Since starting wwiiafterwwii, I have wanted to do something on this topic but was unsure how to approach it. I am interested in how WWII weapons performed in battle against Cold War replacements. But also, it is fascinating to consider how they ended up where they did after WWII……how did a Garand built to fight Imperial Japan end up in the Somali desert in the 1970s, or how did a Waffen-SS sturmgewehr end up in 21st century Damascus?

(An ex-Wehrmacht NbW 42 Nebelwerfer with Interarms markings in the 1960s.)

PART I: NATION-TO-NATION BASIS

After WWII, weapons of the war traded in two ways: the colorful world of private arms dealers, and governmental nation-to-nation transfers. The more boring of the two methods made up the vast bulk: 90% in the free world, and 100% in the East Bloc, where of course there was no private enterprise.

In 1946, the first full year of peace after WWII, there were only three countries on Earth in any position to make weapons exports: the Soviet Union, the USA, and Great Britain. Each of these countries had it’s own methods.

The USA:

After Japan surrendered, several arms of the USA’s federal government handled weapons sales, a notable one being the State Department’s Foreign Liquidation Commission. Thereafter, obsolete arms transferred during the Cold War were handled in one of four ways:

Title 22 transfers, often called FMS (Foreign Military Sales) was administered by the Defense Department and was simply a direct sale for cash – or more commonly, offset by a deduction from the recipient’s foreign aid, called FMS credits. The advantage to the USA was three-fold: it flushed old WWII out of inventory, helped an ally, and (per federal law) any FMS credits used had to be spent on American-made gear, denying a sale to other countries.

(Countries eligible as FMS buyers changed from time to time. This was the 1973 list, near the end of America’s sales of WWII-generation arms.)

Leases were of five-year duration and renewable. No non-NATO country could lease more than $50 million worth of arms at a time. Leases were common on expensive WWII items like warships. Loaning of equipment (basically a $0 lease) was the same arrangement.

Finally WWII weapons could be granted, in other words, given away for free. Officially this was called the EDA (Excess Defense Articles) program. France was a major recipient, receiving $289.9 million worth of free weapons between 1950 – 1963 in addition to gear granted during WWII and the first four postwar years.

(This M3 half-track was granted to France in 1951. The body joints are still caulked shut from it’s post-WWII layup.)

In the years after WWII, grant transfer was not uncommon, due to the massive output of America’s war industry between 1941 – 1945, and the huge technology swing in the 1950s.

(The final Ford GPW jeep. The handy MB and GPW jeeps were massively over-produced during WWII, and in mid-1945 production was halted as America would clearly finish WWII with a huge surplus, irregardless of when Japan surrendered. Many jeeps were later transferred abroad for free.)

For leases or sales, payment had to be US dollars or FMS credits. Almost always the recipient was responsible to pay the reactivation costs, if any. The USA retains a perpetual right to inspect weapons transferred by sale, lease, loan, or grant. As of 2018 the code name for this project is “Golden Sentry”.

It was common for these methods to be combined. WWII weapons originally leased or loaned were often sold for pennies on the dollar (or granted for free) at the contract’s expiration; as they were worth less to the Pentagon then the cost to retrieve them.

(USS Lamprey (SS-372) of WWII transferred to Argentina as ARA Santiago Del Estero under a 5-year loan in 1960. The loan was renewed in 1965 and the submarine was sold outright for a tiny sum at the end of that renewal.) (photo via navsource website)

TPTA

Third-Party Transfer Authority (TPTA) was a State Department program to re-transfer WWII weapons already sent abroad by one of the other methods. TPTAs of WWII-era weapons were common in the Cold War; especially in the orient. When Japan rearmed in 1954, it’s first generation of weapons was almost entirely WWII American. Due to Japan’s rapid economic recovery, these were quickly phased out and some were TPTA’ed to Taiwan, the Philippines, or South Vietnam.

(This South Vietnamese warship had been the US Navy’s nameless LSSL-10 during WWII. In 1950, it was transferred to France as Javeline under a 5-year lease. In 1956 it was TPTA’ed to Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Forces as Hinageshi. Already obsolete, less than a year later it was TPTA’ed again to South Vietnam as HQVN Le Van Binh. This ship was sunk in October 1966.)

the Garand and carbine programs

A total of 42 countries received the M1 Garand after WWII. The largest recipient was South Korea which received 354,363 between 1963 – 1969, on top of Garands it already received during the Korean War. The last recipient was South Vietnam which received it’s final batch of 44 Garands (out of 280,822 overall) in 1973, about a year and a half before North Vietnam overran the country.

(South Vietnamese soldiers with M1 Garands in 1961.) (photo via Life magazine)

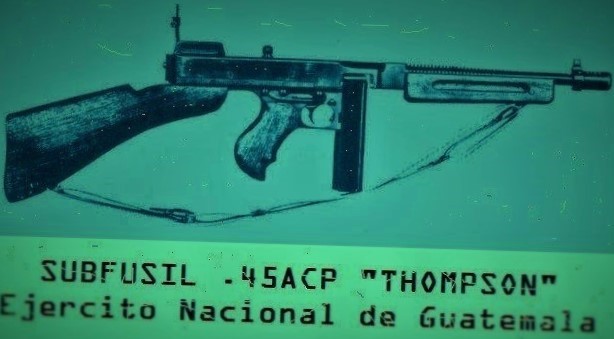

A total of 38 countries received M1 carbines after WWII (plus those who had already received them during the war). The last transfers of WWII-production M1 carbines came in 1974 (5,000 to Guatemala and 2,000 to Uraguay) and in 1976 (98 to Thailand). The Thai carbines came from US Air Force warehouses and likely represented the last of the American military’s inventory, 31 years after WWII.

(Netherlands National Police officer with M1 carbine after WWII.)

duplicity

Regarding arms sales, it was rare for a country to try screwing with the United States on a nation-to-nation basis, but it did happen. One deterrent was that abroad, this upset Congress; but actually inside the USA itself, it also fell under criminal jurisdiction of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI.

During the first years of Israel’s independence, double-handed deals and unauthorized exports were common. Contrary to the belief today, the USA did initially try to stop to this.

(A 14 July 1950 internal DIO memo on how Israel was buying parts of P-51 Mustangs from American junkyards for reassembly into complete fighters. Al Schwimmer, mentioned, was later fined $10,000.)

Another example was 1960s Portugal. As it’s African wars heated up, the Portuguese navy had a need for WWII-surplus Mk6 landing craft. These simple vessels brought men ashore at Normandy and Iwo Jima, but now, Portugal wanted them as riverine combat boats in Africa. The US Navy was not stupid, and advised the State Department that under no circumstances should WWII landing craft be released to Portugal.

(The illicit ex-WWII landing craft operating in Portuguese Guiné.)

Portugal established a front company called Progresso in the USA. It identified civilian owners of demilitarized Mk6s. (Disarmed craft were auctioned off for a pittance after WWII, making ideal workboats for fisheries, yacht marinas, etc.) Progresso bought demilitarized Mk6s and booked contracts with Fairbanks-Morse to overhaul them. The owners were glad to get rid of the worn-out vessels, and Fairbanks-Morse assumed Progresso was going to resell them inside the USA. Instead, two batches (15 and 10) were smuggled to Portugal.

The UK:

Britain’s sales and giveaways of WWII-era weapons came in spurts, as batches of colonies gained independence. The first big spurt was in 1947 during the division of Raj India. The last came in 1965 – 1966 when half a dozen African colonies gained independence.

(Ex-Royal Navy Seafire fighter transferred to the Burmese air force.)

Initially the British effort was poorly coordinated. The Ministry Of Supply (which no longer exists) handled anything made by a Royal Ordnance Works, mostly machine guns, tanks, and artillery. The Admiralty dealt in warships, the Air Ministry in RAF assets, and the army in other items. This put off some potential buyers, and in 1958 a position called Assistant Controller Of Munitions was created to handle WWII weapons of all types. None the less, by then the damage had been done. During the Cold War, nations sometimes switched from surplus British WWII arms to surplus of the USSR or USA, but almost never the other way around.

(The Header House facility was used to store British arms after WWII. By 1959, a lot of them were already transferred abroad.)

The USSR:

The Soviet war machine during WWII was second only to America’s, and the USSR ended 1945 with a massive supply of it’s own weapons, in addition to the huge quantities captured from Germany.

(Soviet captured 98k rifles after WWII.)

In the late 1940s, through the 1960s, transfers of WWII-era Soviet arms were “fraternal” (a euphemism for free) or “international”. For the new satellite countries in eastern Europe, WWII arms were almost always fraternal, decided by a steering committee that judged what they needed and could afford to keep operational. Mongolia, and later Cuba and North Vietnam, fell into this category, as did the numerous insurgent groups Moscow supported.

Sometimes these lines blurred. For example Egypt received Soviet WWII both by sale, and periodically as emergency fraternal aid, normally after a drubbing by the Israelis.

(WWII Yak-9 fighter supplied to Albania. Albania’s military was poorly run. When Albania withdrew from the Warsaw Pact, the other members were not sad to see it leave.)

For other transfers of WWII weapons, the USSR expected at least nominal payment. Typically WWII-era weapons were heavily subsidized to begin with, then sold on flattering credit terms. The norm was a flat 2% interest spread out over 12 years; which compared good to the American policy, which was the interbank interest rate in 5 years.

Soviet defense attaches did a decent job but were let down by their masters in Moscow, who let debts get out of hand. In the USA, if a recipient of WWII weapons defaulted on payments, Congress shut off the faucet for more guns. The Kremlin lacked this curb and found itself unable to say no. By the 1980s, nations such as Syria and Iraq were so deep in arrears that it was realistically unpayable.

the proxy system

The USSR made heavy use of the proxy system, both to de jure armies in the middle east and to insurgent groups worldwide. Here, when a foreign user wanted rifles, a Warsaw Pact flunky (East Germany for example) sent WWII-era Mosin-Nagants for free, and was then in turn compensated with an appropriate quantity of Cold War-era AK-47s from the USSR. By this, Moscow tried to shield itself from diplomatic fallout while at the same time, flushing obsolete gear out of the Warsaw Pact.

(After East Germany remilitarized, the Soviets supplied it with captured Wehrmacht arms, like the StG-44 and 98ks these motorcycle troops are posing with. East Germany later proxy-transferred guns of these types into Africa, Vietnam, and the middle east. In return the Volksarmee got SKSs and AK-47s.)

All of the Warsaw Pact members were required to do this. Czechoslovakia took things a step further on it’s own however. A government-owned company called Omnipol marketed obsolete arms worldwide independent of the proxy set-up. The reason was that Omnipol demanded payment in hard western currency like US dollars. This influx of “capitalist” money buoyed up the national economy.

the fate of captured Axis arms

All of the allies captured German, Japanese, and Italian arms during WWII and at the war’s end. These are conspicuously absent from postwar inventories, and were not offered by Britain or America after.

Part of this was intentional. When Germany surrendered, the UK was heavily in debt but conversely, was sitting on a mountain of weapons. The solution was obvious and in 1945 the British proposed to President Truman a system whereby liberated countries would be prohibited from using German weapons in the postwar world.

Instead, France would then become a captive market for surplus American guns, and the Low Countries the same for British weaponry. Britain predicted that the USA would go along with this, as it was already American military policy not to use captured gear.

Of course, these same countries were in no position to stick their noses up at German weapons in 1945. Many freely used them, and the British idea went nowhere.

(The 1948 edition of the French army’s manual for the MG-42, which it used into the 1950s.)

(Surrendered Luftwaffe Ju-188 bombers were adapted as search planes by the post-WWII French navy.)

On the other side of the new Iron Curtain, the Soviets had unimaginable quantities of captured Wehrmacht equipment, which it had already been using throughout WWII. The USSR saw no reason why itself shouldn’t continue to do so, and even less why it should refrain from exporting it.

(A WWII PaK-40 anti-tank gun being towed by a Cold War-era BTR-152 of the Soviet 270th Motor Rifle division during a September 1954 exercise. Even at this late of a date, ex-Wehrmacht gear was still in the USSR’s army.)

(The USSR exported captured MP-40s to Mongolia in the late 1940s.)

(MG-34s were transferred to North Vietnam.)

Japanese weapons were shunned after WWII. Some parties in crisis (both sides of the Chinese civil war, the two Koreas in 1950, and the Viet Cong) made limited use, and Thailand and Indonesia retained some into the 1950s, but generally speaking there was no appetite for Arisakas or Nambus on the world scene.

the benefits and pitfalls of demilitarization

Disarming / Demilitarization (or, “demilling”) of WWII gear naturally seemed a logical way for the victorious Allies to wring value out of wartime weapons. An example was the Shervick.

In 1947, Vickers in the UK began a huge effort to convert M4 Sherman tanks into farm tractors for Britain’s “Groundnut Scheme” in it’s African colonies. A tepid success mechanically, the Shervick died mainly because the Groundnut Scheme failed so badly, and also, because the British discovered that Shervicks were being bought on the black market not for farming but rather to extract spare parts for active M4 Shermans.

WWII warplanes were also demilled and sold as ad hoc freight movers or small passenger planes. For the most part these ended unprofitably but some flew on for a surprisingly long time.

(This demilled B-17 Flying Fortress bomber hauled freight in Bolivia.)

During the period between WWII and the Korean War the United States discovered that oddly enough, the postwar usefulness of a WWII warplane was often greater split up than the sum of it’s whole. The engine, radio, compass, and guns were more desirable than the aircraft itself.

(Wright Cyclone engines removed off B-17s at Kingman AFB in 1947. The Flying Fortress’s R-1827-90 version of this engine was cross-compatible with Cyclone versions on exported Cold War designs such as the HU-16 Albatross, S-2 Tracker, and H-34 Choctaw. It was somewhat compatible with Wright engines of WWII designs sold abroad, such as France’s SBD Dauntless dive bombers. Meanwhile the B-17 itself was obsolete.)

restrictions on use

The USA sometimes put restrictions on what recipients could do with sold, leased, or free WWII weaponry. These were very hard to enforce. Typically the only thing that could be done is to refuse future sales if violations were repeated and egregious.

(American WWII-era tanks transferred to Portugal were “restricted to operations in the NATO area” (Europe) however in 1967 Portugal sent three M5 Stuarts to fight in it’s colonial war in Angola anyways.)

(Turkey made heavy use of WWII-vintage C-47 Skytrains during the 1974 invasion of Cyprus (note the operation “Attila” emblem under the cockpit). This greatly angered the USA but there was nothing that could be done. This plane was overhauled in Turkey in 1975 and continued in use.)

leakage and blowback

One advantage of exporting surplus WWII arms as opposed to new equipment, was that it limited the damage of technology exposure. During the 1950s, having the “other side” get a F-86 Sabre or T-54/55 would have been a concern; however if a T-34 or Spitfire were to fall upon the wrong eyes; nobody particularly cared.

(Egypt’s ENS el-Fateh had been HMS Zenith during WWII. Above, Soviet sailors welcome the obsolete destroyer during a friendship visit to Sevastopol.) (photo by N. Grigoriev)

(These Israeli troops captured this Renault R35 from Syria. It’s doubtful France cared, as there was little technology to exploit from this WWII tank.)

(Egypt converted this WWII Soviet ISU-152 assault gun into a commander’s vehicle. It was later captured by Israel.)

In lingo of the arms trade, “blowback” is unintended consequences of a sale. The recipient nation could switch allegiances after the sale, which happened with some regularity. The worst of course is a country’s own exports later directly used against itself.

(This amphibious ship of the communist Chinese navy had been the US Navy’s LST-1008 during WWII. In 1946, the US Navy gave it to the State Department’s Liquidation Commission, for transfer to China. During the Chinese civil war, it ended up in Mao’s hands. China used it into the 1990s.) (photo via hazegray website)

(Fidel’s M4 Shermans on the march in 1959.)

(Mujahideen with a WWII PPSh-41 in the 1980s, ready to use it against it’s Soviet makers. The USSR had sold these guns to Afghanistan in happier times.)

a brief study: WWII arms in the early-postwar middle east

Today in 2018, the wealthy middle east is the core of the world’s arms trades. It wasn’t always that way. In 1946; the first full year of post-WWII peace; Dubai was a dusty little camel town, Kuwait City’s main industry was oystering, Tel Aviv was a kibbutz, while Beirut looked poised to displace Monaco as Earth’s premiere luxury haven. Needless to say, things changed quickly.

France intended to retain it’s Sahara holdings, while it’s two offspring in the Levant, Syria and Lebanon, were set up with quiet governments and armed mainly with castoffs of the wartime Vichy regimes there.

Britain had grand plans for the rest of the region. Libya, Egypt, Transjordan, and Iraq were all client monarchies, and all ripe markets for WWII-surplus British arms. Iraq was made a focus market, meanwhile, Egypt needed no coaxing. Repeatedly in the first half-decade after WWII, the Egyptian king made massive buys of British WWII arms of a very rash nature. Cairo’s shopping list ran the gamut, from bayonets to naval warships to Spitfires to machine guns to helmets to Archer tank destroyers to mess kits.

(Egypt purchased small batches of WWII Sterling, Halifax, and Lancaster (pictured above) four-engined strategic bombers from the RAF in the late 1940s. These expensive planes accomplished nothing and were already gone several years later.)

The Egyptian king’s habit of treating taxpayers as an army piggybank did not endear him to his subjects – a lesson that the shah of Iran should have remembered three decades later. Besides the profligate spending in London, Egypt reactivated a lot of WWII equipment the British abandoned and simply forgotten about after Rommel’s final defeats.

(This Italian Fiat M13/40 tank was captured by Britain in North Africa then forgotten about. The Egyptians reactivated it after WWII. It was destroyed by Israel, as seen above.)

Egypt’s 1940s spending spree accomplished nothing. Some of the complex weapons were difficult for the Egyptian army to rapidly ingest. A lot of the gear was wasted in the bungled 1948 war against Israel, and what remained was annihilated during the Suez crisis.

As far as the United States, it’s hard to believe today but in 1945, the USA wanted to keep American weapons out of the middle east. In November 1947, the State Department and Pentagon developed a policy to limit exports of surplus WWII gear there to inconsequential quantities.

(The Iraqi army of the 1950s featured M115 howitzers towed by M4 tractors, both WWII surplus sold by the United States.) (photo via Life magazine)

(A-26 Invaders were sold to the then-primitive Royal Saudi Air Force.)

Two factors upset the region’s whole planned balance of power. The first, and by far most influential, was Israel’s surprise victory in it’s 1948 war of independence. The second was the fall of pro-western governments: the buffoonish monarchies in Egypt, Libya, and Iraq; along with the first Syrian republic; all overthrown. These were replaced by pro-Soviet governments, which began importing Soviet arms.

(The USSR supplied Egypt with SU-100 tank destroyers, Ya-12 artillery tractors, and A-19 field guns – all WWII systems.)

PART II: PRIVATE ARMS DEALERS AFTER WWII

How private arms deals worked after WWII

Generally, there were three key documents:

♦The export license was critical. This allowed private dealers to move guns out of the country they were bought or stored in. The export license was the hardest to evade, as the leftovers of WWII were typically stored in highly-stable nations: the USA, the UK, Norway, and so on. Granting or denying export licenses is how governments allowed or stopped the flow of privately-held WWII arms.

♦The recipient army’s import license was of course the reverse, it allowed the dealer to legally possess the weapons as he delivered them to. Import licenses were also needed to move weapons around: for example, ex-Wehrmacht 98k rifles bought by an arms dealer in Belgium after WWII and sold to Saudi Arabia through a British port would need both Saudi and UK import licenses, in addition to a Belgian export license.

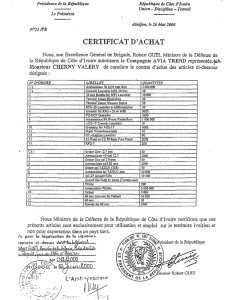

♦The “key” that put it all together was the End User Certificate (EUC). This document certified that the army buying the guns was in fact the same as the dealer was claiming when applying for an export license. EUCs listed the specific weapons and quantities, and guaranteed that they were for that country’s army only and would not end up elsewhere.

In the lingo of the arms trade, an irregular document of this type was called a “bent EUC”. Bent EUCs are what enabled the shadowy side of the trade. Alternatively they allowed governments to arm nations or guerilla groups outside the realms of diplomacy and law.

(An example of a bent EUC. Ostensibly from Ivory Coast, it actually served to move guns from Europe to the warlord Charles Taylor who ruled nearby Liberia from 1997 – 2003.)

After WWII there were several ways to go about bent EUCs. The most crude was simple forgery. Of course this was the easiest to detect; if suspicious the home government simply had to phone the recipient’s embassy before giving an export license.

A more common trick was to get a real EUC, but signed by somebody with no business singing it. It was crystal clear who in Britain or the USA could legally sign EUCs. Less clear was if Congo’s assistant defense adjunct, or a Honduran general, or the brother of a Saudi sheikh, was authorized to do so. Sometimes an export license based on a questionably-signed EUC was granted, and when the error was discovered, the guns in question had already mysteriously vanished. The arms dealer could legally feign ignorance.

The worst bent EUCs were diversions. Here, an arms dealer would bribe an authorized official in one country to get a genuine EUC and then an export license . Once aboard the ship or airplane, the guns never made it there, instead heading to the true buyer. This was difficult for source countries to even detect, let alone stop.

(This bent EUC certified that that a mortar shipping from Austria in 1987 was for Jordanian use. In reality, it ended up in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.)

Nigeria was an “easy mark” for bent EUCs in the 1960s. By the 1970s, it had been surpassed by Zaire, where corruption was rampant. In Zaire’s capital Kinsasha, the only question regarding an EUC was how big the bribe would be. Many weapons used in Africa’s various conflicts had Zairian EUCs – conversely, the Zairian army itself was an under-equipped joke.

In South America, Peru during the Alvarado / Bermúdez juntas (1968 – 1979) was the equivalent. It was later calculated that if all Peruvian EUCs written after WWII had been legitimate, Peru’s army should have been the largest in the southern hemisphere by 1980.

While Franco was still alive, Spain had a reputation on the “other end” of bent EUCs, in that as long as they weren’t flagrantly fake, any EUC signed by anybody from anywhere immediately got an export license. The same in Tito’s Yugoslavia; where customs officials strove to issue as many export licenses as possible, not to monitor end users.

(Ex-German 98k rifles via Yugoslavia, along with the cheaper M-48 postwar Yugoslav copy, ended up on the streets of Beirut in the 1980s. They were usually trasnshipped under bent EUCs via Cyprus, which was a hub of illicit arms.)

Eventually this came to a head. In the USA it was never really an issue; it was exceedingly hard to fool the Pentagon, State Department, and Commerce Department in one swoop. In Britain on the other hand; EUCs were not even required at all until 1969. Prior to that, export licenses were granted on the basis of the weapon’s sophistication, not the recipient country’s behavior. This is one reason so many post-WWII arms dealers (Interarms, Major Turp, etc) operated out of the UK. The free-for-all export mess during the Biafran war is what changed policy in London.

Postwar France was probably the strictest of all. To begin with, private arms dealers had to buy a permit to even negotiate with foreign armies. Once an export license was granted, the dealer had to post a security deposit. This varied with the nature of the weapon: something like a WWII truck might be 20%, while submachine guns were as high as 100%. After delivery to the EUC country, officials from the French embassy there personally inspected the gear and verified that the arms matched the paperwork and hadn’t been diverted. Only then did the dealer get his deposit back. Other countries gradually adopted this system.

(This mercenary-flown Biafran A-26 Invader had belonged to the French air force, and was delivered by a French private arms dealer. The ease by which it evaded France’s strict regimen led many to believe that Paris willfully looked the other way.)

Why did governments allow private dealers?

Deniability: The most “colorful” reason was western governments could arm unsavory allies without the hassle of open debate by elected legislators. In Britain or the USA, arms export licenses were technically also public record, but there were few reporters who wanted to sift through boring paperwork to find them and even fewer people who cared to read about it. A good example is the UK’s wanton issuance of export licenses to African end users in the 1960s….in Parliament officials would have to give public assent for a nation-to-nation sale and then personally answer to voters, but if WWII-surplus weapons were provided by a company like Merex, the license was issued by a faceless bureaucracy. In the case of insurgent groups, directly arming them might be construed as a warlike act, but if funds were channeled through overseas banks and then to a private dealer, the origin was obscured.

Practicality: While shady covert reasons were the most entertaining, the main reason private arms dealers flourished after WWII was simple convenience. The victorious western Allies (and later, nations liberated by them) were drowning in an ocean of weapons after WWII. There was no guarantee it would ever be wanted again (indeed, much never was). It was incredibly expensive to crate up, catalog, store, and guard this gear.

(The US Army’s Brooklyn Depot in October 1949, four years past the end of WWII. It looks like the final scene of “Raiders Of The Lost Ark”.)

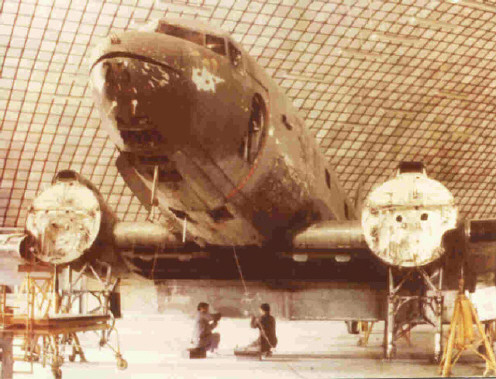

(The federal government had to hire guards for stored WWII weapons, like those at the Belle Mead, NJ warehouse. If guns were sold off to private arms dealers, security became their problem to worry about.)

(During WWII, the US Army’s New Cumberland, PA facility had been a POW camp. After 1945, it was renamed War Reserves Center New Cumberland, and warehoused weapons of WWII, then also later conflicts. Shown here in the 1960s, a WWII C-47 Skytrain is visible as are Vietnam-era CH-47 Chinooks. WWII equipment was here as late as President Carter’s term. This facility, reduced in size, is still active in 2018.)

An alternative was selling WWII weapons to private arms dealers. Besides cash from the sale, it would now be somebody else’s problem to warehouse and insure it all. In theory, the government still held veto over where the sold guns ended up , via export licenses.

This was especially true of ammunition. During WWII, calibers common in 1939 like 6.5mm Dutch and 8mm Nambu simply went extinct; while others like 9mm Parabellum continued on past 1945. A much, much larger category was “zombie” calibers: cartridges which would have very few or no new guns designed for them after WWII, but, there still were many thousands of guns firing them in use with smaller armies during the Cold War. Here the list is long….. 7.62mm Tokarev, 8x50mm(R) Lebel, 9mm Kurz, 8x63mm Patron, 9x25mm, .303 British, and so on and so on.

For Britain, France, the USA, etc with newly-independent post-WWII allies courted as “client states”, there had to be a way to support these legacy guns used by their poorer allies, but it was impractical or impossible to keep stores of these calibers.

The situation exacerbated as the west standardized on 7.62 NATO and the Soviet bloc on 7.62x39mm. Even 7.92x57mm Mauser, the most common military rifle round on Earth in 1939, was relentlessly suffocated by standardization on these two calibers.

(Interarms-repackaged German 7.92mm Mauser ammunition. At one point in the 1960s, the company owned half a billion rounds of various WWII calibers.) (photo via armslist website)

Allowing private dealers to supply allies with legacy ammunition was a viable solution.

Politics: The cost of weapons ballooned after WWII. During WWII a M3 Grease Gun wasn’t particularly expensive. The next generation, like the M14, were more so, and gear behind this, like the M16, even more yet. Weapons manufacturers became dependent on exports to shore up costs of supplying the home military.

In the 1960s the downside for nations still with huge holdings of WWII arms was that they had to talk out of both sides of their mouths. Consider the Pentagon trying to sell new M14s abroad: If the availability of cheaper used M1 Garands was mentioned; Winchester might lose a critical order; but; otherwise government-owned WWII rifles would continue to gather dust. Selling old guns to private dealers eliminated the conflict of interest, at least as far as defense lobbyists were concerned.

types of private sales

♦From stock: Self-explanatory; this was the easiest however few private dealers had the money to maintain long-term inventory.

♦Brokered: Here a private arms dealer located a source of WWII weapons, and simultaneously an interested buyer, then matched them up for a commission. This had to happen very fast, and at the same time as export licenses, and was easier said than done.

♦PIK: Payment-In-Kind, or PIK, was useful for third world countries with weak national currencies. Consider a 1960s African army with leftover WWII Webleys and Enfields, but now wanting modern Spanish jet warplanes: The African nation would ship the WWII guns to a private arms dealer, but received no payment. Instead, the arms dealer would deposit a predetermined sum of “hard” currency (US dollars, French francs, etc) into a Swiss bank. The Spanish planemaker then withdrew the same, and then shipped new jets to Africa.

The hazard to the private arms dealer was that he now had to find somebody else to resell the WWII guns to, in order to cover his cost. The advantage was that often, he could lowball both sides. Poor countries with weak currencies were boxed into a corner, while defense companies gained an easy sale they’d have otherwise shunned.

some notable post-WWII private arms dealers

Major Turp

Robert Turp was an officer in the British army during WWII. After Germany’s surrender, he was part of a team that traveled the British occupation zone examining German guns. He was later the first defense attache to South Korea.

(Major Turp with some of his WWII-era offerings, including a Lewis Gun, a MG-42, a MG-34, a Bren, various types of Enfields, a MP-35, and a QF 6-Pounder artillery piece.) (photo via Life magazine)

After leaving the service he worked out of a firearms reconditioning shop in Bexleyheath, UK; later moving to an office in London. He also had a warehouse in Belgium. Usually just known as “Major Turp”, in particular he sold weapons around Africa (especially Katanga in the 1960s), developing something of a knack for supplying newly-independent nations on the continent. On a more grim note, he also had a knack for exploiting corruption in these new countries. He was attributed the quote “….where arms are concerned, the newer and blacker the country, the greater the graft.”.

(Katangan soldier with a WWII M1919 machine gun. A great portion of Katanga’s arms came via private dealers.)

This did not go unnoticed and in 1966, a petition to P.M. Harold Wilson suggested Britain ban private arms dealers entirely; with Major Turp specifically cited by name as an example why.

Major Turp’s most public moment came when he refused to sell guns to 1970s Rhodesia. While he received accolades, his decision was rooted less in morality and more in self-interest: it appeared at the time that Britain and Rhodesia might come into conflict, and he was concerned about criminal charges that might be brought against him if guns he sold ended up used against British troops.

(Turp later authored a book on the profession.)

Turp’s final notoriety came in 1992. A German arms dealer at the Sheraton hotel in Sofia, Bulgaria contacted Turp and inquired if he’d be interested in brokering a sale of plutonium; presumably to Iraq. Turp declined and notified British authorities.

Interarms

Sam Cummings was born in 1927 in Philadelphia, PA. As a child, he read any firearms-related book he could get his hands on.

Cummings was literally in the first post-WWII generation of the American military, being drafted in 1945 just after Japan’s surrender. During boot camp he displayed technical aptitude and was sent to NCO school at Camp Lee, VA. The instructors were so impressed at his knowledge of the world’s guns, that they simply retained him at Camp Lee.

It was also at Camp Lee that Cummings first dipped into the world of arms dealing. In occupied Germany, American forces were snapping up anything that might be of any intelligence value and sending it back to the USA. The instructions were to err on the side of caution, and send useless gear back rather than miss something of interest. Invariably, along with autocannons and diesels came much larger quantities of junk, of zero intelligence value. In 1946, Cummings found an entire truckload of stahlhelms that the US Army had dumped off outside Camp Lee. Cummings bought the helmets for 50¢ each, sent them to Maryland, and resold them as souvenirs at a 700% profit.

After his enlistment finished, Cummings moved to Washington, DC and used his GI Bill to take business courses. On weekends, he scoured Maryland and Virginia for detritus of WWII which, to his astonishment, was everywhere. The rapidly shrinking American military had so much excess equipment that anything with the simplest flaw was being discarded, and local scrap dealers had no problem reselling if a buyer would pay above the metal value.

In 1948 Cummings took a semester at Oxford in the UK. After exams, Cummings and some friends decided to tour Europe. They started in Denmark and drove southwards. At the Danish border, which now abutted the “Bizone” (the American and British zones merged in 1947), the group was given a travel pass through occupied Germany but told not snoop around. Cummings did anyways and was flabbergasted at the amount of weaponry still visible three years after WWII. The Allies had completed their EOD sweeps and first round of battlefield cleanups, but there were still howitzers, tanks, and firearms all over the place. Moving into France, the group found large gravel piles placed along rural backroads. The postwar French government intended these for local villagers, in that non-explosive items missed during preliminary cleanups could be buried in the gravel, which would later be collected and used as landfill. Instead, most of the French farmers just threw whatever they found into the ditch nearby. Cummings found barely-scratched 98ks and MG-42s.

(A pile of German 98k rifles taken over by Norway after WWII. There were 350,000 98ks in Norway counted in the summer of 1945.)

Returning to the USA, Cummings pondered the potential profit of leftover WWII weapons. None the less, he needed a job, and hoped to get employment somewhere that gun knowledge was useful. Applications to the FBI and CIA were rejected. Cummings settled for a job as a clerk at the Commerce Department. To pass the time in Washington, he sometimes sat in the gallery of Congress, where he learned the boring process of trade licenses.

Five days after the Korean War started in 1950, Cummings was contacted by the CIA, which had kept his resume on file. Two days later he had an interview and was hired.

During the Korean War, Cummings was one of the CIA’s small arms “puzzlemen”. Smashed rifles, spent shell casings, parts of destroyed mortars, etc were shipped from Korea to the USA, where the puzzlemen were assigned to determine what it was and where it came from. The puzzlemen also reviewed (often blurry) east bloc press clippings to try and identify which units of which countries were using which kinds of small arms. For Cummings, the job was both a paycheck and a learning experience, as he had access to the CIA’s full small arms database, and he could freely browse traits of the world’s weapons.

In 1951, Cummings undertook his only CIA field assignment. The CIA felt that there would still be German WWII weapons available in western Europe. Posing as a movie prop agent, Cummings traveled from country to country, buying ex-Wehrmacht firearms which the CIA intended to supply to Taiwan.

After this, Cummings was assigned to the Western Arms project. Originally a commercial endeavor, Western Arms became sort of a shadowy civilian/CIA hybrid. It was intended as an ongoing effort of what Cummings had done in Europe; namely to buy up as much leftover WWII weaponry as possible; with the side benefit that these guns would be untraceable assets for CIA endeavors abroad. A sister company, Winfield Arms, served as a profit-generating conduit for the project.

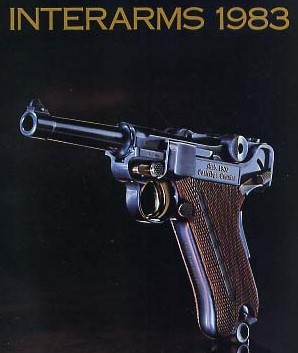

In 1953 Cummings left Western Arms and the CIA, and decided to start his own arms trading business, which he called International Armament Corporation. Originally referred to as “Interarmco”, Cummings had to change it to “Interarms” after a trademark dispute with a steel company.

At the beginning, Cummings took pains to hide that Interarms was a one-man show run out of his kitchen. Mail was routed through a post office box in DC to imply that the company was a big shot with the US government. Cummings own business card listed him as “vice president” falsely implying that there were older and richer people above him.

Interarms first big buy was 7,000 obsolete guns from the Panamanian military, which he bought for $25,000 and resold for a $20,000 profit. Next he scoured western Europe. Compared to his college vacation, by the mid-1950s Europe’s WWII battlefields had been cleaned up, but this now made his task easier – thousands of ex-Wehrmacht weapons, and even some Allied gear, was sitting cataloged in warehouses. For the most part, governments just wanted whatever cash they could get to move aging WWII equipment out of their custody.

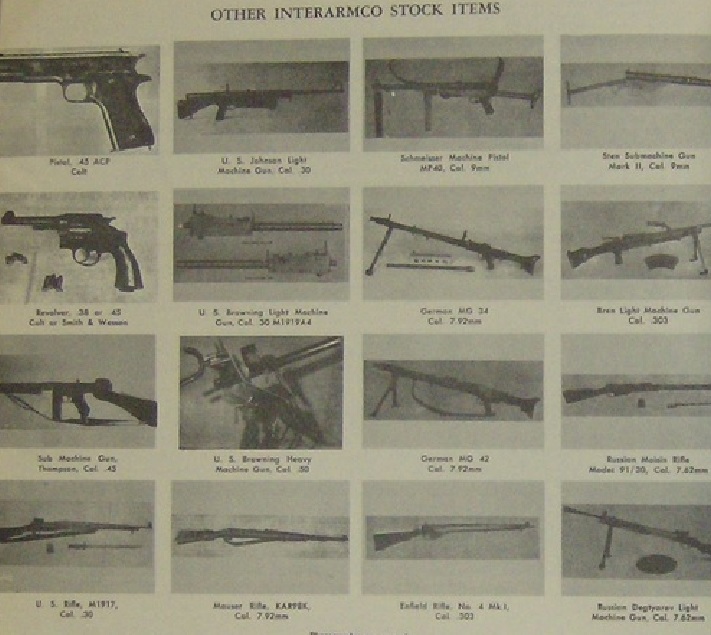

(Interarms in the late 1950s was “who’s who” of WWII: Starting at the top right, M1911, M1941 Johnson, MP-40, Sten Mk.II, M1917, M1919A4, MG-34, Bren, M1A1 Thompson, M2 Browning .50cal, MG-42, Mosin-Nagant M91/30, M1917, 98k, Enfield No4 Mk.I, DP-27.)

(Interarms M1 mortars in the 1950s. This American 81mm weapon of WWII was replaced by the M29 after the Korean War. It was still highly-desirable in third world armies.)

Cummings was the antithesis of stereotypical gun runners; who were either loud brash playboys or shadowy underworld figures. Cummings made no effort to hide himself. He readily posed for photos with mainstream celebrities. He gave media interviews and freely testified to the American and British governments on arms dealing.

(Sam Cummings with his wares in 1966.)

On the other hand, Cummings did not live a foolish lifestyle. After buying his home in Monaco; Cummings shied away from further luxury. He did not gamble, smoke, or drink. He always flew coach on the cheapest airline he could find. Business lunches in Manchester were at a common English pub instead of five-star restaurants.

Cummings was a good businessman. He used a clever cost-averaging method which would incur a loss on guns unlikely to resell on the world military market, but still gain profitable access to the weapons he really wanted.

Interarms sold M1 Garands to Haiti, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, the Philippines, and Guatemala. Other WWII-era weapons were sold to Indonesia, Biafra, Malaysia, Costa Rica, the middle east, and Thailand. Buys came from all over – mainly the remains of WWII in western Europe early on, then Latin America, Israel, Yugoslavia, and even the UK and USA themselves.

(WWII rifles stocked by Interarms in 1959: three types of Enfields, a M1941 Johnson, a M1 Garand, and various bolt-action Mausers.)

Cummings had a knack for “predicting the future” of small arms. During the early 1960s, when future wars were foreseen as high-tech and nuclear, he bought huge lots of WWII-vintage M2 Browning .50cal machine guns from Canada at $25 each. By the end of the decade these were urgently needed in the Vietnam War, and he resold them at a massive profit to the American government. The last of these was sent to Kuwait in the 1990s to rebuild that country’s army after Desert Storm.

Just before Congress’s 1968 ban on importation of military guns into the USA, Cummings packed Interarms’s Virginia location with 700,000 weapons.

In 1959, Interarms bought tens of thousands of Czechoslovak-made vz.24 rifles from Spain; that country’s entire stockpile. The vz.24 was a bolt-action Mauser very similar to the 98k used by Germany during WWII. These had been supplied by the USSR to the republicans during the 1930s Spanish civil war and then warehoused by Franco after his victory. More than likely, Interarms later resold these to Biafra.

(Biafran infantry with Mausers in 1968. Biafra used several variants obtained through private arms dealers….the Czechoslovak vz.98N (a postwar copy of the 98k), the vz.24 described above, and actual ex-Wehrmacht 98k rifles.) (photo via Hulton Archive)

In 1965, Interarms made a huge buy from Spain of all non-standard WWII-era types remaining in storage. These ran the gamut from 98ks to Astras to Enfields to Mosin-Nagants, and even some Tokarev SVT-38s which had been supplied to the republicans in the 1930s. About 250 million rounds of ammunition, in various calibers, was also acquired.

There were a few bad deals. During the 1960s Cummings bought WWII Lahti L-39 rifles from Finland. This beast of a gun fired the 20x138mm(B) AP cartridge, an uncommon ammunition type.

Interarms couldn’t find any military wanting them, and offered them to civilians. After one was used bizarrely in a crime (it literally shot open a safe), Cummings pulled them from sale. By the 1970s, with no orders forthcoming, Interarms gave them away as gifts to clients. In another instance, Interarms bought long-warehoused WWII German grenades from Denmark. Cummings planned to extract the explosive from each, repackage it, and sell it to construction companies through DuPont. This violated safety regulations in Virginia and eventually Interarms just dumped the WWII grenades into the Atlantic.

But overall, Interarms was a massive success. Annual turnover was as high as $100 million, usually at a 10 – 12% margin.

(An obsolete British 18-pounder at Interarms in the early 1960s. In the third world, there was still an appetite for artillery like this.)

Besides the scope of it’s operations, what set Interarms apart was that it was always extremely careful to follow all export regulations. On every single deal through the company’s existence, every i was dotted and every t crossed. On the other hand, Cummings was quick to draw a distinction between the letter of the law and it’s intent. Some Interarms exports ended up in “hot” regions of the Cold War; having gone through all the proper paperwork to start but then later diverted abroad. An example was in the 1960s, when Saudi Arabia quoted 1,000 98k rifles. The kingdom was shopping for new guided missiles at the same time, and had no plausible military need for used bolt-action rifles. Clearly they’d end up elsewhere. None the less, all paperwork was in order and Interarms proceeded with the quote.

Cummings ran Interarms from his home in Monte Carlo, Monaco. He flew to his British operation monthly and to the American location as needed.

In the UK, Interarms headquarters was in Manchester. A six-story warehouse, this building survived the Blitz during WWII. Clues to what was now inside were the armored steel door and security camera above it.

(The Interarms building in Manchester, UK in 1975. This building was torn down in December 1997, shortly before Interarms folded.) (photo by Derek Ralphs)

The Manchester location was almost entirely dedicated to weapons intended for military resale. There was a shooting range inside for test-firings, and workspaces for gunsmiths. At no point were there fewer than 300,000 guns inside. Usually inventory hovered around the 700,000 point. In 1958, Interarms made a mega-deal with the British armed forces (which was getting out of bolt-action rifles entirely) and bought almost the whole remaining WWII Enfield family of guns, about a million. Many were later sold to Pakistan and Kenya. By Cumming’s own calculation, Interarms’s inventory of WWII Enfields peaked in 1960, when the company had 2,000,000 in stock.

(The Interarms USA complex in 1963. Most of these buildings still exist, used for other purposes after Interarms folded.)

In the USA, Interarms had it’s facility at Alexandria, VA. There was a dock for ocean freighters, warehouses with railroad access, “Building Two” (a showroom to impress potential clients), and a special US Customs bonded warehouse. The facility had the world’s largest ammunition refurbishment machine, which automatically retracted and reinstalled bullets into casings. Adjacent was Potomac Arms, a separate entity owned by a former employee of Cummings. Potomac primarily dealt in single-sale guns inside the USA.

(The Potomac Arms building in the 1960s, with some of Interarms’s obsolete artillery holdings in the parking lot.)

(A Ye Old Hunter ad in American Rifleman in 1960. Blocked by American law from importing from Warsaw Pact countries, Interarms acquired Soviet Mosin-Nagants first from Finland, then from the middle east and the Spanish mega-deal. Western governments supporting rebel groups found Interarms useful, as it was a way to use communist arms against communists. Periodic surpluses at Interarms were sold to civilians through Ye Old Hunter.)

The same building housed Ye Old Hunter, a subsidiary of Interarms which sold guns that Cummings couldn’t peddle to military users. The whole operation was quite a sight; especially in the 1960s when forklifts could be seen moving old artillery and crates of WWII ammunition around the grounds. At one point Cummings had M4 Sherman tanks stored here.

Interarms bought M1 Garands wherever possible. The Garand inventory flipped rapidly during the 1960s, with lots constantly coming and going.

The Enfield was always a staple of Interarms, from beginning to end. Besides the early 1950s buys of WWII guns marooned on mainland Europe, and the big British buy at the end of the decade, in 1961 Interarms bought a large lot of Enfield No.1s from Ireland. These had been in the British Home Guard during WWII, then sold to Ireland. Inside Interarms, these were called “Shamrock Enfields”.

(Egyptian female army reservists drill with Enfield SMLEs in the 1950s.)

Axis arms were represented as well. Interarms was still making big 98k buys as late as the 1970s, when 3,000 were purchased from Portugal. German 98ks and Italian Carcanos were available for military customers into the 1980s. Often, Interarms had MP-40s and MG-42s available. After West Germany rearmed in 1955, Interarms enjoyed a sales boon, as the company resold MG-42 parts needed for the MG1 conversion to 7.62 NATO, to the Bundeswehr. These had been Wehrmacht property during WWII, snapped up by Interarms in 1953 from countries formerly occupied by Germany during the war, when it was thought there would never again be a German military.

(Sam Cummings with an ex-Wehrmacht MG-42 at the NYC customs office during the Bundeswehr deal.)

Neutral countries were not overlooked; and a buy of Swedish M/94 rifles was made, most of which were sold in Latin America. One of the oldest offerings was Remington Rolling Blocks which Interarms bought during 1953, and were still being marketed in the 1960s.

(Sam Cummings talks with a gunsmith at his British unit in May 1966.)

Interarms also sold WWII ammunition. One buy was one million rounds of 7.65x53mm Arg. from Argentina in the early 1960s, most of which was peddled off to other South American armies. Cummings calculated that in the first 15 years that Interarms had been in business, it sold 500,000,000 rounds of WWII-era small arms ammunition.

Interarms later branched out from WWII gear. It was an early distributor of Eugene Stoner’s AR-10. One recipient was Fidel Castro. After the communist victory in Cuba, Cummings inquired if Castro was going to pay for a hundred AR-10s shipped there. Castro replied that Cummings should come to Havana and try to collect himself. Cummings did just that, and an impressed Castro paid him. Later, Interarms bought captured ex-Arab arms SKSs and AK-47s, from Israel. By the 1980s, the AK-47 was more common in the Manchester warehouse than WWII Enfields.

Cummings did not have further direct, open involvement with the CIA after the 1950s but did not hide his past either; and seemed to enjoy suspicions of potential clients. His financial subsidiary was called Cummings Investment Associates with the appropriate acronym.

(An article about Interarms in a 1970 issue of Sports Illustrated. Cummings is largely forgotten today, but he fascinated the public in 1960s and 1970s.)

Sam Cummings passed away in 1998. The British operation in Manchester had already closed by then. After the USA’s ban on importation of military hardware, the Alexandria facility shrank in importance. By 1980, some of it had already been shut down.

Interarms completely went out of business in 1999. Potomac Arms continued on, with a surplus store taking over the former Ye Old Hunter space. Potomac Arms closed in 2006, being the last legacy remnant of Interarms.

High Standard bought the Interarms trademark. In 2014, the name was acquired by a small gun parts shop in Houston, TX which has no relation to Sam Cumming’s company.

Crown Agents

These were a not-quite governmental, but not private, auspice of Great Britain. Chartered in 1833 to buy & sell in British colonies, after WWII peddling British weaponry abroad was their main employ.

Crown Agents had broad legal latitude, and often served for the UK to sell WWII-era guns without debate in Parliament. For example, they were used in this capacity to sell WWII-surplus 40mm ammunition to Nigeria during the Biafra war.

(The WWII-vintage anti-aircraft rounds sold to Nigeria.)

As late as the time of President Ford, the USA considered Crown Agents to be sovereign entities, as if they were countries.

Crown Agents answered to a central office in London. They increasingly became involved not in direct dealing, but rather financing weapons deals. In 1967 an entity called Millbank was founded specifically to finance arms deals. Millbank was £2 million in debt by the 1970s. It was also accused of being a conduit for bribes. Millbank proved the final downfall of the Crown Agents. Bankrupt by 1979, Millbank was absorbed by the UK’s Ministry of Defense while the rest of the Crown Agents subordinated to the British government, losing their unique status. In 1996 the former Crown Agents central office was spun off as a purely commercial company, offering assistance with civil engineering, and the whole system came to an end.

Merex

Interarm’s main rival was Merex AG, a company founded by Gerhard Mertins. During WWII, Mertins had been a Fallschirmjäger (paratrooper) in the Luftwaffe. After WWII, Mertins bounced around the middle east as a freelance military advisor, at one point supervising training of Egypt’s airborne troops.

Mertins’s greatest assets was his connections. He belonged to the “Green Devils”, a club of Fallschirmjäger veterans. Many of these men went on to postwar civilian careers with West German companies having branches abroad, and knew how foreign customs bureaus operated. One of Merex’s key employees was Gerhard Bauch, who had been a captain in the Wehrmacht and later a tradesman in the middle east.

Merex was a Swiss company but de facto in West Germany. By the mid-1960s it’s field offices spanned the globe: Bethesda, MD in the USA, and less savory locations like Damascus, Bogota, and Karachi. Mertins was friends with Willem Sassen, a former Waffen-SS soldier who moved to Argentina after WWII. In 1960, Sassen was recruited as Merex’s South American representative. Sassen was close to Chile’s Pinochet and Paraguay’s Stroessner, and opened up a huge market to Merex for WWII-era weapons.

In the 1960s Merex and Interarms cooperated. Later the companies had a falling out, with Mertins disparaging Sam Cummings as “that scrap metal dealer” and so forth.

Merex somewhat lived up to the romanticized version of private arms dealers. The company was intertwined with the BND (West German intelligence service), sometimes while simultaneously being investigated by other West German agencies. Mertins dealt with the lowest of the low; be it Arab governments, African rebels, South American strongmen, or whomever. Merex had no qualms arming both sides of a conflict: Pakistan and India, Iraq and Iran, etc.

(A Pakistani militia with WWII SMLEs in 1965.)

After the Cold War, Merex’s importance waned. Mertins died in 1993, and by the latter part of the decade Merex had faded away. The 21st century defense company Merex has no relation.

“The Black Eagle of Harlem”

Hubert Julian was an interesting post-WWII arms dealer. Born in 1897, he was notable for being a middle-class black man in a profession dominated by wealthy whites.

Julian was one of the first black pilots in the USA, hence his nickname. After a failed attempt to join the Finnish air force as a mercenary, he decided to try his luck in selling weapons. During the 1950s, Julian sold WWII-era guns to Cuba, Guatemala, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. He was one of the few American private arms dealers to broach the Iron Curtain. In 1955, he bought a load of arms from communist Poland, sight unseen, and successfully sold them to Guatemala. They turned out to be useless junk. Later, he was said to have dealt with Czechoslovakia.

Many of Julian’s weapons endeavors were failures. He had a steep (30%) commission, and lacked both the operating capital of Interarms and the connections of Merex. He was also indiscreet, and once bragged about carrying $1,000 bills in his wallet when that denomination was still in use.

In 1960, Julian flew to Kinshasa (Léopoldville at the time) and met Patrice Lumumba. Julian told the latter that Congo should have an air force flown by black pilots, and he was available to be the first. Lumumba did not take him up on his offer. A year later, Julian flew to Elisabethville, the capital of Congo’s breakaway Katanga province, intent on selling WWII Sten Mk.II submachine guns which he had sourced in Europe.

Traveling as a “mining executive”, Julian landed in Elisabethville and was met by Indian troops of the UN contingent, who had in the meantime secured the airport. Julian’s luggage was searched. His checked bags held a Sten and 400 rounds of ammunition. In his briefcase was a contract for 3,200 Stens, 5,000 pistols, and two million rounds of ammunition ranging from 9mm to artillery calibers. To top it off he was, for whatever reason, carrying a WWII gas mask. Congo’s government wanted him executed, however the UN released him, ordering him to retire from arms dealing.

As this was happening, the FBI became suspicious of four WWII A-26 Invaders being serviced at O’Hare in Chicago and Newark International in New Jersey. The A-26 popped up throughout the Cold War, as it was an incredibly durable design, easy to fly, and readily available as demilitarized airframes in the 1950s. These four were traced to a deal Julian was working on, to sell them to Katanga. Julian was not charged with any crime, but these WWII bombers never made it to Katanga.

(Katanga’s short-lived 1960s air force was mostly black market WWII types or impounded airliners. This Harvard Mk.III (Britain’s lend-lease name for T-6 Texans) was flown by a mercenary.)

Julian laid low for a while but by the early 1970s, was back at it again in Africa, now selling both WWII-era and more modern weapons. In 1974, the FBI discovered his grandest folly of all, an insane plan to buy F-104 Starfighter supersonic jets from West Germany and sell them on the black market. No charges were filed due to his age (77 at the time) and the absurdity of the scheme.

Julian’s last deals came at the start of the Lebanese civil war in 1975 -1976. It’s not known for certain that he was involved; one report said his name was being used as an alias by another arms dealer in Beirut. Thereafter he led an extremely quiet life, passing away in 1983.

an example: the Favier fiasco

In 1966, an arms dealer named Paul Favier (a former officer in the French police) came into ownership of a warehouse in the Netherlands with 3,600 M1A1 Thompson submachine guns. These had been transferred from the US Army to the Dutch upon Germany’s surrender. Later they were bought by Israel, which decided they’d be more of a hassle to ship out of Europe than they were worth. They had remained in the warehouse ever since. In 1965 a Tel Aviv arms dealer who simply went by “Arazi” sold the guns to Favier.

A Nigerian diplomat in Europe named Matthew Mbu; an ethnic Ibo from the Biafra region; caught wind of the deal and contacted Favier. Still a year before from Biafra’s secession from Nigeria, he wanted to arm fellow Ibos for any possible upcoming conflict against his own government (essentially, treason). Mbu wanted Favier to fly the Tommys straight to Port Harcourt in Nigeria, where the customs officials were almost all Ibos and would look the other way. Favier was interested but said this route was impossible, as there was no way the Netherlands would allow a planeload of guns to Nigeria.

(Biafran M1A1 Thompson)

Favier’s biggest obstacle was getting an export permit out of the Netherlands, and his solution was going to be Major Turp in the UK. Previously, Favier had hired Turp to refurbish a small lot of junked WWII M2 Browning .50cal’s. Favier then brokered deals to sell them around Africa, using British export licenses secured by Turp. Proceeds from the M2s were divided; Turp covering his refurbishment and licensing costs and Favier keeping the rest.

To get the Tommys from Holland to Africa, Favier hatched a scheme where he requested Turp refurbish them in the UK. Turp, who thought the deal was legitimate, agreed and properly drew up a contract and secured a genuine British import license. With these two documents in hand, Favier had little trouble getting a Netherlands export license.

But Favier never had any intention of actually sending the guns to Turp. Instead, for $14,000 cash, Favier hired Hank Wharton. He was a pilot who flew for “U.S. Airways” (not the same as the American airline), an operation which had air-dropped WWII-era guns into Algeria and was now branching out. Wharton’s plane was a DC-4 which he claimed to have bought as surplus from the Burundi military. This DC-4 was already regarded as suspicious in Europe, but Wharton had some sort of scam running with the Burundi government, where that country’s embassies would vouch for it. Privately, Wharton told people he had stolen the plane to settle a debt, without elaborating.

Turp’s contract was written for three batches, so only 1,007 Tommys were aboard. Favier also hid on the plane 2,000 boxes of WWII-surplus ammunition not in the contract, pushing it a ton overweight. Wharton presented both the Dutch export and British import licenses, along with a flight plan to Birmingham. As everything was in order, customs at Rotterdam airport had no choice but to allow the DC-4 on it’s way. The DC-4 made radio contact with the tower at Birmingham so it would get entered into British air traffic control logs, but then turned and instead flew to the Spanish island of Majorca, where it was refueled. It quickly took off again and refueled a second time in Algeria, filing a new flight plan to the Chadian capital of N’Djamena. Wharton became lost over the Sahara and ran out of fuel over Cameroon. The DC-4 made a crash landing, spilling a thousand submachine guns over a field. Under Cameroonian law at that time, the most Wharton could be charged with was misdemeanor possession of a weapon, which was a 30-day jail sentence.

The whole episode illustrated how private arms dealers could circumvent export controls in the decades after WWII. Had Wharton’s plane not crashed, Favier would have almost certainly gotten away with his plan. All of his licenses were legitimate, and the flight was recorded outbound from Holland and inbound to the UK. To have been “found out”, somebody would have had to piece together that Wharton never actually unloaded in Birmingham.

how weapons moved around

Often overlooked is the actual physical transportation of exported gear.

For nation-to-nation sales, it was simple. Goods shipped on civilian freighters but under government paperwork. Sometimes the selling nation’s own warships were used, making it even more clear-cut.

(The WWII-veteran USS Windham Bay (CVE-92) delivered France’s order of surplus F8F Bearcats to Saigon during the Indochina War.)

For private sales the situation was more complex. If possible, air transportation was used. It was more expensive but delivery (and thus, payment) to the seller was much faster. There was greater flexibility as to where the delivery could originate from, and terminate at.

Often this was impossible, either due to the shipment’s size or the buyer’s budget. Sea transportation was slow (an average of 6 weeks to 2 months), and the origin port had to have a customs office familiar with arms export documents.

Private arms dealers naturally tried to keep outbound goods quiet. This was less for security and more for business; arms dealers were a small community and nobody wanted the others to know who was selling what where. Surprisingly it was rare that anybody would try to stop a shipment in progress.

In 1954, the CIA became aware that Czechoslovakia’s Omnipol concern had sold ex-Wehrmacht 98k rifles to Guatemala, and that they were on a merchant ship called S.S. Alfhem.

As part of it’s “PBSUCCESS” project, the CIA considered trying to sink Alfhem en route. This was eventually decided against. However, once moored in Central America, a P-38 Lightning flown by a mercenary pilot tried to bomb it pierside. Instead, the wrong ship, the British merchant S.S. Springfjord, was sunk.

Guatemala and 98ks came up again in December 1983. While searching a merchant ship named M/V New Orleans, US Customs officers in Miami, FL inspected crates labelled “General Cargo – Eagle Exports, Ashdod Israel”. They were full of ex-Wehrmacht 98ks. As the cargo was not slated to tranship on American soil, the New Orleans was sent on it’s way to Guatemala.

The most complex situations for private arms dealers were deliveries into “hot zones”, where cargo would be physically endangered by ongoing combat. It was exceedingly hard to buy insurance for such a delivery, whether by air or sea. Depending on the political situation, and the nature of the export license and EUC, it may have also been illegal. Here, the stereotypical “gunrunner” took over, transhipping the cargo at one location and taking it to the buyer.

(The American pilot Ron Archer was famous during the Biafran War for his daring deliveries of arms and ammunition.)

HOW IT ALL ENDED

In May 1966, Sam Cummings said that he gave the market for WWII firearms another ten years. This was very accurate. The twilight started around Saigon’s fall in 1975. By then, there were already tribesmen in Africa carrying black market FN FALs while secondhand AK-47s spanned from Havana to Luanda. In upcoming conflicts, the fates of Beirut and Managua would be settled by RPG-7s and M16s, not musty crates of Enfields.

fall of the post-WWII private armsmen

Success stories like Sam Cummings were a microscopic fraction of this profession in the decades after WWII. Only slightly larger, but still very few, were men who ended up in jail or dead. The vast, vast overwhelming majority of people who tried their hand at reselling weapons of WWII, simply failed financially. For one, it was a difficult industry to break into: In 1965 Interarms controlled 83% of the private WWII-era arms trade, Merex about 14%, and everybody else roughly 3%.

(The Congo river basin was abuzz with private arms dealers during the Cold War. Any of them dumb enough to accept Katangan Francs lost their shirt when that currency became worthless in January 1963.)

Entrepreneurs in the 1950s thought that dealing WWII arms into the third world would be easy cash. Instead they found themselves immersed in license request fees, insurance premiums, customs paperwork, and freight waybills. Many exhausted their startup funds without completing a single deal.

(By 1981, public attitudes were changing.)

The horrors of Biafra were followed by the start of a similar nightmare in Lebanon. The public no longer thought it was beneficial to have private businessmen fueling new wars with the guns of 1945, and regulations tightened significantly.

A related problem was financing. There was always a lag, called “carry” in the profession’s lingo, inbetween the time a dealer bought WWII guns and the time he received payment for his sale. Shipping by ocean, guns took up to two months to be delivered. “Carries” were covered by “bridges”, short-term loans to allow the dealer to pay the original seller before his buyer took delivery. Payment itself was the “LC” (Letter of Credit); here an independent bank pledged the money unless a two of the three parties (dealer, bank, and buyer) agreed that the sale was fraudulent. After the Iran-Contra Scandal, many banks decided to simply cease offering “bridges” and LCs to arms dealers, even if everything was legitimate.

The developing world was no longer at the mercy of private dealers either. In 1946, there were three countries exporting arms on a nation-to-nation basis. By 1949, four more had joined the club. By 1966 there were fifteen, and by 1976 this had doubled yet again. In 1977, Sam Cummings bemoaned that in the 1950s South Korea had approached him to buy WWII-era rifles, but now, the country itself was selling the same.

Ironically, Sam Cummings enjoyed his greatest mainstream fame when Interarms was already on the wane. In the 1980s he was more of a sage emeritus of the profession’s golden age, than any big asset to the world’s armies.

If the fall of Berlin in 1945 was one bookend for the business, the other was the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. In 1992, Interarms was selling used AK-47s for £79 (about $150) and was still unable to compete with the flood spewing out of the defunct Warsaw Pact…..Poland was selling factory-new AK-47s for $135. As for WWII weapons, the market dried up completely. Whether accredited army or rebel force; there was no impetus to buy bolt-action Mausers when AK-47s were so cheap.

By the end of the 1980s, Merex AG was unprofitable. The company was offering creditors real estate in West Germany instead of money. In 1990 it restructured with outside partners and a focus on the post-Desert Storm Persian Gulf, then the calamitous wars in Africa: Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Liberia. This bought the company a few more years of life but just like it’s rival Interarms, the gig was up.

A new generation was already in the wings. Men like Adnan Khashoggi and Viktor Bout worked out of the middle east and the collapsed Soviet Union, where regulations were non-existent. These dealers had no time for WWII’s weapons, now half a century old, and instead sold shoulder-fired missiles and high-performance machine guns.

the last nation-to-nation transfers of WWII guns

When Sam Cummings took his vacation in 1948, the quantity of WWII-era weapons in Europe and America seemed a bottomless ocean. By 1978, the ocean had indeed been largely drained, through three decades of sales, grants, and periodic spurts of scrappings. The UK and France were almost devoid of WWII-era arms by then.

(This box of .30-06 Springfield ammo is of a 1945 production lot, inspected and relabeled in 1986. The Pentagon failed to find an overseas buyer and it wound up sold below cost into the USA’s recreational market.)

In the USA, President Gerald Ford took office in 1974. Himself a no-nonsense WWII veteran, Ford was determined to trim waste at the Pentagon and identified holdings of 1940s weapons as such. His attitude was that if buyers for WWII minesweepers and half-tracks hadn’t stepped up, they’d missed the boat, and ordered WWII arms scrapped and their emptied warehouses sold as real estate.

An unintended result of Cold War sales of WWII weapons was a “capability trap” that some customers found themselves in. Guatemala is a good example. During WWII, it acquired a squadron of P-26 Peashooters, by then obsolete compared to the P-51 Mustang. In 1954, the Peashooters were replaced by WWII-surplus P-51 Mustangs, themselves now obsolete. By 1973, these were worn-out but Guatemala could now not afford any fighter of any type to replace them. Guatemala has had nothing guarding it’s airspace since.

(In 1995, Guatemala upgraded it’s last dozen WWII M8 Greyhound armored cars with Allison automatic transmissions and commercial diesel engines. It can’t afford replacements yet has to keep spending money to keep these WWII dinosaurs going.)

(In 2013, the Guatemalan army still had 233 Tommys in service. As each generation of firearm gets more expensive, it buys smaller quantities, meaning older generations stay in service.)

Another factor, mentioned earlier, was the conflict between a country selling newly-made arms to support industry vs selling surplus weapons in government warehouses. By the 1960s this was irreconcilable. Companies like Northrop were now national emblems; and embassies in Bonn, Tokyo, and Tehran were acting as de facto salesmen for these companies. Voters cared little about the FMS ledger of available used arms, but cared a lot if a defense contractor laid them off for lack of export orders.

In the Soviet Union, the supply never dried up, but by the 1970s, nobody wanted T-34s or PPSh-41s anymore. A goal of the Kremlin’s arms sales policy (sometimes called “MiG diplomacy”) in the 1950s and 1960s was to sway developing countries into communist fealty. This did not always work. Certainly, lands like Cuba or Guinea became addicted to cheap Soviet guns and became puppets politically. Other countries simply took subsidized WWII guns in the 1950s and then paid lip service to marxist precepts afterwards. When Iraq, Libya, or whomever needed new weapons, they demanded Moscow send them something high-tech, otherwise they’d start shopping from “class-warfare enemies” in the capitalist world.

(The Russian Federation still had stockpiles of captured MG-34s awaiting possible export as late as 2013.)

By the start of the Yugoslav wars in the early 1990s, it was all over. A few conflicts, notably the Syrian Civil War, have featured WWII weapons but getting them, and keeping them fed with ammo, is now considered a liability more than an asset.

(Sometimes, there just is no simple explanation….these rusting Imperial Japanese Army Type 98 grenades were found during an illegal weapons sweep on the Dem. Rep. of Congo in 2015. How they got there is anybody’s guess.)

Reblogged this on Brittius.

LikeLike

My father, who was stationed in the Middle East with the RAF immediately after the war, often spoke of British fighters (Tempests and the like) being shot down by ex RAF spitfires sold legally or otherwise. Sadly the sales of ex military hardware wasn’t always completed wisely.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of the best entries yet. A nice overview of postwar use of WW2 arms. I remember seeing the Interarms warehouse in Alexandria as well as Potomac Arms in the 1980s. The latter still had a rusting assortment of old artillery pieces, a Nebelwerfer, I think, and some very obsolete French anti-tank guns and a small ship’s deck gun, as I recall.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I would love to go back in time with a few hundred bucks. It would be like a kid in a candy store.

LikeLike

very well-researched

LikeLiked by 1 person

Relevant internal links:

Western Arms/Winfield:

https://wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2016/11/06/postwar-advertising-legacy-of-wwii/

The Czech Connection:

https://wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2017/02/20/cleaning-up-after-wwii/

https://wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2015/09/27/stg-44-in-africa-after-wwii/

https://wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2017/06/27/syrian-civil-war-wwii-weapons-used/

S.S. Alfhem, PBSUCCESS, Israeli 98k’s to Guatemala:

https://wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2015/12/14/german-98k-rifle-in-israeli-service/

PBSUCCESS, Guatemalan P-26 Peashooters:

https://wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2016/09/30/the-last-peashooters/

Katanga/The Congo:

https://wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2015/06/29/wwii-weapons-with-force-publique-in-the-belgian-congo/

M1 Garands in Haiti:

https://wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2015/06/09/uphold-democracy-1994-wwii-weapons-encountered/

A-26 Invader:

https://www.google.com/amp/s/wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2017/05/29/1980s-drug-war-wwii-gear-used/

Bearcats in Indochina:

https://wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2015/07/22/f8f-bearcat-post-wwii-service/

LikeLike

Sam Cummings and Major Turp would be great candidates for either serious documentary or a Hollywood movie.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great primer, I remember the Crown Assets in Calgary with a Sherman and a Centurion parked out front. As cadets at Banff it was a pilgramage:) Never thought all that stuff would be gone one day.

One of my favorite sites and I have been on the net since 86.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“the buffoonish monarchies in Egypt, Libya, and Iraq”. I can’t talk to the monarchies of Libya and Egypt. But the Iraqi Monarchy was hardly baffoonish. The founder of the dynasty was King Faisal I, a sophisticated and dignified figure. The last king, Faisal II – murdered by the Iraqi Army in 1958 – was a mere youth when they killed him. The real baffoon of the story was the dictator Kassim who overthrew the Iraqi Monarchy. His record speaks for itself.

LikeLike

Actually, pic of Mongolian with MP40 isn’t from late 1940s.

This photo was taken in 1943, at the ceremony for transaction of tanks built with Mongolian fund to RKKA.

https://orientalist-v.livejournal.com/995027.html

LikeLike

Very interesting and well researched article. The post-war use of WW2 weapons, especially German weapons, is very interesting to read about, especially artillery like the PaK40, FlaK36 etc.

(However, you use it’s (=it is) a lot instead of the possessive pronoun its. This makes the text a bit hard to read actually.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear jwh1975,

I read your 2016 two-part series on mothballing Navy ships and was immediately impressed. I am conducting some research on the same subject and would be honored to discuss the topic with you. Would you be willing to do so?

Thank you, Tony.

PS – Please forgive me for hijacking this comment thread; I could not comment on the 2016 article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

yes no problem

LikeLike

A very enjoyable article, the high level of detail (as always) is most impressive. This article made me think of two things:

1. The novel “Dogs of War” (Forsyth, 1974) which spent a lot of time explaining the EUC and export licenses and subterfuge to get the WWII weapons for the protagonists’ mercenary venture.

2. My Walther P-1 pistol which my dad bought me in 1986. It’s 1974 production and came in a rust-colored cardboard box with big Interarms, Alexandria VA markings. I fired it most recently just a couple months ago. I remember thinking, at the time, “this Interarms company must have a lot of cool stuff!”

LikeLiked by 2 people

Once again a very informative article. You should write a book on this topic.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very interesting read. Interestingly enough those left-over WWII guns would now be worth a pretty penny on either the sportshooter/re-enactor market or deativated on the general collector’s market. A lot more than any backwards military would/could pay for them, if there still is one that would be interested.

LikeLike

Always a great read . . . took me a while and I’ll probably have to re-read it once or twice.

Thanks for the thorough write-up.

LikeLiked by 1 person