I debated writing on this topic as it really doesn’t fit the theme of WWII weaponry being used after WWII. However in the past I have described how WWII warships were preserved, how they were modernized, and how they were transferred between countries. So maybe this will be of interest.

(The ex-USS Franklin (CV-13) being scrapped in 1966. This aircraft carrier had been terribly damaged in 1945, repaired at great expense, but never again used. Cut metal from other WWII warships fills the property of Portsmouth Salvage.)

(A Mk15 triple 8″ gun turret yanked off a WWII cruiser by Zidell during the 1970s. Zidell scrapped hundreds of WWII warships.)

(The ex-USS Sphinx (ARL-24), a WWII repair ship, being scrapped in 2007 by Bay Bridge Enterprises. The original shipbreaker for this job went bankrupt, which happened with increased frequency in the 1990s and 2000s.) (photo by Robert Hurst)

methods

drydock

Here the condemned WWII warship was put into drydock, then deconstructed from the top down. This method allowed 100% recovery of the ship and is also the “cleanest” method.

(Clemson and Porter class destroyers being scrapped in a Philadelphia drydock a year after WWII ended. These destroyers went obsolete even as WWII was ongoing. For the reasons outlined below, multiple warships were often simultaneously scrapped in the same drydock.) (photo from Warship Boneyards by Kit Bonner)

The problem is cost. Drydocks are limited in number and expensive to rent, especially for shipbreakers operating on already paper-thin profit margins. As they are also needed for cargo lines and navies to maintain active ships, they are often booked months in advance. This means the scrapper would have to sit on a ship bought at auction until then, increasing his exposure to metal prices dropping.

beaching

Here, a ship is intentionally run aground bow-first at the highest possible speed at high tide. The ship is then torched apart at low tide, chunk by chunk, with cut sections then dragged up the beach to allow the next chunk to be torched off. As the ship lightens forward, tractors pull it in more, until the stern is accessed.

(INS Vikrant was launched as HMS Hercules at the end of WWII but postwar Britain could not afford to complete it. It was purchased by India and completed to their specifications. INS Vikrant decommissioned in 1997. This November 2014 photo at Alang shows the beaching method, with the flight deck’s forward lip coming down.)

Other than being (by far) the cheapest method, beaching offers no other benefit. Obviously it is massively polluting as any liquids or debris on the ship go directly into the ocean. The beach ends up full of oil, smoking debris, and jagged pieces of metal. It is also time-intensive and only suitable for shipbreakers with low labor cost. Invariably some percentage of the ship is lost in the process. It is regarded as having the lowest worker safety of all methods.

Alang, India is famous (or infamous) for the beaching method. It is also used at Aliaga, Turkey and shipbreakers in Bangladesh and China. In the post-WWII United States, it only saw sparing use as other methods were more widely available.

basin

Essentially a more elegant version of the beaching method, here a narrow, very shallow slit (or “basin”) is dredged out of the shore. Often this is on a sheltered waterway with less storm hazard.

Tugs push the condemned WWII warship into the basin. Scrapping then takes place similar to the beaching method, except, cranes can travel the sides of the basin so it need not be strictly bow-first.

(The WWII aircraft carrier USS Cabot (CVL-28) being scrapped via the basin method in 2002.)

This is probably the most efficient method and was (and still is) very widely used in the USA to scrap WWII warships. Shipbreakers at Brownsville, TX use it almost exclusively. It is cheaper than drydocking or building a pier, pollution is controlled, there is no danger of the ship sinking once in the basin, and access is available on three sides of the hull.

(USS Paiute (ATF-159) was a WWII Abnaki class fleet tug. Decommissioned in 1992, it was scrapped in Virginia in 2003.) (photo by Alan Owen)

pierside / composite methods

This is essentially a combination of the above techniques. After WWII it was widely used, especially for large vessels like battleships. It was popular not only in the USA but in Europe, where it was the main method.

(This May 1949 photo at Inverkeithing, Scotland shows battleships HMS Rodney, HMS Revenge, and HMS Nelson. HMS Rodney is alongside a special scrapping quay. Of these three HMS Revenge was obsolete and HMS Rodney was in poor mechanical condition by the end of WWII. But sister ship HMS Nelson had just received an expensive major refit in 1944, and still had many years of possible service. Budget cuts forced its decommissioning in 1947 and scrapping two years later.)

Here the condemned WWII warship was first brought alongside a pier or quay equipped with heavy cranes. Pierside, the ship was scrapped top-down, first the superstructure and gun turrets, then the weather deck, then large internal items like turbines and reduction gearboxes.

(This was USS Orion (AS-18), a WWII submarine tender scrapped by North American Ship Recycling in 2006 – 2007. Here the hull rides high pierside with the superstructure and upper decks removed.)

As work proceeded downwards, the ship was ballasted either fore or aft to make either / or area near the waterline accessible. This alternated like a see-saw, with the ship becoming progressively lighter and draught continuing to decline.

(The WWII aircraft carrier USS Coral Sea (CV-43) being bow ballasted by the weight of remaining decks forward.)

At a certain point, what remained (called “the canoe” in the industry) was gingerly towed to either a basin or beached, as seen below.

(The “canoe” of the aforementioned USS Orion after being floated away from the scrapping pier. The yellow tackle block at lower left will be used to beach it.)

(Here the ex-USS Orion has been pulled aground.)

After this, scrapping resumes going fore-to-aft. As forward sections are eliminated, the pull cables are repositioned, and so on, until the underside of the stern is fully on dry land and the job ends.

For any method above that involved the condemned WWII warship being in the water during scrapping, care had to be taken to maintain lateral & longitudinal equilibrium. This accounts for the sometimes odd appearance of WWII warships mid-scrapping, with seemingly “earlier in the process” items still onboard, often to balance out weight.

(In this photo of the ex-USS West Virginia (BB-48), the WWII battleship’s superstructure and even part of the first deck is gone, yet stubs of the forward Mk5 16″ guns remain as does even part of the “B” turret’s armor face.)

what was in WWII ships

Of course steel was the overwhelmingly main metal. Shipbreakers scrapping WWII warships broke this down into categories.

Heavy melt steel, or HMS, is ¼” or thicker and cut into 2’x5′ pieces or thereabouts. This was most desirable. Certain premiums might be had for a HMS type called maraging (steel with elevated nickel content, such as the armor of WWII battleships and cruisers).

(WWII gun barrels made good HMS, being of exceptionally high-quality steel and often with elevated nickel and chromium content. Here two torched Mk5 barrels lay smoking on the deck of the ex-USS Colorado (BB-45) as it is scrapped in 1959.)

Number 2 was steel too thin or small to be HMS. Steel like this was found in a warship’s ventilation ducts, AA gunshields, stanchions, internal fixtures, lockers, and so on. In the early years after WWII, shipbreakers would cut this into manageable sizes, compress and bale it, and ship it to steel mills that way. Starting in the 1960s, shredders were developed that chewed steel into baseball-sized pieces and made it more desirable. It was then named “shreddable”, the term still used today.

Cast iron was found in anchors, motor housings, and so on.

Non-ferrous metals made up a tiny percentage of a WWII warship by weight, but were infinitely more valuable and shipbreakers often removed them as soon as possible. Brass was widely used in WWII, in all types of things when rust would otherwise be an issue. It was also widely used in magazines and gun turrets, as brass does not spark. Bronze was used for propellers. Stainless steel was used in galley equipment. Copper was the most valuable metal of all. It was mainly wiring, but also motor windings, transformers, and electric bus bars.

(The huge electric motor aboard USS Chinquapin (AN-17). This WWII netlayer was mothballed six months after WWII ended and was never reactivated, being scrapped in 1976.)

Breakage was impure metal or mixed metals. The shipbreaker had to decide if it was worthwhile to further process breakage or just sell it as-is.

Dunnage was the last category. It was simply byproduct of a scrapped WWII warship: wood, canvas, glass, bakelite (an early plastic), rope, firebrick, life vests, rubber, mineral wool, tar, and so on. Dunnage was worse than worthless to a shipbreaker, as he had to either incinerate it or pay somebody to truck it to a dump.

(The big WWII troopship USNS General Nelson M. Walker (T-AP-125) was scrapped by All Star Metals in Brownsville, TX in 2005. This material: fabric bunks, wood, upholstered furniture; is dunnage.)

different levels of scrapping

I: reselling the whole thing

Unless prohibited by the government, shipbreakers in the USA had an option of not scrapping the ship at all and trying to resell it intact. For some types, like a WWII seaplane tender, this was unlikely as there is no analogous civilian counterpart. But for many types – notably the WWII “Yard & District Craft” program types like lighters, tugboats, barges, dredges, ferries, and so on – they were good for resale, especially in the 1940s and 1950s when they were young. If no customers were forthcoming after a while, the ship could still be scrapped then anyways.

(The nameless YF-875 was a WWII Yard & District Craft program 133′ cargo lighter. It was mothballed after WWII and auctioned for scrap in 1974, however it was not scrapped and somehow ended up in Canada where it was still afloat in the late 2000s.) (photo by Bob Gerard)

Naturally the WWII Liberty and Victory Ships described later below were suitable (they were never warships to begin with). Certain discarded US Navy types, like oilers, stores ships, and rescue tugs were readily convertible. LSTs were also convertible.

(A 1971 ad from Zidell for three WWII tank landing ships. The USA built 1,052 big LSTs during WWII.)

(M/V Macoris was formerly LST-670. It decommissioned in 1946 and was “civilianized” in 1948. The 11½ kts LSTs were maybe not perfect merchant ships, but for limited budget cargo lines they were an option. Freight hatches were cut topside while the vehicle deck was subdivided into holds. The customer had the option of retaining the bow door or welding it shut. This ship had a serious fire off Brazil in 1953 and was scrapped.) (photo via navsource website)

Surprisingly, the Bogue class escort carriers (CVE) were designed from the start during WWII to be converted into merchants after peace came, if so desired. Otherwise they could be scrapped.

(HMS Ranee, the lend-leased USS Niantic (CVE-46) was rebuilt in 1946 – 1947 and served several cargo lines under different names, here S.S. Pacific Breeze. The ship was scrapped in Taiwan in 1974.)

II: saleables

(Power tooling aboard USS Vulcan (AR-5). This would be welcome in any civilian machine shop. This WWII repair ship was scrapped by Bay Bridge Enterprises in Virginia in 2006 – 2007.)

When the decision to scrap a WWII warship was made, not everything need be cut up. Scrappers could, and often did, resell subassemblies taken off intact for higher profits than scrapping them. The tradeoff was then the shipbreaker had to store the items until a buyer was found, and had to settle for less scrap steel tonnage in the meantime.

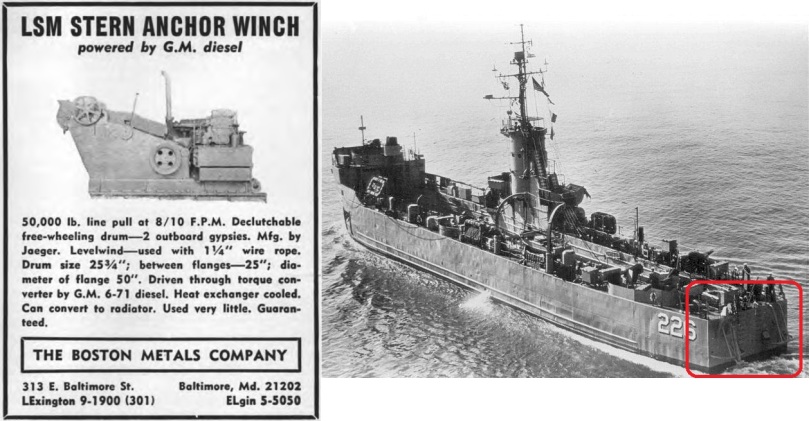

(1968 ad from Boston Metals, with an example WWII LSM shown.)

Above is one such item. On WWII medium landing ships, a pair of anchors designed to dig into the seafloor were dropped from the stern transom as the LSM approached the invasion beach, with the chains allowed to play out. When the amphibious assault was over, powerful diesel winches inside the ship (as seen in the ad) pulled in the anchors, creating a backforce which helped ease the LSM off the beach. These mighty winches had uses for a variety of industries.

(Late 1960s ad from Zidell)

It was uncommon but not unheard of for a ship to need a replacement anchor in its lifetime. More common was reselling anchors off scrapped WWII warships for use on new construction merchants. They were also sold to marine engineering companies to anchor things like work pontoons or floating piers.

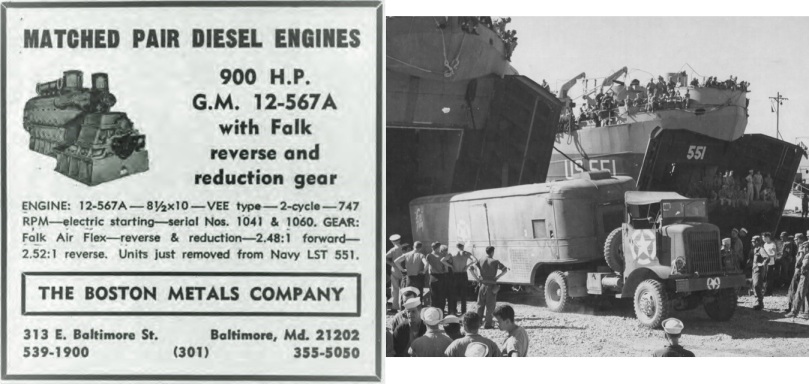

(November 1971 ad from Boston Metals and the ship mentioned, USS Chesterfield County (LST-551) in France during WWII.)

The General Motors 12-567A diesel engine was used on the WWII US Navy’s 180′ patrol ships, Achelous class repair ships, and the big LSTs. They were left/right “handed” to the port and starboard propeller shafts. To have a matching pair with the Falk gearboxes still attached was a strong reselling point. USS Chesterfield County (LST-551) fought in WWII and later the Vietnam War. Decommissioned in 1970, it was stripped in the United States with the hull towed to Japan for scrapping in 1971.

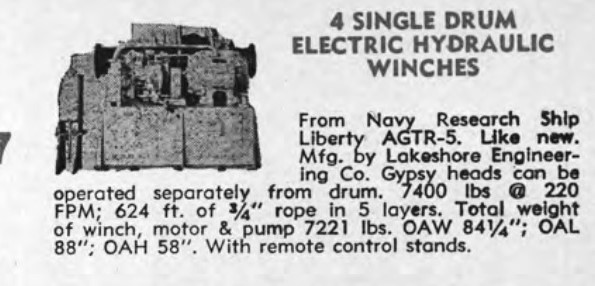

(1970s Boston Metals ad for a winch off USS Liberty.)

With saleables, shipbreakers only cared about the item’s value, not the history of the WWII warship it came off of. A pump off an obscure fuel barge sold just as well as one off a famous battleship. USS Liberty (AGTR-5) was a WWII Victory Ship hull rebuilt into an electronic surveillance ship in 1964. In 1967 USS Liberty was massively damaged by Israeli warships. It was scrapped by Boston Metals in Baltimore.

In the shipbreaking industry, saleables were a profit-maker from the 1940s through the early 1970s. Thereafter the market started to dry up. For one, the WWII equipment was by then three decades old. Specific to items intended for further at-sea use, insurance companies started to frown on the practice as well.

(Late 1960s ad from Zidell.)

By the 1980s, some insurance companies would not write policies on merchant ships with WWII-secondhand “integrity items” like watertight doors or firefighting pumps.

(1968 ad from Boston Metals for valves off WWII T2 tankers.)

The American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) is a private non-profit group which publishes industry standards that are more or less accepted as official in the USA. As decades passed, standards were updated, and sometimes saleables stripped off WWII ships needed alteration to stay eligible, or sometimes just became worthless altogether.

III: full scrapping

As decades went on after WWII, this was more and more common. Instead of first picking through the condemned WWII warship for saleables, it was all cut up as fast as possible. Turn-around payback speed on the purchase cost was now more of the essence than spending time to carefully extract saleables, which might never sell anyways.

Sometimes the shipbreaker’s decision was made for him. Below is the 2011 contract for the ex-USS Bolster (ARS-38), a WWII salvage ship.

The contract is specifically worded that the whole ship, and everything in it, must be scrapped.

selling agencies

The WWII Liberty, Victory, and T2 merchant ships all belonged to the War Shipping Administration. This body continued to function for one year after WWII ended. It was then abolished and rolled into the Maritime Administration.

The War Assets Administration (WAA) was created in 1946 by President Truman to streamline efforts of various agencies: the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (a repurposed New Deal-era governmental body); the Surplus Board; and others. WAA sold off gear of all sorts from all branches of the military, not just the US Navy.

(WAA employees Carl Fatzer and Louise Lobb open a January 1947 WAA auction. The goods in question were $350,000 worth of WWII US Navy engines.)

(A 1947 WAA ad for surplus WWII medium landing ships. The price equates to $464,500 in 2020 dollars. LSMs made less attractive merchants than LSTs as they had limited cargo space and rode waves badly in the open ocean.)

LSMs were one of the types WAA disposed of “as-is, where-is” after WWII. Buyers could buy them for merchant conversion, or speculatively in hopes of reselling them, or as scrap. The government honestly didn’t care what buyers did with them. The particular ship in the ad, LSM-328, had brought men ashore at Okinawa in 1945. It was bought by the Basalt Rock Company in California for scrapping in 1948.

As far as nautical goods, WAA was not just ships and shipboard equipment. It also dealt ashore kit like staff cars and pier cranes. Grounded naval warplanes were also sold as scrap.

(The SB2A Buccaneer was the worst US Navy airplane of WWII. Even before the war’s end they were throwaways, used only until they needed maintenance and then immediately discarded. This one was at a WAA sale in Georgia in 1946. The X on the tail signals air traffic control towers not to clear it for takeoff.)

WAA also sold off the government’s wartime equity stakes in commercial shipyards. In the extreme, whole buildings and even entire abandoned naval air stations could be bought.

WAA was abolished in June 1949. Thereafter, and up to the present, WWII ships to be scrapped were sold either by the US Navy itself or by the Maritime Administration.

DRMS

The Defense Reutilization & Marketing Service was the conduit for the US Navy to directly sell unwanted WWII warships after the war. The first step was to naturally decommission the ship, then “strike it” or fully remove it from the rolls, both active and reserve. From there, the title passed either to MARAD (described below) or DRMS.

DRMS sold American WWII warships of all natures but primarily combatants like battleships, submarines, cruisers, aircraft carriers, and destroyers. These could physically be at a NISMF (Naval Inactive Ship Maintenance Facility) mothball yard or at an anchorage shared with MARAD.

MARAD

The United States Maritime Administration, or MARAD, is a large organization with many responsibilities. After WWII one of them was taking care of the huge mothballed fleet of wartime merchant ships: the Liberty Ships, Victory Ships, and T2 tankers.

The 2,710 famous Liberty Ships were designated EC2-S-C1. In any variant they were usually called “C2″s for shorthand. The WWII cost was $1.99 million ($35.1 million in 2020 dollars).

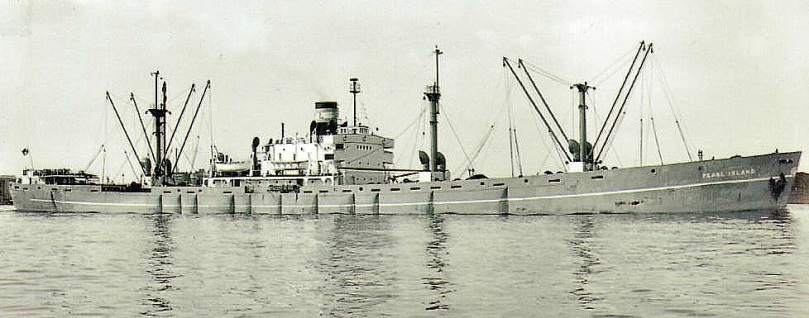

(S.S. Pearl Island had been S.S. John S. Casement during WWII. After the war it sailed under various owners and names. This Liberty Ship was scrapped in Taiwan in 1967.)

Liberty Ships, despite their crucial importance during WWII, were actually somewhat lousy merchants. They were only designed to be built as fast as possible, to swamp Germany’s u-boat effort by coming off slipways faster than they could be sunk. They had a crude steam reciprocating engine and a top speed of only 11½ kts. They were made of commercial-grade steel and had serious problems with hull cracking. (It probably didn’t help that they were often overloaded during WWII.) The design lifespan was only 60 months.

More than 2,400 survived WWII. Of these, many were immediately sold off to civilian operators with 835 retained by MARAD, initially at least, as a reserve asset to form convoys in any future war. During the 1960s and 1970s they were sent to scrapping and the last stragglers to go left in the early 1980s, by which time only one was still realistically capable of reactivation.

MARAD spent a lot of money tending to the mothballed Liberty Ships, but also made decent coin selling them for scrap. For shipbreakers, they turned into a gold mine. Merchant operators snapped them up for pennies on the dollar in the 1940s and sailed them far longer than their 60 month intended lifespan, in some cases for decades.

While they were still plying the seas, these Liberty Ships needed spare parts, which almost always came as saleables taken off other Liberty Ships already scrapped.

In commercial service Liberty Ships eventually fell victim to the worldwide change away from breakbulk freighting towards the 40′ container method. Starting in the 1970s, the remaining ones in use were no longer profitable to run. This partially coincided with the mid-1970s steel price surge and shipbreakers lucky enough to capitalize made a lot of money.

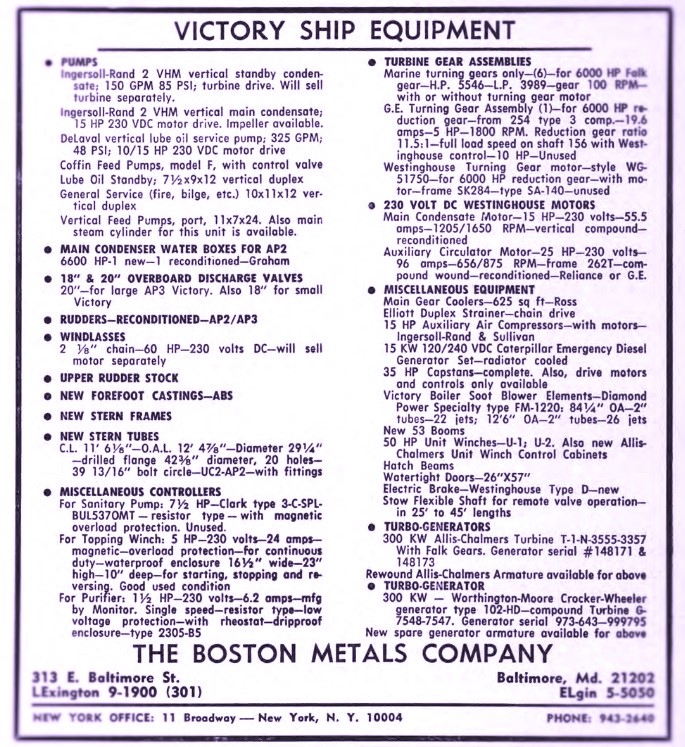

The WWII successor to the Liberty Ships (which nonetheless continued in production until V-J Day) was the Victory Ship, of which 534 were built at an average cost of $2.5 million each ($36 million in 2020 dollars). The were bigger, faster (15 kts) and more suitable to post-WWII use, either government or commercial.

(S.S. Biddeford Victory served various commercial owners after WWII. It was scrapped in 1976.)

(Late 1960s ad for Victory Ship parts. Near Boston Metals NYC field office was the Hudson Group, a nest of mothballed WWII Liberty Ships which was parceled off as scrap in the 1970s.)

Besides commercial use Victory Ships also remained in MARAD’s ready reserve fleets, awaiting the next war and slowly deteriorating. The last notable military use of a WWII Victory Ship was in 1985 when S.S. Hattiesburg Victory transported a US Army unit to Honduras for training.

During operation “Desert Shield”, the USA urgently needed sealift capacity. Only one of the remaining MARAD ready reserve WWII Victorys, S.S. Manderson Victory, was still in shape enough to even be considered. An evaluation team found it in poor condition, including a note “Painted July 1979”. While cosmetics were not a determining factor of the 1990 – 1991 sealift, that probably didn’t impress the team much. The reactivation was rejected.

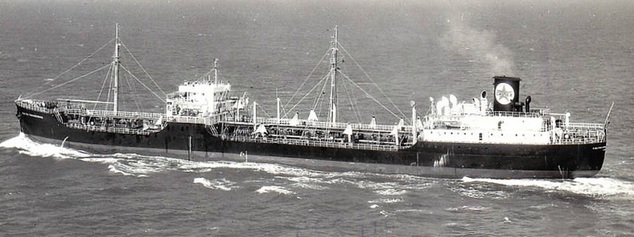

The final major WWII merchant type was the T2 tanker, basically a liquid cousin of the solid cargo Liberty Ship. Hundreds in various mods were built during WWII.

(This T2 was S.S. Carlsbad during WWII. After the war it was sold to civilian owners, shown here as M/T Caltex Johannesburg. It was scrapped in Taiwan in 1974.)

Surplus T2s remained in civilian service for decades after WWII, and much like the Liberty and Victory ships, were a hungry consumer for saleables taken off sisters already broken up by scrappers.

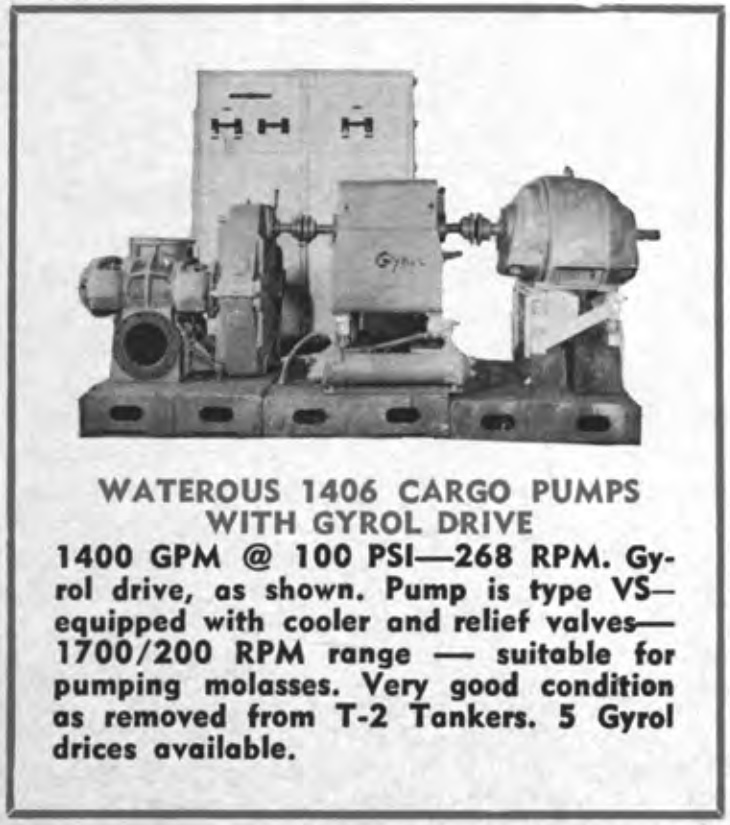

(1968 Boston Metals ad for a pump taken off a WWII T2 tanker.)

By the early 1980s the gig was largely up and the few Libertys, Victorys, and T2s still in commerce were sold as scrap.

Besides the merchant types of WWII, MARAD also handled warships. In the late 1940s any US Navy auxiliary and some small (less than 1,500t) surface combatants were auctioned off for scrap by MARAD.

Over the decades, additional WWII-built warships were acquired and sold via US Navy title transfer. Here, the US Navy periodically (every 3 years) considered if inactive warships still had any realistic possibility of future use. If not, the title was transferred to the Maritime Administration for Category X (minimal upkeep) layup and eventual scrap sale.

(photo via Panama Canal webcam)

As an example the above ex-USS General John Pope (AP-110) was a WWII troopship last used during the Vietnam War. Decommissioned in 1970, the US Navy transferred the title to MARAD. Already by 1990 this ship was stripped of parts and rusted, and not considered for Desert Shield reactivation. In 2010 a willing scrapper was finally found and this veteran of WWII, Korea, and Vietnam was “deadstick towed” from California to Texas via the Panama Canal.

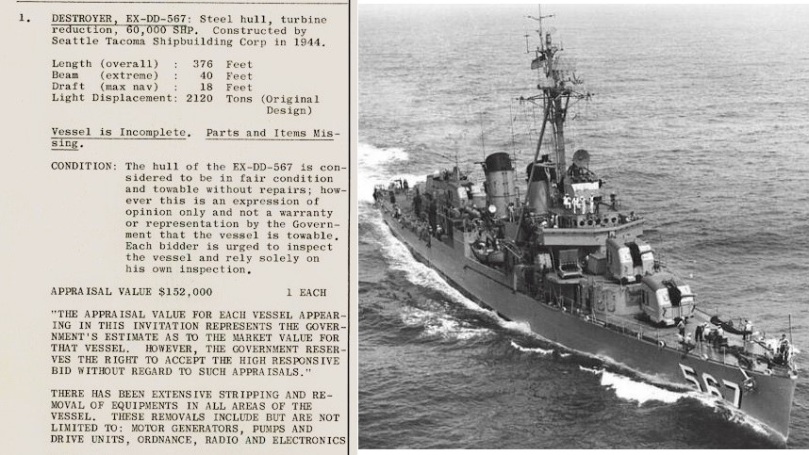

For either DRMS or MARAD the process was similar: the ship was appraised (described later below), an invitation for bids along with a description of the ship was published, and a winner emerged at auction. Auctions could be reserved, meaning that if a confidential minimum was not achieved the government voided all bids, or unreserved meaning the highest bid won no matter what.

Above is a snippet from a 1974 bid solicitation for the ex-USS Watts (DD-567), a WWII Fletcher class destroyer decommissioned in 1964. A general description is followed by a warning that the ship has been stripped of equipment, a summary of the hulk’s condition and suitability for towing, the appraised value, indication that it was a 1-ship auction, and legal disclaimers. This destroyer was scrapped by General Metals in Tacoma, WA.

The contracts grew more intricate as decades passed after WWII. By the 1990s, they were basically legal booklets.

(photo via navsource website)

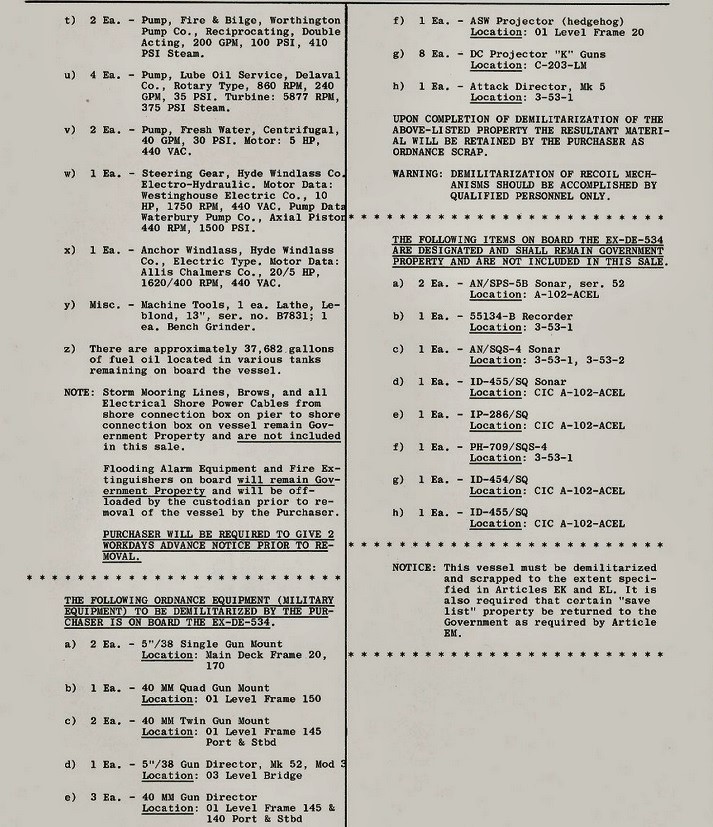

Above is just one page from the 1973 pro forma contract of the ex-USS Silverstein (DE-534). Decommissioned in 1959, this WWII escort ship was scrapped by Levin Metals in California in 1974.

This page lists certain saleables guaranteed to still be aboard, a warning that fuel is still aboard, and certain GFE (government-furnished equipment) notes. To this, some items including the mothball fleet’s alarms and fire extinguishers, still aboard during bidding would be removed after the auction. Others including the sonar system, mooring lines, and pier electricity connections, would be removed by Levin at their expense but then returned intact to the government without compensation. Remaining WWII weapons: Mk12 5″ main guns, Mk2 and Mk4 40mm AA guns, Mk51 off-mount AA gunsights, Mk11 Hedgehog, Mk6 K-guns, and Mk5 anti-submarine fire controller; all had to be certified as demilitarized by Levin. The ship itself had to be scrapped and not converted to civilian use.

Regarding fuel aboard, immediately (1946 – 1948) after WWII, mothballed warships were completely defueled. As years went on this wasn’t always accomplished. In Texas a cottage industry at refineries developed, where stagnant US Navy fuel recovered during shipbreaking was re-refined to usability and resold. Abroad, it often ended up in the ocean.

how ships were priced

When the USA sold WWII warships to allied navies for continued use after the war, the price was either a flat percentage of the WWII construction cost, or a set formula (“fair value cost”) of WWII price plus postwar upgrades less wear & tear. Either way there wasn’t much creativity. This was not true when appraising a ship for scrap.

The Defense Reutilization & Marketing Service used a more complex formula: the ship’s “LWT” (lightweight; which is not the same as displacement), the “index” (monthly steel prices in Pittsburgh), and the “factor” for type of warship, of which there were six. There was subjectivity. For example scrappers often complained that the LWT was wrong. The six type “factors” were vague, and in 1984 the US Navy was unable to provide a government auditor with any rigid criteria.

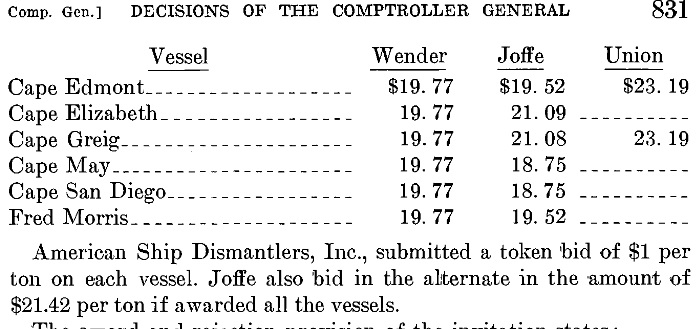

MARAD generally used a similar system for appraising a scrap price, but with even more nuances. Sometimes bids were sought on a per-ton basis for multiple types. These also could be priced a’la carte or for the whole lot. If a ship had a lot of intact saleables like winches, pumps, generators, etc then that could be factored in as well. Finally MARAD’s pricing could vary on how urgently they wanted to get rid of a ship.

(Example of a 1974 MARAD per-ton auction. The “Cape” vessels were all WWII C1s, a small freighter less famous than the Liberty Ships.)

In the UK, post-WWII shipbreaking happened in a much more compressed timeline. The peak came in 1949 when 580,000 tons of steel were recovered from WWII warships. One reason was that in 1945, the Royal Navy was less apt for future modernization than the US Navy. Ships like Flower class escorts, of which 261 survived WWII, had a top speed of just 16 kts and were not amenable to postwar tactics. They had been designed to fight at late-1930s technology level.

(The ex-HMS Duke Of York being scrapped in 1958. It was made flagship of the Home Fleet when WWII ended and served until April 1949. Britain initially planned to keep the four surviving King George V class battleships in service alongside HMS Vanguard; then still under construction. All four K.G.V.s decommissioned 5½ years or less after WWII ended, none was ever reactivated, and the ex-HMS Duke Of York was the last to be scrapped.)

Another factor was money. Great Britain was heavily in debt when WWII ended and whatever proceeds came from warship scrapping revenue was only a drop in the bucket by then anyways. It was considered more advantageous to generate immediate commerce and employment, and to that end, the UK sold WWII warships to shipbreaking yards at very affordable prices.

In the Soviet Union, appraising WWII warships to be scrapped was irrelevant as everything….the warship, the shipbreaking yard, the yard’s employee wages, their tools, the steel created by the event, and the electricity used; was all national property anyways. Putting aside political opinions, this might actually seem to be more streamlined than the American or British models. But it was not.

(The WWII cruiser Kirov is less famous than the 1980s atomic-powered namesake. Kirov decommissioned in 1974 and was scrapped in 1976 – 1977.)

Because warship scrapping is such a unique thing, it overlapped several parts of the Soviet system. The ship was delivered still in custody of VMF, the Soviet naval establishment. The disassembly part of the job, along with labor costs and the location itself, came under Minsudprom, the national shipyard directorate. Metal recovered belonged to the Steel Ministry. All needed support from SZhD, the USSR’s national railroad. Often there was two- or three-way bickering delaying scrappings. Since no profit was involved, there was little incentive to wring maximum value out of old WWII ships. All this meant that the Soviet effort was less successful than that of the USA or Great Britain.

where the money went

For WWII warships disposed of by the War Assets Administration shortly after WWII and later, by the Defense Reutilization & Marketing Service; proceeds from scrap sales went to either the Defense Department or to the US Treasury.

For MARAD sales, proceeds from selling WWII ships to scrapyards go to a fund called VORF (Vessel Operations Revolving Fund). The VORF is subdivided to 50% for upkeep of remaining mothballed ships, 25% to American merchant marine schools, and the remaining 25% to various other uses.

In recent years (2010 and 2017 being particularly bad), the VORF has been battered by the need to still pay expenses with little or no revenue coming in.

major players

Dozens and dozens of shipbreakers, big and small, came and went after WWII and it is impossible to list them all here.

Boston Metals in Baltimore was a prolific shipbreaker for decades after WWII. It had yards, both owned and leased, around the east coast. The C1-MAV-1 was a War Shipping Administration diesel-powered merchant of which 215 were built during WWII. This ad ran in a 1968 issue of Maritime Reporter magazine. By then, some WWII-era merchants could no longer get US Coast Guard safety certificates and S.S. Coastal Spartan was offered as a moored storage barge. This was not uncommon, and if no buyer came forward Boston Metals just scrapped it altogether.

Joffe was a smaller operation on the west coast. It too scrapped a good number of WWII ships. Despite the swanky business address, actual work was done in San Pedro or South San Francisco. This 1960s ad was for engine parts off T2 tankers it scrapped.

If there was a “king”, it was Zidell.

(The 38D8 diesel featured in this 1978 Zidell ad came off of scrapped WWII submarines, amphibious ships, and subchasers.)

Zidell Explorations of Portland, OR was started several months after WWII ended. It was highly successful in scrapping the earliest postwar discards, and in 1948 also spun off Zidell Valve, an early specialist company of saleables taken off WWII ships.

(USS Salamaua (CVE-96) decommissioned in 1946 and was scrapped by Zidell. During WWII this carrier had been hit by a kamikaze. Here, a paddlewheeler is pushing it into Zidell’s Portland yard.)

(The company owned Zidell’s Delight, a gutted WWII Liberty Ship hull turned into floating mount for a giant Whirley crane.)

Zidell was a well-run company, and scrapped 336 medium or large ships, and additional smaller or minor types.

(The WWII cruiser USS Baltimore (CA-68) being scrapped by Zidell in 1972.)

scrapping WWII ships in Brownsville

Brownsville, TX sits at the very southern tip of Texas on the start of the USA-Mexico border.

From the 1960s onwards, Brownsville has been synonymous with scrapping WWII warships. It has a dredged channel leading to breaking basins, and is just down the coast from MARAD’s Beaumont, TX anchorage and the US Navy’s former mothball site at Orange, TX. An in-house railroad, the Brownsville & Rio Grande RR, links shipbreakers directly into the American and Mexican national rail networks.

(The ex-USS Donner (LSD-20) being scrapped at Brownsville in 2005. This Casa Grande class WWII amphibious ship decommissioned in 1970.)

Another reason cited informally during the 1970s was that EPA and OSHA offices were in Dallas and Houston, and officials loathed the drive to the border and were apt to do inspections over the telephone.

Many shipbreakers in Brownsville have come and gone over the decades including Andy International and Esco. Some companies are the second or third occupants of lots owned by bankrupt operations of the past.

As the era of scrapping WWII warships ends, today the major companies are All Star Metals, SteelCoast, and International Shipbreaking Limited. These are by now highly-efficient and professionally-run companies, and the “wild west” days of Brownsville are gone, as are most warships of the WWII era.

scrapping American WWII ships abroad

After WWII “hot spots” for warship scrapping moved around, seeking lower labor costs, less regulation, high local demand for metal, and low taxation. Right after WWII Hong Kong and (surprisingly) occupied Japan were active. Later Spain, Italy, and Taiwan; then later still India; and then now today – with the WWII generation of ships gone – China and Bangladesh.

Early after WWII, American warships tended to stay stateside. The reason was not patriotism but financial: the economy was booming, decommissioned warships were plenty, demobilizing GIs wanted jobs, and regulation was lax.

As years went on, spreads between cost and profit tightened at American shipbreaking yards. The government was only interested in dollars, and ex-US Navy vessels of WWII began to be dismantled abroad where margins were bigger and shipbreakers bid higher.

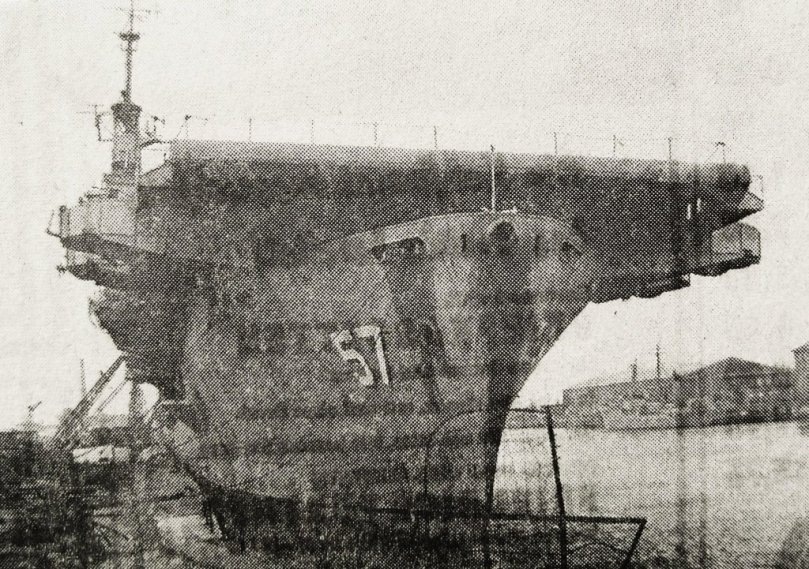

(The ex-USS Anzio (CVE-57), a veteran of the Bonins and Okinawa, was sold to Master Metals in 1959 who subcontracted a West German shipbreaker to do the work. Here the carrier is at Bremerhaven as cutting begins.)

The circus at Alang, India involving the ex-USS Bennington (described later below) led to a 1998 moratorium on the USA exporting decommissioned WWII warships to Asia. This did not solve the base problem, in that by the turn of the millennium shipbreaking was so unprofitable in the USA that many bid invitations went completely unanswered and unwanted old warships were starting to backlog.

(The ex-USS Orion (AS-18) was shopped around in the early 2000s but the government could not find any interested American shipbreaker, even at an asking price of $1. Barred from sending the WWII submarine tender abroad, MARAD paid an American company $734,230 to dismantle it. It was worse than giving it away for free.)

In 2003, MARAD thought it had a solution in Able UK, a shipbreaker in Great Britain which would scrap old US Navy warships in a manner safer and cleaner than in Asia but cheaper than the USA.

(The ex-USS Caloosahatchee (AO-98), scrapped by Able UK in 2009, was an oiler built during WWII but commissioned six weeks after Japan’s surrender. It decommissioned in 1990 and had asbestos, lead paint, PCBs, and hydrocarbon residue.) (photo by Jonathan Hare)

This turned into a debacle. The first four hulks, two of them WWII oilers, arrived in late 2003. Tabloids in London went hysterical and labeled them “toxic death ships”. Endless lawsuits meant that they were not actually dismantled until 2009 – 2010.

With the “dirtiest” ships of WWII generation largely gone, MARAD relaxed the moratorium in 2012 and again opened bidding to Alang shipbreakers. In fairness, India had started to crack down on the worse excesses there by then.

scrapping of WWII ships in Taiwan

Taiwan has a special niche in the story. After WWII the US Navy assisted rebuilding the nationalist navy (ROCN) to support it during the Chinese Civil War. After fleeing the mainland for Taiwan, the ROCN became a virtual “American echo”, from top to bottom ex-US Navy WWII ships.

Slowly but surely, these ex-US Navy WWII-era ships left ROCN service and needed to be scrapped. This industry was self-supporting. Besides the normal benefits, parts taken off scrapped WWII American warships could be resold to the Taiwanese defense establishment to keep other WWII-vintage vessels still in commission running longer.

(ROCS Te Yang, which served Taiwan from 1977 – 2005, had been USS Sarsfield (DD-837) during WWII. This massively-modified and upgraded Gearing class destroyer was aided by spare parts being taken off other American-built WWII Sumner, Fletcher, and Gearing class destroyers scrapped in Taiwan.)

Taiwanese shipbreaking was concentrated in the port of Kaohsiung, including two of the largest, Chi Shun Hwa Steel and Kai Sheng Steel Enterprise. The industry was aided by a hungry steel appetite from Taiwanese factories, low labor costs, and a cooperative government.

As the industry grew, it not only scrapped WWII warships of the ROCN, but then sister ships of WWII American types in ROCN service and still later; American WWII warship classes which Taiwan never operated at all.

(USS Sabine (AO-25) fought in the Saipan, Eastern Solomons, and Leyte Gulf battles of WWII and afterwards participated in the Cuban Missile Crisis.)

USS Sabine is an example. The Taiwanese navy never operated this ship nor any sister ships, but none the less the WWII oiler was sold to a Taiwanese scrapper in 1983 simply for the best price.

The biggest example of the this was the ex-USS Shangri-La (CV-38). This WWII aircraft carrier decommissioned in 1971 and had a request for reactivation in the early 1980s denied by Congress. In 1985, a “domestic only” scrap auction failed. In 1988, the clause was cancelled and the aircraft carrier was sold to Lung Ching Steel in Kaohsiung. In contrast to the ex-USS Bennington debacle in India described later, the Taiwanese scrapping of this WWII flattop went on with no problems in 1989.

(The quarterdeck bell – not the main ship’s bell – of USS Shangri-La. Middle school principal Lin Yaolong in Kaohsiung now owns it and uses it at his school.) (photo by Zhou Zhaoping)

One curious incident was USS Comstock (LSD-19), a big Casa Grande class amphibious assault ship commissioned during WWII.

In 1984, the ROCN was looking to replace ROCS Chung Chen, the former USS White Marsh (LSD-8), a WWII Ashland class amphibious ship. At the same time, MARAD was disposing of the ex-USS Comstock which decommissioned in 1970. Sold commercially to a Kaohsiung shipbreaker, the ex-USS Comstock was inspected by Taiwanese officers prior to scrapping starting, and found to be in good condition. It was decided to just keep the ex-USS Comstock, and it commissioned as the “new” ROCS Chung Chen with the “old” one scrapped in its place.

No “reuse prohibited” clause was in the contract, as nobody ever thought this would happen. For its part, the United States probably wasn’t bothered. MARAD got paid either way. The Pentagon couldn’t care less what happened to the obsolete WWII ship.

Taiwan had no blueprints or tech manuals for the Casa Grande class but by pooling the combined knowledge of other WWII American types in ROCN use, the “new” ROCS Chung Chen was not only serviceable but highly successful. It was later upgraded with RIM-72 surface-to-air missiles. If not for the propeller shafts becoming misaligned in 2012, it might still be in service today.

In a final irony, the WWII veteran escaped the scrapyard a second time. Taiwan scuttled the ship as a reef in 2015.

One shady aspect of Taiwan’s WWII warship dismantling was where some of the parts ended up. Nine regional countries had ex-American WWII vessels in their navy between the 1950s – 1990s, and in cases like South Korea, they were practically the whole fleet for a while. Some of these countries – Myanmar and Indonesia in particular – periodically fell in & out of favor with the USA but still needed spare parts. These were not “flashy” things like guns or radars, but rather items like piston seals, heat exchangers, gears, and so on. It’s known that at least once, parts of WWII warships scrapped in Taiwan ended up in Indonesian WWII-era US Navy warships via a web of resales by Taiwanese trade companies. It may have happened more often. When Saigon fell in 1975, communist Vietnam inherited intact a flotilla of ex-American WWII warships from the defunct South Vietnamese navy. It is suspected, but has never been proven, that Vietnam got black market American WWII warship parts from Taiwanese companies to keep them going.

Taiwan’s industry had a similar decline to the USA’s. By the 1980s labor costs and taxes had increased, and environmental laws were enacted. As the number of cheap WWII hulks still around declined, a reprieve came from scrapping supertankers damaged in the Iran-Iraq War but this was only temporary. The end came in late 1988, when Kaohsiung’s port authority evicted most of the shipbreaking yards to clear space for a new container terminal.

what could possibly go wrong?

For starters, the ship could sink.

HMCS St. Francis of WWII had been USS Bancroft (DD-256) during WWI. In 1940 President Roosevelt named it as one of his fifty “Destroyers For Bases” ships. This Clemson class destroyer was discarded by Canada in 1945 and sold to Boston Metals. Under tow, a passing merchant rammed and sank it.

(photo by Mike Green)

In 1973 the ex-USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) almost suffered the same fate. Under tow to Zidell’s shipbreaking yard, a passing ship collided with the WWII carrier’s starboard bow.

Asbestos is a silicate rock which can be woven into cloth. Its fireproof qualities have been known for centuries. It had other traits which made it attractive for use aboard warships.

Asbestos is a vibration dampener, which was useful inside WWII steel hulls with big guns booming topside. It is electrically non-conductive. It is a temperature insulator. It is a sound-deadener. Asbestos is strong, lightweight, and does not rust. It was cheap and could be installed by unskilled shipyard labor.

As seen above, the main WWII application was called lagging. Lagging was put around steam lines, pipes, hot exhausts, and ducts. It was put on boiler components, and lined the inside of WWII submarine pressure hulls. Lagging was created by putting loose clumps of asbestos called flock around an object. This was then wrapped with 50% asbestos felt, in turn wrapped with a retainer fabric which was stiffened and painted.

Besides lagging, the forms of shipboard WWII asbestos were myriad. Valves contained asbestos gaskets. Asbestos could be made into fireproof rope. Internal decks often had floor tiles of pressed asbestos mixed with aggregate. These deadened footsteps to the deck below and were fireproof. Sheet asbestos could be laid anywhere fireproofing was required.

(Snippets from WWII US Navy manuals showing the stock numbers for sheet asbestos, and asbestos boiler line gaskets.)

As it was both fireproof and non-conductive, arc chutes in circuit breakers were sometimes asbestos, and important electrical lines often had asbestos over the wire’s insulation. In AC wiring, sometimes thin asbestos filaments were inside the wire. Post-WWII shipbreakers considered this especially obnoxious as the filaments were hidden to bid surveyors and not discovered until scrapping was underway.

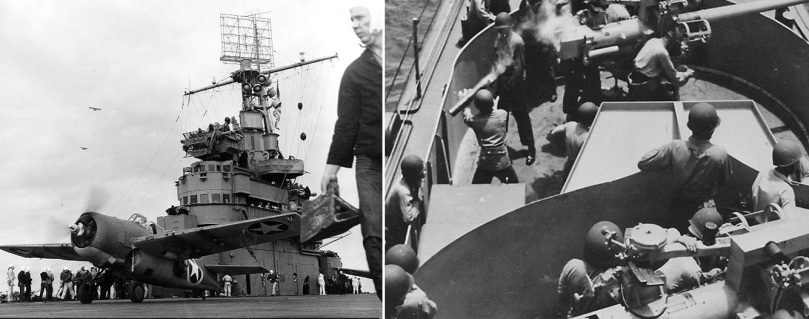

The left photo above shows USS Ranger (CV-4) during operation “Torch”. Under the F4F Wildcat’s wingtip is a crewman in full-body asbestos firesuit. WWII sailors called these men “Asbestos Joes”. The right photo aboard USS Jacob Jones (DE-130) during WWII shows a sailor catching a hot casing from the Mk22 3″ gun. His mitts are asbestos. Decades later, shipbreakers would find things like these stuffed into lockers long ago. Per EPA regulations they must be treated no different than any other asbestos.

If installed properly and undamaged, asbestos aboard WWII warships was benign. Problems started when it was broken, shaken, ripped, or otherwise disturbed. Then rigid microfibers are released into the air. If inhaled they cause serious long-term health problems; sometimes fatal years later.

Nine years before WWII, this was discovered. However the severity of the danger was underestimated. It was also just viewed as unavoidable. Nothing then existing duplicated all of asbestos’s many shipboard qualities.

During the Cold War, the US Navy reined in asbestos by using filler to lower the percentage of actual asbestos in lagging and developing substitutes altogether. This obviously didn’t help WWII-era ships already built. New asbestos use was abandoned in the 1980s. Shipbreakers assume any pre-1979 US Navy warship has asbestos unless known otherwise.

Asbestos abatement is incredibly expensive and usually the biggest profit-killer with scrapping WWII warships. In 1992, Southwest Marine purchased the ex-USS Bon Homme Richard (CV-31) for scrap. While being cut up, 50 tons of cable with hidden asbestos was discovered and had to be trucked out of California for disposal.

Polychlorinated biphenyls can be either liquid or solid. PCBs are electrically neutral and resist high temperatures. They were used in shipboard transformers and capacitors, mixed into hydraulic fluid, mixed into paint so that when it dried it was ductile on flexing ship hulls, and other uses.

During WWII PCBs had limited warship use; mainly transformers. A bigger problem was WWII warships retained in use by the Cold War-era US Navy. These ships, like modernized Essex class carriers, FRAM-upgraded destroyers, and GUPPY-upgraded submarines, received heaps of new PCBs in modern electronics and plastics.

Lead-based paint was used in warships of both world wars and into the Cold War. The problem for scrappers was ever-tightening regulations from the 1970s on. Naturally the bigger the ship, the bigger the amount of paint aboard; and during the 1990s this was one of the reasons the government had an especially hard time peddling WWII-built aircraft carriers and oilers.

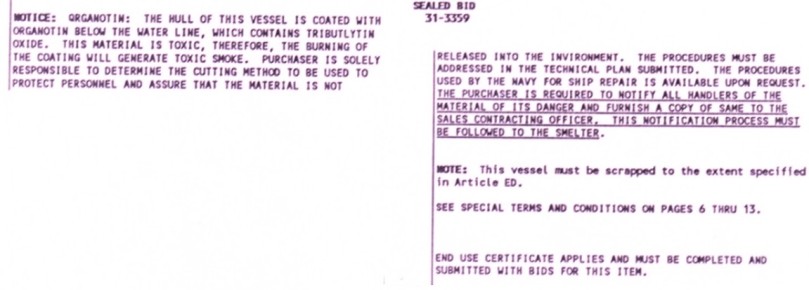

(Even after lead was no longer added, warship paints had problems. This notice about the ex-USS Coral Sea (CV-43), a WWII aircraft carrier, warns of tributlytin oxide in the exterior hull paint. This produces toxic smoke if burned. Prospective scrappers were required to notify everyone involved, down to the steel mill which refired the scrap metal, of this. It was another hassle and expense.)

There were other regulated wastes aboard WWII warships. Mercury was in switches and thermostats made during WWII, and lighting refitted afterwards. Hydrocarbon residue was common in oilers, tankers, and fuel lighters. A new category, especially for west coast mothballed ships, was “bio-contaminants”. The state of California felt that algae and barnacles were sucking up PCBs and mercury out of Suisun Bay, and when the ship departed for scrapping, these could die and fall off depositing the pollutants elsewhere. Several WWII warships including the ex-USS Nereus (AS-17) had to be expensively drydocked and cleaned before they were immediately scrapped anyways.

money hazards

Other than asbestos the biggest challenge shipbreakers faced from the 1970s onwards was metal prices.

Immediately after WWII steel prices were not an issue. After V-J Day scrap steel was $36/t ($519 in 2020 dollars) climbing to $40.50/t ($584) by 1948. Even if there was a weekly dip, shipbreakers didn’t care. Demobilizing GIs wanted cars and washing machines, and steel was needed for rebar in new roads, so it was an upward slope in the end. In an era of low regulation, it didn’t take much time to scrap a Liberty Ship or destroyer anyways.

The first really big problem came in the mid-1970s. A combination of market conditions and backfired government policies saw scrap steel go from $37/t ($205 in 2020 dollars) in 1973 up to $125/t ($653) in 1974, then down to $51/t ($233) by 1976. By 1978 it was back at the 1973 peak but by 1979 had dipped back to the 1976 levels.

(The nameless YSR-35 was a Yard & District Craft sludge barge of WWII. By 1975, it was in rough shape as seen and was sold for scrap. This was in the middle of the wild steel price gyrations.)

All this spelled trouble for shipbreakers. Auctions happened months before a contract was awarded. Then a tow had to be arranged, the ship had to be cut up, the metal sorted, and a steel consumer found to buy it. This all might take the better part of a year. If prices dipped 50% or 60% in the meantime, it was a disaster. The ex-USS Oriskany (CV-34) was sold for scrap in 1994, but the deal collapsed. Resold in 1995 to Pegasus Inc., steel price movements (along with the huge amount of asbestos aboard) bankrupted that company mid-job in 1997. By then, no shipbreaker wanted anything to do with the WWII aircraft carrier and it was eventually turned into an artificial reef.

It was incredibly hard for anybody in the USA to turn a profit on WWII warships by the 1990s. Literally, MARAD could not give ships away for free. In 1999 -2000, a “Cost +” program was launched. Here the government got nothing and instead paid a shipbreaker to just take the old vessel. MARAD and bidders negotiated what the true expense of safely and legally scrapping the ship would be (the “cost”), and another flat sum (the “+”) substituted for what would profit in a normal transaction.

(During WWII USS Clamp (ARS-33) had driven off five Japanese air attacks in one day. Sadly it will probably be instead remembered as the rusted ship which spent 64 consecutive years in mothballs. The Cost+ deal to scrap it cost the government $462,223.)

Just as an example, the government spent nearly a million dollars on a Cost+ contract to get rid of the ex-USS Bolster (ARS-38) and ex-USS Reclaimer (ARS-42) in 2011 – 2012. A decade or two earlier, the government could have made decent money auctioning the two WWII salvage ships.

the surveyor’s task

The job of the scrapyard surveyor was critically important and could make or break not only a deal, but the whole company. When bidding on a condemned ship opened, bidders were allowed to inspect the ship. They often only got a day or two to do so, sometimes just hours for smaller ships. Everything, good and bad, had to be noticed and factored in.

As a random example, the above photo from 2004 is the mess deck of the ex-USNS General Nelson M. Walker (T-AP-125) a WWII troopship untouched since 1968. Looking here the structural beams, plating, and bulkheads are all good HMS. The ductwork is Number 2 steel. The tabletops and chairs are breakage. There is almost certainly lead in the paint. The post-WWII lighting may have mercury and/or PCBs. The high voltage box on the far bulkhead has good copper, but probably also asbestos and PCBs. Good stainless steel will be in the galley behind the bulkhead. Copper will be in the bundled cables at upper right, but possibly also asbestos. The floor tiles probably have asbestos, if not they will be dunnage anyways.

The above 1999 photo is an empty compartment aboard the ex-USS Protector (AGR-11), a WWII Liberty Ship hull rebuilt into a Cold War radar picket warship. It decommissioned in 1965. Here the lighting probably contains PCBs and mercury, the flaking paint is lead-based, the bulkhead is good HMS, and pipes either HMS or Number 2. The bulkhead junction box is brass and contains good copper wiring but (depending if there is a transformer) also PCBs. The non-watertight door is dunnage. Obviously there is asbestos all about; MARAD had already hung a warning on the door to that effect.

fiascos

USS New Mexico (BB-40)

Unwanted after WWII, this battleship decommissioned in 1946 and was sold to Lipsett for $381,600 ($4.4 million in 2020 dollars) in 1947.

The episode got off to a bad start when a storm broke the tow lines off the battleship. It drifted away in the Atlantic (with Lipsett employees aboard) for three days until a US Coast Guard plane found it and the tow could be recovered.

Lipsett planned to scrap the ex-USS New Mexico and other large, expensive warships in Newark, NJ which had good railroad access. But that city was redeveloping the waterfront for postwar use. The mayor told Lipsett to take the ex-USS New Mexico elsewhere. Lipsett, a subsidiary of the then-powerful Luria company, protested that all the paperwork was in order and they had every right to break up WWII battleships in Newark.

The mayor in turn essentially said he didn’t care, and threatened to have city-owned boats hose down the tow tug crews with firefighting foam.

After a weeklong standoff (which was national news for several days), the federal government brokered a compromise that Lipsett could scrap only three ships in Newark, and had to be finished in nine months or less.

(The ex-USS Idaho (BB-42), ex-USS New Mexico (BB-40) behind it, and ex-USS Wyoming (AG-17) a gunnery training battleship during WWII, across the pier.)

Three ships were duly scrapped within the allotted time and the incident passed without further problems. The same can not be said of some later debacles.

USS Bennington (CV-20)

USS Bennington (CV-20) was a WWII Essex class aircraft carrier later modernized during the Cold War. Decommissioned in 1970, the ship was marked for disposal in 1993. The ex-USS Bennington had an appraised scrap value of $200,000.

In January 1994, Resource Recovery International of Stamford, CT won the auction at par ($200,000). As this company was clear across the country, it could not physically dismantle the WWII ship itself. Several months later, this company solicited an offer of $1,000,000 to the government to cancel the “domestic only” rule, which was accepted. The US Navy demilitarized the ship, removing or smashing below decks systems and finally dynamiting a hole into the flight deck, where the whole torched-off island was pulled down into.

(The ex-USS Bennington after the demilitarization.) (photo via uss-bennington website)

On 3 December 1994 Resource Recovery International sold the WWII ship to a British company (reportedly for $6 million) which immediately resold it to an Indian company who resold it again to a shipbreaker at Alang, India. On 7 December 1994 the ex-USS Bennington left the United States under tow.

Scrapping began in early 1995. The ex-USS Bennington became legendary in the shipbreaking industry, and not in a good way. Work was done by portable torches and hand tools. The job had the misfortune of happening while a reporter from the Baltimore Sun newspaper was visiting Alang. Readers were appalled at how this former US Navy warship was beached and being taken apart by Indian laborers in unimaginably bad conditions to earn $1 per day.

(ex-USS Bennington at Alang.) (photo by Baltimore Sun newspaper)

At some point either no schematics or the wrong schematics (the final SCB-125 Essex configuration was different than a WWII Essex) were provided, and the workers had no idea what much of the ship even was. One work team got lost for hours deep below decks as torching continued above them. At a certain point the lighting system stopped working and laborers were using candles and flashlights.

The ex-USS Bennington job finished in 1997. It led to a moratorium on exporting US Navy hulks.

USS Ashtabula (AO-51)

USS Ashtabula (AO-51), a WWII Cimmaron class oiler, was one of the US Navy’s most decorated auxiliaries in three wars over 40 years. USS Ashtabula decommissioned in 1982.

In 1995, Pacific Rim Metals won it at auction. This company had a mailing address in Issaquah, WA and had been created only several weeks prior to the auction. It was intended to actually scrap the WWII oiler near Seattle and the ex-USS Ashtabula was towed there from California.

The scrapping immediately ran into problems, the biggest being the huge amount of oil sludge and asbestos on the WWII ship. Over a 3½ year span, work started and stopped several times. By late summer 1999, only about 20% of the ship – the bow, the superstructure and topside refueling booms, and some of the weather deck – had been removed and the contract went into default. On 27 September 1999, the government repossessed the hulk and towed it (at taxpayer expense) to Mare Island, CA.

(The partially scrapped ex-USS Ashtabula back in California.) (photo by Kirk Rattenne)

At least bare minimal upkeep had to be done on it now (again, at taxpayer expense) to preclude it sinking pierside. The Maritime Administration already knew the prospects of another shipbreaker taking it on were dim: there was no guarantee the US Coast Guard would certify a commercial tow given the hulk’s situation, and Pacific Rim had already “cherry picked” many of the best things like brass fittings while leaving asbestos and lead paint aboard. Thirteen months later, MARAD gave up and the ex-USS Ashtabula was used as a target for a naval exercise.

(Even in its degraded state, the tough WWII oiler absorbed tremendous punishment including several anti-ship missiles.)

USS Coral Sea (CV-43)

USS Coral Sea (CV-43) was the third Midway class aircraft carrier. The keel was laid in mid-1944 as the Saipan battle was being fought in the Pacific and as the allies were pushing out of Normandy in Europe. Less those with knowledge of the Manhattan Project, it was expected that WWII would end sometime in 1946 and it was considered possible, but unlikely, that USS Coral Sea would be ready before the war’s end. It was more considered to be one of the cornerstones of America’s peacetime fleet.

As it turned out, WWII ended in September 1945 and USS Coral Sea was nowhere near complete. Work slowed and the ship was not commissioned until October 1947. USS Coral Sea had a long career including Vietnam War service and 1986 skirmishes with the Libyan navy. It decommissioned on 30 April 1990.

Concurrent with the end of the Cold War, USS Coral Sea was not desired for layup and was instead to be a template for future supercarrier disposal. Previously the largest warship scrapped intact had been USS Coral Sea‘s sister ship USS Franklin D. Roosevelt (CV-42) which had been broken up in the 1970s. Although the three Midways were built as sisters during WWII, modernizations to USS Coral Sea over the decades resulted in a slightly larger and much more complex ship than USS Franklin D. Roosevelt. Therefore it was generally felt that this job would be the biggest warship scrapping of human history at that time.

In March 1993, the Defense Reutilization & Marketing Service put the ship up for auction with an appraised scrap value of $300,000.

The winning bid of $748,999 was by N.R. Acquisition, a holding company incorporated in Nevada but operating in New York. The actual scrapping subcontractor was Seawitch Salvage Inc. of Maryland. The company was named after the Seawitch, its gigantic open holding barge.

The contract was specific, and mandated that all federal and state laws be followed. It also prohibited export of the carrier, and spelled out progress “milestones” to be completed by certain intervals of the allowed 15-month maximum. The contract noted that the aircraft carrier contained PCBs and asbestos. It was estimated that the big ship had about two linear miles of asbestos-insulated pipes of various diameters and 8,000’² of asbestos in other forms.

During the bidding, N.R. Acquisition hired American General Resources to survey the ship. Per the Pentagon this sufficed for due diligence to the hazardous materials aboard, however N.R. Acquisition later stated that surveyors had been prohibited from “intrusive investigation” (cutting sample steel, drilling into tanks, etc).

(The Seawitch and the ex-USS Coral Sea.)

In July 1993 the ex-USS Coral Sea was towed to Baltimore, MD; specifically to the Lambert Point Piers (today Fairfield Ocean Terminal).

From the get-go, the scrapping was beset by problems. Seawitch had constant cash flow difficulties. An unrelated scrapping of a 1950s-vintage minesweeper resulted in a net loss to Seawitch, exacerbating the cash flow issue. The US Navy was hesitant to release full blueprints of the ship, slowing progress. A serious crane accident delayed work. The biggest problem was the asbestos aboard.

The contract mandated asbestos removal be done by a Maryland-licensed remediator (of which Seawitch was not) and a subcontractor was hired. However the subcontractor later said they only worked aboard the ex-USS Coral Sea for a month, thereafter all asbestos removal was done by Seawitch employees, who were neither licensed nor trained.

The EPA placed two informants aboard the ex-USS Coral Sea. One observed a section of flight deck being torched off and allowed to plop into the hangar deck (this act itself unsafe) which caused a huge dust cloud of likely-asbestos containing material to puff out and then settle into the harbor. Another confidential whistleblower said that asbestos was being stuffed aboard the Seawitch because Seawitch (the company) had insufficient cash-on-hand to pay anybody to truck it away. To be certain, there were a lot of workplace safety problems. A Defense Department inspector refused to board the ex-USS Coral Sea at all due to the unsafe way the carrier was being scrapped. An anonymous whistleblower said that acetylene cutting was done with firehoses not even turned on, let alone manned as required by OSHA.

PCB remediation costs were $200,000 more than had been estimated during the bidding. Asbestos remediation costs climbed well over $1 million.

In October 1994, N.R. Acquisition petitioned the government to waive the “no export” clause and allow the ex-USS Coral Sea to be scrapped in Alang, India. This was denied.

In 1995 N.R. Acquisition terminated Seawitch and hired Kersand Corporation, which was described as a “successor company”. In 1996, Kersand was itself terminated and replaced by Patapasco Recycling.

In March 1996, N.R. Acquisition submitted a claim for $8,871,416 to the government on the grounds that DRMS had not been forthcoming on how much hazardous material was aboard the ex-USS Coral Sea with a caveat that this could be reduced to $3,726,416 if the “no export” clause was waived and permission granted to finish the job in Asia. The $8 million claim was rejected outright and the idea of scrapping the carrier in China or India was shunned by the Pentagon.

In September 1996 Seawitch as a company and its CEO as an individual, were indicted by a federal court. The corporate violations were the Clean Air Act (for mishandling asbestos), the Oil Pollution Act (for allowing fuel and lubricants to leak off the ship), and illegal dumping (for workers just throwing debris overboard). The CEO was indicted on fraud.

In August 2000, five years later than planned, the ex-USS Coral Sea job ended. Needless to say nobody involved looked good. Seawitch, unsurprisingly, went bankrupt. As far as the government, it had a much harder time disposing of warships – especially WWII warships – as fellow shipbreakers actually quietly agreed with N.R. Acquisition’s allegation that the federal government had sold “a bag of worms” full of hidden profit-busters. Shipbreakers were hesitant to bid at all on WWII warships.

Aircraft carriers especially became like kryptonoite. While the well had gone dry for remaining WWII carriers, the ex-USS Coral Sea made it exceedingly hard to find anybody to scrap modern Cold War-era flattops. The ex-USS Forrestal (CV-59), the first post-WWII carrier, was sold to a shipbreaker for 1¢ in 2013, as was the ex-USS Saratoga (CV-60) a year later.

postscript

In the 2010s, a gruesome sideshow to this industry was discovered in Asia. In seas off Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei; criminal enterprises are leasing derrick barges and illegally ripping up WWII wrecks, still with human remains in them, for scrap steel. In Indonesia this is referred to as “magnetik memancing” (magnet fishing). In 2014 it was discovered that the sunken HMS Prince Of Wales had been tampered with. Some sunken WWII Dutch warships were completely gone by 2016.

(Japan’s light cruiser IJN Kuma was sunk off the Malaysian coast during WWII, taking 138 sailors down. The wreck was plundered in 2014.) (photo via Malaysia Star newspaper)

Many problems don’t just go away on their own, but for the predicament of how to dispose of America’s WWII’s warships, by 2020 it largely has. They simply are all gone by now.

The last big mothballed WWII ships on the west coast were the submarine tender ex-USS Nereus (AS-17) and oiler ex-USS Mispillion (AO-105). Both were towed to Brownsville for scrapping in 2012.

(The ex-USS Gage was heavily rusted by the late 2000s.)

The last big mothballed WWII ship on the east coast was the attack transport ex-USS Gage (APA-168). It had bounced between three different mothball fleets since 1947. It was towed from James River, VA to Brownsville in 2009 and scrapped.

Surprisingly there are still a very few minor, uncommissioned service vessels of WWII still in the US Coast Guard and US Navy in 2020.

(The nameless repair barge YR-29 entered service two weeks before the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941. As of September 2020 it is still in use at Norfolk Naval Base.) (photo via navsource website)

Eventually these too will be scrapped but they will be no problem to the 21st-century shipbreaking companies in Brownsville, who are now more of an artisanal craft than an industry.

All of the onetime big players: Lipsett, Joffe, Boston Metals, Andy International, Esco; are either closed down or bankrupt years ago now.

MARAD still exists but the DRMS does not. It was rolled into the Defense Logistics Agency.

Zidell played its cards right. It transitioned out of the saleables area in the 1970s as the last Liberty Ships and T2s were about to leave commercial service, and exited the WWII warship dismantling sphere several years later just as regulations tightened up. In 2017 it exited its last operation at the 1940s yard, a barge-building division, but as of 2020 is still involved in the maritime industry.

Fascinating. Thanks for writing this; even though you thought it was not WWII after WWII regular fare, it was still a great read. More, soon, please.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I looked at your pictures of old battleships from Pearl harbor…loved seeing those. I was 13 when the USS Maryland was scrapped in Oakland at the Todd naval shipyard. She had retained enough of her Pearl Harbor looks, that it made me sad she was never maintained as a museum ship and towed back to Hawaii to her old berth at Pearl harbor, and kept as a museum display. I have a picture if you want it

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] scrapping the warships of WWII […]

LikeLike

The postwar miracle of Greek shipping begins in 1946 with the 100 Libertys. Whenever a round anniversary comes Greek shipping media mention them, with the biggest celebration being in 1996 during the 50 years. Apparently at the time the US government did not allow Liberty ships to be sold to foreign shipowners. The Greek government intervened, being a time that Greece had a lot of crews but few ships to man, and came to an agreement with the Truman administration to be an intermediary. It bought the 100 ships, 15 of which were crewed by Greek merchant marine crews and flying the Greek flag from 1944 and sold them the same day to Greek shipowners. Something like 400-500 Liberty ships served under Greek interest, though rarely the Greek flag. The newspaper Kathimerini had a special issue in 1996 or 1997 that actually had a table of all Greek owned Liberty ships ever used, most likely from Llody’s. Entire volumes have been published over them, this link should be of interest over the 100 Liberty ships; though it is in Greek you can use Google translate.

https://www.enandro.gr/istoria/3857-%CF%80%CF%8E%CF%82-%CE%B1%CF%80%CE%BF%CE%BA%CF%84%CE%AE%CE%B8%CE%B7%CE%BA%CE%B1%CE%BD-%CF%84%CE%B1-100-%CE%B8%CF%81%CF%85%CE%BB%CE%B9%CE%BA%CE%AC-liberty-%CE%BA%CE%B1%CE%B9-%CF%87%CF%84%CE%AF%CF%83%CF%84%CE%B7%CE%BA%CE%B5-%CE%BF-%CE%B5%CE%BB%CE%BB%CE%B7%CE%BD%CE%B9%CE%BA%CF%8C%CF%82-%CE%BC%CE%B5%CF%84%CE%B1%CF%80%CE%BF%CE%BB%CE%B5%CE%BC%CE%B9%CE%BA%CF%8C%CF%82-%CF%83%CF%84%CF%8C%CE%BB%CE%BF%CF%82.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

Absolutely fascinating. Very well done and keep on writing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

EXCELLENT site you have here. I have been enjoying it immensely!

On the subject of Victory Ships, U.S. company Cleveland Cliff bought a Victory Ship in the 1951. They had it converted into a bulk ore carrier to run on the Great Lakes. It was one of a kind and one of the fastest Lakers. Here is a YouTube video of the conversion.

Notre Dame Victory 1945 – 1951

Cliffs Victory 1951 – 1985

LikeLiked by 2 people

thank you

LikeLike

A fascinating article about an oft-overlooked topic, greatly appreciated!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another excellent addition to this most fascinating website.

Being a navy person (Aussie), the scrapping of these vessels is always met with a tear. Especially the more famous and historic ones.

However you raise a few interesting points, in particular how the business of scrapping former WW2 US Navy vessels went from a profitable one to then one costing the government. Also how the ever increasing environmental concerns are becoming an ever more a bearing factor on the scrapping process.

Now we have the extraordinary situation where post WW2 and Cold War US ships like, for example the former USS Enterprise is sitting idle waiting for it’s ultimate doomed fate. The costings to have this vessel reclaimed are unbelievably astronomical. In this case the problem not only being dangerous materials but now the added issue of the Nuclear Reactors and the best way to undertake the task.

Obviously little thought went into how to dispose of the vessel when the time came. From my understanding the changing of the reactors was very difficult due to the design not making easy provision to achieve this task. This also causing her to be retired when there was still life in the hull. I believe the newer carriers will make this task easier. Perhaps more thought will go into future designs on how these problems can be addressed at the design stage.

Thanks again for the article, and I agree it fits in perfectly well into the theme of the website and its stories.

Keep up the great work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The ex-Enterprise thing is turning into an utter debacle. It is still on the east coast here, nowhere near where it needs to be in Washington state to extract the reactors. The original estimate (six years ago) was $500 million max over 5-9 years. Now it is $1.7 billion which is the cost of a new Burke class DDG, and it would not finish until the mid-2030s by which time Nimitz and probably another CVN will join it.

LikeLike

Really been enjoying the articles.

While the last mothballed WWII ship on the east coast was the USS Gage, there was another that went straight from active use to auction where it sold for actual money (1.4M!). The USS Oak Ridge was a WWII floating drydock that entered service in 1944, was struck by one kamikaze and shot down a second. Modernized in the 60’s to support submarines and then in the early 00’s transferred to the USCG where it served again as a floating drydock in Baltimore until 2018.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hello, I work for the EPA and we’re sorting trough a shipbreaking yard in the Southeast. I’m looking for specifics about the materials used in the construction of Liberty ships; what alloys of steel were used, what were the additives in the paint both above and below the waterline. I know about the asbestos, the PCBs and residual fuels. If you know these details or know where I can find them, I would appreciate you being in touch and it would help cleanup a Superfund site. Thanks.

LikeLike

The hulls, which were riveted and not welded, used commercially-available killed steel which was not to any MILSPEC. The “red lead” primer which was used in the 1940s typically was mixed 800,000ppm which is naturally very high. I would take it with a grain of salt because every Liberty ship was certainly repainted at least several times after WWII; most often using commercial paints which was probably whatever was cheapest. Hope this helps.

LikeLike

[…] scrapping the warships of WWII — wwiiafterwwii […]

LikeLike

Wonderful article! Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating review of the last phase of life for the great vessels of WW2.

We easily can understand the changing requirements of naval power, but reading this made me sad, nonetheless.

Thank you for the enormous effort at curating and documenting the photos, as well as detailing how ships were scrapped.

LikeLiked by 1 person

loved this..very sad in many cases…… Thx… MB

LikeLiked by 1 person

I grew up in Portland and Zidell was an am annual trip for me and the neighborhood kids.

Purchasing rifle stocks, gas masks, steel helmets, goggles etc. Each ship dismantled was fully stocked with EVERYTHING but perishables and ammo down to coffee cups, silverware and cots, signal flags, rafts , you name it!. The warehouse was FULL of such items and smelled a wonderful combination of grease, canvas and steel. All our Dads were WW2 veterans.

Piles of 5 inch guns stacked like cordwood., crashing and groaning of breaking these ships. It was a great time (50-s early 60’s ) to grow up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Been a fan of this blog for a long time. I wonder if I can translate some of the articles and repost them elsewhere?

Just recently visited a coal powerplant under deconstruction and immediately recalled this article. There’s a striking amount of similarities between scrapping ships and decomposing powerplants from what I saw.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes no problem.

It is funny you mention that because one of my clients at work deconstructs old electrical high-voltage substations. The amount of nasty stuff (PCBs, toxins, etc) in those is staggering.

LikeLiked by 1 person