The Tokagypt, Hungary’s odd Egyptian-contract post-WWII TT-33 half-clone, is somewhat known in the firearms community. It appears in any number of books from the relatively entry-level Small Arms Visual Guide up to professional-grade publications. Yet in either case, the level of information is often similar and very brief: it was a 9mm copy of the Tokarev, it was made for Egypt, they didn’t want them all, some were used by terrorists…..and little else is usually explained. So perhaps this will be of value to those interested.

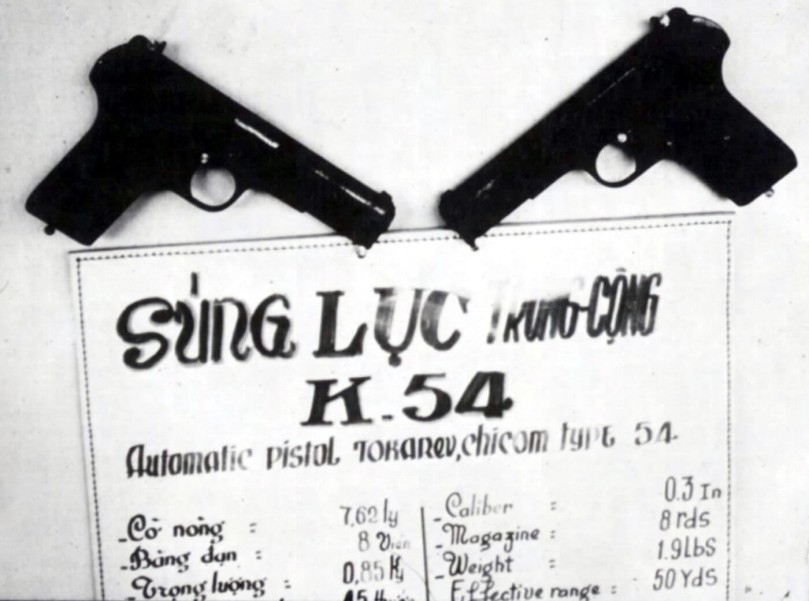

(August 1983 American intelligence photo of a Tokagypt.)

the TT-33 of WWII.

The original TT-33 was developed by Fedor Tokarev (the gun itself is often just called “the Tokarev”) in 1933 as a refinement of his TT-30 design. The goal was a standardized replacement for revolvers still in the Soviet army. It is 7½” long and weighs 1 lb 15 oz empty. Utilizing the blowback principle, the TT-33 fires the 7.62x25mm Tokarev cartridge from an 8-round magazine. The same Tokarev cartridge was also used by the PPSh-41 and PPS-43 submachine guns, two other WWII weapons that saw significant post-WWII use. No safety was included in the TT-33 design; to accomplish this a half-cock was suggested but in practice this was dubious.

(This TT-33 is pre-WWII or WWII production, as identified by the “organ pipes”-style slide grasp which had to be machined on. Near the end of WWII, a cheaper simple stamped-on serration was substituted.)

(Entitled Kombat, this is probably the single most famous Soviet battle photo of WWII and remains culturally iconic in Russia today. The handgun is a TT-33. During the 1970s Pravda newspaper traced the identity of the man to Aleksei G. Yeryomenko, a commissar KIA on 12 July 1942, the same date the photo was taken.)

Tens of thousands of TT-33s were in Soviet use when the USSR entered WWII in June 1941. However the type had not yet fully replaced the Nagant M-1895 by a long measure, and in fact, the revolver was deemed faster and cheaper to make than the TT-33 and about a quarter-million were manufactured between the 1941 German invasion and V-E Day in 1945.

(A WWII-built M-1895 with a Tula proofmark of 1941. These remained in production alongside TT-33s.)

Germany used captured TT-33s under the Wehrmacht designation Pistole 615(r). German 7.63x25mm Mauser ammunition was dimensionally similar enough to 7.62x25mm Tokarev rounds that it could be used in TT-33s, however, the Tokarev cartridge could not be used in Mauser c/96 broomhandles. It is said that the very first look US Army intelligence got at the Soviet pistol was in fact Pistole 615(r)s captured completely on the other side of Europe during the “Overlord” landings in Normandy. This may be apocryphal but for certain there were TT-33s captured in Normandy as photographic evidence exists.

Even though there were still Nagant M-1895 revolvers in Soviet use during the 1950s, the USSR already set about to discard the TT-33 in favor of the 9x18mm Makarov as soon as possible. The 7.62x25mm Tokarev cartridge (1,378fps muzzle velocity) was considered to lack stopping power in battle, and in any case the round’s other consumers (the PPS-43 and PPSh-41) were themselves out of production and being replaced.

(Soviet-made ammunition for the TT-33: the large 70-round box is the early Cold War export packaging style, the 35-round style was used from roughly 1970 to the collapse of the USSR in 1991, and finally the original WWII twine-tied 16-round paper bag.)

Starting in 1948 – 1949, TT-33s began to be dumped into the post-WWII armies of eastern Europe, which accelerated in 1955 with the creation of the Warsaw Pact. The pistols were also made available for other users and TT-33s spread around Africa and Asia. The TT-33 was also copied, either with license or without, by several countries (including Hungary) and of the 1.7 million the Soviets made; probably an equal quantity of licensees, clones, knock-offs, and variations were built elsewhere after WWII.

TT-33s continued to appear on the world’s battlefields for decades after WWII.

(China’s clone of the TT-33 was the Type 54; these two being captured by South Vietnamese troops during the Vietnam War.)

(Soviet-made TT-33s for sale in Sanaa, Yemen in 2015. The Tokarev appears with some regularity in the ongoing Yemeni civil war. The gun on the left has the “organ pipes”-style serrations meaning it was made before or during WWII.)

Hungary and the TT-33

Hungary was originally part of the “minor Axis” in Europe alongside Bulgaria and Romania. In 1944 with defeat inevitable, Hungary tried to achieve a separate peace with the Soviets but was occupied by Germany. In September 1944, the advancing Soviets crossed the Hungarian border. In February 1945, the 1st and 2nd Waffen-SS Panzer Corps and the Wehrmacht’s 6th Army mounted a failed counteroffensive in Hungary to retain what was by then Germany’s last source of crude oil, and with that WWII effectively came to an end in the country. WWII in Europe ended altogether about 2½ months later.

In 1946 the Hungarian monarchy was abolished, and in 1947 a treaty signed in Paris legally ended the state of hostilities. The postwar government was soon dominated by communists and in 1949, a blatantly pro-Soviet “people’s republic” was declared.

FEG

Fegyver-és-Gázkészülékgyár (Weapons And Gas Equipment Factory), or FEG, traces its roots to several late 19th century Hungarian gun companies. Prior to the communist takeover (when for political reasons, it was briefly renamed Lámpagyár or Lighting Factory), Hungary’s best-known pistols were the Roth-Krnka M.7 of WWI and the Femaru M.37 of WWII.

(Some Femaru M.37s leftover from WWII continued in Hungarian army use until the failed 1956 rebellion and very limited thereafter.)

In 1947, licensed production of the Tokarev TT-33 began at FEG, under the Hungarian designation M.48. There were no changes, other than the Hungarian coat of arms being substituted for the USSR’s CCCP star on the bakelite grips.

(The FEG M.48, the post-WWII Hungarian exact clone of the TT-33. This one was made prior to mid-1956 as it has the first communist coat of arms.) (photo via hungaraie.com website)

Production ran from 1947 to the failed June – November 1956 uprising, and then briefly restarted in 1957 before ending altogether in 1958. In all, about 100,000 M.48 clones were built by FEG after WWII. Hungary also license-manufactured the WWII Tokarev cartridge under the designation “48M 7,62 Pisztolytolteny” at the Andezit and Bakony factories.

Hungarian arms export posture during the Cold War

From the 1956 Soviet invasion through late 1958, the Hungarian army was partially stood down and reformed along Warsaw Pact lines, with most WWII-era weaponry not of Soviet origin being flushed out in favor of combloc-standard gear. The Hungarian air force was treated even more harshly; it was completely grounded and basically rebuilt from scratch.

(A Hungarian freedom fighter during the 1956 uprising. The rifle is a FEG M.43 of which 86,500 were built for the Hungarian army during WWII, plus about 15,000 until 1948, when production ceased in favor of Mosin-Nagants. The destroyed Soviet army ISU-152s behind her are also WWII weapons. After the uprising, FEG retooled to make the AK-47 as a joint replacement for Mosin-Nagants and non-combloc WWII rifles, under the designation AK-55.)

Surprisingly Hungarian defense industries did not suffer a similar fate and continued on much as before.

Under Janos Kádár, who took over after the failed uprising, an “unofficial deal” became national policy, in that in exchange for Hungary’s people accepting their political fate, the government would legitimately provide at least a semblance of a tolerable consumer lifestyle. One of the ways this was accomplished was through government debt, and lots of it. By the 1980s it was said that Hungary was the most indebted Warsaw Pact member. Post-Cold War forensic accounting indicates that East Germany and Romania were both probably even worse off, but in any case, Hungary had a lot of national debt during the Cold War – even already at the close of the 1950s.

One way to alleviate this was weapons exports. A government “trade company” called Technika (also known by its Magyar-language abbreviation, TKV) was created to conduct overseas deals in guns, ammunition, spare APC parts, radars, and so on. Technika was government-owned but effectively independently-run. Other than a final approval on arms deals being needed by the Ministry of Defense (nearly always a rubber stamp), Technika was largely left to its own devices.

Technika in Hungary was by no means unique behind the Iron Curtain. In communist Bulgaria, Kintex had the same role. In Czechoslovakia, there were not one but two such companies: Merkuria and the famous Omnipol. In particular, Omnipol was extremely prolific and successful. For almost four decades it was practically a household word in worldwide weapons dealing and arms smuggling.

Another Hungarian organization which had unclear ties to Technika during the Cold War was Ferunion. Its niche was adaptations of military arms for police or recreational civilian use; perhaps the most famous being the “SA-85” (a semi-auto only AK-47) and Warsaw Pact-surplus 9mm Makarov ammunition which it marketed under the “FMS” moniker. Ferunion often operated in places where Technika did not desire a public face (or would be unwelcome) such as gun shows in NATO-member countries. Ferunion was not atypical of Warsaw Pact members. For example in Cold War-era Poland the company Universal filled a similar niche for Cenzin, the Polish counterpart of Technika.

(One of the WWII Mosin-Nagants which had been remanufactured and scoped by FEG, then sold by Technika to North Vietnam for use by VC snipers.)

As it existed solely to obtain “capitalist-world” western currencies to buttress the Hungarian government’s domestic spending (the Cold War-era version of the Hungarian forint not being internationally transactable), Technika always demanded payment in British pounds, American dollars, West German marks, etc. The only known exception was North Korea which for some reason was allowed to use Soviet rubles. Otherwise, everything had to be in western money. Obviously the USA’s greenback was always good but the West German mark was also favored, as it was a workhorse in Cold War-era European banking. (This is one of the reasons so many Tokagypts entered the west through West Germany.)

Technika in Hungary was not the juggernaut which Omnipol in Czechoslovakia was, but all things considered, it boxed ahead of its weight class in the arms market. Technika-brokered sales appeared around the world. In one such instance during the Vietnam War, the US Army captured some WWII Mosin-Nagant 91/30s refurbished by FEG and marketed by Technika. North Vietnam was not alone in receiving these rifles, which Technika moved under the names M.44/56 (rebuilt ex-Soviet Mosin-Nagants) and 48 Minta (the M-48 carbine version made under license).

Technika also imported non-combloc weapons into Hungary, including a buy of 9mm Uzis from Israel that went to special police units. The company also imported Soviet gear from the other non-USSR Warsaw Pact members, as within the alliance, allocations were determined by a standing committee that made decisions at a sloth’s pace insufficient for minor unexpected needs.

Finally, Technika also was a “laundromat” in that if a communist nation wanted to simultaneously sell weapons to two other countries fighting each other, Technika acted as a re-exporter on one of the two deals to avoid embarrassment for the originating country. To the same, it also served countries like Nigeria or North Korea wishing to import Soviet arms without angering a rival benefactor, in North Korea’s case that being China and for Nigeria, the UK.

Overall Technika was a success. As it was a governmental branch of a communist country it was impossible to “lose money” in the capitalist sense, but if one used that metric it was at least break-even throughout the 1960s – 1980s and often outright profitable. It led Hungary to create copies such as Technoimpex which dealt the same way but in high-end lathes and industrial machinery.

Egypt’s search for a sidearm

Egypt became independent in 1922, albeit with its territory dotted by British military bases and a strong British presence in Egyptian politics. During WWII, Egypt contributed four infantry regiments and two horse/camel cavalry regiments, plus obsolete artillery units. These were viewed as unsuitable by the British and rarely saw combat. Egyptian anti-aircraft guns in Alexandria self-defended their city alongside British AA units and were viewed more favorably.

(Egyptian infantry during a WWII gas drill. The masks are the Mk.IV, a pre-WWII design made by Siebe, Gorman & Co. in the UK. They remained in use until modern Soviet gas masks replaced them in the 1950s – 1960s. The fez, a relic of the Ottoman era, fell out of use after Nasser took over.)

Oddly enough, even when the Italians were occupying part of Egypt and Egyptian cities were being bombed by the Luftwaffe, the country didn’t declare war. Egypt finally declared war on Germany in early 1945. However fighting had long since ended in the middle east and this was merely to secure automatic entry into the U.N. as it was created.

Trying to identify the “standard” Egyptian sidearm of WWII is a fool’s errand as quite simply, none was. In the pre-Nasser Egyptian army, the officer corps was based on social connections and family name, with little regard to actual skill. Sidearms were mostly considered an officer’s item, and it was customary for officers to select and purchase with his own money a pistol, of whatever type in whichever caliber he desired. This was not only permitted, but more or less expected.

(King Farouk I three years after WWII ended. His sidearm is a Belgian-made HP-35.)

Immediately after WWII ended and running for about 4½ years, Egypt’s King Farouk I went on an ill-advised arms-buying spree to take advantage of surplus WWII arms; many still being warehoused at British bases in Egypt.

There was no rhyme or reason to the buys and purchasing was done with no overall plan of any sort. Any WWII surplus was bought, from rucksacks to fighter planes to tanks to mess kits to navy destroyers. Often they were bought in odd-sized lots, and frequently in quantities too low to be effective battlefield assets. Sometimes systems were bought incompatible with existing Egyptian kit.

(Egyptian soldiers on maneuvers during 1954. The water-cooled machine gun is a Vickers Mk.I and the helmets are Mk.II tommys; both WWII British items. Both were still in Egyptian use into the 1960s.)

Egypt voided its pre-WWII defense treaty with the UK in 1951, ending the country’s favored status to WWII-surplus British weapons. In 1952, a group of army officers overthrew King Farouk I and made Egypt a republic. These two events marked the end of the post-WWII arms buying spree.

(A general speaks shortly after the 1952 revolution. Overhead are WWII Lancaster strategic bombers. King Farouk I bought nine of these from RAF surplus four years after WWII ended. Expensive to buy, expensive to operate, and too few in number; they accomplished nothing. Two were hit on the ground by Royal Navy jets during the 1956 Suez conflict and the rest were never flown again.)

Through all of this, a standardized handgun was of little apparent concern. Sporadic lots of Webley Mk.IV, Webley Mk.VI, and Enfield No.2 revolvers were acquired but in no great quantity, joining a mish-mash of types from WWII and before.

In the above photo the holster appears to be a Ptn. 1940 leather model, a British design of WWII suitable for the Enfield and Webley revolvers in use during WWII. The occasion was the creation of the al-Qahira Army, a civilian militia hastily raised in Cairo during 1956 should the French and British have carried the Suez operation deeper into Egypt. This short-lived ragamuffin force was armed with ex-British rifles of WWII and WWI, interspersed with civilian guns.

(This Webley Self-Loader Mk.I chambered for .32ACP – aka the “metropolitan model” – was used by the Egyptian National Police during WWII and the postwar era. Above the serial number is the crescent & stars police mark then in use. The more famous .455 version was used in small numbers by Egypt’s army and later, also the police. The Webley Self-Loader was a British WWI weapon and not a great one at that; during WWII it was mainly employed by Royal Navy watchstanders.)

Starting in 1955, Egypt shifted to the east bloc for its weapons needs. This picked up after the July 1956 nationalization of the Suez Canal, and following the Suez conflict that year, the switch became whole.

(An Egyptian M4 Sherman tank of WWII destroyed during the 1956 Suez conflict. Between the 1948 war against Israel and the 1956 fighting; most of deposed King Farouk I’s post-WWII spending spree was wasted.)

In August 1955, representatives of the USSR and Egypt met in Prague, Czechoslovakia and inked a $200 million ($1.84 billion in 2020 dollars) arms package. Of this, Egypt paid only about 40% which was none the less a staggering hit to the Egyptian exchequer. The signing was done in Prague to create a fiction that Czechoslovakia, not the USSR, was the main counterparty. (The Czechoslovaks did get some small orders of their own from the event.)

From this (quite ironically, given the later Tokagypt story) came the Egyptian army’s first “standard issue” sidearm: none other than WWII-surplus TT-33s from the Soviet army. These were just a stop-gap however, and delivered in insufficient quantities to be a force-wide pistol.

Several months after the Prague treaty, a separate memorandum was signed in Budapest, opening the way to direct Hungarian sales of weapons.

the Tokagypt order

In 1957 a FEG gunsmith named Ambros Balogh examined the basic WWII design of the TT-33 and considered how it might be improved and kept relevant on the international stage. As FEG was already license-building the TT-33 as the M.48, all relevant data to that pistol was available.

The first and most obvious difference is that the new gun, which FEG designated “TT-9P”, switched from the Soviet WWII Tokarev cartridge to the worldwide-common 9mm Parabellum.

There were other changes. A safety was added. The operating method was changed from the blowback principle to the recoil principle. The bakelite handgrip was changed to a wrap-around style. The lanyard eyelet was relocated. The magazine’s capacity was reduced by one round. The rifling inside the barrel was changed.

Despite the changes, the basic shape, size, and design of the WWII-era TT-33 was retained. While internal parts differed in dimension and sometimes in function, the new Hungarian gun was still similar enough that any soldier who could field-strip a TT-33 would have no problem. The craftsmanship at FEG was higher than that of WWII Soviet production. Overall this was a good half-clone, exceeding its own original.

The Egyptian army was impressed and in 1958, placed an order for 30,000 with an option on future additional buys. This was a “hard cash sale” meaning that it used a western currency and was not financed. The per-gun price is unknown, but it is certain that the contract demanded payment only in British pounds.

The Egyptian army intended for this gun to be their standard sidearm in the 1960s and beyond. As it came to pass, this would not be, for reasons described later below.

a look at the Tokagypt

Neither FEG nor Technika ever delineated a “series” for the Tokagypt (a portmanteau of Tokarev and Egypt). However, pistol experts and gun authors worldwide recognize seven versions, all differing only cosmetically, and this is followed here.

1st version

All which made it to Egypt (plus some undelivered) are of this version, which had brown bakelite grips and a knucklerest on the magazine’s bottom. The gun has on the left side of the slide “TOKAGYPT 58 Cal. 9mm Para.” and “Made in Hungary FÉG 1958”, separated by the Egyptian emblem. The serial numbers were prefixed by “E” for Egypt and ran sequential. The right side of the slide was blank. The Tokagypts were delivered in a cardboard box with two magazines, a cleaning rod, and a used paper target to show that they were proof-fired.

Major parts are stamped “02” which was the Warsaw Pact’s internal code for weaponry made in Hungary.

For certain 13,250 were made, as that many were delivered to Egypt before the contract collapsed. Based on known serial numbers, an additional quantity (probably about 300) were completed as-is but then sold to other buyers.

The Egyptian symbol on these Tokagypts is obscure, rarely seen elsewhere, and often misattributed. It was certainly not invented by the Hungarians as is sometimes claimed, nor was it added later by civilian importers as is also sometimes stated. It was also not Egypt’s national coat of arms.

(The coat of arms of Misr (Egypt, in Arabic) around the Tokagypt project’s relevant timeframe: the design used during WWII until 1953, the design used from 1953 – 1958, and then the U.A.R. coat of arms from 1958 – 1971.)

The symbol was also not the Egyptian army’s emblem during the 1950s, which is shown below:

It is also not an Egyptian firearms receiver stamp, the relevant timeframe being shown below with the post-1953 version on a FN-49 rifle and the post-1958 version on a FN Hi-Power handgun.

Nor is it an Egyptian National Police property mark, shown below on a WWII Lanchester submachine gun imported for police use after the war:

This perched falcon symbol was actually an Egyptian uniform cap & collar device used only very briefly during the mid-1950s.

Obscure in and of itself because of its short duration in use, it is even more rare as a firearms motif. Many guns delivered to the Egyptian army after the 1953 revolution were already “in the pipeline” and still had the older crown crest receiver mark, while anything ordered after 1958 had the U.A.R. symbol. This symbol appears on the Tokagypt, the Walam, and little else in the way of firearms.

2nd version

The left side of the slide says “PARABELLUM Cal. 9mm” but otherwise there are no other markings, other than the “02” on parts and the serial number. Otherwise these are identical to the 1st version.

It is thought that roughly 8,000 Tokagypts were made this way. The serial numbers start sequentially with the end of the 1st version but then jump around nonsensically (this may have been intentionally done by FEG). These were also the first to appear outside Hungary and Egypt, even though they were built after the tail end of the 1st version.

3rd version – the first Firebird

(photo via Silah Report)

This version’s magazine omitted the knucklerest. The slide says “FIREBIRD KAL. 9mm”. These are otherwise identical to the 2nd version.

As evidenced by the switch from “Cal.” to “Kal.”, these were made with the intent of later selling them to commercial buyers in West Germany. Fewer than 3,000 were made and there is no pattern to their serial numbers.

4th version

(photo via hungariae.com website)

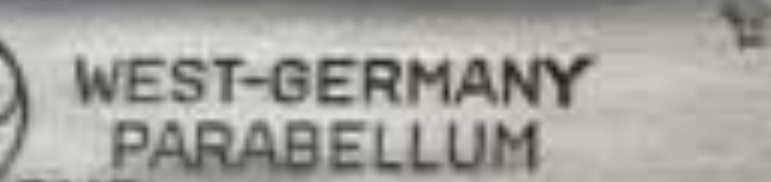

These were also made for commercial export to West Germany and appropriately enough, the only markings are “WEST GERMANY” on the slide’s right side and the “02” markings. This version returned to the knucklerest-style magazine bottom.

This is the least commonly seen version and the total built is unknown. The serial numbers have no sequence.

5th version – the later Firebird

This version has, in addition to the normal lanyard attachment, a smaller eyelet on the magazine which lacks the knucklerest.

The left side of the slide has “FIREBIRD KAL. 9mm”, then an apparently-meaningless three tangent circles inside a circle, then “WEST-GERMANY PARABELLUM” and the serial number behind the trigger.

(On this Firebird, “a.w.z.” is the importer’s mark of Albin Wahl in Zella-Mehlis, West Germany.) (photo via Silah Report)

The number built is unknown. This version was highly prolific in Europe and is the most commonly-recognized Tokagypt version. The serial numbers are again all out of sequence. Amongst firearms historians, there is debate whether the 5th version was manufactured before or after the 4th.

6th version

The so-called “sterile Tokagypts”; these are thought to to be 1st version guns never delivered to Egypt with everything (including the E serial number prefix) removed at the FEG factory.

The number built is unknown. Some serial numbers are below 13250 which may suggest factory seconds later brought back up to spec (there are no known problems or mechanical flaws with this version). The more colorful explanation, that they were intended for “untraceable” sales to terror groups, has nothing to back it up especially as the “02” (Hungary) parts markings are present.

7th version – the Super 12

The Super 12s were the last Tokagypts. These guns were shipped with the cheaper, no-knucklerest magazine and a different serial number system. It is claimed that these were 2nd version Tokagypts with new additional markings added years later outside of Hungary, by an importer seeking to “spice them up” for the USA’s recreational civilian market. The alternate explanation is that the changes were done in Hungary around 1989 – 1990 when communism was collapsing, and then sold to a German importer. The end goal was the same, to offer a pistol more appealing to American sportsmen.

On the slide’s left side is a rather crude Soviet Union hammer & sickle (nothing in these guns was made in the USSR), then the “Parabellum Cal. 9mm” same as in the 2nd version, then “+7,62 mm TT”. The “02” Warsaw Pact parts marks are present.

The likely intent here was to entice the buyer into thinking he was getting a Soviet TT-33, near the end of the time when it was still not simple for the average American to find a firearm made in the USSR. Curiously the Super 12 could fire both 9mm Parabellum and 7.62x25mm Tokarev, via a parts swap-out kit which was included.

On the slide’s right side is a triangle, then the serial number, then “SUPER 12”. A story regarding is, is that during the early 1990s Century Arms in the USA imported a batch of Tokagypts (which themselves had most likely been already exported once out of Hungary), and the ATF decided that “tokagypt” was a general style rather than proper noun and the guns had to be given a legal name, so Super 12 was bestowed. This is not confirmed.

Between 4,000 to 5,000 of these pistols were made. The serial numbers are a whole different scheme, HF____ with a four-digit number.

total production

The whole total is uncertain but including all seven versions, between 30,000 to 33,590 Tokagypts were built.

why the Egyptian contract failed

Considering that the Soviets were already donating small numbers of TT-33s and had the Makarov in production back home, the selection of the Tokagypt to begin with might seem odd.

When WWII ended in 1945, Egypt was rare in the Arab world in being already both fully independent and industrialized, including self-sufficient in small arms ammunition. Prior to the mass influx of Soviet aid, new firearm projects were tailored to this. A good example is the Hakim rifle. This Ag m/42 offshoot was expressly chosen to use Egypt’s mass availability of 7.92 Mauser. Besides ongoing domestic production, Egypt was sitting on a mountain of captured Afrika Korps 7.92 Mauser left behind by the British and a “Free Greek” allotment that became marooned in the country during Greece’s civil war.

(Examples of WWII calibers produced in Cold War-era Egypt: Soviet 7.62x54mm(R) and 7.92x57mm Mauser.)

Along with 7.92 Mauser and .303 British (of which Egypt made so much during the Cold War, it actually was a net exporter), 9mm Parabellum was self-sufficient and thus, the Hungarian pistol fit in nicely as it combined a communist-country buy with locally-made “western” ammo.

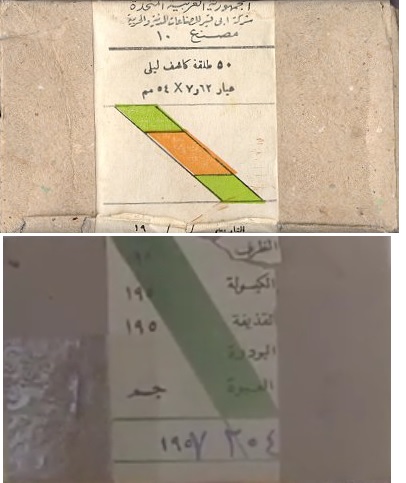

(Egyptian-manufactured 9mm Parabellum.)

The Tokagypt would have seemed to have been the perfect fit, but it was not to be. After 13,250 Tokagypts were delivered of the 30,000 ordered, shipments halted and the contract collapsed. The gun itself never made it to army service, all being instead immediately diverted to the Egyptian National Police.

various theories

Several theories exist as to what happened. One may be true, all may be wrong, or the truth might be a mix. One thing universally agreed upon is that there was nothing wrong with the Tokagypts. They are well built and would have made an excellent military sidearm.

One theory is that the Soviet Union pressured Hungary into cancelling the deal, as it might have viewed it as competition to the so-called “proxy system”. This was essentially when a third world country wanted, for example cheap rifles, from the USSR a Warsaw Pact flunky nation would ship Mosin-Nagants and then in turn receive SKSs from the USSR; later exports would then be filled by those SKSs themselves replaced by AKMs, and so on. This fulfilled two goals: politically it made it appear as if the WP members were legitimate self-determining nations, and, it flushed obsolete kit out of frontline WP divisions.

Almost certainly, the Soviets did not interfere against Hungary’s side of the deal. In no way did the Soviets think like that and to the contrary, just the opposite. If outfits like Omnipol or Technika could wrangle up gun sales denominated in transactable western currencies, that was absolutely fantastic news to Moscow as it put a (tiny) dent in the amount the USSR would remit to buoy up the flailing economies of its satellite allies.

A “reverse” theory is that the Soviet Union pressured Egypt into cancelling the deal. This might be true. The USSR was generous with military aid but at the same time, desired recipient countries to sole-source major buys from the Soviet Union. It is not far-fetched to imagine a Soviet military attache in Cairo telling the Egyptians that even though the Tokagypt buy was “hard cash” through Technika, it would be counted against “proxy system” weaponry allotted from eastern Europe anyways. There is, however, no known evidence of this happening.

Another theory is the simplest, and possibly most likely……the Egyptians didn’t pay. Regarding communist country nation-to-nation arms exports, they were either “fraternal” (free), or, underpriced and via low-interest credit. For the latter (contrary to the impression in the USA during the Cold War) the communists actually did expect to be repaid. They were frequently disappointed. Egypt had a slightly better reputation in Moscow than chronic deadbeats Syria and Iraq, but not by much.

Technika was a whole different story. Its one and only reason to exist was to ingest “capitalist-world” currencies like the dollar, pound, and mark into the encapsulated Hungarian treasury. Simply put, Technika’s job was to make a buck, nothing else. If the Defense Ministry in Budapest volunteered to charitably donate Hungarian army guns to an arab state, fine, that was their concern. For Technika, when accounts receivable went into arrears, boxes stopped leaving the warehouse, end of story.

It isn’t hard to imagine an Egyptian army procurer in Cairo getting used to haggling with the Soviets on a nation-to-nation basis, only to rudely discover that a “hard cash” sale from a parastatal like Technika was a different matter. On the other hand, there exists no known evidence that this is indeed what happened.

A final possibility is that even though there was nothing wrong with the Tokagypts, and even if the Soviets didn’t care, and even if bills were paid; the Egyptians just decided they wanted something else.

(The Helewan pistol.) (photo via GunsInternational website)

Indeed the gun which filled the Tokagypt’s erstwhile role was one that had nothing to do with WWII. After favorable results with a small import batch of Italian Modello 1951s, Maadi in Egypt acquired a production license from Beretta and built the gun as the Helewan. Besides using Egyptian-made 9mm Parabellum ammo, the gun was itself also made in Egypt. The Helewan thus became service-standard in the Egyptian army, and remained so until joined decades later by the Helewan 920 (a license-made Beretta M92-FS) and 9mm Glock 17s.

Surprisingly after all these years, the story of what exactly went sour with the Tokagypt deal in 1958 has never been revealed. It will probably be some time, if ever, before it is. After Technika’s bankruptcy, decades and decades worth of typewritten paper records were thrown loose-page into cardboard boxes and dumped that way onto the Hungary Archives. Outside of firearms historians there frankly isn’t much public interest into sorting them all back out.

the Tokagypt’s forgotten little brother

A “sister deal” to the Tokagypt was the Walam 48, also an adaptation of a WWII pistol. The contract for the 30,000 Tokagypts to the Egyptian army was joined by a 10,000 gun order for Walam pistols for the Egyptian National Police.

The Walam 48 is the “export” version of the FEG M.48, Hungary’s copy of the WWII Walther PP. After WWII, some Walther PP and PPK pistols taken from the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS during the final 1945 battle in the country were incorporated into postwar Hungarian police departments.

In 1946, the Hungarian Interior Ministry ordered a Walther PP clone. Between 1948 and the 1956 uprising, 21,550 were delivered to police, customs, and bank guards plus 450 (stamped “Polgári”) issued as everyday carries to high-ranking communist party apparatchiks, who were unloved by the Hungarian people. The gun was called M.48 but to avoid confusion between the Interior Ministry and army (which called its TT-33 clone the same thing), it was often just called Rendõrségi (police) 48.

The .380ACP Rendõrségi was a true copy to the point of parts interchangeability with WWII German Walthers.

After the uprising, tooling from this project remained and Hungary saw an opportunity for further benefit. The Egyptian police sale was called Walam, a portmanteau of Walther and lamp (Lámpagyár or lighting factory, the early communist euphemism for FEG).

Walam 48s remained chambered in .380ACP but a few changes were incorporated. A new safety was added and the firing pin improved. The gun is ¾” longer. A loaded chamber indicator is on the left side.

(For comparison, a WWII German Walther PP with Third Reich-era markings.) (photo via Tague website)

Because the 13,250 Tokagypts which actually made it to Egypt were themselves immediately diverted to the Egyptian National Police, there was no need for the Walam 48. Out of the 10,000 ordered about 6,900 (or even less) were actually delivered. The rest were made available for sale elsewhere.

(Probably the whole 10,000 had already been started when the contract collapsed. This is an undelivered one lacking the Egyptian symbol sold by Technika. There are also “sterile Walams” with no markings at all.)

how Tokagypts came west

After the Egyptian contract died, Technika began searching for a new home for the Tokagypt. The gun found a niche in the West German civilian market (1960s / 1970s West German gun laws being much more accommodating than 2020s Germany).

This is also how the gun found a more sinister niche with terrorists and criminals, and also how much of the Tokagypt’s history becomes cloudy.

(photo via Maryland Shooters)

Above is a 1st version Tokagypt. The “Heart of Hungary” underneath the slide catch notch is actually supposed to be an aiming-reticle with the letter I in the middle. On Cold War Hungarian guns, it was often struck with a worn die and/or in a place that truncates the top, creating a sort of heart shape or half circle with what looks like an upside-down T.

Above the trigger, the “N” is the post-1952 Bundesadler in West Germany signifying nitrocellulose proofmarked. Regarding the Tokagypt, a minority but extant number of arms dealing experts feels that at least on some, this may have been counterfeited in Hungary to dodge a layer of West German government. This is uncertain and maybe fanciful. The meaning of “65” is unknown, typically on a West German-proofmarked pistol it is a two letter code indicating date of manufacture. The squiggly line is actually an elk antler laid sideways, indicating that the Ulm proofhouse issued the “N”. The antler on this Tokagypt appears as an exceptionally low quality strike.

The “02” is missing from the slide catch indicating an aftermarket part, or, that it was intentionally removed when the gun was blued.

“HEGE” on the triggerguard is Georg Hebsacker’s arms dealing company in Schwäbisch Hall, Hege-Waffen. During the Cold War, one of Hege-Waffen’s niches was firearms from the other side of the Iron Curtain, especially Hungary.

(A pegasus was also used sometimes by Hege-Waffen.)

Hege-Waffen, along with Albin Wahl also in West Germany, was one of the “original” counterparties to Technika in bringing Tokagypts west.

On versions with “West Germany”, this stamp was likely done in Hungary, and there is every possibility it was done to obscure the COO (country-of-origin). Many (not all, but, including the USA) countries determine import eligibility by original COO, not country of re-export. Certainly in-depth research would reveal the truth but facing a customs official not familiar with the tens of thousands of handgun types worldwide, there was decent odds in the 1970s of whatever markings being stamped onto the pistol would be taken at face value. Obviously, a gun seeming to come from West Germany would carry much more resale potential (and thus, value) to a dealer than one blatantly from a Warsaw Pact member.

On the Firebirds this is especially probable as “West-Germany” was never spelled hyphenated in English by West Germans.

Tokagypts in the underworld

Especially in Europe, the Tokagypt is known as the “terrorist’s delight”. Given this WWII-derivative gun’s obscurity, it had quite a disproportionate representation in Cold War-era violence.

“Patient Zero” for this was probably the West German far-left terrorist Andreas Baader, co-founder of the Baader-Meinhof Gang aka Red Army Faction. In 1970, Baader was in Jordan at a training camp of the Palestinian Fatah organization, and was trained on use of firearms including the Tokagypt, which he loved. From then on Tokagypts (often of the Firebird variety) were greatly associated with the Baader-Meinhof Gang in West Germany.

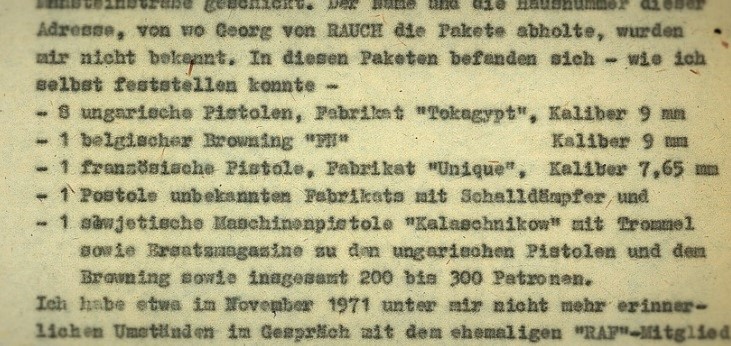

This snippet is from a Stasi (East German secret police) interrogation of Michael Baumann, aka “Bommi”, a member of the “2.Juni” left-wing group who had fled to Czechoslovakia and then in 1973 crossed into East Germany with forged documents.

While the East Germans were clandestinely supporting the Baader-Meinhof Gang (which was separate from 2.Juni but allied with it), they were uncertain of the Gang’s inner workings and also suspicious of 2.Juni. So the arrest of Baumann was a good opportunity to study both.

The page relates to the firepower which one cell of the Baader-Meinhof Gang had during the early 1970s: eight Tokagypts, one Browning Hi-Power, one WWII French Mle.1935S (aka .32ACP Unique), one pistol which Baumann couldn’t identify, and one AK-47 assault rifle along with spare magazines for the Tokagypts and 200 – 300 rounds of ammo.

For reasons still unclear (perhaps, simply because the group’s founder liked it so much) Tokagypts / Firebirds became synonymous with the Baader-Meinhof Gang. One member of the group, Rolf Pohle, specialized in buying Tokagypts using forged IDs and fake gun permits. He eventually pushed his luck too far and a gun store owner notified police of the suspicious interest in this particular gun. The Baader-Meinhof Gang made use of its Tokagypts, including a 1972 drive-by shooting against West German police.

Functionally, there seems to be nothing especially unique about the Tokagypt to make it so appealing to 1970s and 1980s terror groups. It was very well built, but so were a lot of other semi-auto 9mm handguns. The WWII Tokarev shape was not particularly concealable either. None the less, the Tokagypt spread to other 1970s / 1980s terror organizations in western Europe: Basque separatists in Spain, far-left groups in Portugal, and so on. The gun’s reputation in these circles seemed to just feed itself, with no real other explanation.

The above snippet is a 1979 American intelligence report on far-left groups in Italy, with a focus on how the “Red Brigades” organization was replacing WWII guns with AK-47s and Tokagypts. This document was declassified in 2007.

The Tokagypt (and surprisingly also, the Walam) was present in middle eastern terror groups as well.

(official CIA photo, declassified in 2011)

The Walam 48 above (modified with a threaded extended barrel) was captured by the IDF from a Palestinian group in Lebanon during Israel’s 1982 invasion of that country. As passed on from the Mossad to the CIA, the gun offered insights into how arms dealers interacted with arab militants.

The gun, a so-called “sterile Walam” was post-production marked “GSM MAUSER OBERAUDORF GERMANY”. For starters, the town’s name is Oberndorf not “Oberaudorf”. Secondly, Mauser never had any involvement with Walther. During the Third Reich era, the Mauser-Werke in Oberndorf made the Wehrmacht’s M-1914 and Kriegsmarine’s M-1934 pistols; neither of which remotely looks like a Walam.

Almost certainly this was the handiwork of an arms dealing middleman. In the arab world, German guns – especially of WWII vintage – had a reputation for high quality and the seller no doubt saw “value-added” opportunity in the inscription, to hike the price to a less-informed Palestinian buyer.

Tokagypts themselves appeared as well, both in Lebanon’s 1980s strife and elsewhere thereafter.

(photo via Calibre Obscura website)

This spread was captured from an ISIS bomb workshop in Syria in June 2019. The pistol upper right, closest to the blue IED barrel, is a Tokagypt with an extended threaded barrel. Also of WWII interest, the gun below it is a Mle. 1922, the French army version of the FN 10/22 used during the 1940 defeat. It was probably left behind by the Vichy troops in Syria decades ago now.

(A Tokagypt recovered in Iraq during 2019. It had originally been imported into West Germany by Albin Wahl during the Cold War.)

One place where the Tokagypt has no bad reputation is the USA. It is extremely rare to see the gun associated with crime in the country. Curiously, as recently as 2019, the evidence coding used by some American police departments still lists the Tokagypt’s manufacturer as Ferunion, the Cold War-era Hungarian sales front.

To bring the story to a close, Egypt is worth a final mention. In 1958, as mentioned, the 13,250 delivered Tokagypts were dumped off onto the Egyptian National Police. They were certainly needed, as even a decade-plus after WWII, the force still had a motley assortment of pre-WWII Webleys, Colt .38s, and other six-shooters.

Law enforcement in Egypt is multilayered and includes the National Police, State Security, niche departments like the tourism police, and finally local municipal police. When the National Police replaced the Tokagypts with CZ-75s and Glocks, they filtered down to the lower levels.

During the Mubarak era these departments had issues with corruption and a number of “toekjepts” as they are pronounced locally, are now on the wrong side of the law in Egypt too.

From el-Balad newspaper in January 2013, the underlined passage describes “Tokagypt 9mm handgun serial 7758” being recovered from a crime scene. Tokagypts were also used in a 2010 carjacking in Nasr City and other crimes.

The local police in Uzbakeya, a district of Cairo, was still carrying Tokagypts in the late 2010s.

postscript

Tokarevs (and even WWII TT-33s) serve on worldwide but Technika no longer exists. After communism ended Hungary still needed dollars; but now with Hungarian banks welcomed internationally there was no need for weird clandestine ways to obtain “western” currencies. Overall the world was flooded with ex-Warsaw Pact weaponry in the 1990s and it was hard to profitably deal in the same. This wasn’t made any easier by a Hungarian court blocking an attempt to incorporate Technika as a normal company. The new democratic government restricted arms exports (governmental, commercial, and private) to a handful of customs posts. Maybe the last nail in the coffin was a scandalous 1994 affair to sell guns through Panamanian and Ukrainian front companies into the violent breakup of Yugoslavia. Technika fully went bankrupt in 1999.

FEG was, by the turn of the millennium, considered a “distressed defense company” in the world scene. In 2004 it effectively exited the military arms market and by 2010 was almost bankrupt, being bought out and converted fully to a heating and air conditioning company.

Tokagypts appear from time to time in the USA’s civilian market, with major batches having been imported by Century Arms and SSME. They are generally inexpensive, usually less than $400. The Tokagypt has been on the ATF’s “Curios & Relics” list for at least three decades now; not surprising considering the gun’s curious path from the WWII Tokarev.

(This holster is not the original Egyptian design but is very often seen with Tokagypts today, like this one imported into the USA by SSME.) (photo via Empire Arms)

Hey man! very good write up! We’ve got a couple more HD photographs of the Tokagypt and the Walam 48, in addition to Egyptian 9mm if you are interested in using them here.

LikeLike

Thank you, love your website BTW; all-around excellent!

LikeLiked by 2 people

You’re too kind sir! Really appreciate those compliments, and right back at yours as well!

We’d love to email you as well! silahreport@gmail.com

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great research. Interesting read, as always.

LikeLiked by 2 people

TT-30 and TT-33 are not blow back operation. They use Browning Tilt Barrel lock system.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello,

Very interesting read, as always 🙂

Possible to give the full Warsaw Pact’s internal code for weapon, if you have them ?

I’m unable to find it anywhere 😦

Thanks !

LikeLiked by 1 person

I actually have not been able to find a full, trustworthy list myself. I have seen Polish-made Makarovs with both “1” and “4”. I was once told once that “1” was the USSR but separately told that the Soviet Union had no number as it was assumed to be the default maker of anything. I have seen a lot of Bulgarian-made guns with “10” but that also doesnt completely make sense as at its peak, the WP only had 8 members.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The code is the factory’s code within the country, not the country code within the Warsaw Pact or even the factory code within the Warsaw Pact as a whole.

You see an 11 in an oval for Poland’s FB Radom on stuff like the M44 Mosin, various AK variants, P64, P83, and probably the PM63 too. Poland made no Makarovs. Polish ammo turns up with an oval 21 code too.

Bulgaria’s Arsenal at Kazanlak used a Circle 10. You see Bulgarian AKs, Makarovs, and ammo with the Circle 10. There are also Circle 21 and 25 on AK mags, but I’m not sure which factories those were.

Hungarian ammo also has a 21, for some factory in Hungary that was not 02 (FEG).

Soviet small arms were marked with the factory symbol, no code. The ammo was coded though, like 188 for Novosibirsk, 3 for Ulyanovsk, and 711 for Klimovsk.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As always, first-rate research and an extremely impressive article! The perched eagle logo is the insignia of the Egyptian Police and Interior Ministry during the 1950s. They continue to use a very similar insignia (with the eagle’s wings outstretched upwards) to this day.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The rifle the freedom fighter has is a K98k with bottom sling swivels added, not a 43M. Look at the location of the bolt handle and the shape bolt shroud assembly (the rear pieces). It’s distinctly a Mauser 98 action.

LikeLiked by 1 person