Formerly one of Great Britain’s eastern African colonies, Tanzania used WWII-era equipment throughout the later 20th century including a late-1970s war against Uganda.

(Mt. Kilimanjaro is the highest point of Africa and the only part of Tanzania to receive snow. East Africa Railways continued in dwindling existence after WWII, including the wartime Garratt steam locomotives. The defunct company’s rail lines were a great logistics asset to Tanzania during the 1978-1979 Kagera war.) (photo via internationalsteam.co.uk website)

(WWII-vintage PPSh-41 submachine gun of the Tanzanian army.)

Tanzania at a glance

Tanzania was originally part of Germany’s Ost-Afrika colonies. Ceded to Great Britain in 1919, the large mainland portion was governed as a colony called Tanganyika. The two offshore islands of Zanzibar were a separate entity, ruled by a local islamic sheikh as a protectorate of the UK.

(The “blue giraffe” flag of Tanganyika between 1919 and self-rule in 1961.) (Mr. Clay Moss collection)

(The flag of Zanzibar up until the events of 1964.)

In 1954, Julius Nyerere formed the TANU political party advocating for Tanganyika’s independence. In 1961 Tanganyika became a self-governing nation within the Commonwealth and on 9 December 1962, became a fully independent republic.

As for Zanzibar, it had never formally been a part of the British Empire and on 10 December 1963, the UK unilaterally ended any relationship with the sheikh effectively making the islands a (short-lived) independent nation.

the K.A.R. and the “first” Tanganyikan army

Like other ex-British colonies in eastern Africa, Tanganyika’s new army was formed from the colonial King’s African Rifles.

While still a colony, Tanganyika was unique in the K.A.R. in that originally in 1919, the League Of Nations stated that as part of the territory’s transfer from German to British control, it was forbidden for the British to draft natives for military use outside the territory. The 6th Battalion, King’s African Rifles, was specifically formed in Tanganyika for this reason. It was special in that natives from Tanganyika could serve nowhere else, but, African troops from other British colonies could join as well. As WWII approached in 1939 the restrictions were relaxed and after the war started, ignored altogether.

(WWII British poster showing African, Indian, Boer, New Zealander, Canadian, Australian, and English men serving the empire. The reality was somewhat different, with the Indian forces facing discrimination and the black troops, even more.)

During WWII, the only real military activity of the K.A.R. inside Tanganyika itself was the rounding up and internment of the small number of ethnic Germans left over from the Ost-Akrika era (for some, it was their second internment by the British). All units of the K.A.R. served outside the territory; first in the campaign in Italian Somaliland (today Somalia), then the liberation of Ethiopia, and finally in the CBI Theatre against the Japanese.

(A K.A.R. unit during WWII, equipped with the Mk.II Tommy helmet and SMLE Mk.III* rifle; both of which would be carried over into the postwar world and then independent Tanganyika.)

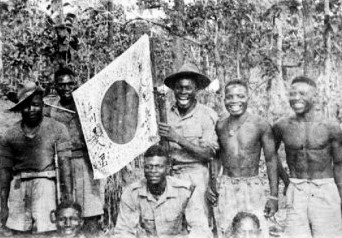

(K.A.R. soldiers on the Burmese front pose with a captured Japanese flag during WWII.)

At it’s height during WWII, the King’s African Rifles comprised 43 infantry battalions, the East Africa Artillery regiment, and a small armored car unit. K.A.R. units were spread out from Madagascar to Somalia to Burma.

(The WWII medal and K.A.R. Long Service medals awarded to British African troops.)

after WWII

After Japan’s 1945 surrender, the K.A.R. downsized to eight battalions, each assigned to a specific part of British eastern Africa. Of these, the 6th and 26th Battalions were assigned to Tanganyika.

The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Battalions (based in Nyasaland and Kenya) deployed to Malaysia from 1948-1959 as part of the “Malay Emergency”. As such, they were re-equipped with more modern weapons compared to K.A.R. units in Tanganyika.

(A K.A.R. unit in Nyasaland after it converted from the WWII Sten gun to the postwar Sterling.)

(A K.A.R. unit in Tanganyika during 1956, equipped with WWII-vintage Enfield bolt-action rifles.)

In 1957, Queen Elizabeth II renamed the King’s African Rifles to East African Land Forces. There was an attempt to keep the force intact as the various colonies moved closer to independence, for example the battalions in Nyasaland (today Malawi), Northern Rhodesia (today Zambia), and Kenya maintained a unified structure across their borders.

(The colours party of the East African Land Forces in 1958. The K.A.R.’s name change did little to improve career opportunities for the black enlisted soldiers.)

None the less, the force had no future. As member colonies became independent, they used EALF battalions on their territory as the nucleus of their new armies.

Tanzania’s “first” army and it’s WWII-era weapons

The 6th and 26th Battalions of the EALF formed the core of newly-independent Tanganyika’s army in 1961. Of all former colonial battalions, these two infantry units were perhaps the two most poorly-equipped, still having almost exclusively WWII-vintage British weaponry.

(The two standard firearms of Tanganyika in the early 1960s: the SMLE Mk.III* and the Enfield No.4 Mk.I; both of the Lee-Enfield family of bolt-action rifles and WWII-vintage.)

(Both rifles fired .303 British, a 7.92x56mm(R) cartridge. In it’s WWII Mk.VII version, this cartridge was 3.075″ long overall and had a 174gr FMJ spitzer bullet.)

The SMLE (short-magazine Lee-Enfield) Mk.III* was originally a British weapon of WWI, still in service throughout WWII and after. It was 3’8″ long and weighed just under 9 lbs. The * in the designation indicated simplified production, with features like the volley-fire sight deleted. It had a 10-round internal magazine, top-loaded via two 5-round stripper clips. Muzzle velocity was 2,441fps and the SMLE had an effective range of about 550 yards.

(SMLE Mk.III* with P.07 bayonet) (photo via oldbritishguns website)

The “snubby” look to the front of the SMLE (carried over from the original Enfield Mk.I) was the result of an early 1900s study to see if removing the bayonet mount from the barrel could improve accuracy.

(Rear sight of an Enfield No.4 Mk.I rifle.)

The Enfield No.4 Mk.I was the standard British service rifle during WWII. It was more strongly built than the SMLE, and returned to a classical layout with the barrel protruding (despite this, it was actually a fraction of an inch shorter overall). It was slightly heavier than earlier Lee-Enfield family members, which alleviated the .303 British’s stout recoil a bit – though not much, and the brass buttplate did not help. The rear sight was moved closer to the shooter and graduated out to 300 yards, with a secondary sight going out to 1,300 yards.

The No.4 Mk.I shared the ammunition and characteristics of the older SMLE. It was the main service weapon that Tanganyika gained upon independence. The national police force also used some, alongside SMLEs. Zanzibar’s small army also used both rifles.

The standard handgun at the time of independence was the Webley Mk.IV revolver, chambered in .38/200 which was very similar to the USA’s .38 S&W round. The more famous version of the Mk.IV, (the .455 British caliber) had been retired two years after WWII ended but the .38/200 version was kept in service around the rapidly-shrinking British Empire as there was a huge glut of that ammunition left over from WWII. This double-action six-shooter had a 620fps muzzle velocity and was accurate out to 55 yards.

The only machine gun inherited from the British at independence was the famous Bren of WWII. Tanganyika had two of the WWII versions, the Mk.II which omitted the shoulder strap and bipod height adjustment, and the Mk.III which was 5 lbs lighter and intended more for use in the Pacific theatre. Both fired the .303 British round at 2,440fps muzzle velocity from a detachable 30-round box magazine at 500rpm, and were air-cooled.

Tanganyika did not inherit any tanks, artillery, or anti-aircraft weapons at independence. A small number of Sterling submachine guns were in use; they being the only post-WWII firearm in service.

naval forces

Newly-independent Tanganyika started without a navy in 1961. In 1952, Great Britain formed the Royal East African Navy to replace WWII-era Royal Naval Reserve stations in the colonies. Similar in concept to other Royal ___ Navies in the Commonwealth; it would be funded by taxes in it’s constituent members (Uganda, Kenya, Tanganyika, and Zanzibar) with warships seconded from the Royal Navy, commanded by white Royal Navy captains and crewed by a mixture of local recruits. The GHQ was in Mombasa, Kenya.

(Ashore flag of the REAN, showing the Union Jack, Kenyan lion, Ugandan crane, Tanganyikan giraffe, and a dhow of Zanzibar.)

(HMS Loch Fada during WWII.) (Imperial War Museum photo)

(Shakesperian class ASW ship.)

The idea never really got off the ground. The largest ship was HMS Loch Fada, a WWII-veteran frigate technically not part of the force but dispatched to Mombasa to jump-start it; and a handful of nearly worthless types such as HMEAS Rosalind, a WWII-veteran Shakespearian class escort, basically a fishing cutter equipped with depth charges during the height of the u-boat menace.

(Dar-es-Salaam remained an important seaport after WWII. Here is S.S. Modasa of the British India Steam Navigation Company arriving in 1947. It was still painted overall black, which the company’s freighters wore during WWII as a nighttime measure against submarines.) (photo by Simon Skudder)

(Dar-es-Salaam remained an important seaport after WWII. Here is S.S. Modasa of the British India Steam Navigation Company arriving in 1947. It was still painted overall black, which the company’s freighters wore during WWII as a nighttime measure against submarines.) (photo by Simon Skudder)

(HMS Ceylon at Dar-es-Salaam before the Korean War. This WWII cruiser was later sold to Peru and served until 1982.) (photo by Ron Bullock)

As the members neared independence, the idea fell apart. Uganda is landlocked and got no benefit from it, Zanzibar was freeloading on the program, and the other two members wanted their own navies. The Royal East African Navy ceased operations in December 1961 and disbanded in June 1962. It’s assets were either transferred to East African Railways or sold; the old HMEAS Rosalind being auctioned to a scrapper for just £214.

Tanzania did not start a navy until the end of the 1960s, with Chinese assistance.

air forces

As part of the Empire Air Training Scheme during WWII, white colonists in Tanganyika and Zanzibar could volunteer for the RAF, with their training done in Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe). There was little RAF activity in Tanganyika itself; due to the fact that the colony faced no threat of air raids. Some airfields used by Shell Oil before WWII started were taken over, and the RAF built a small number of airstrips as stopover points.

(A semi-official button worn by RAF personnel in the colony during WWII.)

(RAF Tabora was an unprepared grass airstrip of the RAF in central Tanganyika. During WWII the South African Air Force modernized it; asphalting the runway. The RAF ceased using it in 1945 but maintained a skeleton presence until 1961. This 1953 photo shows a Venom fighter laying over at Tabora during it’s ferry to Rhodesia. After Tanzania became independent the facility was renamed Base #202. By the 1990s the runway had deteriorated back to gravel. None the less it is still used in 2017 by aircraft with rough-field ability.)

Whatever minor resources the RAF still had in Tanganyika were withdrawn in 1961 and the new country started it’s life with no airpower whatsoever. Internal transport needs were met by contracting airlines.

(An ex-RAF Dakota (lend-leased C-47 Skytrain) of East African Airways at Zanzibar IAP in 1958.) (photo by Jim Dixon)

(An ex-RAF Dakota of East African Airways at Nduli airport near Iringa, Tanzania in the 1950s or 1960s.) (photo by Geoff Pollard)

original force structure

(Tanganyikan soldiers with Enfield No.4 Mk.I rifles shortly after independence. The old K.A.R. uniform, including fez, was retained at first.)

In it’s original guise, Tanganyika’s army was two light infantry battalions, simply numbered 1st and 2nd. Immediately after attaining independence, it was realized that the WWII-era bolt-action rifles were inadequate for modern warfare, and a number of FN FAL assault rifles were bought to supplement the Enfields, plus a handful of FN GP-35 semi-auto handguns to begin replacing the Webleys. Separately, a buy of H&K G3 assault rifles was made from West Germany. The latter turned into a fiasco as the final cost ballooned well over budget, and soured the army on any further gun deals with the West Germans.

(Tanganyikan troops with Mk.III Turtle helmets of WWII British use in the early 1960s.)

(The Mk.III Turtle entered service during the second half of WWII. It is Britain’s “forgotten” helmet, overshadowed by the Mk.II Tommy which remained in use throughout all of WWII and long after, and the Mk.IV of the Cold War. Tanzania used the Mk.III in frontline service through the late 1960s and then in reserve.) (photo via militarytour website)

the Zanzibar revolt

The Sultanate Of Zanzibar, a separate entity from Tanganyika, was an anachronism by the 1960s. Conquered by Arabs in the 1600s, it’s original wealth was gained through the slave trade, and later by reexporting goods produced on the mainland. Under the Arab sheikh was a tiny ruling caste, entirely rich sunni Arabs, then a middle caste made up of sunni Arabs, shi’ites of Iranian descent, and people from Britain’s Asian colonies. Finally the huge underclass was black, poor, and with few rights.

(Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah, final sheikh of Zanzibar. As of 2017 he is still alive, in exile in London.)

The final sheikh, Jamshid bin Abdullah, set the country up as a constitutional monarchy with limited legislature. When the British ended ties in 1963, this immediately devolved along racial lines, with the upper classes favoring the Zanzibar Nationalist Party and the black population favoring the Afro-Shirazi Party.

Zanzibar had a tiny security force equipped with leftover WWII British guns. The officers were exclusively Arab while the lower ranks were largely black. The sheikh could already see the handwriting on the wall, and tried to head off trouble by dismissing most of the black policemen and military officers, and replacing them with Arab mercenaries from the Middle East. This backfired as now there was a large number of unemployed and angry men with military training and knowledge of police tactics.

Zanzibar’s full independence lasted only about six weeks. An immigrant Ugandan named John Okello riled up the black population, which didn’t take much considering the discrimination they faced from the sheikh. On 12 January 1964, Okello and 700 other men (many, police dismissed by the sheikh) armed with machetes staged raids on police stations. Arming themselves with the police’s Enfields and Webleys, they then cleaned out the national armories, distributing the guns therein. According to several sources, about eight dozen SKS rifles (not native to Zanzibar’s lineup) seemingly materialized out of thin air.

(A pair of Okello’s goons in 1964 armed with a SMLE and Enfield No.4 Mk.I, both WWII British rifles, seized from the sheikh’s armories.)

(“Field Marshall” John G. Okello after seizing power. The rifles are Enfield No.4 Mk.Is, the machine gun is a Bren, and the helmet is a Mk.III Turtle. All of this was ex-British WWII gear.)

(The pistol in the lower left is a WWII British army Webley Mk.IV, while the one in the center is a Victory revolver, also of WWII.)

(The Smith & Wesson Model 10 “Victory” pistol was based on the M1899 revolver. During WWII, more than half a million were sold to the British, Canadian, Australian, and South African armies. It was a double-action six-shooter chambered in .38/200.)

(The serial number was prefixed by a V, hence the nickname. After WWII, leftover Victory pistols were distributed to second-line and client forces around the British empire.) (photo via freeexistence.org website)

The next few days were marked by racial violence amongst the most disgusting Africa has seen, before or since. An estimated 10,000 people died; mostly of the Arab upper and middle classes. The sheikh fled in his yacht. Okello called himself “Field Marshall” and declared Zanzibar a “People’s Republic”. Aid from the USSR, East Germany, and China quickly arrived.

(Zanzibar was an incredibly dangerous place during the revolution. Here, a car’s passenger has a looted SMLE at the ready.)

(For his first interview with the BBC, Okello tried to present a more statesmanlike demeanor.)

(Tanganyikan troops eventually restored order. These soldiers are armed with H&K assault rifles, but wear Mk.II Tommy helmets of WWII British origin.)

(A Tanganyikan police detachment used SMLEs of WWII vintage to guard the House Of Wonders, the deposed sheikh’s former residence.)

Okello formed a new army, called People’s Freedom Force, armed both with WWII British leftovers and increasingly, post-WWII handouts from the communist world. The PFP was poorly trained and more of a political marching club than fighting force. Even before unification, Tanganyikan police began to take over law enforcement functions.

(People’s Freedom Force recruits drilling with Enfield No.4 Mk.I rifles in 1964.) (photo via Sovfoto)

(The People’s Freedom Force with Cold War-era SKS rifles that replaced the sheikh’s WWII British weapons shortly before Zanzibar and Tanganyika merged into Tanzania.)

Okello was a erratic and arrogant man and grew increasingly weird in his speeches. Zanzibar’s people soured on him, as they did not want to exchange the hated sheikh for rule by a lunatic. After unification, the Tanzanian government disavowed his “Field Marshall” title, quietly eased him out of politics, and eventually kicked him out of the country. Much later, in 1971, Uganda’s dictator Idi Amin became fascinated by Okello’s story and invited him to a personal audience. By then Okello was so delusional that he either didn’t realize or didn’t care that he was meeting Africa’s most paranoid and brutal ruler, and greeted Amin in a casual, flippant manner. During the meeting he told Amin that now Uganda had two field marshalls. He was never seen again.

the unification of Tanzania

(flag of Tanzania)

Throughout early 1964, Zanzibar and Tanganyika drifted closer together. By March, Tanganyikan police and army advisors were effectively running Zanzibar’s institutions, and on 26 April 1964, Zanzibar united with Tanganyika, with the latter absorbing the island’s small, backwards military and it’s equipment. Several months later, the united republic changed it’s name to Tanzania.

the Dar Mutiny

As the 1964 events in Zanzibar were unfolding, Tanganyika itself faced a rebellion by it’s military, known in the Commonwealth as the Dar Mutiny.

This incident’s causes date back to WWII and the King’s African Rifles. Many of Tanganyika’s WWII veterans felt slighted (perhaps, rightfully so) that the British Empire sent them around the world to fight for political rights they themselves did not receive, and by limited career opportunities after the war. After WWII the K.A.R. maintained the colonial restrictions in that overall commands were always European, and black soldiers overall were limited as to how high they could be promoted.

After independence in 1961, the situation was exacerbated as British officers still led the force. As late as the end of 1963, the Tanganyikan army was led by a British general, and below him 29 British officers occupying every slot of importance. This was not due to any ill aims by the UK; there were simply not enough Africans of sufficient experience yet. The British were well aware of the catastrophic collapse of the Congolese military in 1960 when Belgian officers were prematurely kicked out after independence there, and did not want to see the same fate befall their own former colony.

Regardless, two years after the nation became independent, it was considered offensive to still be taking orders from foreigners. This view was shared by many Tanganyikan civilians.

The army also wanted better pay. This view was not necessarily shared by ordinary citizens, who felt the military pay scale was fine as-is. None the less, the army’s concerns went beyond just normal soldier’s gripes. The 1st Battalion’s garrison, Colito Barracks, had not been modernized since WWII and some enlisted infantry were sleeping on “beds” made of wood.

(British troops at Colito Barracks.)

On 19 January 1964, rank & file enlisted soldiers of the 1st Battalion angrily confronted their British officers at Colito Barracks, then went out into the streets of Dar-es-Salaam establishing roadblocks. By the end of the day, almost the entire rest of the battalion had joined them. On the 20th, soldiers began seizing government buildings in Dar-es-Salaam, and the 2nd Battalion in the Tanzanian heartland also staged a similar rebellion. British officers were either confined to their quarters or told to leave the country. By nightfall on the 20th, the situation in Dar-es-Salaam started to deteriorate. Bored and still-angry soldiers started looting shops, and there was no clear answer as to if the army, the civilian government, or anybody, was running the country. The civilian police department was left in a bind, as soldiers were now wearing only partial uniforms or street clothes, and intermingling with looters.

(Taken by a Briton from the safety of a hotel room, this photo shows (on the right) a rebelling soldier armed with a WWII Bren machine gun.)

While the rebelling army had repeatedly said it was not staging a coup, perhaps it now realized it had backed itself into a corner, and began issuing new demands above and beyond the original requests for a 150% pay increase and an end to foreign officers. By Friday 24 January, the fifth day of the rebellion, the situation was deadlocked and Tanganyika’s president, Julius Nyerere, requested British assistance.

(President Nyerere with British soldiers during the rebellion.)

the British intervention

Great Britain’s interest in the rebellion was two-fold. The primary goal was to avoid a repeat of the bloodbath that had happened on Zanzibar earlier that year. In Dar-es-Salaam, there were a sizable number of British citizens, and also ethnic Pakistanis, Sinhalese, and Indians which technically were their now-independent homeland’s responsibility, yet still holders of British passports from the WWII era. Besides guaranteeing their safety, the second objective was to prevent Tanganyika from backsliding into a banana republic as other decolonized African countries had.

The closest large warship was the aircraft carrier HMS Centaur near the Sea of Oman, conducting training en route to a planned deployment to the Orient. HMS Centaur was ordered to proceed to the British base at Aden (today in Yemen) to embark the 45th commando battalion of the Royal Marines, along with RAF helicopters and armored cars of the British army’s Aden garrison.

(HMS Centaur in the 1960s.)

HMS Centaur was the leadship of eight Centaur class “light fleet carriers” ordered during WWII; and the only one actually completed to the original WWII layout. In Royal Navy thinking during WWII, the “light fleet” category would fill an upcoming niche inbetween the older designs and lend-leased escort carriers, and the planned four Audacious class large aircraft carriers. (Of the latter, only HMS Eagle and HMS Ark Royal were ever finished, 7 – 10 years after WWII ended).

Of eight planned 24,000 ton displacement Centaur class ships, none was finished by the end of WWII. Four were cancelled outright. HMS Albion and HMS Bulwark were modified into support carriers years after WWII ended, and HMS Hermes (originally HMS Elephant) was finally completed as an aircraft carrier in 1959 but to a much different design.

HMS Centaur had her keel laid during May 1944 but due to other priorities work proceeded slowly, coming to a crawl with the end of WWII in September 1945. The hull was structurally complete enough to be launched on 22 April 1947 but work again then stopped; as it was debated whether to enlarge the ship making it more suitable for Cold War-era jets, or, to convert it into a helicopter carrier or some other role. Funds for neither idea were granted and the hull sat idle. With only minor modifications from the WWII plans, HMS Centaur was finally able to run builder’s trials in March 1953 and commissioned on 1 September 1953, more than half a decade behind schedule.

HMS Centaur was 738′ long with a 123′ beam, steam-powered with a top speed of 28 kts. This ship was certainly not a design of the Cold War; lacking a modern flight deck and being 100′ shorter than the Essex class the US Navy flew piston-powered Hellcats off of during WWII.

(Taken in Hong Kong several months after HMS Centaur’s African mission, this photo shows how large the postwar Gannets and Sea Vixens were in comparison to the WWII flight deck.)

Due to post-WWII cuts to the Fleet Air Arm, in addition to the increased size of Cold War-era naval warplanes, HMS Centaur had onboard only 24 aircraft in 1964: a dozen Sea Vixen jet fighters, four Gannet early-warning radar planes, and an assortment of helicopters including two of the RAF’s big twin-rotor Belvederes. The ship had to accelerate into a headwind to achieve sufficient airflow to fly the Sea Vixens, and maintenance on the Wessex helicopters and Gannet turboprops was cramped in the hangar deck originally designed for piston-engined fighters during WWII.

(The twin-rotor Belvedere entered service in 1961 and was a useful asset to the WWII-era HMS Centaur in 1964.)

The journey to Dar-es-Salaam was not pleasant. A total of 592 marines, four armored cars, thirteen Land Rovers, and the two Belvedere helicopters were embarked on the carrier. The Royal Marines bunked on the WWII hangar deck with HMS Centaur‘s fighter wing being moved onto the flight deck, meanwhile the RAF crewmen slept topside inside their Belvederes which were too large for the WWII elevators anyways.

(HMS Centaur’s escort in 1964 was HMS Cambrian, a WWII “C”-class destroyer, shown here on u-boat patrol.)

(By the 1960s HMS Cambrian had been upgraded with Cold War-era systems like the Squid ASW launcher. The device on the stern is neither a weapon nor sensor, but rather a ‘gash chute’ which guided rubbish clear of the ship.)

the ammunition fiasco

(HMS Centaur’s honor guard with a visiting dignitary in the 1960s. The carrier’s WWII-vintage Enflields shown here would play a role in the 1964 intervention.) (Imperial War Museum photo)

En route, it was discovered that the small arms ammunition loaded in Aden was .303 British left over from WWII, not 7.62 NATO for the L1A1 rifles used by the Royal Marines. After deliberation, it was decided to pool together the small arms, all WWII Enfields, from the watchstander armories aboard HMS Centaur and HMS Cambrian, and swap with the Royal Marines to ensure adequate ammunition ashore.

The British marines planned on making arms & ammunition captures a high priority; had the situation escalated they would have used any semi- or full-auto Tanganyikan weapons captured, specifically the FN FALs. As these also used 7.62 NATO, intact armory captures would be double-beneficial, as the FALs themselves would be used and their ammo then used to support the L1A1s waiting aboard the ships. Meanwhile any Tanganyikan .303 British rounds captured would be immediately useful in the Enfields brought ashore in the first helicopter wave.

(The February 1964 issue of Life showed a Royal Marine with an Enfield No.4 Mk.I.)

In the end, the worry was for nothing, as there was no resistance. Still before daybreak on Saturday 25 January, HMS Cambrian began firing 4.5″ rounds towards the sea, then joined by the Bofors 40mm AA guns aboard HMS Centaur, to make it appear that a much larger flotilla was offshore bombarding something. The WWII-era guns aboard the ships certainly threw off a noticeable report. The marines were landed by helicopter in the soccer field of Colito Barracks and the surrender of the 1st Battalion came quickly. The 2nd Battalion, in the country’s center, was only half-heartedly participating in the rebellion to begin with and gave up even faster.

(HMS Centaur offshore of Dar-es-Salaam, with the two big Belvederes on deck.)

(HMS Centaur’s Sea Vixens buzzed the city in a show of force.)

outcome

The operation lasted less than 24 hours, and there were no combat casualties. For a week or so after the rebellion ended, farmers around Colito Barracks turned in Enfields to the British; apparently near the end rebellious troops had thrown them into crop fields to avoid being arrested while armed.

(HMS Albion (to the rear, with Belvederes on deck) and HMS Victorious after relieving HMS Centaur.)

HMS Centaur remained offshore only nine days. The Royal Marines were evacuated via contracted flights with BOAC airline. HMS Centaur was relieved by HMS Albion (the second planned Centaur class hull of WWII, which had been converted into a helicopter assault ship after the war) and HMS Victorious (a WWII-veteran Illustrious class fleet carrier enlarged and modernized in a very expensive eight-year postwar upgrade).

disbandment of the Tanganyikan army and formation of the TPDF

President Nyerere disbanded the 1st and 2nd Battalions, leaving the country without a military. For several months, a detachment of the Nigerian army was stationed in the country to provide national defense.

After the country’s unification with Zanzibar, the Tanzanian People’s Defense Force was formed. Any lineage to the old King’s African Rifles was abolished. In contrast to the holdover colonial structure, the TPDF was organized on modern lines as three (four after 1966) combined-arms battalions, later changed to a mixed brigade / battalion structure. The British-style rank system was retained.

The army’s culture was changed, to stress the principle of subservience to the civilian government. Some of the rebellion’s grievances were addressed: pay was increased (but not as much as had been demanded) and the foreign officer program ended. One issue identified was that the “first” Tanganyikan army spent most of it’s time on base, with soldiers grumbling about the barracks. To that end, an increased tempo of field exercises was set. Even if they didn’t accomplish much militarily, they would give troops something to do.

The force’s initial equipment was unchanged; it was all WWII vintage less the FN FALs and H&Ks, and SKSs inherited from Okello’s little ragtag army in Zanzibar.

Julius Nyerere and the east bloc

A socialist, President Nyerere was courted by both the USSR and PRC after the Sino-Soviet split; with both factions of the communist world supplying weapons. Often it was a game of one-upsmanship, with the Chinese supplying rifles, then the Soviets artillery and APCs, then the Chinese tanks, and so on.

(Julius Nyerere and Chou en-Lai, Chairman Mao’s plenipotentiary to ‘socialist Africa’.) (Camerapix photo)

Nyerere’s vision of marxism differed greatly from both Moscow’s and Beijing’s. Major businesses were nationalized and there was a nod towards collective farming, but rural life went on as before and petty capitalism in the cities was encouraged. Tanzania paid lip service to, or ignored altogether, aspects of communism such as “class struggle” and state atheism. Nyerere was hostile towards Rhodesia, South Africa, and especially against Portugal’s colony in Mozambique, but had no ill will against NATO and maintained friendly relations with the USA.

(Nyerere with JFK in the 1960s.)

The USSR both supplied the country directly, and through it’s proxies in the Warsaw Pact – especially Czechoslovakia and East Germany. China supplied directly and also used North Korea as a proxy.

(President Nyerere’s reception during a state visit to Pyongyang. He privately considered Kim Il-sung to be an idiot but North Korea a useful ally.)

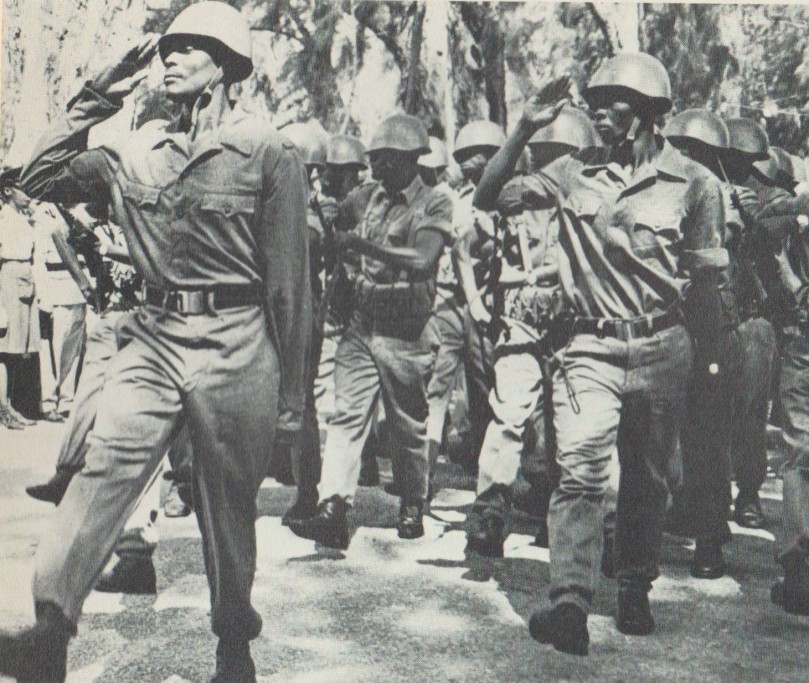

(East German advisors brought the goosestep to Tanzania in the 1960s. The helmets are the Cold War-era SSh-60 of Soviet manufacture, which replaced the WWII-era British helmets.)

The first items to be replaced were the bolt-action Enfields, first by SKSs and then by AK-47s, from both China and the Soviet sphere.

communist-origin WWII weapons in Tanzania

(Soviet PPSh-41 as supplied to Tanzania by China in the 1960s.)

The PPSh-41 submachine gun served the Soviet army well during WWII. It was 2’10” long and weighed 8 lbs empty. It fired the 7.62x25mm Tokarev cartridge (1,601fps muzzle velocity) from a 71-round drum at 900rpm.

(Tanzanian troops with PPSh-41 submachine guns in the late 1960s.)

(Overhead view of the PPSh-41’s drum magazine.)

Although of Soviet origin, most of Tanzania’s PPSh-41s were supplied third-hand by China and North Korea. Both sources also supplied ammunition, as did Czechoslovakia from the opposing camp.

(Chinese-made 7.62 Tokarev cartridge and export box.)

Despite the significant number placed into use, the PPSh-41’s career in Tanzania was not long. In army doctrine, submachine guns were paired with SKS rifles (or the older WWII-era Enfields) in infantry squads and substituted carbines in secondary roles. The widespread introduction of the AK-47 in the late 1960s and thereafter made the distinction redundant and by the mid-1970s the PPSh-41s were out of service.

A small number of WWII-era DP light machine guns were also provided by China. Like the PPSh-41, the USSR had provided the DP to Mao’s communists during the 1945-1949 Chinese civil war and then again during the Korean War. The DP fired the 7.62x54mm(R) cartridge from an overhead 60-round pan at 550rpm.

The DP was very unpopular in Tanzania and few were delivered in the 1960s. It failed to displace the WWII-era Brens from service, and was itself replaced by the RPK later in the decade.

(Tanzanian troops with SG-43s in the late 1960s. The rifleman at the end already has an AK-47.)

The Goryunov SG-43 machine gun was 3’10” long and weighed 91 lbs on it’s wheeled carriage with gunshield. During WWII, this full-auto, belt-fed weapon was common in the Soviet army. It fired the 7.62x54mm(R) cartridge (2,624fps muzzle velocity) at 600rpm.

After WWII, the Soviet army joined the worldwide trend towards the general-purpose machine gun (GPMG) and heavy machine gun categories, and the SG-43 was left without a tactical niche. The SG-43s were doled off around the world. Tanzania began receiving SG-43s in the mid-1960s. Like the 61-K described later, the SG-43s could have come from any or multiple sources, as all of Tanzania’s communist weapons vendors used the gun during the 1960s.

The SG-43 was surprisingly popular in Tanzania. It offered a sustained-fire capability lacking in the Bren, and the cartridge could penetrate thick savanna grasses. These WWII guns remained in Tanzanian use until the end of the 1970s.

China attempted to introduce the Type 53, it’s clone of the WWII Soviet Mosin-Nagant M44. The Tanzanians felt these were not only no improvement, but a step back from their existing WWII Enfields. Further offers were refused and those delivered saw very little use.

(Tanzanian ZiS-2 battery in the late 1960s or early 1970s. The gun teams are armed with PPSh-41s, another WWII weapon.)

A small number of ZiS-2 towed anti-tank guns were delivered to Tanzania sometime in the late 1960s. This WWII Soviet army weapon, overshadowed by the more famous ZiS-3, fired a 57x480mm(R) AP cartridge, the BR-271K. This round’s 7 lbs penetrator had a phenomenal 3,282fps muzzle velocity and before 1942, could defeat pretty much any tank in the world. The Tanzanians also liked them because they were light (1¼ tons) and could be pulled by Toyota 4x4s. There was also a general-purpose HE round, the O-271, that enabled them to be used as light field guns out to 5 miles.

While the original maker was obviously the USSR during WWII, how these ended up in Tanzania, and how many were delivered, is not clear. This was not a common WWII weapon, only 10,016 having been made, and none of Tanzania’s known weapons suppliers list them on any delivery manifests. North Korea (a known ZiS-2 operator) might have been the source, as that country isn’t exactly forthcoming with honesty as to weapons deals. Another possibility is that they were delivered by the Soviet Union as part of a 1964 armored car sale and considered “included equipment”. Still another possibility is that the delivery was brokered through East Germany to avoid a paper trail to the USSR, and that the records were destroyed prior to German reunification in 1990.

In any case, these guns were Tanzania’s first artillery assets, but apparently did not remain in use very long. None were observed during the 1978-1979 war against Uganda.

(WWII Soviet 61-K anti-aircraft gun on parade in Tanzania in the early 1970s.)

The 61-K was a standard Soviet army 37mm anti-aircraft gun of WWII, and one of the most-produced weapons in it’s role of any nation during the war. This semi-automatic gun fired the OR-167 round, a 37×252(SR)-T cartridge with 2,887fps muzzle velocity, out of a 5-round clip magazine at 45 to 60rpm (the rate of fire being limited by the need to constantly change clips). The whole set-up (gun and ZU-7 carriage with 40 clips aboard) weighed 2¼ tons and could be towed at 31mph on paved roads. The gun’s elevation was -5° / +85° and traverse was a full 360°, both being manual via handwheels.

It’s quite likely Tanzania received these guns, and their ammunition, from multiple sources. Every single one of the country’s east bloc arms vendors used the 61-K after WWII. Additionally China produced an exact clone called the Norinco Type 55 to join Soviet-made guns imported before the USSR-PRC rift; while China, North Korea, and Poland manufactured spare parts; and China, North Korea, Czechoslovakia, and Poland made ammunition in addition to commercially-sold ammunition marketed by Yugoslavia, Egypt, and Pakistan onto the African market. The 61-K was first observed in Tanzanian service during the mid-1960s.

During WWII, the Soviets estimated that 0.11% of rounds fired had been hits (the OR-167 ammunition did not have a VT fuze and thus needed to directly strike the plane). This was not bad for a manually-operated, visually-aimed gun and was comparable to WWII German and Japanese AA weapons of similar caliber. None the less, by the 1960s and 1970s, the 61-K would have been hard-pressed to engage a modern jet and was by then more of a low-altitude asset against helicopters.

The 61-K was Tanzania’s first AA weapon of any type and remained in use into the 1980s. Whatever it’s limitations by then, it was simple to use and durable.

The Soviets delivered some 82-BM-37 (and related 82-BM-41) infantry mortars, of WWII vintage, to Tanzania in 1971. Both fired a 82mm 6½ lbs round out to roughly 3,300 yards. Besides any ammunition provided by the USSR, China also manufactured rounds for this mortar during the Cold War.

Also in 1971, the Soviets delivered fifty PM-43 heavy mortars to Tanzania. This weapon entered service during the middle of WWII. This 120mm mortar had a range of 6,200 yards. In Tanzanian service, the PM-43 is a bit mysterious as the delivery was known to have taken place, but it was never listed on any TPDF equipment tables.

the 1978-1979 Kagera war

Fought against Idi Amin’s Uganda, this was Tanzania’s only international conflict.

The start of this conflict, which ended in disaster for Uganda, was a spur-of-the-moment decision by Amin. Following a failed coup after which some of the plotters fled to Tanzania, Amin flew into a rage and ordered immediate plans to invade that country.

On paper, Uganda’s military in 1978 was superior to Tanzania’s. It was typical for an African military of the late 1970s, with it’s gear running from grotesquely obsolete to cutting-edge.

(Just like Tanzania, Uganda had acquired some WWII-vintage DP machine guns over the years. Here, Idi Amin is inspecting one.)

(Tanzanian troops walk past a wrecked Ugandan MiG-21 “Fishbed” fighter after overrunning it’s airfield in 1979. The modern, supersonic MiG-21 was used by both sides during the war. Whatever the Tanzanians didn’t shoot down was destroyed on the ground.)

(Tanzania’s military did not use any ex-RAF Dakotas when it became independent in the 1960s, but Uganda’s did. At least two of these WWII transports were still in use during the Kagera war.)

(The Cold War-era, Soviet-made T-54/55 was the most modern tank Uganda had, with only a half-dozen or so in inventory. Tanzania used the T-59A (a T-54/55 copy), in addition to the Chinese-made Type 62.)

(Uganda’s best vehicle of the war was the modern Czechoslovak-made OT-64 Skot APC.)

Idi Amin himself was a veteran of the King’s African Rifles, having enlisted in 1946. (He later ordered his record falsified to indicate that he was a WWII veteran.) As a young man, he was tremendously athletic, nothing like the bloated caricature of the 1970s. Amin was part of the K.A.R. 21st Battalion in Kenya, and fought in the Mau-Mau uprising. Some of his then-comrades in the 21st Battalion were later senior officers in the Tanzanian army during the 1978-1979 war. Amin rose from private to corporal to sergeant, and finally afende; a senior NCO position and the highest rank a black soldier could hold. After Uganda became independent in 1962, Amin’s rank was changed to commissioned lieutenant. He was promoted to major and then in 1970, made a general.

(Idi Amin congratulates a crewman of one of Uganda’s Israeli-supplied M4A1 Shermans.)

Uganda had been an ally of Israel and in 1969, that country sold Uganda twelve upgraded M4A1 Sherman tanks. These WWII tanks were Uganda’s first. Upon seizing power on 25 January 1971, Amin stated that he intended to maintain the alliance with Israel and other equipment followed, including jeeps, recoilless rifles, radios, and training for Uganda’s MiG fighter pilots. The flight training was superb and in the mid-1970s, Ugandan fighter pilots were considered the best in equatorial Africa.

Uganda’s foreign relations deteriorated under Amin. In 1972 he ended relations with the UK, up until then the country’s main defense supplier. The relationship with Israel collapsed. During the mid-1970s, the ill-tempered Amin improbably offered his services to mediate both the Northern Ireland dispute and Arab-Israeli conflict. Not surprisingly, nobody took him up.

Amin gradually turned against Israel and in 1972 ended all military cooperation with that country. A second planned batch of upgraded Shermans was cancelled. After the 4 July 1976 Israeli commando raid that freed hostages at Uganda’s Entebbe airport, Amin openly called for Israel’s destruction.

As Uganda is landlocked, Amin’s behavior caused problems not only with acquiring arms abroad but also, physically obtaining them. A spat with Kenya closed off Mombasa as a delivery port, and after the war against Tanzania started, obviously nothing would be coming through Dar-es-Salaam. Uganda’s options were limited to a rail link with Zaire, which required weapons to completely cross Africa from the Atlantic side, or slow piecemeal air cargo deliveries.

(Ugandan T-34 in 1978-1979.)

By 1978, Amin had alienated pretty much the whole world and Uganda’s only ally was Muammar Quadaffi’s Libya. That country gave Uganda ten WWII-vintage T-34 tanks, rounding out it’s armored force. Tanzania had more modern tanks than Uganda’s mix of WWII types and modern designs put together. Amin’s diplomatic chaos left the Ugandan army with a mish-mash of European, American, and Soviet rifles, radios, and artillery; all spanning three decades and much of it incompatible with each other.

On 10 October 1978, without a declaration of war, Ugandan artillery opened up across the Tanzanian border while MiG-17s and MiG-21s bombed the nearest Tanzanian army base, at Bukoba near Lake Victoria. Several hours later, Uganda’s elderly T-34s and M4A1 Shermans, backed up by motorized infantry, crossed the border.

(Ugandan T-34 at the start of the Kagera war. These WWII tanks fared poorly.)

Amin’s vague goal (the whole invasion was planned in under a week) was to overrun some or all of Tanzania’s Kagera province, seek a cease-fire, and then allow the front lines to become Uganda’s new southern border.

(Kagera province.)

(Taken from a Tanzanian news broadcast of the war, the red shows the deepest Ugandan occupation zone. Idi Amin originally planned to halt on an east-west line running from the Rwanda-Burundi border to Lake Victoria; obviously his troops fell far short of that.)

After overcoming stiff resistance from Tanzanian border troopers, the Ugandan advance went quite well for about a week. Ten days in, Ugandan troops had captured the strategic town of Kyaka and cut the Tanzanian highway B8, the main east-west road across the province.

After this however, the invasion began to stall. Only about 20 ½ miles deep into the country, the Ugandan occupation zone was now spread out about 30 miles both on the left and right of the main logistics route, and the advance sputtered. Between the 27th to 30th of October, several attempts to establish a southern bridgehead over the Kagera river failed, and by 31 October the advance halted altogether.

Kyaka Bridge carries Tanzania’s T4 highway across the Kagera river. Having failed to establish a secure bridgehead on the southern bank, it became the de facto limit of Uganda’s occupation zone. After it was decided that the offensive would not be restarted, Amin considered the river to be Uganda’s new southern border and ordered the bridge destroyed to protect his army’s gains. Attempts to bomb it from the air failed miserably while Ugandan troops on the ground apparently feared sniper fire from the southern riverbank. Finally, civilians from Uganda’s Kilembe Mines dynamited the center span.

(Kyaka Bridge after it’s destruction.)

(Idi Amin used some of Uganda’s dwindling foreign currency reserves to contract Spink & Son of London to mint a victory medal even as fighting was still in progress. The medal shows the Kagera river, which Amin intended to be the new border.)

Tanzania’s mobilization and WWII arms in 1978-1979

When the Ugandans struck in late October, the TPDF was divided into four battalions; two of which (more than half the whole military) were around Dar-es-Salaam; a third in the country’s heartland, and the fourth near the Mozambique border. Kagera province was only defended by the border troops and a detached unit of the 202nd Infantry Brigade, headquartered far to the south.

(Tanzania’s railroad lines left over from WWII and the colonial era were invaluable in moving forces towards Kagera province in 1978.)

Throughout October, Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere sought some sort of diplomatic solution. That failing, on 2 November 1978 Tanzania declared war on Uganda. Already a massive national mobilization had started. This was surprisingly well planned out ahead of time. The first wave were ready-reservists from the TPDF, and specially cross-trained units formed out of prison wardens and police officers. The second wave was local ad hoc militias formed in the Lake Victoria region. The final and largest wave was new recruits. The amount of training time needed at each level varied in staggered levels, so a constant and growing pool of reinforcements joined existing TPDF units being redeployed to Kagera province. By the end of November the TPDF had grown from 39,900 men to 100,000.

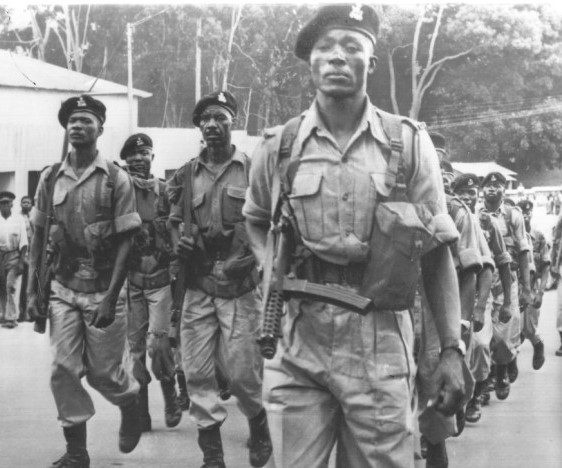

(Callups of the mobilization march in formation during 1979. They are armed with AK-47s but one in the second row has a WWII-era Mk.II Tommy helmet.)

(One of the old SG-43s being readied for service. It’s porter is carrying an Enfield No.4 Mk.I.)

(A callup receives training on one of the WWII-vintage 61-K anti-aircraft guns in 1978.)

The front-echelon troops were equipped entirely with modern weapons, mostly AK-47s (with some FN FALs and SKSs still in use), Cold War-era Soviet artillery, and the modern Chinese tanks. Enough AK-47s and SKSs were available that the second tier forces also had them. A small number of Enfields were reissued; it is unknown if any saw use. The SG-43 was also reissued for combat, as were the WWII-era mortars and AA guns. The ZiS-2, PPSh, and Webley were not seen and probably completely out of use already.

course of the war and outcome

On 25 November 1978, the TPDF announced that it had stabilized the front in Kagera province. Meanwhile Uganda’s last remaining ally; Libya; dispatched 3,000 troops, a Tu-22 “Blinder” supersonic bomber, a T-54/55 tank detachment, and replacement MiGs for Uganda’s air force.

(Libyan Tu-22 “Blinder”)

On 4 December 1978, the TPDF launched operation “Chakaza”, it’s initial counteroffensive. It was commanded by Gen. David Msuguri; who decades before had been Idi Amin’s commander in the K.A.R. In two and a half weeks, the “Chakaza” operation pushed the Ugandans back.

(General David Msuguri)

After the initial successes, Idi Amin ordered the many of frontline units back to their barracks and replaced them with green recruits; mostly poor villagers drawn from the West Nile region along the Sudanese border. These illiterate tribesmen were given almost no modern training and completely unprepared for what was about to come.

(The most immediate obstacle to the operation “Chakaza” counteroffensive was crossing the Kagera river. Tanzanian sappers (combat engineers) laid a British WWII ‘bailey bridge’ over the Kyaka Bridge which the Ugandans had dynamited.)

(Tanzanian VIPs cross the WWII ‘bailey bridge’ later during the Kagera war.)

(The church on the southern side of the bridge was destroyed by Ugandan artillery in 1978 (as seen in the previous photo) and never rebuilt. The disused guard shack on the highway also probably dates to the 1978-1979 war.)

(After the Kagera war ended, the ‘bailey bridge’ was disassembled so a replacement of the Kyaka Bridge could be built. Part of it was preserved as a war memento.)

On 24 December 1978, Amin ordered a general retreat out of what remained of the occupation zone. On 1 January 1979, Tanzanian troops were back on the prewar border. The country was now at a crossroads. The mobilization was costing Tanzania $1 million per day, plus any ammunition or fuel expenditures. At a two-day conference, Tanzanian intelligence informed Nyerere that the status quo would likely result in a stalemate lasting 2-3 years.

The role of Tanzania’s and Uganda’s intelligence services has almost been completely ignored in accounts of the war. In a hypothetical pyramid of worldwide agencies, starting with the CIA and KGB, the units of the two African countries were towards the bottom but none the less, played a worldwide cat-&-mouse game for several months, with each seeking to acquire black market weapons and block the other from doing so. An example was Spain (in the midst of it’s 1976-1981 transition to democracy), where Ugandan agents attempted to buy rifle ammunition and napalm bombs but were followed and harried by Tanzanian agents which convinced the Spaniards not to sell. Likewise Tanzanians in East Berlin persuaded the East Germans that Amin was already a lost cause. Tanzania meanwhile acquired black market SA-7 “Grail” surface-to-air missiles from an unknown party, probably Yugoslavia or Egypt, which shot down at least two Ugandan MiG-21s.

At the end of the two-day conference, the decision was made to carry the war into Uganda, with a primary objective being the destruction of the Ugandan army and a secondary goal being to weaken Amin politically.

On 20 January 1979, a massive Tanzanian force, at least 10,000 foot infantry along with mechanized infantry, armored units with modern Type 62s and T-59A tanks, AA units, and logistics units; crossed the border. There were two main axis-of-attacks: In the west, one lone brigade sought to capture Mbarara (about 30 miles north of the border). This would cut Uganda’s transportation links to Zaire and also block any outflanking attempt. The east axis, the main one, was equivalent to an American division in size and would capture the city of Masaka (about 35 miles north of the border) then proceed up Uganda’s BLN highway towards the capital Kampala.

The main east axis initially suffered a defeat near Rakai, 16 miles deep into Uganda, but quickly regrouped and resumed the offensive. From then on, the advance was relentless and the steady Ugandan retreat turned into a disorganized panic.

(One of the WWII-vintage 82-BM-37 mortars in action in 1979.)

In the third week of February 1979, the Tanzanian east axis overran both the city of Masaka (it’s initial objective) and the Ugandan army’s Kasijagirwa Barracks. Both were essentially flattened by heavy fighting. Meanwhile the smaller west axis’s lone brigade had long since accomplished it’s objective and was now freewheeling northwards in Uganda’s Great Lakes region.

Far away in Libya, Muammar Quadaffi threatened to declare war on Tanzania and carpet bomb Dar-es-Salaam unless President Nyerere withdrew his troops from Uganda. Civilians calling in to Dar-es-Salaam radio stations ridiculed Quadaffi’s threat and sensing a political advantage, the Tanzanian government stated that not only was it not halting the war, it would now seek combat with any Libyan forces in Uganda. Quadaffi never followed through on his threat.

(A modern Tanzanian Type 62 advances in Uganda. Tanzanian tank crews were highly trained and their officers skilled in armor tactics. Uganda’s hodge-podge of WWII tanks and few T-54/55s simply had no answer to this. The M4A1 Shermans had been in the field for a quarter of a year and many broke down during the fighting. The T-34s were ripped to shreds by Tanzania’s tanks.)

From 10-12 March 1979, a large battle was fought in swamps near Lukaya, a Ugandan city on the equator, 65 miles south of Kampala. A dozen T-54/55 tanks (mostly of the Libyan contingent) and three of Amin’s elderly M4A1 Shermans were destroyed by Tanzanian armor.

This was the last set-piece battle of the war. Less the Ugandan airborne battalion, fighting now as ground infantry, almost all of Amin’s forces broke discipline and began to disintegrate. During the third week of March 1979, the Ugandans failed to dynamite bridges over the Katonga river and Tanzanian forces poured over northwards.

(Tanzanian infantry cross Owen Falls Dam, one of the sources of the Nile river, in April 1979. This force also captured the Ugandan army barracks at Jinja.) (Associated Press photo)

On 29 March, a Libyan Tu-22 “Blinder” supersonic bomber tried to bomb the Tanzanian army’s fuel depot, failing miserably. On 1 April, Tanzanian MiGs retaliated by bombing Entebbe IAP in Uganda, that country’s last remaining inlet for ammunition and spare parts. A Libyan C-130 Hercules was destroyed on the runway. Meanwhile the Tanzanian government expanded it’s goals reflecting it’s army’s successes, and now sought to completely occupy Uganda to permanently eject Amin from power.

(Wreckage of the destroyed C-130 Hercules.)

On 9 April 1979, Tanzanian forces overran Entebbe international airport, which is actually on a peninsula into Lake Victoria about 19 miles from downtown Kampala. The Tanzanians destroyed whatever remained of Uganda’s air force on the ground, and were also surprised to find that Idi Amin had not bothered to repair damage the Israeli commandos had inflicted in 1976.

(A Boeing 707 of Uganda Airlines sits abandoned at Entebbe after the Tanzanians captured the airport.)

On the 9th and 10th, Tanzanian forces encircled Kampala on three sides, with Lake Victoria forming the fourth. A corridor was intentionally left open; the Tanzanian generals wagered that instead of bringing reinforcements in, Ugandan soldiers in the city would try to flee (many did) eliminating the need for bloody urban fighting. None the less, the remaining Ugandans fought bravely from 10-11 April 1979, ending with the capital’s surender. Also on 11 April, advance elements of both the east and west axis units met near Uganda’s northern border with Sudan, having bisected the whole country.

On the morning of 10 April, with Tanzanian artillery already audible, Idi Amin was still inside besieged Kampala, at his estate in the eastern Luzira suburb near Lake Victoria. As it became clear that the city would fall within a day or less, the last flightworthy helicopter in Uganda retrieved him at 16:00 local. A warden at Luzira Prison watched the operation and later told the Tanzanians that they had missed capturing Amin by only eight hours. The helicopter flew 130 miles to Arua, a town in Uganda’s West Nile region where Amin’s support was once strongest.

Fighting on all fronts ended on 11 April. On 12 April 1979, Amin addressed a small band of soldiers at a WWII-vintage dirt airstrip near Arua. He handed control of his government to the most senior personnel present (a Lt Colonel and a Sergeant) and told them he was going to Libya to organize a massive reinforcement force. Instead, a waiting C-130 Hercules flew him to a comfortable exile in Saudi Arabia. The war was over.

final fate of Tanzania’s WWII weapons

Tanzania captured huge numbers of modern arms from the Ugandans in 1979 and actually finished the war with net gains in rifles, machine guns, artillery, and AA guns. Additionally, another tranche of modern weapons from China had been signed in 1978 before the war happened, and was still due to be delivered later in 1979.

(The Ugandans tried to compensate for their lack of tanks by pairing M38 jeeps and recoilless rifles – both provided by Israel in happier times. This vehicle was captured intact by Tanzania.)

(Tanzanian troops move a Soviet-made ZPU-2 AA gun captured intact near Jinja, Uganda in 1979. Tanzania captured so much equipment that some was later returned to Uganda to rebuild it’s army after the war.)

Therefore the remaining WWII-era guns were flushed out of inventory. The Enfields and few remaining Brens were the first to go, to eliminate .303 British from the ammunition stream, followed by the SG-43s and and other old weapons. Some WWII-era mortars and AA guns were kept in lay-up through the 1990s.

Tanzania sought no border adjustments or any other sort of punishment for Uganda starting the war. The occupation was very brief. By late April 1979 a new Ugandan government had been set up and by the end of June, the last Tanzanian forces had left the country.

By the turn of the millennium, all WWII-era gear was out of Tanzania’s active inventory.

(During a January 2014 ceremony, a drill team of the TPDF paraded in K.A.R.-era uniforms including Enfield rifles.)

Reblogged this on Brittius.

LikeLike

Fascinating history and nice details on military obscurities. Also a very interesting look at the politics of the region.

LikeLike

the Sultan of Zanzibar probaby was a ibadi Muslim not a sunni .

Ibadi sect is the third scet of Islam is mainly practices in Oman and a few villages in North Africa

also I would like to ask are you ever planning to do the article on the Enigma machine because I remember reading somewhere that Britain gave some of its former colonies Enigma machine. I hope you do article on that it would be awesome and keep up the good work. Your website is one my favourite website

I only wish you could update it more regularly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

great post, keep on researching and writing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A detailed and fascinating history of the Tanzanian armed forces and the conduct of the Kagera War. Was the Kagera war the last time that WW2-era tanks saw combat action?

LikeLike

The M4 Sherman was used in Lebanon during the 1980s and Iran used some against Iraq in the same timeframe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I believe the K.A.R. soldiers performing bayonet drill during WWII (7th picture from the top) are using Enfield Mk IV’s, not SMLE’s. Fascinating article by the way, I vaguely remember the Tanzanian-Ugandan war and its happy outcome but never knew the details until now. Great reading (as all of the articles on this site)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for writing a good history of this conflict. Especially the brief notes on the intelligence side of things, it’s something that is all too often neglected.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been captivated by your blog ever since I found it, excellent stuff! The photo of the Garret at beginning got me thinking, and you probably know about some of them, but there were many locomotives were manufactured specifically for the war efforts, most famous being the German Kriegslok (one or two of which are still in intermittent commercial service in Bosnia!!) And then there’s the variety of America engines built for the USATC, standard gauge 2-8-0’s and 0-6-0t’s (for service I. Europe), 2-10-0’s in Russian broad gauge (5’) and 2-8-2’s for Indian broad gauge (5’ 6”? I think) in addition to the MacArthur 2-8-2s in 3’ 6”, meter, and 3ft gauges. The brits also built some 2-8-0’s for the WD, one turned up in Iraq not too long ago.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Outstanding. Really fascinating post (came by this via Twitter). Great slice of military history.

One thing jars – the possessive pronoun ‘its’ is spelt without an apostrophe (it’s = it is in abbreviated form).

LikeLike