what it ended up being. However the king did not intend this. He informed the Germans that he intended to use the Romanian army as a “block” to allow them to peacefully retreat out of Romania before the Soviet army arrived. Germany refused this and instead tried to overthrow the new government and occupy Romania. Thereafter the die was cast, and Romania declared war on Germany and joined the Allies for the remainder of WWII.

A new communist government was installed by the Soviet army even before Germany had surrendered. Two years later, all political activity except the communist party was banned and the country became a dictatorship.

(Like many of the new communist nations in eastern Europe, early post-WWII Romania used captured or surrendered German equipment throughout the late 1940s, including this PzKpfw V Panther. Designated T-5, the last was retired in 1950.)

From 1947 – 1965, the leader was Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej. A typical hardline communist, the Romanian army was extensively re-equipped by the USSR during his time in power.

(The Soviets began supplying WWII T-34 tanks in the late 1940s. Here Romanian infantry in desant are armed with Mosin-Nagant 91/30s. Desant, or infantry riding the outside of tanks, is frowned upon in American tactics but was common in the USSR and Warsaw Pact.)

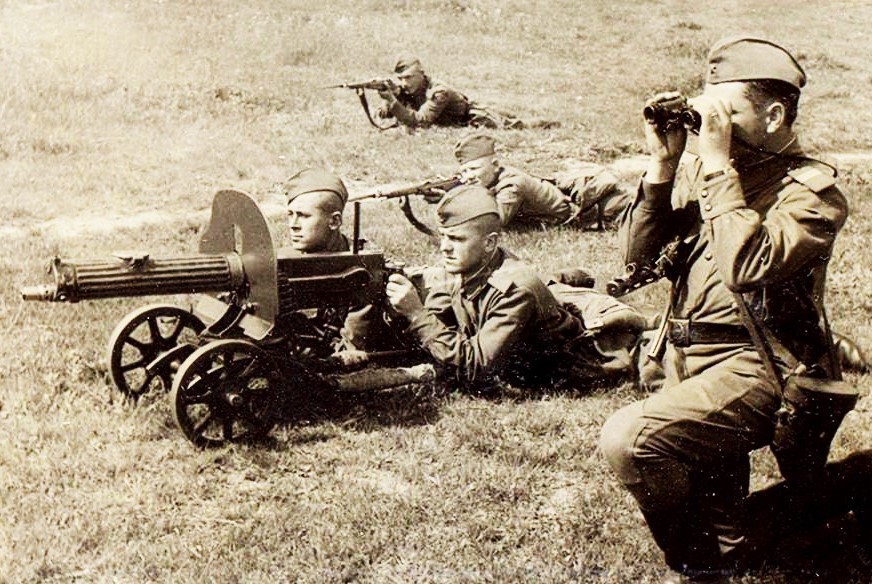

(Romanian infantry of the 1950s, armed with Mosin-Nagant M44 carbines and a M1910 water-cooled machine gun. Both weapons were WWII Soviet equipment supplied to Romania after WWII.)

(The USSR sold Romania Yak-23 “Flora” jets beginning in 1951 to replace WWII-era propeller fighters.)

(Along with the Mosin-Nagants, the Soviet Union provided Romania with huge quantities of leftover WWII PPSh-41 submachine guns. Romania considered making more themselves and a small batch was license-made under the Romanian designation “PM Md. 1952” before the project was halted. Postcards like this were made available to soldiers in December as a secular marxist alternative to sending Christmas cards.)

In 1965, Nicolae Ceausescu took over. Ceausescu remains a communist dictator difficult to characterize, and not for any good way. Until his ouster in 1989 he ruled Romania in a tyrannical and haphazard fashion.

(Nicolae Ceausescu in 1953, when he was still Gheorghiu-Dej’s defense chief.)

Ceausescu’s mismanagement of Romania was catastrophic. Arrogant but deeply paranoid – including of his own army – he was also (simply put) just a weird person. One hallmark of his disastrous quarter-century at Romania’s helm was a quest to “make a name for himself” in the communist world, by irritating and provoking the Soviet Union as often as possible, right up to the point where he could still get away with it.

Ceausescu excused the last Soviet troops stationed in Romania in 1967. In 1968, he refused to have Romanian forces participate in the joint invasion of Czechoslovakia, and in 1969 forbade Warsaw Pact troops (including the USSR) from even crossing Romania in transit. During the 1970s, more rules were invented, including a cap on the number of Warsaw Pact ships which could sail across Romanian waters at any one time. Also during the 1970s, an offer of military aid from China was accepted, which enraged the USSR. (Most of the Chinese equipment provided turned out to be low-quality.)

Ceausescu’s foolishness resulted in Romania sliding down the priority list for new Soviet-made firearms. As far as the Mosin-Nagant’s story goes, it did not really matter by then. In 1956, limited numbers of semi-auto SKS rifles already began to replace the WWII-era bolt action Mosin-Nagants in the regular army. During the 1960s, production of the PM Md. 63/65 (Romania’s AK-47 clone) began. By the 1970s the Mosin-Nagant was already gone from regular army use.

a voracious appetite

Before that happened, Romania had huge holdings of Mosin-Nagants which seemed to constantly increase during the 1940s and 1950s.

The foundation was Mosin-Nagants already in Romanian use when WWII started and those captured when the nation was still in the Axis. Next came big tranches of Soviet military aid after WWII. Still after this, Romania purchased ex-Soviet Mosin-Nagants from third countries (East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Yugoslavia) phasing them out; then, also purchased post-WWII production from Poland and Hungary when those too were phased out in their homelands. Finally Romania made its own as detailed later below.

This led to the Romanian army having a huge variety of Mosin-Nagant submodels, ages, origins, modifications, and manufacturers represented – maybe more so than in any other army in the world.

(A Hungarian M44 Mosin-Nagant carbine of post-WWII production which was later purchased by Romania.)

(This was a czarist-era Russian Mosin-Nagant M93 dragoon gun which Romania rebuilt into a 91/30 rifle.)

(A WWII-production Soviet M38 Mosin-Nagant short rifle which was transferred to Romania. It was later refurbished for continued Romanian use.)

(This was a Model 1891 long-rifle Mosin-Nagant originally made at Ishevsk in czarist Russia during 1915. After WWII Romania restocked it and repaired it with parts off a Setstroyesk-made rifle. Curiously it retained its original rear sight marked in arshins, a unit of measure that went extinct when the USSR switched to the metric system in 1925. 1 arshin = 2’4″ or 0.7112m.) (photo via 7.62x54r.net website)

(Romanian soldiers with WWII Soviet M44 carbine Mosin-Nagants during a 1955 parade. The trucks are ZiS-150s, a Soviet type common throughout the Warsaw Pact.)

Romanian refurbishments

Due to the huge quantity on hand and the rifle’s later service in the Gărzile Patriotice, it was beneficial for Romania to refurbish foreign-made Mosin-Nagants.

The most common repair was broken or rotting stocks. If at all possible, part of the existing furniture was retained via an intricate wood splice. Sometimes the whole thing was replaced. The new stocks used a species of beechwood native to Romania.

(This was originally a Mosin-Nagant M93 dragoon gun which Romania restocked and rebuilt into a 91/30 rifle. Here the dogtoothed wood splice can be seen by the difference between beech and walnut.)

Sometimes entire subassemblies like the internal magazine, trigger block, or sights were replaced. This might be done either via a cannibalization program or by entirely-new manufactured parts. If the latter route was chosen, the new item was stamped with a Romanian parts marking.

As far as markings overall, the Romanian experience varies widely. Other than the domestic production described below which is obviously uniquely marked; the country didn’t seem to care what markings were or were not on foreign-made Mosin-Nagants and often did not put much effort into changing them.

This was not universally true; for example some had cyrillic lettering or Russian / Soviet symbols filed off during WWII. Others have markings removed or added for no apparent reason.

(photo via 7.62x54r.net website)

Above is one end of the spectrum, completely unaltered. This Romanian Mosin-Nagant was formerly a WWII Soviet army 91/30 rifle, made at Izhevsk in 1939. It still has the USSR coat of arms. The faint circled marking (extreme lower left) is Soviet indicating the chamber was proof-tested during manufacture. The little diamond is the Soviet quality control stamp. The big diamond is most likely an accuracy proof-firing.

Above is the other extreme end, a Mosin-Nagant M93 dragoon gun which Romania restocked. It was made at Izhevsk in Russia in 1899 but pretty much everything else besides the serial number is crudely peened away. The “artist” had enough forethought to not obliterate the proof-test mark. This may have been a WWII battlefield capture.

ROMANIA’S PRODUCTION

To supplement its existing holdings, Romania opted to self-produce Mosin-Nagant M44 carbines after WWII.

(Romanian-made M44 Mosin-Nagant carbine.) (photo via Epic Auctions & Estate Sales)

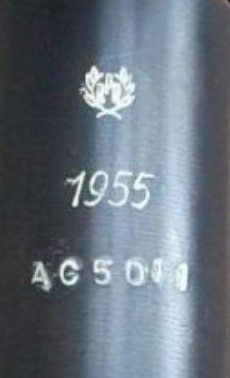

Romania manufactured the M44 carbine in a three-year span between 1953 – 1955. All were made by Cugir. The rifles were made in production lots of (more or less) 2,000 and denoted by a two-letter prefix to the serial number, which restarted with each lot.

(The 715th rifle of lot # “LE” in 1955, the final year of Romanian production. The arrowed delta is the Romanian maker’s mark. RPR is People’s Republic of Romania.) (photo via 7.62x54r.net website)

There is no rhyme or reason to the 34 production lots, they jumped around the alphabet. Perhaps this was intentional to obfuscate how many were being made. The total built was between 68,000 – 71,000 depending on the source quoted.

Romanian-made M44s are true to the WWII Soviet standard in most regards. One exception is the trigger, which is to a more refined design and has about half the pull of a WWII-made M44’s trigger. Another minor difference is that the groove in the furniture is more pronounced than in WWII-made M44s.

It does not appear that Cugir manufactured a spare parts run. Many Romanian-made M44s in private hands today have parts cannibalized off other Mosin-Nagants. Certainly this was done in the rifle’s service period, and it is not beyond belief that good-condition parts off unserviceable guns were already utilized at the factory when the new M44s were being manufactured.

There are a few interesting examples, functionally identical but more desirable to collectors today. The “AC” production lot of 1955 has markings of a much “cleaner” style, with the year in a different font.

The reason for this is not known.

Another oddity done in 1955 for unknown reasons was a small number manufactured with an alternative rear sight, with the numerals in a bolder face in the center of the sight’s blade as opposed to the edges.

There is no apparent benefit. It is not a “transitional” concept either, as this does not appear on the rear sights of the SKS or AK-47; the two rifles which replaced the Mosin-Nagant after WWII.

Romanian-made 91/30s

A rare Romanian type was a very small batch of 91/30 long rifles made in 1955. For certain no more than 999 were made and quite likely much fewer than that.

(Romanian-made Mosin-Nagant 91/30 rifle.) (photo via russian-mosin-nagant online forum)

These 91/30s are prefixed in the “AC” production lot of M44 carbines in 1953 and may have been interspersed with them. All have a serial number starting with “5” however 5,000 certainly were not manufactured; most have serials in a tight two-digits span of 50xx.

To further muddy the waters there was an even smaller number of 91/30s built in 1953 which have no production lot, and only a plain serial number, all known examples of which are in the two digits.

Why Romania made these is unknown. In manufacturing, there is neither a benefit nor detriment to making a long rifle vs a carbine. One theory is that there was a surplus of replacement 91/30 stocks for the refurbishment effort available, and Cugir used these to cut a corner on the M44 job.

suppressed variant

These were strictly-speaking not new, but extensively modernized existing Mosin-Nagants. They were issued in tiny numbers to an elite anti-terrorism unit of the Securitate, Romania’s secret police.

The optics was a modified Soviet PSO-1 4×24 scope which was nearly identical to the Romanian scope on the Cugir PSL-54, the built-for-the-purpose sniper rifle which then later replaced these guns.

All of these went to the Securitate. The actual army used the (unsilenced) sniper version of the Mosin-Nagant 91/30 with Soviet PU scope.

Romanian ammunition

Romania was self-sufficient in 7.62x54mm(R) throughout WWII and the entire Cold War era. Romanian-made ammo of this caliber was of high quality and generally considered the best-made in the whole Warsaw Pact including the USSR. It shipped in standard combloc sheet metal containers aka “spam cans”.

.

.

Going clockwise is the caliber with codes of the bullet (148 grain spitzer) and casing (berdan-primed brass) types, “Model of 1908” which was Romania’s internal nomenclature for this ammo, then on the second line that it was production lot #55 in 1975 by U.M. Sadu (factory code “22”, which also appears on each round’s headstamp). After the stripe, the can shows the rounds use Soviet-style VT powder, lot #54 of 1975. The final line shows 440rds and “without blade” meaning no stripper clips are included.

The stripe of colored paint is common to all Warsaw Pact spam cans and was intended that export recipients using, say, the Arabic or Korean alphabets, could immediately identify the contents. Here silverish-white denotes standard FMJ ball. Romania made a wide variety of 7.62x54mm(R) types including heavy ball (yellow stripe), AP-incendiary (red), tracer (green), and so on.

U.M. Sadu was the post-WWII reorganization of the old Royal Pyrotechnics Armory in Bumbesti-Jiu, and used factory code 22. Cugir in Transylvania used factory code 21. These two factories made the overwhelming majority of Romanian 7.62x54mm(R) ammunition.

“Exercitiu” & “Instructie”

These two markings appear today on surplused Mosin-Nagants of all types once used by Romania. Within the collector community there is significant debate as to what exactly they mean. The answer is surprisingly complex for something so mundane.

“Exercitiu” translates as “exercise”.

Within the communist-era Romanian military it was not a new firearm classification, appearing after WWII even prior to the creation of the Warsaw Pact.

(This 1953 photo shows Romanian soldiers with old Model 1891 long-rifle Mosin-Nagants, stamped EXERCITIU on the buttstock. Romanian infantry doctrine during the 1940s and 1950s was to carry a WWII Soviet-style greatcoat rolled up as shown in all seasons, as the garment doubled as a field blanket. The soldier on point has a WWII German MP-28.)

Exercitiu rifles were clearly marked as such, with the word carved into the buttstock and stamped or engraved atop the receiver.

(Exercitiu-stamped Mosin-Nagant M44 carbine. This particular one had been WWII Soviet production at Izhevsk.) (photo via 7.62x54r.net website)

They later had a black band painted on, or later still, the entire buttstock was painted jet black.

(Exercitiu Mosin-Nagant M44 carbine with all-black buttstock.) (photo via 7.62x54r.net website)

The meaning of Exercitiu changed over time. Originally it designated firearms which were restricted against standard issue to active-duty troops, but, still suitable in varying degrees for peacetime training.

During the Cold War this changed significantly, and “Exercitiu” came to mean a rifle specifically prohibited from being fired in any capacity. To this, the Mosin-Nagant’s firing pin was clipped off. Exercitiu Mosin-Nagants as a rule received no maintenance and frequently have other parts broken or missing, in addition to being in atrocious physical condition.

(Exercitiu-stamped receiver on a World War One-production Mosin-Nagant later restocked in Romania. This was originally an Imperial Russian weapon; the czarist eagle has been buffed out as seen.) (photo by Kevin Carney)

Obviously a rifle which doesn’t shoot is not of great use to any army, even in secondary roles. These beat-up weapons certainly would not see ceremonial use either. The Romanians still felt they had utility in niche uses such as classroom teaching, marching practice, or bulk handling drills for logistics units.

Today it is universally agreed that Exercitiu Mosin-Nagants should not be fired, even if refurbished. While the firing pin (or even the entire bolt) can be replaced, the rifle’s provenance is not known and there may be another underlying danger.

(An interesting Exercitiu example is this Mosin-Nagant made by New England Westinghouse in East Springfield, MA in the United States. During 1915 Czar Nicholas II placed an emergency order for long-rifle Mosin-Nagant 1891s to this American company. This one was later rebuilt into M44 carbine configuration, either in the USSR or Romania. The original American serial number was filed off and replaced at some point. An additional later stamping of some sort, added either in Soviet or Romanian service, was also obliterated (probably by the post-Cold War importer) after it had already been downgraded to Exercitiu status, as evidenced by part of the “Ex.” accidentally being buffed.)

Exercitiu-marked Mosin-Nagants are today uncommon. By 1989 their limited niche utility meant there were probably not many to begin with, and unshootable rifles held little resale potential for civilian import / export companies. Extant examples of these useless guns in the 2020s collectors market typically came in bulk shipments exported out of Romania in the 1990s, mixed in (accidentally or otherwise) by the Romanian seller in crates of normal Mosin-Nagants.

Less rare, but still not common, are ex-Romanian Instructies. “Instructie” translates to “instructional”.

In Cold War-era Romania the Instructie classification denoted an obsolete firearm unsuitable for general issue but desirable for continued training use.

(This Instructie carbine was one of the actual Romanian-made M44s from the 1950s.) (photo via 7.62x54r.net website)

Instructie guns always had a bright red stripe painted onto the buttstock; sometimes the metal cup of the butt was red also. The word was (usually) also carved or painted onto the wood furniture. Usually (but not always) this was on the buttstock.

(Instructie Mosin-Nagant 91/30 long rifle.) (photo by Kevin Carney)

The same was (as intended anyways) engraved or stamped atop the receiver.

(Pre-World War One Model 1891 long-rifle Mosin-Nagant with Cold War-era Romanian Instructie stamping.) (photo by Kevin Carney)

The engraving / stamping on the receiver is not universal and the Romanians either discontinued it to save money, or, just had poor quality control in this regard.

Instructie rifles were often functional and useful for basic training and other such duties. The Instructie project was not limited to Mosin-Nagants and other WWII firearms were involved.

(Romanian Instructie-marked vz24 rifle.)

Today there is debate as to the wisdom of firing an Instructie Mosin-Nagant. One school of thought is that if the firearm is in decent condition, inspected by a gunsmith, and used with normal-load ammunition, there is no problem. Another is that they should be grouped with Exercitiu rifles and not be fired. For those in agreement with the latter, a word of caution is that Instructie rifles may not be apparent as such.

(This is an ex-Romanian wz.44, the post-WWII Polish clone of the Mosin-Nagant M44. It was an Instructie carbine late in its Romanian career but not stamped / engraved on the receiver. Meanwhile the red stripe is totally worn away and an “Instructie” carving is only barely faint on the other side of the buttstock.) (photo via 7.62x54r.net website)

As mentioned earlier not all Instructie rifles received the mark atop the receiver. The red stripe was painted with whatever type of paint was handy over the furniture’s finish and often flaked off. The carving into the wood is sometimes so shallow that it can easily be sanded away.

Both Exercitiu and Instructie examples of Mosin-Nagants sometimes have a latin-alphabet “F” added to the manufacturing nation’s serial number.

(“F” suffix added to a czarist-era ex-Russian Mosin-Nagant in Cold War-era Romanian service.)

For some time this “F” was thought to signify somehow a rifle unfit for operational use, with the letter signifying Formatie; which in English loosely translates into training system or format. However that does now not appear to be true, as it has been seen on Mosin-Nagants not involved in the two programs. It does not mean rejected (respins in Romanian), refurbished (restaurăta), obsolete (învechit), reserve (rezervă), withdrawn (retras), foreign (străin), or anything else seeming to fit.

the Gărzile Patriotice (Patriotic Guards)

In August 1968 the USSR, Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria invaded Czechoslovakia to quash a moderate government there. As mentioned above, Nicolae Ceausescu declined to participate. The Warsaw Pact operation was massively unpopular in Romania and Ceausescu feared that even though he had kept Romania out of it, the public would direct their anti-Soviet anger towards him.

Later in 1968 Ceausescu tried to co-opt the rage to his benefit, by redirecting it into militant Romanian nationalism. The creation of the Gărzile Patriotice (Patriotic Guards) was announced. This was to be a “citizens militia” separate from the regular Romanian army.

Similar organizations already existed around the communist world including the KdA in East Germany, the Munkásõrség in Hungary, and the Worker-Peasant Red Guard in North Korea. Ceausescu (who fancied himself a tragically unappreciated military genius) sought to merge this concept with the “Total Defense Theory” used in countries like Vietnam, Singapore, and Yugoslavia.

There was nothing subtle about how Ceausescu rolled out the concept, he specifically stated it was to deter Romania’s allies from doing to it what they had done to Czechoslovakia.

Privately he also had a second goal. Mistrustful of his own military, he wanted a check on the regular army, in that the Gărzile Patriotice (who bypassed the defense ministry) might blunt any coup attempt.

The Gărzile Patriotice was organized into small cells of squad or platoon strength; each cell associated with a particular factory, collectivized farm, quarry, refinery, shipyard, etc. Civic works were included, for example fire stations and sewage plants had Gărzile Patriotice units. Larger industrial plants and towns had Gărzile Patriotice units of battalion strength. Each judet (county) of Romania also had an at-large Gărzile Patriotice battalion, as did the city of Bucharest.

Gărzile Patriotice units were issued very cheap uniforms with minimal insignia. A few units were issued old WWII-era M-1939 helmets but most received just a cloth hat as seen below. A gas mask was issued to keep to each member, and by the 1980s most every household in Romania had at least one. (In the first years after communism the gas mask bags were common children’s bookbags.) No combat boots were issued and Gărzile Patriotice members drilled in their civilian shoes.

(The Gărzile Patriotice unit of a government-owned mining company in the early 1970s, armed with WWII Mosin-Nagants.)

The total strength was 700,000 men and women, with a planned upper cap (never achieved) of 1 million. To provide a firearm for them would be a big undertaking in 1968 – 1969, and for this Romania’s huge stockpile of WWII Mosin-Nagants would be key.

(A Mosin-Nagant 91/30 which ended its Romanian career in the Gărzile Patriotice.) (photo via partisanrifles website)

Especially early on, up to the mid-1970s, Mosin-Nagants were by no means not the only obsolete firearm in Gărzile Patriotice use. Most anything from WWII onwards was acceptable.

(The Orita submachine gun of WWII was a well-made Romanian weapon. It fired 9mm Parabellum from a 32-round magazine. Several thousand were built during WWII. In 1948 – 1949 another batch was made. Oritas of both production runs were pulled from storage in 1968 – 1969 and reissued to Gărzile Patriotice units as seen above.)

(Romania’s WWII vz24 rifles were pulled from storage and reissued to Gărzile Patriotice units. There were some ex-German 98ks reissued as well. Romania still had a large stockpile of 7.92 Mauser ammunition in the 1970s and was actually still producing the caliber for export.)

(The vz30 light machine gun of WWII was reissued to Gărzile Patriotice units, here one is paired with a vz24 rifleman.)

During the 1970s the 7.92 Mauser-caliber weapons were slowly but surely replaced, with the Mosin-Nagant becoming the overwhelmingly most common type.

(Gărzile Patriotice during a 1970s winter drill with Mosin-Nagants.)

Despite being separate from the regular Romanian army, the Gărzile Patriotice sometimes held joint exercises with it. A tactics guide was promulgated and centered on local defense of the Gărzile Patriotice unit’s parent factory or town. Additional chapters dealt in how to repel an airborne assault, guerilla warfare, effects of a nuclear detonation, and the such.

(A soldier of the Romanian border patrol posing with a Guardsman’s Mosin-Nagant. This was probably in the late 1970s.)

At first, during the early to mid-1970s, the public was surprisingly receptive to this scheme. In part this was perhaps due to a law that paid their normal civilian wage while doing Gărzile Patriotice drills, plus free meals which in 1970s Romania was no small thing. University students received classroom credits for the drills. As time went on, the Gărzile Patriotice became just another drudgery and hardship Romanians had to put up with.

(WWII firearms were paired with newer combloc weapons in the Gărzile Patriotice. In the foreground is a RPG-7 (which Romania license-built as the AG-7) with Soviet PGO-7V optics kit. In the background is WWII weaponry, a M1910 machine gun and Mosin-Nagants. This photo likely dates to the late 1970s.)

final retirement of the Mosin-Nagant

By the mid-1970s, the Mosin-Nagant had become the sole Gărzile Patriotice longarm, now completely out of the regular army. At the same time it was clear that a WWII-era bolt-action rifle would be sorely outmatched by the FN FALs and M16s that NATO was using, and a replacement was needed. This would be the “Romy G”.

More properly the Puscă GP-75, this was an AK-47 with the action’s internal disconnector truncated preventing fully-automatic fire, even though they retained the full-auto sear. This was the results of complaints by the regular army of Gărzile Patriotice members “joyriding” standard PM Md. 63/65s initially issued and churning through large quantities of ammunition in full-auto.

These Romanian firearms were stamped G for the Gărzile Patriotice, hence the Romy G nickname outside of the country.

Romy Gs began to enter Gărzile Patriotice service around 1976. By the late 1980s they were the organization’s standard rifle but never fully replaced WWII Mosin-Nagants before communism ended.

(In Gărzile Patriotice service, the Romy G overlapped not only the Mosin-Nagant but other WWII firearms as well. Here in the late 1970s WWII German MG-34 machine guns were still in use.)

end of the Mosin-Nagant’s Romanian service

As mentioned the Gărzile Patriotice still had some Mosin-Nagants in the late 1980s. By then, that was the least worry of the Romanian military, or the nation overall.

In parades and international arms expos, the Romanian army showcased modern gear, in particular domestically-made arms including the TAB series of APCs, the MAT anti-tank mine, the A407 artillery piece, the DAC-665G pontoon bridging system, the Md.82 mortar, and so on.

(The TR-85 was a Romanian tank based on the USSR’s T-54/55 but with a laser rangefinder, new engine, and Romanian-made gun. The IAR-93 Vultur was an advanced strike jet developed jointly with Yugoslavia, which designated it J-22 Orao.)

Beneath the glitz the Romanian army had many very severe, deep-seated problems.

The Romanian army of the late 1980s numbered 140,000 of which 66% were single-tour draftees. The army had eight motor rifle divisions, two tank divisions, six mountain brigades, two artillery brigades, a rocket brigade with a few “Scud” ballistic missiles, and four airborne regiments. These were, on paper, all frontline active-duty formations.

However NATO estimated in 1989 that only two divisions (one motor rifle and one tank) were actually fit for battle. Six of the remaining seven motor rifle divisions were “deficient” either being only 50% manned or having obsolete kit (or both), while the last was rated “Arsenal category” being only 10% of authorized strength. One of the tank divisions was undermanned and still operating WWII T-34s in 1989.

Within divisions and brigades, the problem was worse still with subunits. The 1st Motor Rifle Division’s organic tank regiment was rounding out its numbers with WWII SU-100 tank destroyers. Two of the 9th Motor Rife Division’s regiments still had WWII ZiS-3 towed anti-tank guns in 1988.

The problems were not limited to the army. Behind the showcased MiG-23 “Flogger” fighters, the air force was still operating a unit of 1950s-vintage MiG-17 “Fresco” jets in 1989. Much of the navy was cheap Chinese-made patrol craft from Ceausescu’s friendship with the PRC. Both NATO and the Soviets considered these ships worthless.

There were 550,000 reservists (outside of the Gărzile Patriotice) but the call-up system was so backwards that mobilization would have taken a quarter-year.

Much of the military was diverted to civilian labor. These were not engineering units but rather combat soldiers; for example radarmen or tank drivers might be detached to harvest wheat, and helicopter mechanics and RPG gunners sent to repair highway potholes. This peaked in 1988 when 51% of the military was doing “side projects”.

While Romania’s army was not the smallest in the Warsaw Pact, it was the worst. In 1987 the Soviets considered it the least combat-effective of the eastern European puppets, with the most obsolete gear, worst training, and lowest political reliability.

Ceausescu wasted defense funds in other stupid ways. From 1978 – 1988 the “Danube Project” sought to develop an indigenous Romanian atomic arsenal outside of Soviet control. Both the KGB and CIA discovered this. The United States ended assistance to the civilian Triga research reactor. The USSR did not act; they (correctly) estimated that the project had no hope of success and the money wasted might make Romania more dependent on Soviet aid. Romania managed to enrich 36 lbs of uranium but was never even remotely close to a workable atomic bomb.

Ceausescu’s strange behaviors continued to irritate the USSR. The 1971 Warsaw Pact exercise “South-71”, of which Romania was specifically disinvited, is widely thought to have been a dress rehearsal for a 1972 invasion similar to the 1956 Hungary and 1968 Czechoslovakia operations; which in the end was not done. In 1978, during the Khmer Rouge’s genocide, Ceausescu made a state visit to Cambodia which even the Kremlin considered outrageous. By the late 1980s the KGB did not even think a coup or assassination of Ceausescu advisable. Romania had deteriorated so far that any disruption might simply result in the country becoming a “failed state” instead of a more reliable ally.

Romania had huge foreign debts by 1984 which Ceausescu tried to pay off with an austerity program. In 1987 the defense budget was cut by 11%, with a smaller second cut coming in 1988. The cuts had little overall benefit. Between 1978 – 1988 inflation ran 600% and both the civilian economy and military was under fuel rationing by 1987. Romania’s national electric grid had to be run at 100% just to meet minimal peacetime use and would have collapsed in wartime.

From 16 December – 20 December 1989, the city of Timisoara saw anti-Ceausescu rioting which took army tanks to contain. On 21 December, blue-collar workers from factories outside of the city were bussed in, presumably to rough up remaining protesters. Instead they turned on their handlers and joined the rebellion.

That same day in Bucharest, Ceausescu gave a now-famous speech which was interrupted by firecrackers on the crowd’s edges and sporadic hissing and boos. The state-controlled TV network cut away belatedly and it was clear to anybody watching that things were clearly wrong. As the crowd dispersed after the speech, many began to fight against security forces in the capital. By daybreak on 22 December 1989 (when Ceausescu and his equally-hated wife fled by helicopter from a rooftop) Bucharest was close to a war zone with tanks and APCs battling in the streets.

(Surprisingly some WWII weapons saw use inside Bucharest in December 1989. On the ground is a DP-28 machine gun, and the two men on the right have a Mosin-Nagant M44 and Mosin-Nagant 91/30.)

Ceausescu and his wife were apprehended on Christmas Day, given a drumhead trial, and executed.

During the initial troubles in Timisoara there was some attempt to activate local Gărzile Patriotice units however little thereafter. For one, things were moving so fast by 22 December that there was no time. Perhaps also, deep down Ceausescu realized that they were as apt to turn their Romy Gs and Mosin-Nagants on him as they were on the protesters.

(A man in Gărzile Patriotice uniform on 22 December 1989. Considering his jubilant mood, he probably wasn’t in the capital to help Ceausescu.) (photo via NBC News)

ex-Romanian Mosin-Nagants today

The army and police secured the Gărzile Patriotice’s warehoused guns during the last week of December 1989. A law of 5 January 1990 “Regulations To Keep Order” put the organization as a whole under the defense ministry, pending further reorganizations. It was never mentioned again and simply ceased to exist.

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, as the Romy G became prevalent, Romania had begun to scrap or sell off the Gărzile Patriotice’s Mosin-Nagants. Some later turned up as far away as Sierra Leone and Iraq. In 1989, there were still tens of thousands in storage, which the post-communism country immediately discarded through sale to the civilian market.

(An ex-Romanian Mosin-Nagant M44.)

Large quantities of ex-Romanian Mosin-Nagants were imported into the United States during the 1990s, primarily by Century Arms.

An ex-Romanian Mosin-Nagant manufactured outside the nation holds value neither above nor below one with a different backstory. Because Romania used Mosin-Nagants from such a wide variety of subtypes and origins, they are not really remarkable.

(Some ex-Romanian Mosin-Nagants have this marking, usually on the bolt handle knob. It is a pre-WWII acceptance mark of a foriegn-made rifle certified by Copsa-Mica Arsenal. Any ex-Romanian Mosin-Nagant which has this, made it through all of WWII and all of the communist era. It may or may not add a little to the rifle’s value today.)

The Romanian-manufactured M44s are somewhat more collectible and in 2022 typically fetch between $600 – $900. They are nowhere near as rare as post-WWII Albanian production, Estonian rebuilds, or Japanese Arisaka rechamberings, probably as common as Bulgarian 91/59s, and rarer than other iterations.

Romanian-made 91/30s are quite rare, very few are known to exist in private collections. In 2022 they easily price over $1,000.

I want to give a hat tip to the website 7.62x54r.net which is an incredibly useful research aid and overall just really interesting to read. -JWH (author)

LikeLike

good god. I used to see Mosins for $80. And people turn up their nose at that price.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know I remember $200 used to be considered outrageous.

LikeLike

Excellent Article and I own one of those Nagants , I bought in the 90’s. Very nice rifle.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic read, thank you. I just picked up a 1954 Romy M44 at a gun show. Overall in excellent shape with bluing wear on the buttplate and some shellac flaking and dents in the stock, but the rest of the rifle is top notch. Barrel is like new. This tells me it spent a lot of time being “drilled” with and very little being shot. Paid $600.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is still a really good price, I have seen them up in the $800s already.

LikeLike