During WWII, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s submarine force was more advanced than it is often given credit for today – mostly, due to it being overshadowed by the successes of American and German subs during the war.

Japan’s submarine force ceased to exist with the end of WWII. That it was later resurrected during the Cold War was by no means a certain thing, nor was it easy. The rebirth of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force’s (JMSDF) undersea wing is largely forgotten today, and even more so that it started with a submarine which itself had fought against the empire during WWII.

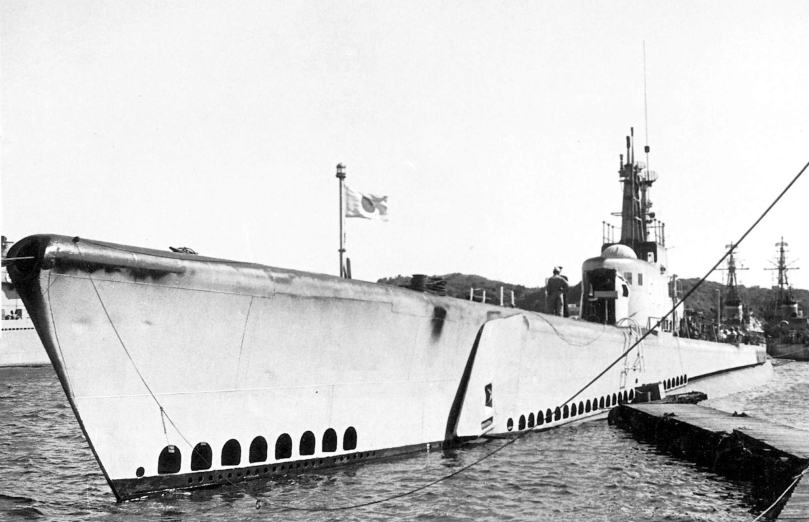

(The US Navy’s Gato class of WWII.)

(The JMSDF’s first submarine, the Gato class Kuroshio, ex-USS Mingo of WWII.)

PART I: IMPERIAL JAPANESE SUBMARINES AT WWII’S END

Excluding midget submarines; the IJN began WWII with 69 submarines of the medium and junsen (‘cruiser type’) styles; and built another 111 during WWII including the same as above, plus minelaying, transport, sentaka (‘high speed’) and the super-jumbo sentoku styles.

(IJN Ha-201 was an advanced sentaka completed in 1945. This submarine was faster and deeper-diving than American subs, albeit smaller and less-equipped. IJN Ha-201 accomplished nothing and was surrendered intact at WWII’s end. The US Navy scuttled this submarine in 1946.) (photo via combinedfleet.com website)

(IJN I-14 was a big junsen which carried an Aichi M6A1 seaplane. This submarine surrendered intact at WWII’s end (note the stars & stripes flying) and was expended as a torpedo target near Hawaii in 1946.)

(IJN I-155 was a pre-WWII design. Shown here being evaluated after the war, IJN I-155 was scuttled near Japan in May 1946.)

(This massive 140mm deck gun belonged to one of the three sentoku super-jumbos of the I-400 class, the largest submarines of WWII. These monsters carried three seaplanes, this big gun, 20 torpedoes, and enough fuel and food to circumnavigate the planet. All three were surrendered intact at WWII’s end, as seen here.)

Japanese submarines did not lack creativity or ingenuity. A total of 35 Japanese subs carried a seaplane (the three sentokus carried several). Japan had 52 submarines exceeding 3,000t displacement and 65 with 3+ months endurance. Four of the IJN’s submarines were the fastest submerged in all of WWII. Most Japanese submarines carried Type 95 torpedoes, a submarine-fired version of the excellent surface-launched Type 93 Long Lance.

Beneath these successes were problems. The first was the myriad of classes: even excluding one-offs, foreign subs, and midget / suicide types; the IJN fielded no less than 28 submarine classes plus 4 additional subvariants between 1939 – 1945. Judged by the same criteria, the US Navy fielded a larger total force but of only 11 classes, and of these the overwhelming number (226 vessels) belonged to just the inter-related Gato, Balao, and Tench classes. Besides the huge design and test effort; a lot of the different Japanese classes offered little improvement, doubled spare parts and training requirements, or were simply built in silly ways.

The photo above, taken in California near WWII’s end, shows an example of the latter. This was Yu-3, a Type 3 class cargo submarine of the Imperial Japanese Army. The IJA / IJN interservice squabbling was such that the army actually built it’s own submarines, while the navy built it’s own tanks. The IJA codenamed these crude submarines Maruyu and out of 400+ planned, only 38 were completed….not surprising, considering that they were made by Hitachi Locomotives Division, Ando Iron Foundry, and other enterprises with zero experience in submarines.

Tied in with the needlessly diverse number of classes, the shipyard priority to which submarines were given during the war was haphazard. In the USA, submarine construction was (along with aircraft carriers) a priority throughout the war up until 1944 when landing craft were more urgent. However in Japan policy vacillated: capital ships were still top priority through 1942, then destroyers & convoy escorts, then (for a brief while) submarines, and finally in 1945, almost all remaining capacity shifted to suicide vessels.

(Never-finished Koryu Type D midget submarines at Kure Naval Dockyard in October 1945, about a month and a half after WWII ended.)

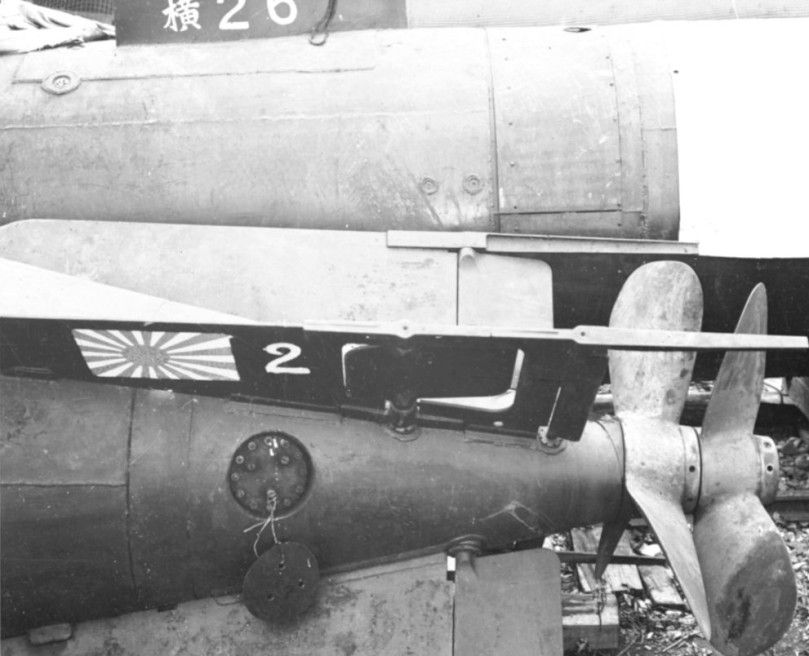

(Motor sections for uncompleted Kaiten manned suicide torpedoes at Yokosuka, during a post-WWII study by the US Navy.)

But by far, the biggest downfall of Japanese subs during WWII was bad tactics. Prior to WWII, both America and Japan foresaw submarines in the Pacific as ‘super-scouts’, probing far ahead of battleship squadrons to locate the enemy’s battleships, while picking off enemy surface scouts. The difference between the US Navy and IJN was, that after the Pearl Harbor attack, the Americans quickly switched to an anti-commerce strategy with lone submarines making hyper-aggressive, long-distance patrols targeting raw materials traffic heading to Japan’s industry. Japan meanwhile, stubbornly stuck with 1930s submarine concepts far into WWII and a lot of talented IJN captains made conservative patrols searching empty sectors of the Pacific for ‘decisive’ US Navy task forces which simply didn’t exist.

The destruction of Japan’s submarine-building industrial capacity

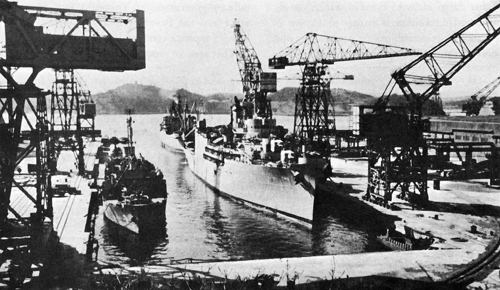

American air raids against Japanese shipyards were heavy during WWII. However, contrary to the popular notion today, they were not ‘just hit everything’-type operations. The ‘big four’ imperial dockyards (Yokosuka, Sasebo, Kure, and Maizuru) were bombed but never suffered crippling damage and in fact, did not sustain heavy damage at all until 1945 when the sea war was effectively over anyways.

Kure, where the fast sentaka type submarines were built, lost about 70% of it’s workspace (and over a thousand workers) and saw the adjoining IJN base leveled by American bombs. However the actual submarine construction drydocks survived WWII.

During the occupation, part of Kure was taken over by the US Navy. Other parts of the formerly government-owned facility (including the Yamato sized drydocks) were transferred to Ishikawajima Shipyard, or spun off into Kegoya Dock Company.

(Wrecked construction halls and workshops at Kure in September 1945, when Japan surrendered.)

(The waterfront part of Kure dockyard during the summer of 1946, about eight months after WWII ended. The flattop is the ex-IJN Katsuragi which never saw combat due to lack of aircraft, and drydocked above it is the ex-IJN Ryuhu being scrapped. As can be seen here, most of this portion of the imperial dockyard survived WWII intact.)

(The Australian destroyer HMAS Bataan at Kure in 1946. Again, there is no apparent war damage in this area of the waterfront.) (official RAN photo)

(Taken on 14 March 1947, this shows one of Kure’s drydocks being used as a dump for war debris – including a midget submarine.)

(As of 2018, the American military still maintains a small presence at the former imperial naval arsenal.)

Yokosuka was (relatively speaking) lightly damaged. This was one of the reasons it was selected by the Americans as a focal point of the occupation (it remains a US Navy base today). WWII damage was largely limited to the dockyard’s electricity grid, while several moored warships were sunk. The waterfront facilities, however, ended WWII intact.

(Turnover of Yokosuka from the Imperial Japanese Navy to US Navy on 29 August 1945. As of 2018 it remains a US Navy base.)

(A never-finished Type D midget submarine at Yokosuka after Japan’s surrender.)

(By late autumn 1945, the former imperial dockyard at Yokosuka was already fully engaged in supporting the US Navy occupation flotilla.)

Sasebo and Maizuru were even less damaged. At Sasebo, part of the base was taken over by the US Navy while Sasebo Heavy Industries was spun off from the remainder.

(The ex-IJN Ha-230 at Sasebo a month after WWII ended. The damaged carrier is the ex-IJN Junyo.)

(A battleship gun being demilitarized at the submarine facility at Sasebo in late 1945.) (photo via Robert Batey)

While government-owned shipyards escaped relatively lightly, the same could not be said of commercial Japanese shipyards which took a horrendous pounding from American B-29s. During WWII, the United States identified 25 important commercially-owned shipyards in Japan, of which 23 were considered key, and of these 23, a dozen identified as prime. These shipyards produced vessels (both warships and merchantmen) in the 1,500 – 5,000 tons displacement range. This covered most of the empire’s merchant oil tankers and cargo vessels; the same types which the US Navy was systematically annihilating with submarines and sea mines to starve the home islands of raw materials.

Compared to the big naval arsenals, these smaller commercial shipyards had every vulnerability to strategic bombing: less redundancy of shipbuilding machinery, a smaller workforce with lesser cross-training to replace lost employees, greater reliance on the utility grids of neighboring cities (themselves being firebombed), and buildings of wooden construction vulnerable to fire.

Submarine construction yards overlapped all the types of shipyards described above. Excluding midget submarines and kaiten, eight Japanese shipyards had a capability to build submarines during WWII:

Kawasaki (Kobe) (commercial)

Kawasaki (Sakai) (commercial)

Kure Naval Arsenal

Mitsubishi (Kobe) (commercial)

Mitsubishi (Nagasaki) (commercial)

Mitsubishi (Yokohama) (commercial)

Sasebo Naval Arsenal

Yokosuka Naval Arsenal

The destruction of Japan’s submarine industrial base was thorough. Both of the commercial yards at Kobe were utterly destroyed, as was Kawasaki’s Sakai plant, while the fate of Mitsubishi’s facility at Nagasaki needs no elaboration. Of the government-owned facilities, their fates are described earlier. The Mitsubishi yard at Yokohama was the only commercially-run submarine plant to escape WWII even partially intact.

(Mitsubishi’s Yokohama yard after Japan’s surrender.)

(Never-finished midget submarines at Mitsubishi’s Nagasaki shipyard in September 1945, about half a month after the end of WWII. The submarine hall was about 2,900 yards south of ground zero on 9 August and suffered light damage, however the near-total loss of it’s workforce rendered this irrelevant.)

Japan’s submarine industry was even more easily disrupted than surface ship construction, due to the specialized equipment and labor skills involved. By 1945, new workers were only given 8 weeks training, and welding transformers were by then a finite commodity as they wore out due to the home islands being cut off from copper.

As the occupation started in September 1945, Japan no longer had a realistic submarine industrial base, regardless of what political decisions lay ahead.

The fate of surrendered IJN submarines and final dissolution of the force

Excluding incomplete hulls, midgets, and kaiten manned torpedoes; 46 Japanese submarines survived WWII. Their conditions ran the gamut from brand new vessels awaiting sea trials to worn-out obsolete types.

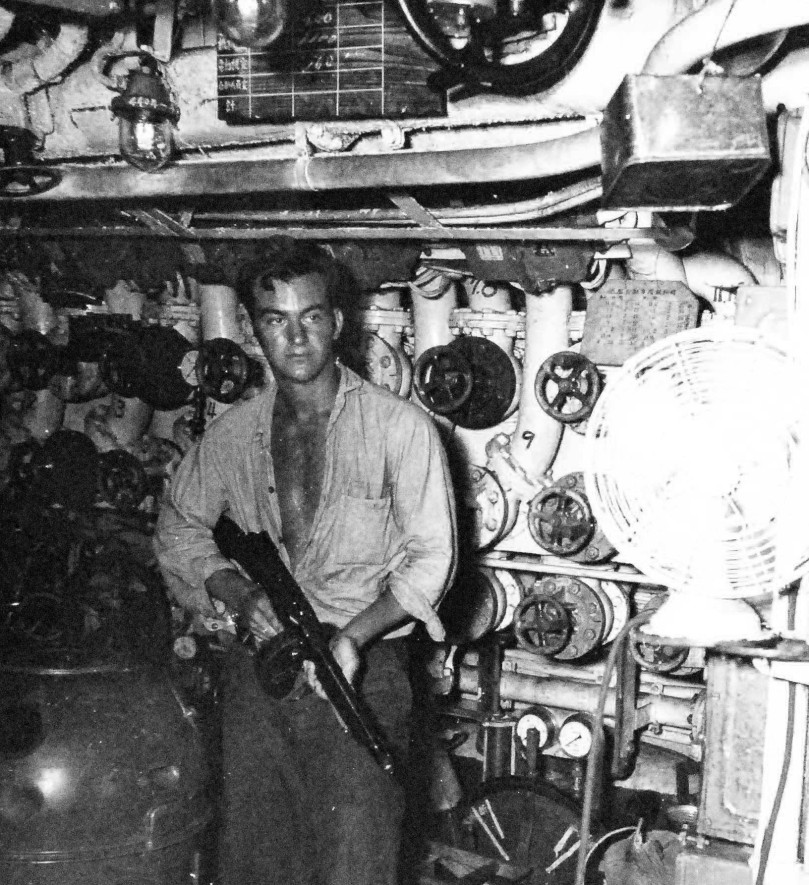

(A US Navy tommygunner aboard IJN I-14 when the submarine surrendered on 29 August 1945.)

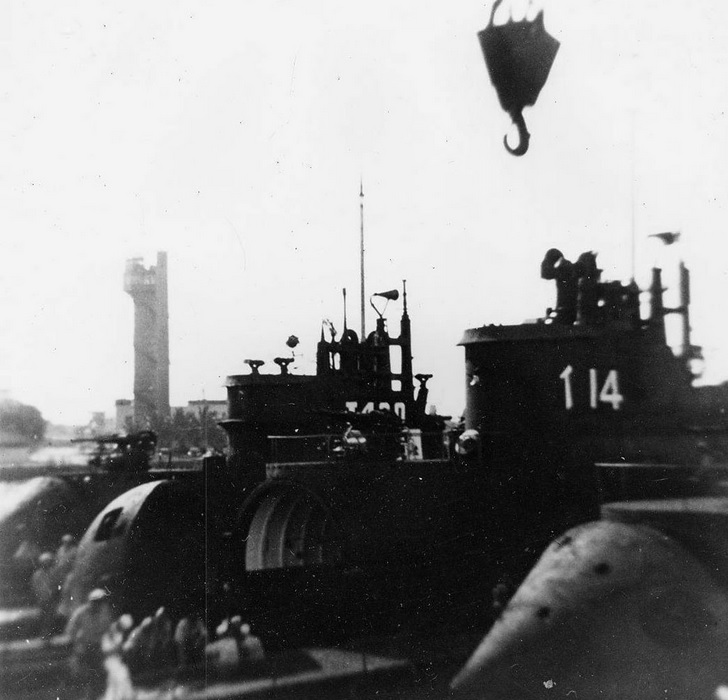

(The submarine tender USS Euryale (AS-22) with three Japanese subs nested outboard at Sasebo in November 1945.)

NavTechJap study of submarines

During the late autumn / early winter of 1945, a team known as US Navy Technical Mission To Japan (more commonly, NavTechJap) compiled an astonishing volume of studies and analysis on the defeated imperial military. These reports were a mixture of hands-on tests, personal studies, research of Japanese archives, and interviews with Japanese personnel. This all took place in the brief window before surviving Japanese ships and weaponry were scrapped, while funding was still available in Washington, and when memories were still fresh.

The focus of NavTechJap was four-fold: to glean any IJN technology that the US Navy could incorporate into future vessels; to obtain trade secrets that might benefit American defense companies; to objectively gauge the effectiveness of America’s own wartime intelligence-gathering; and preservation of history. Included was a detailed analysis of IJN submarines in general, along with supporting studies on batteries, sonar, torpedoes, hull paints, and so on.

Of the surviving submarines 25 were selected for study and of these, 9 for a full and complete analysis.

(Ex-IJN I-401 was one of the NavTechJap study ships. In this October 1945 photo, the US Navy is conducting an awards ceremony on the aft deck. The sub in the background is possibly I-401’s sister ship, ex-IJN I-400.)

Altogether the NavTechJap findings on the IJN’s submarines were in line with wartime expectations, however with a few surprises, both positive and negative. Generally, Japanese submarine technology started WWII at a surprisingly decent level but then peaked early and stagnated afterwards, less the introduction of snorkel technology from Germany.

Regarding Japanese batteries, little improvements had been made during WWII. The US Navy recovered some of the Type A midgets lost in the December 1941 operation “Z” against Pearl Harbor and found their batteries to be “…..glorified automobile batteries”, simple lead-acid units encased in a jar of solidified rubber, lined up in banks. Now in 1945, examining the late-war I-201 sentakas, NavTechJap found that these high-speed subs simply used the same type of battery – albeit, arranged in big 1,396- and 696-jar banks. These batteries output 20% less than American batteries occupying the same volume. They were also prone to fire, being lined up in such huge banks. On the fast sentakas, they only lasted about 100 recharge / drain cycles. Japanese personnel told NavTechJap that a new battery design would have been introduced in late 1945 had WWII continued.

Of special interest were hull coatings, of which there were two. Above the waterline, an “anti-radar coating”, resembling grooved adobe, was applied with trowels. Below the waterline, submarines received a “sound absorbing” coating of asbestos-impregnated hardened gum glued onto the hull. Studies were done on both, and samples shipped back to the USA. It was determined that the anti-radar coating was ineffective (the drag also caused a 1 kt speed loss submerged) and the acoustic coating was of marginal effect.

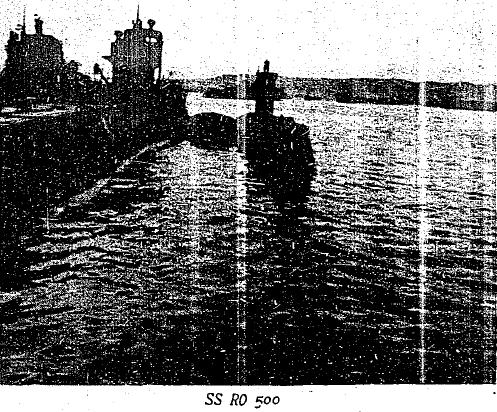

(The surrendered IJN Ro-500 as photographed by NavTechJap. Originally U-511, this u-boat delivered a new German ambassador to Japan in 1943, along with technological documents including jet aircraft data.)

(The control room of a Koryu midget submarine from the NavTechJap reports.)

One surprise was that the Japanese had perfected an automatic hovering system for submerged submarines, allowing them to remain stationary in the same location. This was not immediately incorporated into postwar American subs but the concept was revisited later in the Cold War as the first atomic-powered submarines came on line. It’s not thought that any IJN technology was of value by then.

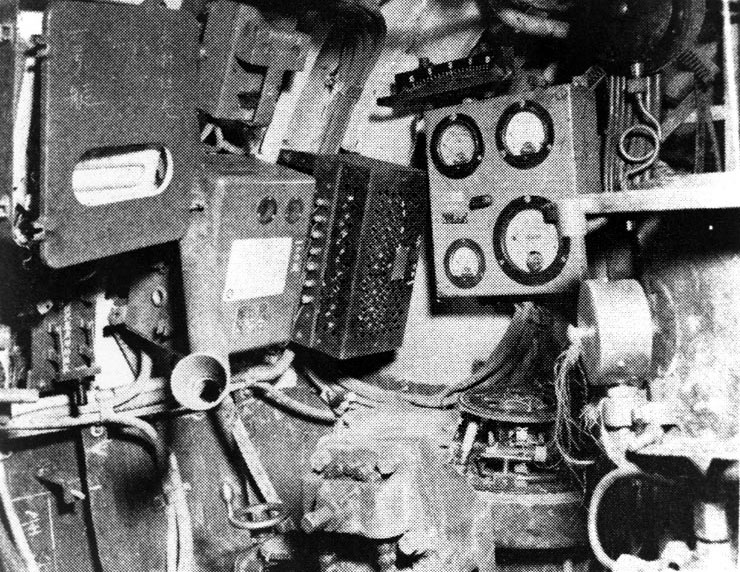

In regards to submarine electronics, the US Navy had already surpassed Japan and the findings were of no use. In particular Japanese sonar lagged far behind the USA; during all of WWII only one (the Type 4) new submarine sonar came into use.

(NavTechJap sketch of a hydrophone design from a IJN submarine sonar.)

(NavTechJap photo of IJN submarine radio gear.)

Japanese submarine building techniques were studied. Similar to Electric Boat in Connecticut, Japanese shipyards used x-rays to inspect pressure hull welds, however only a 10% sampling of welds was inspected. Overall, Japanese submarine building during WWII was a constant struggle to reduce raw materials and cut production times, not to advance technology. This is understandable considering the strain the industry was under.

end of the road

At the August 1945 Potsdam Conference the USA, Soviet Union, and Great Britain agreed on a general framework of what would be done with the IJN once Japan was defeated. The very generalized outline was disposal of “major ships”, understood to be cruisers and above, and a joint division of whatever was left.

This framework was vague, which is understandable as WWII was still ongoing (less those with knowledge of the Manhattan Project, it was generally expected to continue into the summer of 1946) and it was uncertain what would be left. Regarding Japanese submarines, nothing specific was said. This was in contrast to the main part of the so-called Potsdam Naval Protocol, which spelled out a quite detailed division of the Kriegsmarine’s remains. Here, each ally was to retain 10 surviving u-boats each, with smaller allocations to the French and Dutch.

Four IJN submarines (all of them u-boats taken over by Japan when Germany surrendered) had been marooned in the Far East when Japan surrendered. These were taken over by the Royal Navy. The British had no interest in them and scuttled them. Beyond these four, every surviving Japanese submarine was under American control.

(At least to Americans, IJN I-58 is the most famous individual Japanese submarine of WWII. Besides successfully deploying kaiten manned suicide torpedoes, IJN I-58 sank USS Indianapolis (CA-35) in the war’s waning days. Shown here four months after WWII’s end, ex-IJN I-58 was scuttled on 1 April 1946.) (official US Marine Corps photo)

General Douglas MacArthur, in his new role as Supreme Commander Allied Forces (SCAP); the ruler of occupied Japan; viewed surviving Japanese submarines as America’s alone to dispensate.

In 1946 an organization called the Far Eastern Commission began to meet. Established in Moscow in December 1945, it was supposed to be a multi-national influence on MacArthur’s occupation of Japan. The FEC had four chair members (Great Britain, the USA, nationalist China, and the USSR) and nine to eleven junior members. The four chair members each had veto power over anything and each other, and to nobody’s surprise, the FEC thus failed miserably.

One of the FEC’s duties was to finalize a dispersal of surviving ex-IJN warships. These were already declining in number: some had been demilitarized as transports or for clearing leftover minefields. For others, Gen. MacArthur himself had not waited for FEC to make a decision and simply ordered them scrapped. It was decided that surface warships above 3,800 tons (basically anything bigger than a destroyer) would be disposed of by the USA, with the balance allocated out. To avoid a repeat of the bitter arguments regarding ships of the Kriegsmarine in Europe, ex-Japanese warships were to be chosen by random drawings, which was finally done in 1947. However no agreement was ever struck regarding submarines.

As early as December 1945, with the NavTechJap studies finished, the consensus in the US Navy was that surviving Japanese submarines should simply be destroyed right away. For Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, there was no benefit to doling them out: advanced navies like Australia were already technologically ahead and didn’t want them; and to lesser Pacific navies submarines would simply be force multipliers to distort the balance of power in the area. Especially, it was desired that the USSR get none. The US Navy was decommissioning many anti-submarine ships with WWII over, and pivoting what remained towards the Atlantic. The last thing wanted was a free bump to the Soviet Pacific Fleet’s submarine arm. Nimitz’s views of course were in agreement with MacArthur (who wanted everything from Arisakas to Zeros destroyed immediately); and were shared by Admiral William Leahy, the naval aide to President Truman. Leahy relayed this to the President, further suggesting that he simply ignore the State Department which was receiving pressure from the Soviet Union on the Japanese submarines, and act unilaterally.

Another issue is that submarines were a hassle to the occupation forces. Unlike a howitzer or warplane which can be put in a warehouse and ignored, a submarine – even inactive – requires at least minimal efforts to stay afloat pierside. Before WWII, the IJN was renown for it’s seamanship standards. But during the NavTechJap studies, it was often noted that submarines were rusty, foul inside, and sometimes infested with rodents. Part of this was from the severe stress the force was under in the war’s final months, while some was due to a collapse of morale after the emperor’s surrender broadcast in August.

(The glum caretaker crew of ex-IJN I-58 in January 1946.)

On 26 March 1946, a submariner’s conference in Washington DC was informed that the decision to destroy surrendered Japanese submarines had already been made. Less the few moved to Hawaii (described later below) all sea-going types were to be scuttled, with midget types and kaiten broken up ashore. Several days later this was released to the general public, including an infuriated Soviet ambassador.

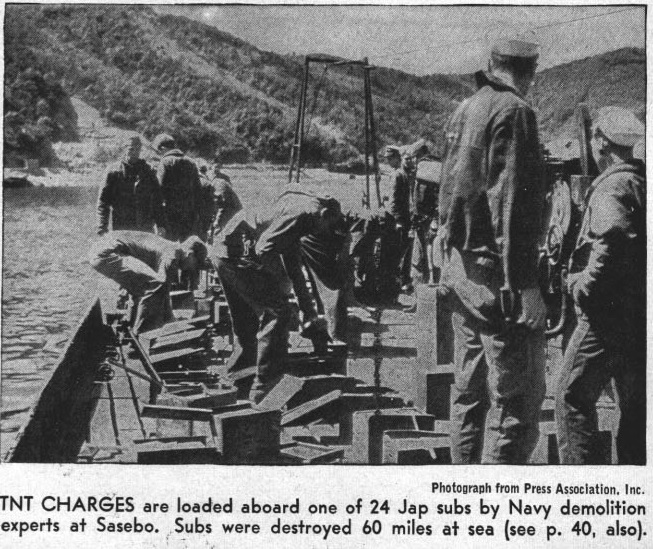

On 1 April 1946, operation “Road’s End” was conducted. Two dozen ex-IJN submarines – the whole lot in Sasebo still capable of movement – were taken to a deep spot off Goto-Retto island and blown up with demolition charges.

(Preparations for the “Road’s End” operation in late March 1946, from the US Navy’s magazine All Hands.)

(ex-IJN I-56 and ex-IJN Ha-203 tied together for scuttling in 1946.)

Other scuttling operations (including “Dead Duck” in April) took place. In May 1946, the Royal Australian Navy scuttled some in operation “Bottom”. By January 1947, the destruction of seagoing Japanese submarines was nearly complete. Ashore scrapping of the small / suicide types was ongoing, hampered only by the need to collect the craft from isolated bases. The last of these was found in 1989 when a kaiten suicide torpedo, untouched since 1945, was discovered by a private company in a hidden basement underneath a building which had once been part of the IJN base at Hikari.

(The final extant imperial seagoing submarine was ex-IJN Ha-204. It missed the scuttlings and was scrapped in 1948.)

(The final extant imperial seagoing submarine was ex-IJN Ha-204. It missed the scuttlings and was scrapped in 1948.)

fate of the jumbos

For Gen. MacArthur and Adm. Nimitz, concerns over the Soviets getting ex-Japanese submarines were generally philosophical. However regarding the very big aircraft-carrying types, there was a precise, identifiable danger already in 1945.

(The June 1946 issue of All Hands, the US Navy’s magazine, ran a feature on advanced German and Japanese submarines of WWII. This photo of IJN I-14 was taken in September 1945 but only cleared for publication after the 4,838t-displacement submarine had been scuttled off Hawaii.)

Soviet intelligence became aware of the junsens (the Type A1 / I-13 class and Sentoku-gata / I-400 class) in 1945. After American occupation troops began coming ashore, the USSR began pestering the State Department for immediate access to these specific types in addition to a demand for them in the final disposition.

(The ex-IJN I-401 moored alongside USS Proteus (AS-19). This submarine was only 129′ shorter than the massive American tender itself. Here, an American sailor is inspecting the hangar door which opened up to the catapult.)

(The ex-IJN I-401 moored alongside USS Proteus (AS-19). This submarine was only 129′ shorter than the massive American tender itself. Here, an American sailor is inspecting the hangar door which opened up to the catapult.)

Without waiting for diplomacy, General MacArthur ordered the third sub of the I-400 class, ex-IJN I-402, scuttled as part of the “Road’s End” operation. Likewise he ordered that the never-commisioned IJN I-15 of the I-13 class, 90% complete, immediately broken apart at the shipyard in 1945.

The I-400 class in particular was unlike anything the NavTechJap team had ever seen. At 400′ in length and displacing 6,670 tons, these monsters were physically bigger than a Gearing class destroyer. The streamlined outer hull concealed two twin pressure hulls inside. Atop them was a 102′ hangar for three seaplanes. The conning tower was offset, like an aircraft carrier’s, to avoid disturbing the hangar. This class was fitted with a snorkel, two radars, and long-distance radio gear. They had enough range to go around the world.

Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto originally proposed a daring mission to bring the Pacific war to the USA’s east coast, by having these submarines launch Doolittle-type raids against Washington DC. Later suggestions included bombing San Francisco and the Panama Canal. Finally in 1945, they were tasked with mounting a raid on the US Navy base at Ulithi. WWII was over before this happened and in the end, these giants accomplished nothing.

The biggest concern after WWII was not seaplanes, but cruise missiles. The pneumatic catapult on the Japanese submarines was similar to ground equipment the Germans used to launch V-1 buzz bombs at London. The Soviet Union had already gained access to both V-1s and launchers after Germany’s surrender.

(A modified V-1 being tested in the USSR after WWII.)

The danger was obvious: a combination of the German buzz bomb and the Japanese submarine with launching ability and trans-oceanic range, would immediately gift the Soviets with a method of attacking the United States. Indeed, a year later, the submarine USS Cusk (SS-348) was modified with a hangar similar to the Japanese design and test-fired a JB-2 Loon, the American facsimile of the V-1.

Worse, American intelligence estimated in January 1946 that the Soviets were between 5 – 9 years away from their own atomic warhead (they were actually only 3½ years away).

By October 1945, Soviet demands for access to these submarines became specific, calling them out by name. While Gen. MacArthur could simply ignore the Soviets, the State Department still had to maintain some cordiality with the USSR while particulars of postwar Europe were decided. Inside the then-new Pentagon there was a fear that civilian diplomats would allow the USSR access to the Japanese subs as a negotiating tactic.

The US Navy decided that the best immediate action was to get them out of Japan. Moving the vessels to the American homeland would allow more detailed inspections, and also add a psychological barrier to any foreign claim.

In November 1945, preparations were made to move ex-IJN I-400, ex-IJN I-401, and ex-IJN I-14 along with ex-IJN I-201 and ex-IJN I-203; the two surviving fast sentakas which Nimitz also didn’t want the Soviets to get. USS Greenlet (ASR-10), a submarine rescue ship, was assigned to the project as an escort. On 11 December 1945, the three super-jumbos departed Japan. Although the crew had only several weeks to learn basics of the design from the Japanese (the journey was entirely on the surface) it was still a risky endeavor.

On 6 January 1946, the three super-jumbos arrived at Pearl Harbor together. The two smaller subs arrived separately, one under tow as it had broken down.

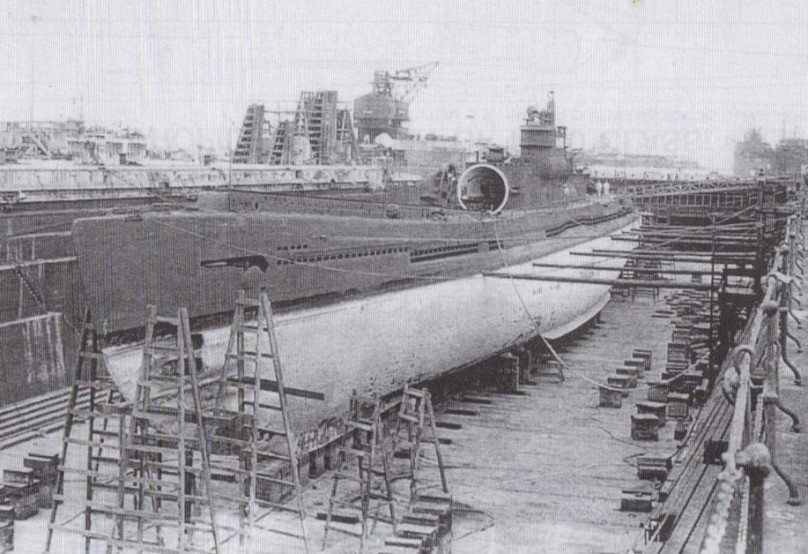

(Ex-IJN I-400 in Drydock #1 at Pearl Harbor in early 1946. Just four years previous, this same drydock was busy repairing ships of the 7 December 1941 attack.) (photo via navsource website)

Unlike the German U-3008, there was no desire to induct the “I Boats” into the US Navy. As much analysis as possible was to be done as fast as possible, and then they would be scuttled.

(The “I Boats”, as they were called by their American crews, being serviced at Pearl Harbor in 1946.)

The Soviet Union repeatedly demanded these submarines from the US State Department. In May 1946, the US Navy decided the risk of allowing them to continue existing outweighed their benefit, and they began to be scuttled in deep water south of Hawaii. The two sentakas were sunk in mid-May, then ex-IJN I-14 on 28 May, ex-IJN I-401 on 31 May, and finally ex-IJN I-400 on 4 June.

(The end of ex-IJN I-400 in June 1946.)

PART II: REBIRTH OF JAPANESE SUBMARINES

Surprisingly the Imperial Japanese Navy continued to briefly exist after the end of WWII on 2 September 1945. The GHQ in Tokyo operated for another 11 days to effect an orderly wind-up. The Imperial Japanese Navy itself continued to exist under the US Navy’s 5th Fleet until 30 November 1945, as it was a useful mechanism with existing chains-of-command for issuing SCAP orders to entire demobilizing flotillas, squadrons, and bases; as opposed to needing American units have to do the same individually for each. Every Japanese ship and base was demilitarized by 1 December 1945. On that date, what remained of the IJN was renamed 2nd Demobilization Bureau. This dwindled down and was finally disestablished on 1 January 1947.

As the occupation started, Japanese shipbuilding was limited to merchant replacements, and even then, restricted in size and speed (15 kts). This was to forestall any possible later conversion to military use. Coincidentally (or maybe, not coincidentally) it made them financially uncompetitive against American cargo lines.

Construction of warships was forbidden (at the time, it was thought forever) and submarine building was not even in the realm of imagination. This was largely a moot point anyways. Beyond damage inflicted during WWII, part of the “Pauley Plan” called for Japanese shipyards to be knocked backwards to 1930s technology with “excess equipment” sent to American shipyards. Advanced items (heavy welding electrodes, stress test gear, etc) was sent across the Pacific. Little of it benefited American companies. Some was simply sold right off as scrap metal.

Gen. MacArthur was lukewarm to the Pauley Plan in 1946 and openly ignored it by 1947. But by then, any residual capability to build submarines in Japan was gone.

Article IX

Japan’s 1947 constitution renounces the country’s right to wage war, or to maintain a war potential. But even early in the occupation, Gen. MacArthur tasked the US Coast Guard with giving some semblance of organization to the Japanese minesweeper flotilla. This evolved into the Maritime Safety Agency (MSA).

By 1950, the idea of a permanently demilitarized Japan was not as popular in Washington as it had been on VJ Day. There was clearly never going to be a resurgence of imperialism, however, taxpayers were frowning on the cost of American warships defending the islands, presumably forever.

That year some armed vessels of the MSA were split off from the buoy-tenders and rescue ships into a separate wing called the Coastal Safety Force, a supposed ‘sea police’ which was a navy in everything but name. In April 1952 the occupation ended. In 1954, the Diet (Japan’s legislature) passed the Self-Defense Act. While not repealing the constitution’s non-military stance, this law creatively defines the words “war potential” in Article IX to mean forces “…in excess of those required for self-defense”. As such, in 1954 there officially was no new ‘military’ but rather Japan Self-Defense Forces: JGSDF (land), JASDF (air), and JMSDF (sea). Each was limited to ‘defensive only’ weapons, a vague amorphous concept.

(JMSDF officers several months after the force’s legal creation.)

For the JGSDF the limit is irrelevant as post-WWII Japan has no land borders. For the JASDF, ‘defensive only’ was understood to prohibit ballistic missiles and strategic bombers, but allow most anything else.

For the JMSDF, the issue was more vexing. As easily as a Japanese destroyer or frigate could legitimately defend the Japanese homeland, it could also threaten neighboring seas as the IJN’s had done nine years previous.

With submarines this dilemma was even more pronounced. During WWII the IJN considered submarines offensive weapons, as had the wartime enemy, the US Navy, now the JMSDF’s main ally. Finally, as technology advances submarines face an inevitable ‘upwards spiral’: as onboard systems improve, they grow in size and power requirements, which needs bigger engines and batteries, requiring larger pressure hulls, which adds additional fuel and operating range, which then need more onboard systems and more size, and so on and so on.

USS Mingo becomes Kuroshio

In 1954 Japan estimated any future war would likely be against the USSR. As the Soviets then lacked major surface combatants in the Pacific, it was assumed (probably correctly) that they would employ the same tactics the US Navy used during WWII, using submarines to choke off the Japanese homeland.

To that end, the JMSDF’s first generation of warships was tilted towards anti-submarine warfare (ASW). The biggest handicap was not ASW weapons (readily sold by the USA) but rather training: the JMSDF had no way to practice ASW in peacetime, as it had no submarines of it’s own for the surface ships to train against.

During the early 1950s the US Navy provided this by assigning temporary duty to Pacific Fleet subs to act as OPFOR (opposing forces) simulators. This was not ideal to either side: For the Americans, it meant taking a sub off patrol rotation and journey out of area to Japan. As the exercises were for the benefit of the JMSDF, the American crew of the OPFOR ‘tackling dummy’ received little experience, but the American taxpayer bore the cost. Meanwhile for the Japanese, they had to quickly throw together wargames based on another country’s schedule. The language barrier lessened post-exercise meetings between the OPFOR sub and Japanese surface ships.

In July 1954, a group of JMSDF officers began efforts to obtain a submarine. As the country no longer had the ability to build one, a surplus American vessel was the only option.

The US Navy was willing to provide a WWII-era submarine; in fact it was so eager to get out of the OPFOR-sharing arrangement it probably would have given the JMSDF two if they’d asked.

More difficult was Japanese politics. The group probably realized they should act very quickly, while the Diet (Japan’s legislature) was still struggling to interpret what the new Self-Defense Law did and didn’t allow under Article IX. It was realized that extreme pacifist legislators were a lost cause, while the few nationalists would approve anything. What was key was the much larger political middle, pacifist but moderate. It was stressed that the submarine would be strictly for training only, and would not undertake operational patrols. After bitter debate, enough support was granted to go ahead with the project.

the Gato class

The future Kuroshio was USS Mingo (SS-261), a Gato class submarine built by Electric Boat in Connecticut and commissioned in 1943.

(USS Mingo during WWII.)

The Gato class measured 312′ x 27’3″ x 17′ and displaced 1,468t surfaced and 2,424t submerged. It had four diesels powering four electric motors, linked to two reduction gearboxes turning two propeller shafts. Underwater power was provided by two 126-cell Sargo lead-acid batteries. The Gato class had a top speed of 21 kts surfaced and 9 kts submerged on batteries. The US Navy designed this class with the open Pacific in mind, and it had a 75 day patrol endurance. The class had six 21″ tubes forward and four aft, and carried two dozen torpedoes plus a deck gun armament which varied. The Gato was considered a successful design that lead to the follow-on Balao and Tench classes which the USA finished WWII with.

During WWII USS Mingo made seven patrols, sinking numerous Japanese merchants, an IJN destroyer, and damaging a cruiser.

The US Navy finished WWII with a luxury none other had; a surplus of advanced submarines. The Gato design, while good, was no longer cutting-edge. USS Mingo was decommissioned into mothballs.

(USS Mingo in mothballs in California after WWII.)

first postwar Japanese submarine crew

In December 1954, the first JMSDF submarine crew arrived at the US Navy Submarine School in Groton, CT. The crew (9 officers and 72 enlisted) was a mix of ex-IJN veterans and junior seamen too young to have served in WWII. Also traveling to Connecticut was a team of interpreters, and several recorders who would transplant what they learned into a basic curriculum when the JMSDF opened it’s own submarine school.

The course at Groton is normally 8 – 10 weeks; for the Japanese this was extended to 6 months. Almost the entire faculty in 1955 were veterans of the war against Japan, however there were no hesitations or problems with training the JMSDF sailors.

As far as the actual sub they would receive, USS Mingo was selected for several reasons. This submarine had a “mild steel” pressure hull, limiting it to 300′ depth. It had never received a snorkel. However late in WWII, it received the “Mod 3” Gato upgrade with a sonar, newer radar (SJ surface search and SV air detection), and revised deck gun fit (a Mk17 5″ gun aft replacing the old 3″ forward, 40mm AA guns on the conning tower’s cigarette decks, and a 20mm on the stump of the forward deck gun).

Of all the mothballed subs on the west coast, USS Mingo was ideal as it was advanced enough to give good training value for the Japanese, but now ten years after WWII, would have been unattractive for American use due to the lack of modernizations.

On 20 May 1955, USS Mingo briefly recommissioned into the US Navy with an American crew specifically to ensure an orderly handover to Japan.

(Official Mare Island Naval Shipyard photo of the reactivated USS Mingo in 1955. The WWII-era light AA guns would have been ineffective against Cold War jets and were not wanted by the Japanese, and thus left off.)

During the summer of 1955, the JMSDF crew moved from Connecticut to San Diego, CA to begin actual hands-on training. The American crew remained with USS Mingo to assist.

(Cpt. Masahiko Moringa and LCdr. Karl Kunz aboard USS Mingo during the 1955 turnover to Japan. Both were Pacific WWII veterans.) (photo via navsource website)

On 15 August 1955, USS Mingo was formally handed over to Japan via a no-cost loan. The submarine was renamed Kuroshio, a name previously held by a destroyer sunk in WWII.

(IJN Kuroshio was launched in 1938 and sunk in 1943. The JMSDF recycled ship names of the Imperial navy without controversy.)

(The new Kuroshio in 1955, still painted in American markings but with Japanese flags. Most of the US Navy’s ‘old salts’ in the mid-1950s were WWII veterans and it must have been remarkable to see a resurrected Gato flying the Rising Sun.)

Kuroshio remained in San Diego for several more weeks to ensure no aspect of the training had been missed. On 24 October 1955, Kuroshio arrived safely in Yokosuka.

return of the Rising Sun flag

Japan’s national flag is the Nisshoki, simply the sun on a plain white field. In the west this is often called the ‘red disc flag’. When western readers think of the ‘rising sun flag’, what they often mean is the Jyurokugo Kyokujitsu-ki, the military ensign with 16 rays. This design dates back to the mid-1800s and was adopted by the Japanese navy in it’s current shape & style in 1889.

Contrary to popular perception, the national (‘red disc’) flag never completely left use during the occupation. Unlike Germany which was divided four ways and utterly disestablished, Gen. MacArthur viewed Japan as an ongoing entity, temporarily under his control. Some aspects of government remained intact, but under American supervision.

(The ‘freighter’ Wakataka, formerly IJN Wakataka, about a year and a half after WWII. This destroyer was demilitarized and used to repatriate Japanese forces back to the occupied home islands. The national flag is painted on the hull.)

In 1945 – 1946, the civil flag’s use required explicit permission from SCAP in Tokyo. Later broad blanket permissions were granted, and towards the end of the occupation SCAP delegated Japan the right to grant permissions, to lighten the bureaucratic workload.

Regarding the military (‘rising sun’) ensign; no organization remained with authority to fly it after the 1945 surrender. There was a push by the American military to have it declared de jure illegal, like the swastika in Europe, but this was never done. In Germany, things like the swastika existed for only a blip in time and were specifically linked to the nazi party. In Japan, the rising sun had existed for half a century and had no political links. During the occupation, the ensign was unauthorized but there was no real effort (outside of souvenir hunters) to collect or destroy existing flags.

One proposal to permanently ban the ensign made it as far as needing only Gen. MacArthur’s signature. He never replied yes or no. With MacArthur, this was often an unspoken signal that he viewed a topic as too trivial to be bothered with.

When the Coastal Safety Force split from the MSA, the question of the ensign was raised, as it had never actually been banned by the Americans. As the Coastal Safety Force became the JMSDF in 1954, the ‘rising sun’ returned to service, with no reaction either politically in Japan or from the US Navy. In retrospect today, the latter is surprising, considering the animus which characterized the Pacific fighting that ended only nine years previous.

(Colors ceremony aboard Kuroshio.)

Kuroshio in Japan

(Kuroshio in 1957.)

Although the JMSDF had succeeded in getting it’s training submarine, there was still political apprehension on the topic. For some time the Kuroshio was not even based at a JMSDF facility but rather homeported at the US Navy base at Yokosuka, where American gate guards served as a buffer against the Japanese press. Elaborate, sometimes absurd, measures were taken to keep the vessel’s media profile at a minimum. The JMSDF never referred to Kuroshio as a sensuikan (submarine), but rather a variety of euphemisms: “Underwater Target Device”, “Special Training Unit”, and so on. The crew was specifically instructed to never use the word sensuikan in public. This even extended to the spare parts book; for example submarine gaskets became “rubber of the special purpose”.

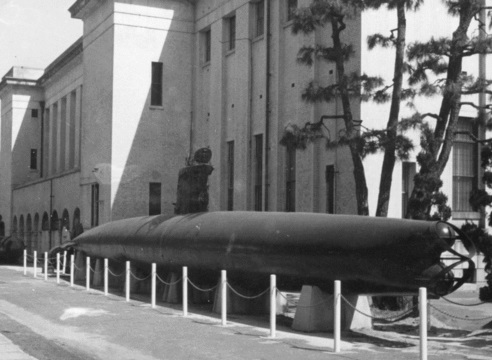

(When the Etajima advanced training facility reopened it was gifted a surrendered Type A midget sub by the US Navy. During WWII the Imperial navy used the term “Special Armor Target” for the Type A as a secrecy measure; now this was (quite amazingly) revived so the school could avoid saying it owned a midget submarine.)

Obviously all this did not fool anybody, but the objective was to remain as humble as possible, and avoid the impression that the JMSDF was rubbing it in the faces of pacifists who were a majority in the Diet.

As far as it’s actual assigned task, Kuroshio did the job well. In terms of size and radiated noise levels, the Gato class was similar to the early Cold War diesel subs of the USSR, such as the “Zulu” and “Whiskey” classes.

(The Japanese left the Mk17 deck gun aboard Kuroshio. It no longer had any military function but it created flow noise underwater. Normally this would be a negative, but in Kuroshio’s training role, it enabled rookie sonarmen on surface ships to more easily detect the submarine.) (official JMSDF photo)

One change the Japanese made was to the conning tower. The forward cigarette deck, now pointless without it’s WWII anti-aircraft gun, was enclosed in for a bad-weather surfaced conning station.

(Kuroshio’s new enclosed forward station, with a quarter-spherical plexiglass ‘flying bridge’ above it. This was a typical item aboard American-exported diesel submarines in the 1950s – 1970s.)

(A side view of Kuroshio. During WWII submarines were painted haze grey. Early in the Cold War it was determined that black offered more concealment at periscope depth.) (official JMSDF photo)

In 1959, the JMSDF lent Kuroshio‘s services to a movie studio for the film I-57 No Surrender. Kuroshio stood in as that IJN submarine of WWII for outside scenes. Starting in May 1965, Kuroshio began training the JMSDF’s first specialized submarine rescue teams, as well as continuing on with the normal OPFOR training against Japanese surface warships.

return of submarine sonar in Japan

In regards to building up a future JMSDF submarine force with actual combat abilities, the WWII-vintage JP sonar aboard USS Mingo, which was left aboard during the handover as Kuroshio, was invaluable.

The US Navy’s JP set was one of the more advanced sonars of WWII. The externally visible component was a blade-shaped T on the Gato class’s foredeck.

(This 1959 photo shows the JP sonar aboard Kuroshio trained to starboard. The frigate is Nara, which had been USS Machias (PF-53) during WWII. Made in Milwaukee as part of the wartime Great Lakes shipbuilding effort, Nara was just one of many first-generation JMSDF ships – like Kuroshio – which had fought against Japan during WWII.)

The JP sonar had two hydrophones, one on each end of the crosspiece, which rotated. A major advancement was the introduction of a visual display to go with the operator’s headphones. Called the ‘magic eye’, it was a circular screen with a lit wedge shape. It operated somewhat similar to radio tuners on old hi-fi’s. The sonarman rotated the JP towards a sound. As the sound’s source began to fall inbetween the ends of the “T”, the wedge grew narrower, until (when it was dead-center) the wedge disappeared into a straight vertical line.

By the 1950s the JP was no longer cutting edge but it was still military relevant, and frankly not much worse than early Cold War Soviet sonars. Aboard Kuroshio, it enabled the crew to undertake mock attacks on surface ships during ASW exercises. With the OPFOR role now filled, the JMSDF was already looking to use Kuroshio as the foundation of future combat submarines.

restarting Japan’s submarine industrial base

Even as Kuroshio entered service, it was realized that the WWII hull was an aged asset and would eventually need replacement. This would be a problem as Japan’s submarine industry was destroyed, and the United States might be unwilling to keep providing free submarines.

With the taboo on subs now broken by Kuroshio however, there was a desire to both restart domestic sub production and also to have subs with actual warfighting ability.

In 1954, Kawasaki began an internal effort called Special Research Room (again, euphemisms were used instead of “submarine”) with submarine shipwrights of WWII and some ex-IJN officers including former Cdr. Mochitsura Hashimoto, who had captained IJN I-58 during the successful attack on USS Indianapolis.

(Mochitsura Hashimoto during and after WWII)

Now a civilian, Hashimoto advocated both for the alliance with the United States and for a domestic ability to build warfighting submarines. Kawasaki’s Special Research Room joined a similar effort inside the company’s otherwise rival, Mitsubishi, to form a joint team called Undersea Weapons Study Group which gained recognition by the government.

Obstacles identified were pacifist opposition in the Diet, and a rapidly collapsing timeframe: metallurgists and engineers in the prime of their careers during WWII were now getting ready to retire. If they left before the industry restarted, Japan would be no further along than say, Mexico or Belgium, towards building a sub.

The main advantages were the experience being gained by operating Kuroshio, and the unique position Japan found itself in: it’s own domestic talent, records, and databases; opinions and assessments of the former enemy, the US Navy; plus new assistance from the same, now an ally.

The Undersea Weapons Study Group gained additional personnel including former LCdr. Yoshimatsu Tamori, a WWII submarine captain (also remarkable for the fact that he had been an advocate of the kaiten project during WWII, but none the less later became a vice-admiral in the JMSDF) and former Adm. Kondo Ichiro. Ichiro had been Japan’s defense attache in Washington DC until the afternoon of 7 December 1941. In 1942, he was exchanged for his US Navy counterpart at the Tokyo embassy. During his debrief, he urgently warned the IJN about submarine technology. His pleas fell on deaf ears as the empire’s admirals were still obsessed with a ‘decisive surface duel’ at the time. Now, his advice was welcomed.

The group’s hard work was successful, as in the Showa Year 31 (1956) budget the Diet granted ‘defensive only’ classification to both combat submarines and the ability to construct them domestically.

Kawasaki’s rebuilt submarine yard at Kobe launched Oyashio in 1959. A one-off design, it melded aspects of the WWII fast sentakas, the Gato class, and some postwar innovations.

(Oyashio was Japan’s first torpedo-armed, combat-ready sub after WWII, and served from 1960 – 1976, later relieving Kuroshio as the OPFOR unit.)

(Kawasaki’s submarine plant in Kobe in 2016.)

latter years of Kuroshio

After Oyashio was authorized, some of the self-imposed stigma of Kuroshio was relaxed. In August 1965, Kuroshio shifted homeports to the JMSDF base at Kure, and began to (still, sparingly) be opened to the Japanese media. Later in the 1960s, public tours were even offered from time to time.

(Kuroshio at Kure in 1964.)

By February 1965, the JMSDF had enough new submarines that formations could be created, and Kuroshio was assigned to the 1st Submarine Group at Kure. While still a valuable asset for exercises, the old submarine’s overall training worth was starting to lessen. Kuroshio never received a snorkel and now two decades past WWII, the sonar and radars had fallen quite behind the current technology level.

(Kuroshio moored inboard of Oshio, a mid-Cold War JMSDF submarine, during the late 1960s.)

On 31 March 1966, Kuroshio was renumbered from SS-501 to YAC-18. The YAC-__ category is defined as “Kept Ship” by the JMSDF and roughly means a vessel no longer suitable for it’s intended sea role but still useful inport for other tasks. Kuroshio‘s final years were spent pierside to serve as a squadron receiving barge and training hull for things not requiring actually being submerged.

On 15 August 1970, Kuroshio was decommissioned. As the 1955 handover had technically been a loan, the submarine reverted to American custody. The US Navy obviously had no use for the relic and calculated that the tow cost back to North America would even exceed it’s scrap metal value. On 13 February 1972, the old ex-Mingo was towed away to a Japanese scrapyard in Sasebo.

postscript

Shortly after Kuroshio entered service, the JMSDF sent a budget request to the Diet for a light aircraft carrier to operate small ASW planes. By then, opinions on Article IX and the Self-Defense Law had already solidified, and the ‘defensive-only’ designation was rejected and the idea cancelled. Had the submarine lobby not acted with such speed and determination in 1954, it’s entirely possible that submarines would have fallen to the same fate.

Japan’s postwar submarines advanced in capability and size with each successive generation. By 2018, the JMSDF’s submarines are as good as any other and a vital part of joint strategy with the US Navy. This impressive march of technology all started with Kuroshio. When Electric Boat was building USS Mingo to fight the Imperial Japanese Navy during WWII, this outcome could have never been imagined.

(The current Kuroshio was commissioned in 2004.)

Great article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.

LikeLike

Thanks for posting. Nice to see another installment of wwiiafterwwii.

LikeLike

It’s great to see another post after the long hiatus. The politics bare almost as interesting as the boat. Interestingly the Kuroshio served alongside a former opponent.The JMSDF Wakaba was originally the Matsu class destroyer IJNS Nashi which was sunk late in the war and then raised and rebuilt as the only IJN ship to serve post war Japan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great to see a new blog post! My blog was also inactive from January 2018 to August 2018, so I understand the circumstances that make it difficult to have regular postings.

LikeLike

Really enjoyed this one a lot!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would also add that I’ve often thought how an I-400 class submarine as a US museum would be a great complement to the German U-505 we have. Those were such unique vessels and we had to scuttle them all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on battleoftheatlantic19391945 and commented:

“Sunday, March 13, 2022-WELL, as I more than precisely ALWAYS POST a GREAT DEAL CONCERNING The Battle of the Atlantic/1939-1945; THIS TIME IT IS CONCERNING-The Battle for the Pacific; AND a SIMILAR NAVAL WARFARE, AS ANTI-SUBMARINE, THOUGH…IN ALL RESPECTS READY…AS IN READY, AYE, READY…AS W.W.II NAVAL WARFARE WAS QUITE DIFFERENT, EVEN AS IT WAS SIMILAR…DURING The Battle for the Pacific/1941-1945!!!” “

LikeLike