Since starting wwiiafterwwii, numerous people have contacted me requesting I write something on this topic. This is understandable as the M1 Garand remains one of the most popular rifles of all time, and there is a high degree of interest with American readers (and to my surprise, some readers in Vietnam as well) in the Vietnam War.

Other discussions on this topic usually end up in a fairly simplistic debate of “yes there were Garands used in Vietnam” or “no they were all gone by then” so hopefully this is of some value.

(South Vietnamese soldiers with M1 Garands on patrol during 1963.)

(A member of Vietnam’s DQTV militia takes aim with a M1 Garand in December 2018.)

(The legendary M1 Garand of WWII was a semi-automatic rifle which fired the .30-06 Springfield cartridge (2,800fps muzzle velocity) from a 8-round internal en bloc. It’s effective range was 500 yards. It was tremendously successful during WWII.)

the beginning

The first “local” army after WWII was the Cochin & Annamite Militia, a force recruited by France. It was equipped with whatever was available; typically Stens and Enfields donated by the British, guns of the former Vichy garrison, ex-Wehrmacht firearms shipped by France from Europe, and increasingly, American WWII guns.

On 8 March 1949, the Vietnam National Army (or by it’s French acronym, ANV) was created to replace various militias. Nominally led by an ethnic Vietnamese general, it served as the “local” contingent alongside the French Foreign Legion and other French units fighting the Indochina War.

(ANV soldiers parade in Hanoi – the future North Vietnamese capital – during 1951. They are armed with MAS-36 rifles and Modèle 24/29 machine guns, both of WWII French vintage.)

(1950s ANV soldiers examine an old Vickers machine gun, presumably left behind by the British in 1946 after their short post-WWII stay in Indochina.)

The ANV at first had a goal of standardizing on WWII-era French weapons, however as it turned out these were joined by postwar French guns, continued shipments of 98ks and MP-40s from Europe, and increasingly American-made WWII guns. Of these, the most common were the Thompson submachine gun family. The first Vietnamese M1 Garands arrived during this timeframe, coming from the USA’s transfers to France, which received 198,000 during and after WWII.

For it’s part, both the opposing Viet Minh were also heavily invested in WWII guns, basically everything under the sun: Mosin-Nagants from the USSR, ex-Wehrmacht 98ks and MP-40s via both the French and the Soviets, Mausers from China, MAS-36s captured from the French, British Enfields from sources unknown, Arisakas abandoned by the Imperial Japanese Army in 1945, and an ever-increasing number of captured American-made WWII guns: M3 Grease Guns, M1 Thompsons, M1 carbines, and even a few Garands.

(Viet Cong members with a Gongxian on a bamboo AA mount. Manufactured in China during WWII, this 7.92mm machine gun was a copy of the Czechoslovak vz.26. After Mao’s communists won the Chinese Civil War in 1949, odd WWII-era arms of the nationalists were dumped off into North Vietnam. By the 1960s, a gun like this was obsolete but could still shoot down a Huey.)

In July 1954, France began it’s exit from Indochina and ANV units were pulled south of the 17th Parallel, the line which was supposed to have been a temporary division of the country but became the DMZ. In October 1955, with what would become South Vietnam coalescing, the ANV was renamed the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), effective 30 December 1955.

(map via National Geographic magazine)

M1 Garands in the ARVN

Less Garands already in-country from the ANV era, major shipments of M1 Garands to the ARVN started in 1963 and ran off and on for the remainder of the USA’s involvement in the conflict. Below is a year-by-year table of M1 Garand deliveries.

The reason for some of the small lot sizes in uncertain. These may have been paperwork maneuvers to square up previous shipments, or, may have been honest accounting of very tiny transfers. The 1967 shipments went to the USA’s Military Assistance Advisory Group for redistribution; one might assume this was to prevent corruption and incompetence by ARVN generals.

As shown in the table, warehoused M1 Garands were drawn from both the US Army and the Department of the Navy, which also included US Marine Corps Garands, but excluded US Coast Guard examples, as that branch was part of the Department of the Treasury at the time. No US Air Force Garands went to the ARVN.

Legal authority for M1 Garand transfers to South Vietnam was through Section 501 of the Military Assistance Program (MAP), a law passed in 1961. This facilitated the rifles as no-cost loans of indefinite duration, with the United States retaining first option on reclaiming the guns when South Vietnam no longer wanted them (this of course became moot when the country collapsed in 1975). Section 505 of MAP prohibited South Vietnam from reselling the Garands; of which they were seemingly in no position to do anyways.

Garands were only a small part of MAP aid given to South Vietnam, which ranged from bayonets to warplanes. Between the time the ARVN was formed in 1955 and it’s extinction 20 years later, the USA loaned $14.78 billion worth of weapons to the country ($61 billion in 2019 dollars) via MAP. Naturally this is dwarfed by the USA’s own spending on the Vietnam War, which was roughly the equivalent of $1.1 trillion in 2019 dollars. The bulk of the MAP gear came during operation “Enhance”, part of President Nixon’s “Vietnamization” policy in 1972 – 1973, which accelerated arms deliveries. The above report was presented to President Carter in 1978.

MAP Garand transfers were organized by the multi-services Pacific Command (PACOM) at USMC Camp Smith, HI. Rifles taken from various points in the United States were consolidated at ports in California, and usually sent via merchant ship to Saigon or Cam Ranh Bay by way of Japan or the Philippines.

The Garands supplied to South Vietnam were not segregated by their original manufacturer or production year; all were mixed together. As the M1s transferred out of American custody, each entire lot was reassigned one new NATO stock number (NSN). For example the large first lot in 1963 was assigned the NSN 1005-00-674-1425. This number, which still exists in the NSN database in 2019, has a description of “Rifle, Caliber .30” and a listed weight of 9,999 lbs. The manufacturer is listed as “United States Army” with a mailing address of Rock Island Arsenal.

(With M1 Garand deliveries flowing, the ARVN could flush out obsolete holdings. In October 1969, an auction of 200,000 old weapons was held, with scrappers and arms dealers both eligible to bid. Shown here are a Mle. 1892/M.16 cavalry carbine and a Berthier rifle; both holdovers from the French era.)

in ARVN service

M1 Garands naturally replaced any legacy MAS-36s or other WWII bolt-actions left over from the Indochina War, in addition to some M1/M2 carbines being inappropriately (in American eyes) used as standard infantry rifles. However by large, they replaced nothing as most were assigned to completely new ARVN units which were being rapidly recruited as South Vietnam’s army expanded in size.

(South Vietnamese troops pose with M1 Garands in July 1961.) (photo via Life magazine)

By no means was the Garand the only WWII firearm in daily ARVN use during the 1960s and early 1970s. The M1/M2 carbine, the M1911 pistol, the Thompson family (M1928, M1, and M1A1), the M1918 BAR, and the M1919 and M2 Browning machine guns were all in service.

(A South Vietnamese unit poses with a UH-1 Iroquois helicopter. All firearms are of WWII vintage: the soldier taking aim has a M1 Garand rifle, the others Tommyguns or M1 carbines.)

(This 1965 photo shows ARVN troops armed with M1 Garands, M1918 BARs, and M1 Thompsons – all WWII guns.) (photo via Life magazine)

(With the M1 Garand, the ARVN used both WWII-surplus M1905 and M1 bayonets, and the M5A1 shown above. The M5A1 entered American service during the Korean War. This plastic-handled design was basically a M3 combat knife modified for bayonet use.) (photo via warrelics.eu website)

(A South Vietnamese soldier in 1968 equipped with a M1 Thompson, Mk2 pineapple grenade, and M1 pot helmet; WWII items.) (photo via Life magazine)

(The M1 pot was standard headgear in the ARVN it’s entire existence. This one is marked in the late-1960s style of military police.)

The M1/M2 carbine was most popular as the ARVN viewed it’s lesser recoil and lighter weight as being superior to anything else (including the M1 Garand) in their perception, prior to M16s being available. Some South Vietnamese troops were loathe to exchange their carbines for Garands, even though on paper the M1 Garand was clearly a superior battlefield asset. Before large-scale transfers of M16s started, this perception was occasionally a point of contention with American advisors.

(A paratrooper of the ARVN with slung M1 carbine and a captured RPD, a Soviet-made light machine gun of Cold War vintage.)

(The “other side” appreciated the M1 carbine as much as the ARVN. This 1971 photo shows a female Viet Cong on the Ho Chi Minh Trail armed with one.)

The virtues of the M1 Garand in Vietnam were much as they had been during WWII: it was rugged, reliable, accurate, and the .30-06 Springfield had respectable stopping power and penetration through jungle foliage. By the mid-1960s, it’s perceived vices were lack of full-auto as the AK-47 became more common on the battlefield, and the rifle’s physical size, as discussed further below.

(A South Vietnamese soldier with WWII M1 Garand and Mk2 pineapple grenade during the 1960s.)

(Cadets of South Vietnam’s Military Academy pass in review with M1 Garands. Whatever it’s other hardships, the ARVN was never short of pageantry.)

(This photo shows an American advisor with a very early model of the AR-15 (note no forward assist and original-pattern mag) while his South Vietnamese partners carry M1 Garands.)

(Rangers of the ARVN armed with M1 Garands in 1961.) (photo via Life magazine)

(ARVN officer candidates train with M1 Garands.)

(ARVN paratroopers with M1 Garands pose with MPs with M1 carbines near Phan Thiet in 1968.) (photo via ARVN Veterans Association)

(ARVN Rangers train with a M1918 BAR and M1 Garands during the 1960s.)

(A Ranger of the ARVN strikes a pose with sandals, sunglasses, civilian transistor radio, and nón lá hat. Rangers were tremendously respected in the ARVN and generally allowed to do or dress as they pleased. The M42 “duck hunter” camouflage originated in the US Marine Corps during WWII. It was popular with US Army SpecOps personnel during the Vietnam War, and the same in the ARVN. This Ranger is armed with a M1911A1, the infantry behind him M1 Garands.)

the “physical stature” issue

One of the concerns regarding the use of the M1 Garand in Vietnam was that, on average, South Vietnamese recruits were shorter and smaller than their American counterparts had been during WWII. It did not help that although the legal draft age in South Vietnam was 18, rural teenagers two or even three years below were sometimes conscripted.

(Young ARVN soldier with M1 Garand and four en blocs in 1966.)

Like many things, this supposition was probably a mixture of fact and imagination. The M1 Garand was of average length & weight by WWII rifle standards, and maybe a bit long for soldiers with short arms. Likewise the .30-06’s recoil was not punishing but not mild either. On the other hand, when Japan rearmed after WWII it selected the M1 Garand as it’s first service standard rifle without problems, despite the fact that the same concerns had been voiced in relation to the average build of JGSDF recruits.

The Pentagon’s long-running (1961 – 1974) “Agile” project, which originally sought to refine skills, technology, and tactics for third-world allies to fight in extremely rural areas, was interested in this issue.

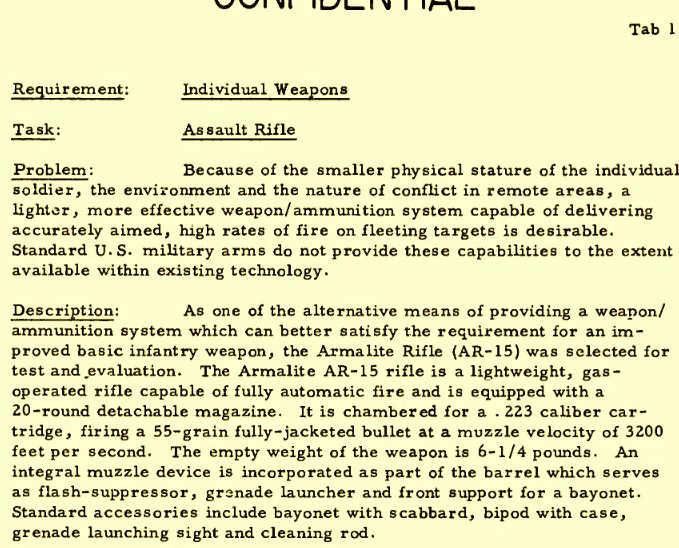

One recommendation of “Agile” was to consider converting the ARVN from the M1 Garand to Armalite’s then-new AR-15 rifle, which was eventually done in the form of the M16.

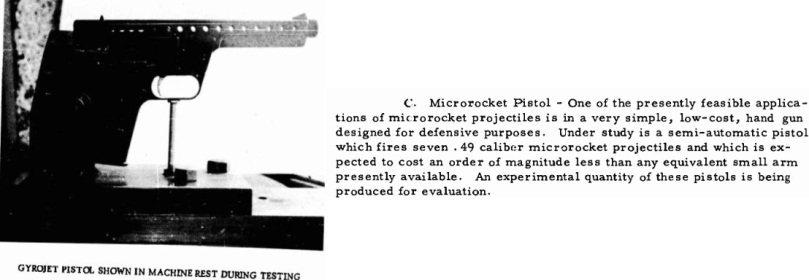

“Agile”s other ideas descended in levels of seriousness after that, starting with a suggestion to convert from the Garand to Eugene Stoner’s modular “63” weapon system (25 of which were made by Cadillac Gage for the ARVN) all the way down to a suggestion to adopt the Gyrojet system; an idea thankfully not taken beyond basic concept phase.

“Kalishnikov vs Garand” in Vietnam

In popular culture, the Vietnam War is portrayed as the classic match between the M16 and AK-47, however the reality was more complicated than that. In the early phases of the war, probably all the way up to the Tet Offensive in 1968, the Viet Cong used any imaginable firearm; largely SKSs and Mosin-Nagants but with a liberal dose of 98ks, MAS-36s, M1 carbines, MAT-49s, PPSh-41s, MP-40s, and AK-47/AKMs; while the de jure North Vietnamese army used a mixture of SKSs and AK-47s/AKMs – continuously shifting to the latter pair. After Tet, AKs became predominate.

Likewise, before 1968 the ARVN was equipped almost exclusively with WWII-era firearms, thereafter rapidly going on par with the US Army’s current types.

(ARVN soldiers with M1s in the 1960s.)

(Viet Cong guns captured during 1967’s operation “Cedar Falls”; represented are the M1 carbine, PPSh-41, M1 Thompson, M3 Grease Gun, MAT-49, RPG-7, and come civilian guns. Of the military arms, all but the MAT and rocket launchers are WWII-vintage. Some look as if they hadn’t been serviced since 1945.)

The M1 Garand was superior to any WWII-vintage bolt-action weapon in Vietnam, and to the post-WWII SKS as well. Compared to the AK-47, the Garand was of equal weight and ruggedness. While the most cited difference was the AK’s full-auto capability; to the ARVN other factors were more important. A loaded AKM had equal mass to a loaded M1, but, held 30 rounds to the Garand’s 8. While of equal loaded weight, the AK was 10″ shorter; making it not only easier for troops of modest stature to hold, but also less cumbersome in the jungle.

The weights of cartridge mattered as well. In what are called “fire units” (a military logistics term); an 80-round M1 Garand fire unit weighed 119½ lbs in ten articles (nine .30-06 en blocs + a loaded rifle), while a 90-round AK-47 fire unit weighed just 77 lbs in three articles (two preloaded 7.62mm mags + a loaded rifle). Thus the AK was superior in that regard; especially when considering the nature of most North vs South encounters; which were usually brief affairs decided by which side laid the most lead on the other in the most rapid timeframe; not classical infantry tactics.

One clear advantage the Garand held over the AK-47 was accuracy, but for the ARVN this was degraded by the abysmal marksmanship of it’s average soldier; being rushed through boot camp as cheaply as possible and then sent straight into combat.

Any M1 Garand could be fitted with the M7 rifle-grenade launching kit, which was an advantage compared to the communists, who typically assigned a dedicated RPG-7 troop plus dedicated ammo-bearer for this task.

(1964 selectees at the ARVN’s NCO course, training with the Garand’s M7 kit.)

As the ARVN received increased numbers of M79 40mm grenade guns during the 1960s, this advantage faded as well, as squads followed the American example and patrolled with a dedicated “thumper”.

replacement of the M1 Garand in the ARVN

(1963 document advocating the AR-15 as a new standard rifle for the ARVN.)

In 1962, South Vietnam took delivery of 1,000 AR-15s (the original Armalite design). This was part of a DARPA (the Pentagon’s research arm) study as to the weapon’s feasibility for eventual American use. The results of real-world use of the rifle was monitored by American defense advisors in South Vietnam and reported as “highly favorable”.

Besides the battlefield advantages, there was a strong desire to standardize the American and South Vietnamese armies as far as ammunition. With the American changeover to M16 / 5.56 NATO starting in 1964, there was strong momentum for ARVN units to follow suit.

(American soldiers with M16s meet up with a South Vietnamese armored cavalry unit still equipped with M1 Garands.)

While the need to replace the M1 Garand was more or less decided, actually doing so was another matter and deliveries of the M16 (initially, the notoriously unchromed pre-A1 versions) were slow and sporadic. Only in May 1968, after the Tet Offensive had started, President Johnson released 100,000 M16s for South Vietnam.

(Depending on who is to be believed, American Gen. William Westmoreland either sped up or stalled South Vietnam’s adoption of the M16. Here he reviews a ARVN pathfinder unit armed with M1 Garands.)

Oddly enough by late 1968, a few months after final M1 Garand deliveries of any note were made, the ARVN’s first-tier combat divisions had already converted to M16s. Thus the ARVN’s rifle progression (and associated teething troubles) was rapid: MAS-36 to M1 to M16, in only about a decade and a half.

Just as in the US Army, the ARVN’s changeover from WWII M1 Garand to modern M16 was not “flipping a switch” but rather gradual. Ranger and airborne units were the first to get it, followed by infantry, then finally comms, MP, and other units. During the late 1960s it was common to see ARVN units of mixed M1 Garand / M16 composition.

(ARVN radioman with M1 Garand.)

(Naturally the South Vietnamese navy was slower to transition than the army. Here, US Navy Adm. Thomas Moorer reviews a South Vietnamese honor guard with M1 Garands.)

By 1973, the changeover was complete and most frontline combat units of the ARVN had standardized on the M16.

use by ROK forces

Often forgotten is that South Korea participated in the war. A total of 300,000 South Korean (ROK) soldiers rotated through Vietnam; usually at 40,000 – 45,000 strength at any given time. The ROK Army 9th “White Horse” division and ROK Marine Corps 2nd “Dragons” brigade were the main elements.

(A ROK marine in South Vietnam armed with M1 Garand during 1966.)

(South Korean soldier with M1 Garand in South Vietnam.) (photo via Asia Economy Daily newspaper)

For South Korea, there was a desire to standardize with the US Army and ARVN as they changed rifles, however the situation was more complex as it’s own homeland had a “hot” northern border to defend. During the late 1960s, there was a brief interlude where the M1 Garand, M14, and M16 were simultaneously being used.

use (or, non-use) by American forces

There was no official unit-level use of standard (non-sniper) M1 Garands by American forces in South Vietnam after 1963, which is quite certainly not the same as guaranteeing that none whatsoever happened.

(The US Army expected it’s next war to be a short high-intensity conflict with the Warsaw Pact in Europe. As involvement in Vietnam deepened, new tactics had to quickly be developed. This early-1960s photo shows a COIN (counter-insurgency) exercise inside the USA. Soldiers armed with M1 Garands examine fallen rebels, played by fellow soldiers.)

The M14 officially replaced the M1 Garand as the US Army’s service-standard infantry rifle in 1957. In a behemoth the size of the Cold War-era American army, this was not just “flipping a switch”, and the changeover was protracted. It was not until the start of 1965 that the ADCC (active-duty combat component) was fully converted; here with ADCC meaning active-duty (not Reserve or National Guard) divisions intended for actual combat; those typically being infantry, air cavalry, armored, MP, and airborne. Even within these divisions, subunits such as HQ companies, logistics, and the such, retained M1 Garands until sufficient M14s were available.

In 1964 (actually, even before the M1-to-M14 change itself being completed), the M16 began to enter US Army service, following the same general path. Throughout the late 1960s, into the 1970s and end of the Vietnam War, M14s then fell down the food chain and equipped National Guard, reserve, and non-ADCC units; often (but not always) replacing M1 Garands.

Thus the US Army’s progression from the WWII-era M1 Garand through M14 to the modern M16 was not linear; with subunits in some US Army divisions retaining M14s well past the end of the Vietnam War, and some subunits converting directly from M1 Garands to M16s during the conflict.

(American instructors train South Vietnamese troops on the Garand in 1964.)

In Vietnam, this meant that the Garand was absent. The US Army accelerated the use of the M16 as much as possible, so that by 1967 it was quite clearly the predominate type in-country.

An irony of the war was that in the US Army, other WWII firearms – the M3 Grease Gun, M1 Thompson, M1 carbine, M1897 shotgun, and even M1918 BAR – were decently represented in-country….just not the M1 Garand.

In the American defense establishment, the US Marine Corps is part of the Navy department and it’s rifle program was separate from the US Army’s. Some USMC units very early in the war may have still had Garands, but not to any appreciable extent. For example the USMC 9th Expeditionary Brigade was already equipped fully with M14s when it landed at Da Nang in 1965.

(The caption on this March 1965 photo is probably wrong and the men with Garands are likely US Navy sailors of a beachmaster team. All USMC amphibious units in Vietnam had already fully converted to the M14 by then.) (UPI photo)

(The USMC’s final changeover from M14 to M16 was more protracted than the US Army’s. Taken during the 1968 Hue battle, this photo shows Marines using the M14 and M16 side-by-side.)

Generally speaking, the standard (non-sniper) version of the M1 Garand simply did not see American use in the conflict.

sniper versions of the Garand

While the American military did not use the basic version, it certainly did employ the sniper versions of the M1 during the war, as did the ARVN.

(Sniper versions of the Garand along with a standard model.) (photo via National Rifle Association)

Both the M1C and M1D versions saw use in Vietnam. There were two runs of sniper Garands, the main one during the final two years of WWII and then a supplementary build during the Korean War. American forces in Vietnam used the sniper Garands until sufficient M40A1s were available. For the ARVN, this was it’s only sniper rifle it’s entire existence.

use by “the other side”

The communists (regular North Vietnamese army and the Viet Cong) were not about to turn their noses up at any captured M1 Garand, especially in the earlier and middle (basically before 1968) parts of the war. Similar to the ARVN, the communists also considered the M1 Garand less-preferable than the lighter M1/M2 carbine, or full-auto American WWII guns like the M3 or Thompson.

(North Vietnam published a series of pamphlets for distribution to the Viet Cong on use of captured American-made weapons. This one describes maintenance of the M1 Garand.) (photo via enemymilitaria website)

(A soldier of the ARVN with M16 guards captured Viet Cong weapons after the Tet Offensive. Most are combloc gear but there are two M16s and in the center, a M1 Garand.)

the end

With the “Vietnamization” policy at the end of the 1960s and curtailment of American involvement in the early 1970s, South Vietnam was in a precarious position, now without the American air and ground support it had leaned on throughout the war; and with the North still largely on a war footing. The year 1973 marked the final deliveries of any M1 Garands to South Vietnam; by which time the M1 had already largely been supplanted in first-tier use by the M16.

Despite it’s predicament, the speed with which South Vietnam collapsed in 1975 surprised military observers worldwide. In early March 1975, the North decided to undertake a limited offensive in the central highlands region, both to gain territory and more importantly, to see how far they could push their luck before the United States intervened again. But there was to be no more American involvement and by mid-March, the communists held the northern inland quarter of the country and decided to just keep going. Having already overstretched the ARVN, which was weaker than it had been five years previous, South Vietnam’s government made a fateful choice to retreat completely from the upper half of the country, basically anything beyond Cam Ranh Bay.

This “temporary consolidation” turned into a rout. By month’s end, Da Nang and Hue had fallen. By mid-April North Vietnamese troops were approaching Saigon, and on 29 April the USA evacuated it’s embassy.

Contrary to the sometimes-portrayal today, the ARVN did not just buckle and give up at the end. Many ARVN units fought with great courage. One battle stands out; at Xuan Loc during the second and third weeks of April, remnants of the ARVN 18th Division along with what remained of the South’s air force, held off and briefly even pushed back an entire North Vietnamese corps. But it was all too little, too late. The ARVN’s rank-and-file was let down by squabbling generals, a clueless government in Saigon, and years of neglect beforehand.

On 30 April 1975 Saigon was overrun and that was the end of South Vietnam and the end of the Vietnam War.

the Thuong Tiec statue

One of the more visible artistic renderings of the M1 Garand in South Vietnam was at the Binh An National Cemetery; the country’s rough equivalent of what Arlington is to the American military. At the time the country collapsed, the cemetery contained graves of about 16,000 fallen ARVN troops, a tall concrete obelisk monument, South Vietnam’s Tomb Of The Unknown Soldier, and the Thuong Tiec statue.

(The Thuong Tiec (mourning) statue. The pagoda on the hill behind covered the ARVN’s unknown soldier.) (photo via vnafmamn.com website)

The bronze statue showed a seated ARVN soldier in M1 pot helmet with a M1 Garand rifle. It was sculpted by Nguyen Thanh Thu, who said he was inspired by seeing a battle-weary ARVN soldier having an imaginary conversation with fallen buddies. It was installed at the cemetery in 1971.

When South Vietnam fell in 1975, the statue was toppled over by North Vietnamese troops.

During the late 1970s, the unified government closed the cemetery, encircling it with a cinderblock wall with signs insulting the buried ARVN troops. The statue’s base was bulldozed and a guardpost erected on the spot to prevent any commemoration.

During the 1980s, an American veteran of the war managed to get inside and filmed the cemetery’s condition; it was guarded with restricted access, completely overgrown and being used to graze cattle, with a factory built over some of the graves. Many tombstones had been vandalized. The ARVN’s Tomb Of The Unknown was pried open, empty, and desecrated. By contrast the nearby official Vietnamese military cemetery, which opened two years after the war ended, was immaculate and well-maintained.

During the 1990s, the Vietnamese government started to allow widows and families to visit individual graves again. In 2006, the Vietnamese police stopped guarding the cemetery and allowed general access, however any ceremonies are still prohibited, and no funds are allocated to maintaining the graves, which must be done by families.

Discussion of the ARVN is both a cultural and legal taboo in modern Vietnam – quite different than the way modern Americans openly discuss the Confederate army; or modern Nigerians, Biafra’s.

FATE OF THE ARVN’s M1 GARANDS

The victorious North, now governing a reunified country, inherited intact an unimaginable haul of American-made weapons in 1975. In all post-WWII military history there was nothing even remotely close to this event. The only vague parallel was in 1990 when reunified Germany inherited the East German military, but that was under much different circumstances.

(A Northrop F-5 fighter inherited from the defunct South’s air force in 1975, ready for a mission in 1979.)

The grand prize was 114 fighter jets; followed by about 800 other aircraft, 550 tanks, 1,300 artillery pieces, the bulk of the South’s navy, thousands of APCs, trucks, MUTTs, and hundreds of thousands of firearms with millions of rounds of ammunition.

(Taken on 1 May 1975, this photo shows a pile of M16s, M60s, and M1919s of the defeated ARVN.) (Associated Press photo)

This bonanza of free weaponry would not all be usable. In late 1975 / early 1976 the Vietnamese had to consider several factors: ♦What they actually needed ♦Which American-made gear compared favorably to Soviet-made systems already in use ♦What could keep going long-term.

The last factor was most important. There would never be further American spare parts or ammunition support; so going forward these would need to either be replicated locally, or, obtained on the worldwide arms black market.

(One source of spare parts was to strip one item to keep another two or three going a while longer. Here is a graveyard of stripped ex-South Vietnamese aircraft.)

For the Vietnamese, choices had to be made as to what would be kept and what wouldn’t. For example, money spent to reverse-engineer parts for a WWII-era warship could not then be spent on black market 5.56 NATO ammo; while black market buys of Huey helicopter parts might preclude training technicians on American-made radars, and so on.

(Taken during the summer of 1979, this photo shows Soviet-made APCs disgorging from one of the defunct South Vietnamese navy’s amphibious ships. This is probably the South’s former HQVN Tien Giang, which had been the US Navy’s LSM-313 during WWII. Easy to maintain, Vietnam finally decommissioned this useful ship in 1990.)

(Ex-ARVN American-made M113s in use during Vietnam’s war against the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.)

There were other factors external to the weapons. Vietnam’s hoped-for peace dividend never really happened as Vietnam’s main aid benefactor, the USSR, was embroiled in “…it’s own Vietnam War” in Afghanistan during the Andropov and Gorbachev years, on top of a crippling arms race with the USA.

Cam Ranh Bay’s fate was typical. In January 1945, the US Navy’s operation “Gratitude” attacked the Imperial Japanese Navy base here. Carrier-based planes inflicted heavy damage, with 20 aircraft destroyed on the ground and most of the base’s fuel lost. The IJN abandoned Cam Ranh Bay thereafter. Starting in 1965, the US Navy rebuilt and extensively expanded the WWII facility, with a large deepwater port, Marine Corps barracks, and adjacent naval airfield. It was used until the American departure in 1972.

(A Soviet nuclear submarine moored to an ex-US Navy pier at Cam Ranh Bay in 1979.)

Captured intact in 1975, Vietnam leased the massive naval base to the USSR. However the rent was normally re-routed right back to the USSR via the COMECON aid system, to offset Vietnam’s running trade deficit. None of it was available to support continued use of American-made arms, certainly not WWII-vintage ones like the Garand.

The end result of all this was that ex-ARVN systems retained were either “too good to pass up” regardless of the cost, or, lesser gear which was easy to maintain but still somehow superior to combloc equipment. The M1 Garand did not fit either category. Thus, there was no large-scale adoption of the Garand after 1975.

(Even as the M1 Garand vanished, Soviet-made gear of WWII continued in use. This 1979 photo shows a village militia being trained on the PPSh-41.)

ghost rifles

What then happened to the fifth of a million M1 Garands is then something of a mystery. During the early 1980s, unexpected appearances of Garands on the world’s battlefields were almost without fail, instantly attributed to Vietnam, only to be found to have come from elsewhere later on.

(One method South Vietnam had used to store excess / second-tier rifles was empty 55 gallon drums outdoors. Some non-service weapons inherited in 1975 were probably not pristine by then.)

For certain there were exports of ex-ARVN equipment. In 1976, an organization called Cuc Quan Lý Vu Khí, Khí Tài, & Ðan Duoc (approximately “Department Handling Weapons, Gear, & Ammunition”) was created to dispense with ex-ARVN equipment. It’s existence was revealed in the most comical of ways; in 2008 an archivist in Hanoi accidentally uploaded some files onto a website serving retired Vietnamese army veterans. It was taken offline but by then widely seen.

Curiously, a file from this department dated 1982 described the weapons as leaving “cáng Sai Gòn” (Saigon port), 5½ years after the official name change to Ho Chi Minh City.

There were several exports of ex-ARVN gear between November 1976 and July 1982. Designated by an alphabetical code, they were “C” (a failed plot to overthrow Pinochet in Chile, apparently known in Vietnam as operation “Lemus”), “N” (Nicaragua), “S” (communist rebels in El Salvador), and “X” which is still uncertain but thought to be Cuba. In none of these cases were M1 Garands mentioned. The “C” shipment is the best-known; in 1986 Chilean police captured a cache of 3,000 M16s. By cross-referencing Colt serial numbers, which were foolishly not sanded off, they were positively proved as ex-ARVN rifles. Again, no M1 Garands were found in this cache.

It is known that during the 1980s Vietnam helped Iran, another American ex-ally cut off from military aid. Main items were rotors and turbines for Iran’s Huey fleet, and spare F-5 fighter parts. Iran was also a M1 Garand user and did use the rifle in combat against Iraq between 1980 – 1988, however by then the Iranians considered it a bottom-tier asset and it seems doubtful they would buy more abroad.

Part of the difficulty in tracking the post-1975 history of American-made weapons is the way the modern Vietnamese military refers to them. “Thê hê dâu tiên” (first-generation) and “Thê hê thú hai” (second-generation) are normally used in a proper military way, as in differentiating the Mosin-Nagant from the AK-47 for example. But because of the taboo mentioned earlier regarding the ARVN, “Thê hê thú hai” is also a euphemism for ex-South Vietnamese gear inherited in 1975, regardless of it’s nature – a M1 Garand from WWII and modern A-37 Dragonfly attack jet are both “second-generation” arms when referred to this way. Without knowing the context the document is using, this can be confusing.

In 1978 the legendary international arms dealer Sam Cummings approached Vietnam’s diplomat in Europe, Le Duc Tho, with a $500 million offer to buy the defunct ARVN literally in it’s entirety; everything from howitzers to handguns. Cummings told the Washington Post newspaper in 1981 that he proposed to set up shop in the USA’s abandoned Saigon embassy, which he presumed was still full of telex machines and long-distance telephone switchboards, perfect for marketing the haul. (The embassy was in fact taken over by Petro, Vietnam’s state oil concern, and later torn down.) Vietnam did not accept his offer. Several years later, they tried to hire Cummings as an arms marketing consultant to help them sell American-made gear. Cummings saw little value in starting a new competitor to his Interarms company and declined.

(Now 43 years after the end of the Vietnam War, ex-ARVN guns remain a police concern in Vietnam. Here are two M1/M2 carbines and a M16 seized in 2017.) (pnoto by Minh Anh)

In March 1997, federal agents seized two truckloads of guns at a warehouse in Otay Mesa, CA. They were labelled as “hangers”, and had originated in Ho Chi Minh City, then traveling through Singapore, Germany, and finally Long Beach, CA; with a final destination of Mexico. They were only discovered by accident due to a paperwork error. The assumed intended recipient was narco gangs inside Mexico. The main portion was M1/M2 carbines of WWII vintage, along with some M16s. According to the L.A. Times newspaper, they were traced back to old ARVN lots, and in poor condition. This would not seem like an operation endorsed by the Hanoi government, and may have been corruption inside the Vietnamese military. It’s also possible that the guns had been black marketed by the South Vietnamese themselves and had already been circulating for 20+ years. Once again, M1 Garands were absent.

For the M1 Garands, their ultimate fate is, in all likelihood, simply the least exciting story: they were scrapped after 1975. As outlined earlier Vietnam had to make hard choices as to which American-made gear it would and wouldn’t keep, and despite the M1’s legendary WWII history, by the late 1970s there was nothing remarkable about it from a military perspective compared to a M16.

(A pile to be scrapped in 1980s Vietnam; American M60 machine guns of 1960s vintage along with British-made Brens from WWII, and a Hotchkiss Mle. 1914 of the Vichy forces during WWII.)

The above photo is from a series that appears on military & firearms message boards every few years, often with differing background stories. It was actually taken at a dump in Vietnam by a British metals merchant during the 1980s. The original photo series has several piles of old guns roughly sorted by type; a stack of bolt-action rifles (including ex-Wehrmacht types), a mountain of Tommyguns, a sea of rusting WWII-era box magazines, and this pile of machine guns. This was probably the fate of most of the ARVN’s M1 Garand stockpile. During the 1980s, scrap metal was one of the few commodities Vietnam had to export in a bid to offset it’s trade deficit.

During the 1980s, while the M16 was somewhat present in the regular active-duty Vietnamese army, some M1 Garands were held in reserve along with whatever .30-06 Springfield stockpiles remained in 1975. As 5.56 NATO ammo leftover from the war was depleted, the M16s themselves were put into reserve, displacing M1 Garands which were then presumably scrapped.

(Taken around 2015, this photo shows a reserve armory in Vietnam filled with ex-ARVN equipment. Most of the guns are M16s but there are five WWII weapons; a trio of M1919A1 machine guns and a pair of M1 Garands.)

During the 1990s, Vietnam’s military “turned the corner” and became a high-tech, world-class fighting force. As part of this, manpower was streamlined and there was thus even less need for nonstandard firearms.

By 2019, the last official holder of M1 Garands in any quantity in Vietnam is the DQTV, also known as the Worker’s Militia in English. Vietnamese citizens not in the military are required to be a member for 4 years and can volunteer for more after that. Similar in some (but certainly not all) ways to the USA’s National Guard, DQTV members drill on weekends. The DQTV is armed with a variety of cast-offs; mainly SKSs and M16s but with some M1 Garands.

(DQTV members drill in 2018 with M1 Garands. A M16 is also visible.)

postscript

By 2016, the last regular-duty Vietnamese army units still using ex-ARVN guns were a few light infantry elements specifically trained on just American-made weapons, by then limited to the M16 and M1911A1.

As one of his last acts of office, President Obama eliminated the arms & ammunition embargo against Vietnam which had been in place since the fall of Saigon. In 2017 President Trump reaffirmed this policy and encouraged arms exports to Vietnam.

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.

LikeLike

Great article as always! I heard somewhere that Iran also tried to acquire ex-ARVN M48 Pattons during its war with Iraq. Do you have any information on that?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes I think they sent parts (not whole tanks) and also M113 Gavin APCs. The big thing was the turbine compressor blades for the fighter jets.

LikeLike

How could they have sent parts for an M113 “Gavin”, when there is no such vehicle?

LikeLike

its always nice to see you keep the site going. grettings from poland

LikeLiked by 2 people

Dude, you write Poland with a capital P. Always!

LikeLike

[…] More of that here. […]

LikeLike

WW2 german weapons used in the 1954 Guatemalan coup?

LikeLike

“Curiously, a file from this department dated 1982 described the weapons as leaving “cáng Sai Gòn” (Saigon port), 5½ years after the official name change to Ho Chi Minh City.”

There is nothing curious about this, the city changed name, but the port itself is called Sài Gòn and that has not changed.

Sometimes, a small detail like this really drags down a whole article. Like what else did you miss or got wrong and the readers simply can’t spot on their own to fact-check? Especially when it’s a topic that we are not familiar with. It just planted a lingering doubt in my mind. Just saying..

LikeLike

That is not accurate. HCMC’s 1st Quận is still nicknamed Sài Gòn however the actual freight harbor was renamed in 1976. The airport retained “SGN” because the IATA discourages changing the code for any reason; to the same, O’Hare Airport in the USA still has ORD from when it was Orchard Army Airfield. I think what you might be referring to, as the harbor, is the Tan Cáng Sai Gòn development project for ferry terminals which is a more recent project.

LikeLike

I would really like to see the sources for your claim here.

AFAIK before 1975, Cảng Sài Gòn was known officially as Thương cảng Sài Gòn (Port de Commerce de Sai Gon, Saigon Commercial Port). After the end of Vietnam war, it was renamed to simply Cảng Sài Gòn. Also, Tân Cảng Sài Gòn (Saigon new port) was a thing in the 60s, first started South Vietnam and later utilised and expanded by the current government. Of course, it went through a lot of changes since then, and several new ports have popped up in the area to supplement the old ports.

LikeLike

The text proclaims the M1 Garand’s size will be discussed further but then it doesn’t. The South Vietnamese were small even by Asiatic standards and the heavy M1 Garand was cumbersome for them. The M60 was also deemed cumbersome, with the ARVN using the M79 grenade launcher to mitigated their squad’s lack of firepower. The Americans took their sweet time in providing M16s to the ARVN (even though the ARVN Marines received them before the US Marines).

And speaking of marines, they are marines in the first photograph (we can see the “Sea Wave” camouflage) and in the one labeled “ARVN soldiers with M1s in the 1960s” they also look like marines.

LikeLike

Interesting article! The weight numbers for rifle and ammo are *way* off, though.

LikeLike

Col. Charles Askins was a very early adviser to the Vietnamese military. He wrote about the poor condition of the M-1s in use at the time. As a rough and ready way of sorting out those rifles which could be used in marksmanship programs he sorted out those rifles which did not allow a bullet to be inserted from the muzzle. M-1s have to be cleaned from the muzzle and cleaning rod wear means that a rifle that has seen a lot of service will have a worn muzzle and be inaccurate. A great many of the m-1s in use were probably incapable of accurate fire.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember watching a NOVA episode , depicting opium smugglers in the Golden Triangle. Every man in a foot and mule convoy of greater than 500 men , had US issue Jungle boots, A US OG uniform. A brand new ammunition belt and a US ww2 ERA weapon. Mostly M-1’s

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Pretty good read right? That’s not even half of the article, just a small excerpt. It follows the M1s all the way up to present day. Go read the whole thing. […]

LikeLike