The defense industry is a business like any other, and just like any other industry, advertising is a part of it. After WWII’s end in 1945, many wartime weapons systems remained in Cold War use and required upkeep, upgrading, resale, integration with newer systems, and eventually disposal.

Some of these advertisements ran in general-interest magazines and newspapers. Others were limited to niche defense journals and trade gazettes, and were typically unseen by the mass public.

Above is a 1971 newspaper ad for the disposal of USS Hazard (MSF-240), an Admirable class minesweeper of the WWII US Navy. Typically, smaller mothballed WWII ships like this were bought cheaply in lots by brokers, then parceled out individually to scrapyards for a profit. USS Hazard was bought by a group of Nebraska businessmen and is today a museum ship in Omaha, NE.

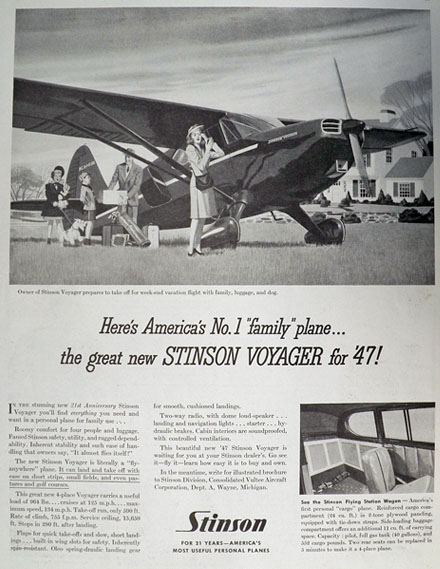

STINSON (1947)

The Stinson Voyager was the post-WWII civilian version of the US Army’s L-9 artillery spotting plane, of which twenty had been used during WWII, along with small batches provided to the Brazilian and Canadian armies. The L-9 was the less-famous brother of the L-5 Sentinel, widely used during WWII and after.

Like many aerospace companies, Stinson sought as much as possible to retain WWII-made production jigs, die molds, and even manufactured parts for postwar civilian sales.

Over a thousand Voyagers were sold after WWII, and some are still flying today. For Stinson’s military line, the L-9 was followed by the successful L-13 Grasshopper of the Korean War. The Stinson name did not live long beyond that conflict. In 1950 it was acquired by Piper and as Voyager sales dwindled the trademark was retired.

ELCO (1947)

Just like Stinson in the aircraft world, watercraft companies – including the Electric Launch Company, or Elco – sought to convert WWII manufacturing assets into postwar civilian sale. During WWII, Elco (a subsidiary of Electric Boat Company in Groton, CT; the USA’s premiere submarine builder) had manufactured wooden-hull PT boats, starting with PT-9, and was the main competitor of the more famous Higgins operation.

The ad above ran in general-interest civilian magazines in 1947. Hoping to capture the market of demobilized GIs, Elco stressed that it’s lineup of pleasure craft were direct descendants of the famous PT boats of WWII. This wasn’t hyperbole as Elco did, as much as possible, incorporate WWII production equipment and even military components into these boats.

Tactically, PT boats no longer had any niche in the Cold War US Navy. Over a hundred were scuttled in the Pacific after WWII to spare the expense of transporting them back to the USA. Financially, WWII killed Elco. The company had tripled it’s production capacity between 1941-1945. With the end of WWII in 1945, it was stuck with idled assets it would never again need, but, now had to pay property taxes on. Sales of pleasure craft were below expectations, while military contracts to the rapidly-shrinking US Navy were nonexistent. By 1948, Elco had fallen below it’s pre-WWII size. In April 1949, Electric Boat Company – now fully absorbed with submarines – decided the Elco division was a dead end. Elco’s New Jersey yard closed for good on 31 December 1949.

BARR & STROUD LTD (1947)

The above ad for naval rangefinders ran only in specialized defense publications in 1947, which is understandable as such equipment was obviously not for sale to the public, nor did it have any real civilian relevance. The advertiser was Barr & Stroud Ltd., a supplier of equipment to the Royal Navy since the 1800s.

(Mk.III rangefinder aboard HMS Revenge during WWII. This battleship was quickly scrapped after the war.)

The optical equipment being advertised, stereoscopic rangefinders and parallax heightfinders, were dying technologies by the time the ad ran. WWII had clearly shown the advantage of radar in the gunnery role, and the rise of jets meant that it was almost necessary for anti-aircraft targeting. Around the world during the late 1940s and early 1950s, WWII-veteran warships were being refitted with radar, those that already had it were being upgraded to newer radars, and no destroyers, cruisers, or frigates designed after WWII lacked it. Nobody was interested in new fire control systems based on optical rangefinding, and precious postwar defense budget money was not going to be used on upgrading wartime optics of this sort.

Barr & Stroud made an unsuccessful attempt to transition to electronics in the early 1950s. Afterwards the company mainly concentrated on smaller shipboard optical equipment and submarine periscopes. In 1977, Pilkington bought Barr & Stroud and retained it as a subsidiary until 2000 when it was sold to Thales. In 2001, Thales dissolved the unit and sold the trademark only to an importer of civilian binoculars. The company known as Barr & Stroud today has no connection to the WWII firm.

US / CANADIAN SURPLUS DISPOSAL (1948)

Two or three years after the end of WWII, with demobilizations completed, the armies on both sides of the planet’s longest undefended border began flushing out obsolete wartime firearms. The ad above ran in Toronto newspapers in 1948. It advertises the Cooey Model 82 rifle. This single-shot bolt-action weapon was a Canadian emergency program for training rifles during WWII. Model 82s were used by the Royal Canadian Air Force for boot camp training. A very inexpensive .22 rifle, the Model 82 was none the less well-built and did it’s job. With the end of the war, it was no longer needed and made available to civilian distributors, mainly in Quebec and Ontario. The quality of those sold, like M1903s in the USA’s CMP effort, varied. Some were beat-up, most were in very good shape, some were unused and still had factory grease.

Cooey Model 82s found their way all over Canada in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and some migrated south of the border to Michigan, New York, and Minnesota. Their simplistic design hid a very rugged construction and they held up well over the decades. They shot .22LR and .22 Short cartridges equally well, and were pleasurable and accurate recreational rifles. As they are rimfire and have a magazine capacity of 0, modern Canadian firearms law places them in the “Non-Restricted Category”, the most lenient in 21st century Canada, meanwhile in the USA they are wholly unregulated.

South of the border, the US Army had two big tranches of WWII surplus flushes, the first in late 1945 and a much larger one in 1948. The above ads show one of the favorite pieces of WWII surplus amongst the public, the Willys jeep.

INTERNATIONAL PAINTS LTD (1948)

All of the victorious Allied navies shrunk in size after WWII, but none more so than the Royal Navy. The undisputed largest navy on Earth in 1939, by 1949 it had been surpassed by the American and Soviet navies and was only marginally stronger than the rebuilding French fleet. Without question, many of the surviving WWII warships Britain still operated in the late 1940s would never have 1-for-1 replacements funded, so it was imperative that these ships be kept operational for as long as possible.

The above advertisement from International Paints Ltd. ran in naval and shipbuilding periodicals in 1948. It showcases the company’s line-up of specialized maritime paints and non-skid toppings, specifically Tanctectol which was applied to areas of warship interiors exposed to fuel or harsh chemicals.

The warship pictured is HMS Vanguard, Great Britain’s final battleship, which began construction in 1941. Throughout WWII, work started and stopped periodically as the Royal Navy more urgently needed first convoy escorts, then aircraft carriers, then later still amphibious ships. The battleship was finally finished in 1945 after Japan’s surrender and commissioned in May 1946.

In some ways, HMS Vanguard was a paradox. As the advertisement states, this was the best British battleship design with a superior armor layout and faster engines than any Royal Navy capital ship since the lost battlecruiser HMS Hood. HMS Vanguard was the only British battleship designed with radar from the outset and the only one that landed helicopters. On the other hand, the design had some old features shoehorned in, to simply get the vessel finished as fast and inexpensively as possible. The eight main Mk.I 14″ guns were leftover unused spares from the now-vanished Revenge, Renown, and Hood classes.

Even as the white ensign was raised on HMS Vanguard in 1946, there was a bittersweet understanding in the Royal Navy that there would never be another British battleship and the clock was ticking for HMS Vanguard herself. Obviously all care was taken to preserve the battleship during her operational career, which in the end only lasted nine years followed by a stint in reserve.

International Paints Ltd. is today known as International Paint and is still headquartered in London, and still uses the four-bladed propeller logo as in the 1948 ad. The trademark for Tanctectol was allowed to lapse in 1992 so presumably it is no longer in the company’s line-up.

WESTERN ELECTRIC (1953)

For defense contractors in the early Cold War era, one key to getting military orders was integrating new systems with existing WWII-era weapons. The 1953 advertisement from Western Electric above is a good example of this marketing strategy. It was for the M33, a new trailer-mounted radar fire control system for anti-aircraft units.

The ad illustrates how the M33 would coordinate the fire of heavy AA guns. In a nod to Wall Street, it also describes how the company’s military research directly benefited it’s main profit endeavor, the USA’s telephone system aka “Ma Bell”.

Above are the two WWII-legacy systems shown in the ad; the M1 anti-aircraft gun and the Ford GPW jeep. Also WWII-legacy, of course, are the soldier’s M1 Garand rifle and M1 pot helmet. All were very much still in US Army use in the 1950s.

As it turned out, the era of towed, hand-loaded AA guns which had dominated WWII, such as the USA’s 120mm M1 or the German 88mm FlaK 37, was over. As the M33 entered service, it was mostly used with the MIM-3 Nike, the US Army’s first operational surface-to-air missile.

Western Electric remained a strong company through much of the 20th century. In 1986, it was bought out by AT&T which retained the trademark. In 1996, AT&T spun off this division as Lucent Technologies, bringing an end to Western Electric’s 127-year history.

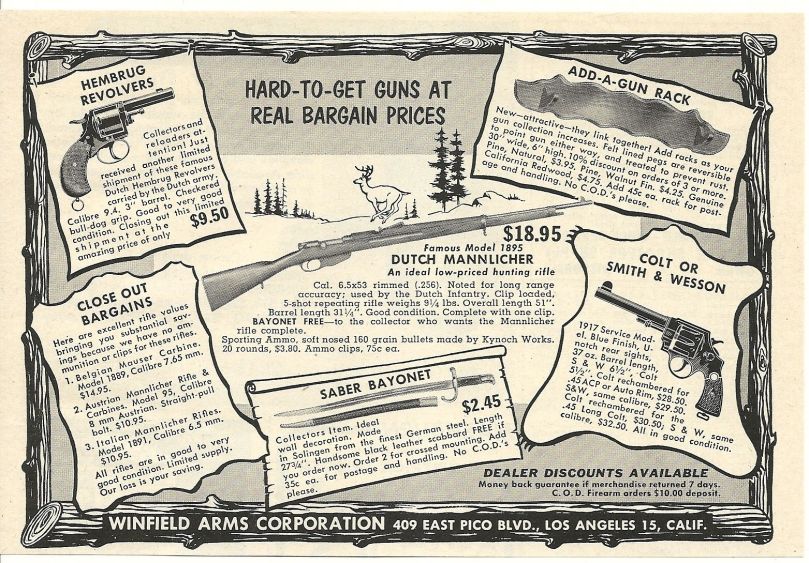

WESTERN ARMS CORPORATION / WINFIELD ARMS (1950s)

The advertisement above is from Western Arms and ran in civilian magazines during the early 1950s. The WWII handgun pictured, described as a “W.A.C. Model A”, is actually a MAB II Mle.A, a pre-war French design firing the .25ACP cartridge. During the occupation, Germany made about 1,100 of these guns which they considered unimpressive. MAB resumed French production in 1945 and these guns were distributed to police around France and it’s crumbling overseas empire. The “W.A.C.” designation was simply new grips with the Western Arms Corporation logo in place of MAC’s.

Ads like this one, from small distributors like this for cheap guns like this, were common on the pages of Shotgun News, Field & Stream, American Rifleman, etc in the late 1940s and the 1950s. What makes it interesting is the backstory of Western Arms and it’s offshoot Winfield Arms. It is one few people today (and certainly none of Western or Winfield’s customers at the time) know about.

There was a brief period where the USA had no centralized national intelligence service. The Office of Strategic Services disbanded shortly after Japan’s September 1945 surrender, and the Central Intelligence Agency was not started until September 1947. In the 2-year interim, intelligence needs were met by the US Army’s and US Navy’s own internal services, and an office of the State Department.

During WWII the OSS ran some covert weapons projects, the most famous being the FP-45 Liberator. Originally a US Army idea, the Liberator was an ultra-crude, dirt-cheap ($2), smoothbore .45ACP gun. A million were ordered. The plan was to drop them en masse into occupied countries as an inexhaustible way for civilians there to kill an Axis soldier and secure his weapon for more efficient resistance use.

The US Army lost interest in the Liberator. Generals MacArthur, Stilwell, and Eisenhower all questioned if means to deliver weapons behind enemy lines existed, why not deliver something better. In the Pacific, friction came from the British and Free French. The reality was that once their Japanese-occupied colonies were liberated, they did not want “the natives” with means of resisting European rule.

The US Army transferred the Liberator to the OSS which was very enthusiastic but lacked means to distribute the guns. In the end, 100,000 went to Chang Kai-Shek’s China, never to be heard about again. Several thousand were sent into occupied France, accomplishing little. Small batches were dropped onto the Greek island of Crete and the Philippines. The plan was a flop. After the war, the remaining unused stockpile in Europe was largely dumped into the English Channel, while most warehoused in the USA were scrapped.

True to their fears, the French recovered a Liberator being used against them by Ho Chi Minh’s fighters in Indochina during 1946.

During the 1945-1947, the State Department conceived an idea for basically doing the Liberator project in reverse. Instead of distributing American guns to allied fighters abroad, American operatives would be distributed abroad to collect firearms. Millions of WWII guns were floating around Europe and Asia, and bringing them to the USA would hopefully choke off armed instability in the wake of WWII’s chaotic conclusion. When the CIA was formed in 1947, it liked the idea, and further saw it as a “black procurement” opportunity to obtain weapon types untraceable back to the USA, to support anti-communist forces abroad.

Western Arms Corporation was formed in California during 1947. It’s involvement with the CIA started in 1950, when it was in dire straits and bailed out by an investor named Leo Lippe, in turn aided by a “field buyer” named Sam Cummings. Starting in 1951, Western Arms began importing guns into the USA under the plan. To say that Western was a “CIA front company” is untrue, it was a genuine enterprise which did legitimate business on it’s own. On the other hand, it was obviously no average mom& pop store.

Winfield Arms Corporation was started on 25 January 1951, describing itself as “a distributor of the Western Arms Corporation”. The connection was never again publicly mentioned but obvious; for many years their mailing addresses were next to each other on Pico St in Los Angeles. In all likelihood, Winfield was the revenue-generation arm of the business, with Western concentrating on the darker side; as Western stopped running ads in January 1954.

As seen in the June 1953 ad above, a cornerstone of Winfield’s inventory was the Johnson Model 1941 semi-auto .30-06 rifle, an intended competitor of the M1 Garand. Rejected by the US Army, it was instead ordered by the Netherlands East Indies but never delivered due to the Japanese occupation. Under the spurious designation M1941 (not to be confused with the legitimate Johnson M1941 machine gun), some of these were used by US Marine Corps airborne units during WWII. The USMC airborne units disbanded in 1945 and the rifles were warehoused at MC Depot San Diego.

Less those lost in WWII, and a small batch finally delivered to the Netherlands afterwards, Winfield bought all 30,000 of these rifles from the government in 1953, then bought all remaining spare parts from Numrich, effectively becoming the sole source. Some were sporterized, others left in military appearance. These rifles were marketed as simply “The Johnson”. These were sold by Winfield it’s entire existence, including a small sale back to the CIA for use in the Bay Of Pigs fiasco.

The above advertisement from 1954 also shows rechambered .270 Winchester and .280 Remington (“7mm”) options for Winfield’s Johnsons.

One of Winfield’s earliest ads, from 1952, shows a “Dutch Mannlicher”. More formally the Netherlands M.95, this bolt-action 6.5x53mm(R) was probably the worst standard battle rifle of any WWII army. Along with it is a Hembrug M.73, an equally awful 9.4mm sidearm of the Netherlands army. Most likely, these were acquired in either the Netherlands Antilles or Dutch Guyana, the Netherlands two colonies in the western hemisphere. During WWII the USA equipped the Free Dutch forces there and these guns were quickly disposed of after the war. Westfield’s grading of the Hembrugs was maybe optimistic, for many carry a IB stamp (inwendig beroest / internal rust) to show that inspectors were doing their job. Besides the vintage bayonet is a M1917. These .45ACP revolvers, made in separate versions by Smith & Wesson (as here) and Colt, backed up production of the semi-auto M1911 during both world wars. Winfield rechambered some to .45 Autorim and .45LC, to eliminate the hassle of needing half-moons for the rimless .45ACP.

In the 1957 Winfield ad above, the German 98k is featured. These were probably easy to procure; as of the original 12 member nations of NATO, 7 had been occupied by the Third Reich during WWII. The “British Combat Revolver” shown is a Webley Mk.I, more associated with WWI but still used in WWII. Winfield rechambered them to .45ACP with half-moons for this rimless cartridge. These rechambered Mk.Is were not liked by most people who bought one. The other guns are evidence of another side of the “black” CIA effort, which did not limit itself to the famous guns of WWII. Countries which sat out WWII were rearming with now-inexpensive surplus Garands and Stens, and there were many bolt-action rifles and six-shooters coming onto the worldwide arms market. For example, Western made deals with the Costa Rican army and Irish State Guard. The “Martini Marksman” shown is a .357 Magnum version of the old Martini Mk.I carbine. Made by Birmingham Small Arms in the UK, these were popular in Australia and maybe part of a 1953 buy from that country.

The above 1958 advertisement from Winfield shows a WWII German 98k, a Swedish Gevär m/1938 of the WWII period, a very old Swiss Vetterli 10.4mm rimfire, a British WWII Enfield No.2 revolver, a M1903 Springfield, a WWII British Webley Mk.VI, a WWII-era Swedish m/94 carbine, a WWII British No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine, a WWII British SMLE No.4 Mk.I, and in the happy owner’s hands, a WWII British SMLE Mk.III. Along with an unrelated company (Santa Fe Arms), Winfield was one of the major importers of the Jungle Carbine, which is generally considered the worst of the Enfield family.

In the above 1959 ad is an Astra 400, the standard sidearm of Franco’s nationalists during the 1936-1939 civil war. Having sat out WWII, Spain was still somewhat isolated in the 1950s and was willing to sell guns to anybody with cash in hand. The excellent Astra 400 fired the 9mm Largo cartridge, which wasn’t common in the 1950s USA (nor today). Besides the silly repro pistols and the old Swiss gun, all the rest of the weapons are WWII.

The CIA’s effort to dry up small arms predictably failed as bad as the OSS’s effort to spread them had. Even at the start it would have been an uphill struggle. The wildcard was the USSR. In 1945, spread of Soviet WWII small arms was generally limited to the Red Army’s furthest advances in 1945. But ten years later, aggressive exporting had seeded Mosin-Nagants and PPSh-41s everywhere from Mongolia to Syria to central Africa. There was no longer any point to the project and Western Arms disappeared in the late 1950s, with Winfield following in 1963.

Surprisingly, the warehouse Winfield had expanded into on Olive St in Los Angeles, now boarded-up, still retains it’s signage as of 2016.

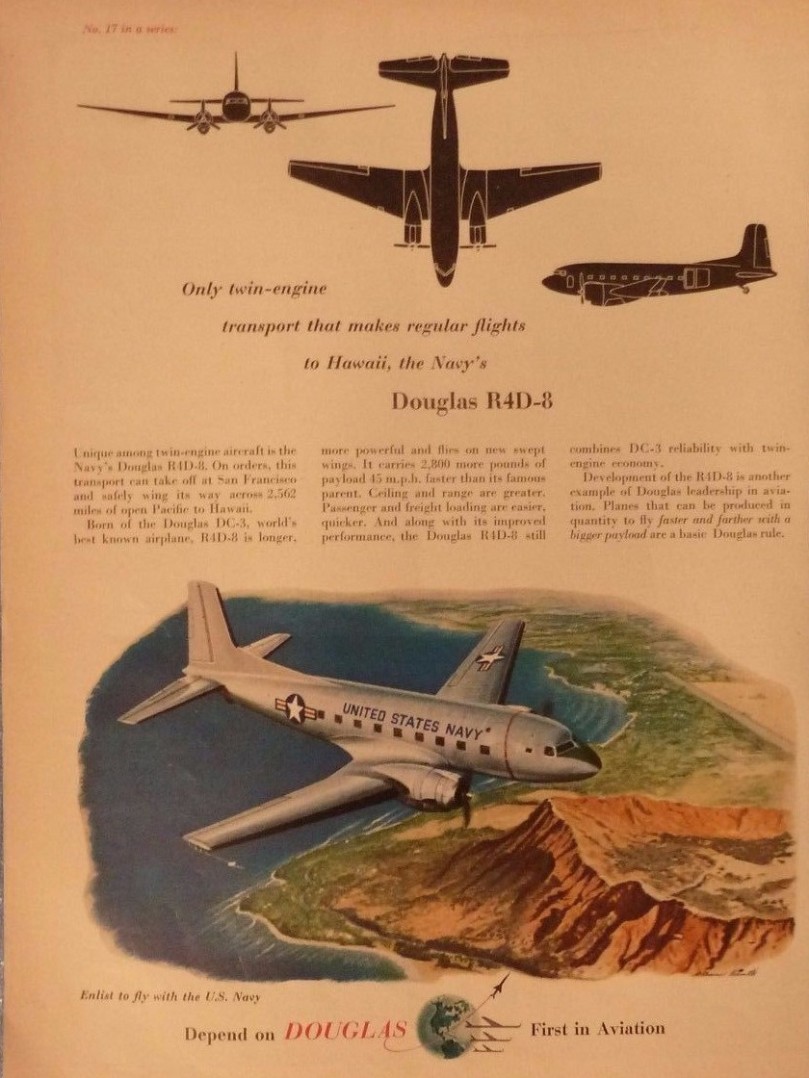

DOUGLAS (1953)

The above advertisement by Douglas aircraft ran in Life magazine during 1953. After WWII, the US Navy upgraded a hundred wartime R4D (C-47) Skytrains to the “super three” configuration with added capacity and range. The fuselage was stretched rearwards 3’5″, allowing one extra seating row. Larger tail surfaces were fitted, powered landing gear doors were added, and the engines were changed to two Wright R-1820 models. Altogether, Douglas claimed that the R4D-8 was “a 60% new airplane” compared to WWII-built R4Ds. This was technically true, if any and all minor changes were tallied up, and it was probably a necessary claim as during the late 1940s there was a prohibition casually adhered to in Congress against designs which had just seen orders cancelled in the V-J Day round of budget cuts.

The US Navy’s R4D-8 designation (also used by the Marines and Coast Guard) equated to the US Army and US Air Force’s C-117 slot; both being parallel to Douglas’s DC-3S commercial trademark. In 1962 all five branches of the American military unified their aircraft designation systems and the R4D-8 became the C-117D.

The conversion project advertised above was pitched to Congress by both the US Navy and Douglas as a value to wring more use out of WWII-surplus assets. As the effort proceeded, Congress generally soured on the effort. Each upgrade to these WWII-used transports cost $250,000 ($2.3 million in 2016 money). Meanwhile a larger, brand-new postwar C-131 cost $570,000.

For Douglas, sponsoring the advertisement to the general public was a way to encourage airlines to buy upgrades or even brand-new DC-3Ss. In the end the DC-3S program was a commercial flop. The USA’s airline market was flooded with surplus C-47 Skytrains, C-46 Commandos, and C-56 Lodestars after WWII; on top of the ever-trusty DC-3 which was still in wide airline use from before the war. Small airlines saw no value in the slightly improved traits of DC-3S planes compared to cheap war surplus transports. Meanwhile larger airlines like Eastern, United, and TWA bought the new very big post-WWII airliners like the Lockheed 749 or Douglas’s own DC-6.

(A US Navy C-117D on the tarmac at NAS Patuxent, MD in 1966.) (photo by Stephen Miller)

The C-117D continued in US Navy use for a surprisingly long time. The last was not retired until the Bicentennial in July 1976. From the mid-1950s onwards, they were often used as admiral shuttles, as the old-time officers preferred riding in the familiar DC-3 layout. C-117Ds were also used by the US Navy to support it’s Antarctic research effort.

(The newest and oldest members of the USA’s Antarctic research effort at the end of the 1960s, a US Air Force C-141 Starlifter and a US Navy C-117D.)

Douglas merged with McDonnell in 1967. McDonnell-Douglas itself was bought by Boeing in 1997 and the name vanished.

BOWER ROLLER BEARINGS (1955)

The US Navy’s aircraft carrier force at the end of WWII was second to none, however by the end of the 1940s it faced the challenge of adapting the wartime Essex class to Cold War jets. As Bower Roller Bearings 1955 ad states, the margin for error was none, as jets had a sharper approach slope and much higher minimum landing speed than the WWII propeller fighters the Essex class was designed for.

USS Shangri-La (CV-38) completed the $7 million ($64.1 million in 2016 dollars) SCB-125 refit in 1955, just in time to be featured in this ad. The SCB-125 project was applied to various Essex class aircraft carriers in the 1950s. Along with an enclosed bow and air conditioning, the most noticeable difference was an angled flight deck that allowed jets to more safely land, and stronger arresting wires to safely stop them.

(Comparison of the WWII original and SCB-125-modified Essex class.)

USS Shangri-La served until 1970 before being mothballed. During his first term in office, President Reagan proposed reactivating the WWII-veteran ship as part of his 1980s naval buildup, but was rejected by Congress. The carrier was scrapped in 1988.

As for Bower, who manufactured various types of complex bearings for the military, the company merged with Federal Mogul in 1985 and was spun off into a new company called NTN-Bower in 1987. It remains in business.

BARIUM STEEL CORPORATION (1955)

The above ad by Barium Steel Corporation ran in metalurgical and aviation trade journals in 1955. Ten years past the end of WWII and two years past the end of the Korean War, new Cold War weapons were ballooning in cost and an important part of any defense supplier’s reputation was it’s ability to cap production expenses. Companies like Barium touted their experience in having done this during WWII.

The warplane pictured is the P-80 Shooting Star, the second American WWII jet fighter after the P-59 Airacomet and the first to see mass production and frontline squadron service. Along with the ill-fated XP-79 flying wing fighter, the P-80 was one of the earliest designs to incorporate fused magnesium alloy skin in preference to riveted aluminum panels.

(The XP-80 prototype during WWII.)

During the spring of 1945, some P-80s were dispatched to Europe in the hopes of countering the Luftwaffe’s Ar-234 jet bombers. As it turned out, the two jets never met one another and the P-80 saw no combat during WWII.

This was not true during the Korean War, where the Shooting Star (redesignated from P-80 to F-80 after the US Air Force became an independent service) saw significant combat, both as fighters and attack planes, as seen below.

Barium Steel did not have long to live after this ad ran. The company went out of business in 1959.

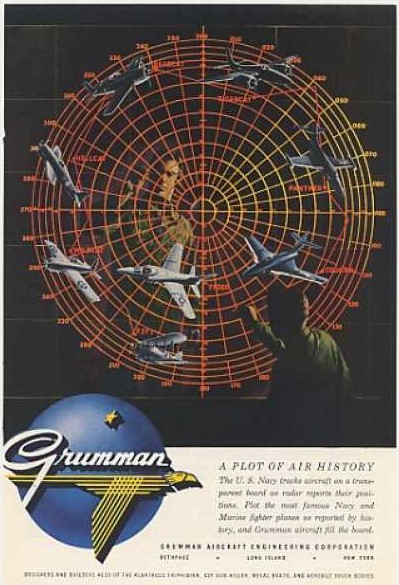

GRUMMAN (1955)

Grumman, the legendary supplier of naval aircraft to the US Navy, ran the above ad in 1955. It showcases their carrier fighter successes up to the time: clockwise; the pre-WWII F3F biplane, then the F4F Wildcat and F6F Hellcat of WWII fame, the F8F Bearcat which entered service towards the end of WWII but saw no combat, the F7F Tigercat which barely missed WWII use, then the postwar F9F Panther, F-9 Cougar, and F-11 Tiger jets.

The advertisement, which ran in specialized defense publications, had several layers of meaning. Foremost, obviously Grumman sought to tout it’s well-deserved good reputation.

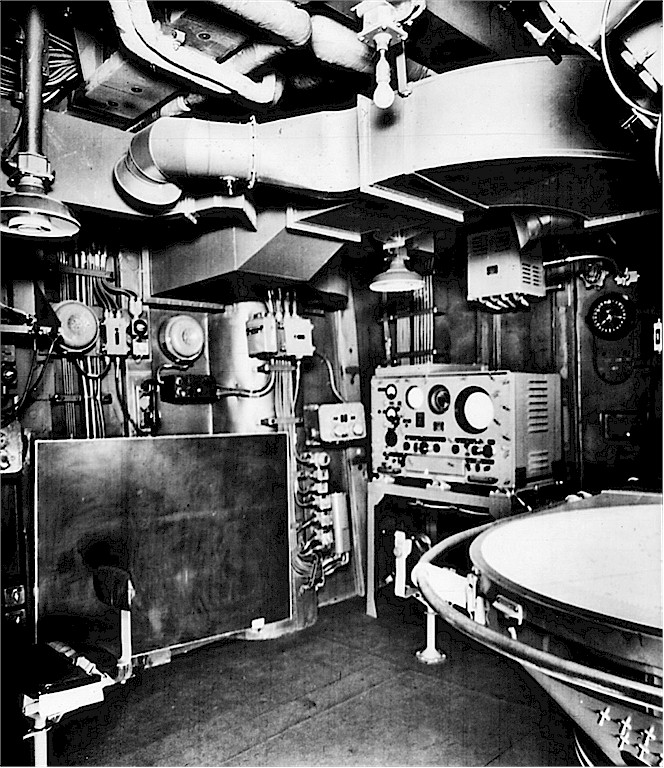

The grid plot is like the ones which might be found in a US Navy warship’s Combat Information Center (CIC) during that era. The CIC was a WWII innovation of tremendous importance. When WWII started, American captains expected to conduct battles from the ship’s bridge, much as Commodore Dewey had done aboard USS Olympia when he smashed the Spanish navy in 1898. After the Guadalcanal engagements where American captains suffered from “information overload”, a new approach was tried. A compartment protected deep inside the ship was fitted out as a “brain”, combining data from the vessel’s radar, sonar, radio, and aircraft and issuing orders to weapons mounts and navigation stations. For the first time, captains would fight battles without visually watching what was going on.

The CIC concept showed promise during the Coral Sea battle and even more during the Midway engagement. By the end of WWII in 1945, existing warships from frigates up to aircraft carriers had CICs added, and new classes were designed with a CIC from the start.

(The CIC of a Sumner class destroyer during WWII.) (photo via Navsource website)

During the Korean War and afterwards, CICs aboard WWII-built ships were constantly updated with the latest systems. Along with other features in these ships, CICs enabled classes like the Gearing destroyers and Essex aircraft carriers to remain relevant during the Cold War even as WWII British and Soviet classes of similar displacement faded away. By the mid-1950s, anybody hoping to sell anything to the US Navy was expected to fully understand and embrace the CIC concept, and here Grumman showed that they indeed did.

Finally, Grumman was making a point that it had been a success before, during, and after WWII and was not going anywhere. By the 1950s companies like Curtiss, Berliner-Joyce, and Brewster (all of which had operational planes in the US Navy’s inventory when WWII started) had vanished. Grumman hoped that any future export customer could feel assured that spare parts and technical support would not be an issue down the road.

(Uruguayan F6F Hellcat fighters in the 1950s.)

Grumman continued designing carrier planes during the Cold War, most notably the F-14 Tomcat. A 1994 mega-merger with Northrop resulted in the current company, Northrop-Grumman.

HEWITT ROBINS (1955)

One of Grumman’s post-WWII products, the F9F Panther, is shown in the above 1955 advertisement by hose maker Hewitt Robins. Operating from the hangars and decks of WWII-built aircraft carriers, jets of the Korean War era were larger and configured differently than WWII propeller types. At the same time, the speed and potency of modern strike jets and air-to-surface rockets made idle planes on the flight deck all the more dangerous. Here, Hewitt Robins advertised a new design of pressure-refueling hose compatible with both the new jets and the WWII-built Essex class ships.

Hewitt Robins went through a series of mergers and buyouts during the late 1960s and 1970s, finally being closed down completely in 1999. The current mining equipment company HR International was founded by ex-employees but is not a direct descendant.

DETROIT DIESEL (1957)

More so than tanks, rifles, and especially aircraft; warships of WWII were the longest-lived military assets during the Cold War. These WWII veterans either remained in use, went to mothballs and often later reactivated, or were sold abroad.

As years passed, the WWII engines on these vessels began to wear out. Especially in the case of WWII-built service vessels, tugboats, and amphibious craft; they had been built as fast as possible during the war with (understandably) little concern of what would happen to them down the road. Many of these minor types were designed as “semi-disposable”, but were surprisingly resilient and continued in use for decades after WWII.

The above trade show pamphlet from 1957 showcased the then-new 12V-71 engine of GM’s Detroit Diesel division. This engine was designed, in part, as a “drop-in” replacement for various types of WWII marine diesels.

The US Navy’s nameless LCI(L)-1091 is an example of a successful re-engining. Commissioned in September 1944, this infantry landing craft took part in the Okinawa battle and then the delivery of the occupation force in Japan. LCI(L)-1091 later served at the “Crossroads” atomic bomb tests, then as a mobile epidemic disease lab, and finally again in the amphibious role during the Korean War.

LCI(L)-1091 was originally completed with General Motors 6051 diesels during WWII, but later re-engined with the 12V-71 type shown in the ad.

Detroit Diesel was originally an internal division of General Motors formed in 1938. In 1988, it became a stand-alone company, until 2006 when it was acquired by the German company Daimler. As of 2016 Detroit Diesel continues to exist as a separate division inside Daimler.

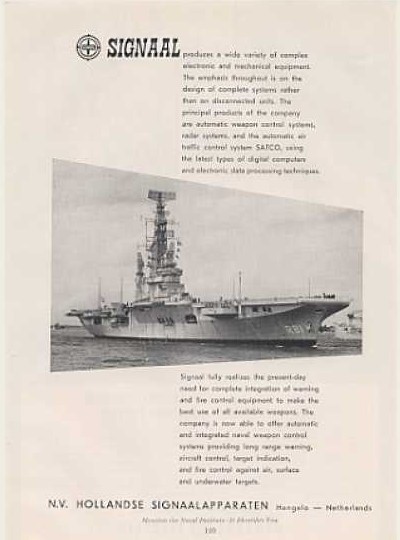

SIGNAAL (1959)

The Dutch military electronics firm Signaal ran the above advertisement in specialized naval journals and arms expo flyers in 1959. The aircraft carrier is the Dutch navy’s Karel Doorman, which had formerly been the Royal Navy’s HMS Venerable during WWII. This large and expensive carrier fell victim to the Royal Navy’s post-WWII budget cuts and in 1948 was sold to the Netherlands.

Signaal was a tremendously successful Dutch company. It was originally founded as one of Wiemar Germany’s “shadow companies” around Europe, developing military equipment banned by the Versailles Treaty. After WWII, it centered on naval sensors and saw phenomenal growth. Besides supplying the Dutch navy, Signaal carved out a niche as an “aftermarketer”, fitting radars and sonars on hulls of British, American, Canadian, and French origin; often aging WWII-era ships. The company sold radars around the world, filling a need for high-end sensors that the USA and USSR were sometimes unwilling to export. The advertisement shows Karel Doorman after a major upgrade in 1958 which saw Signaal products replace all the WWII-era British electronics: Signaal’s huge LW-01 radar visible atop the mainmast, along with secondary air and surface search radars, and a ZW-01 navigation radar.

Signaal’s strategy was successful and by the 1970s, it’s radars and sonars were all over the world. As for Karel Doorman, in 1968 the WWII carrier suffered an engine fire and was decommissioned, repaired, and sold to Argentina as ARA Veinticinco de Mayo. The carrier was the Argentine flagship during the 1982 Falklands War. Afterwards, a series of mechanical problems sidelined the ship. A refit in the late 1980s briefly returned ARA Veinticinco de Mayo to service, but age quickly caught up with the WWII vessel again and the carrier sat broken down in port through the 1990s, before being scrapped in 1999.

(ARA Veinticinco de Mayo makes A-4 Skyhawk jets ready during the 1982 Falklands War. An Argentine pilot had already painted his target’s name on one of the American-made bombs. As it turned out, a combination of weather, distance, and timing prevented the Argentine carrier from ever attacking the British fleet.)

Signaal was bought by the French company Thomson-CSF in 1990. In 2000, the former Signaal division was renamed Thales Nederland and the name went extinct.

HATCH & KIRK (1973)

The above ad by Hatch & Kirk ran in the grand-daddy of all specialized naval publications, Jane’s Fighting Ships, in 1973. This company was founded at the end of WWII by two friends who worked together at Todd Shipyard during the war. After the war’s end, they began purchasing naval diesel engine parts from warships being decommisioned; cataloging and storing them; and offering them for resale to support WWII-built warships still in use with the same engines.

The importance of a company like Hatch & Kirk during the Cold War can not be overstated. By the time this ad ran, many of the engine manufacturers the company supported were gone: Joshua Hendy in 1947, Atlas in 1951, Gray Marine in 1967, Enterprise in 1969, Baldwin in 1972. Even though the companies no longer existed, their WWII engines did, and needed spare parts.

(USS Nihoa (YFB-17) commissioned at Pearl Harbor one month before the 7 December 1941 Japanese attack. Used as a ferry to Ford Island, USS Nihoa was actually in motion when the Japanese appeared overhead but escaped undamaged. USS Nihoa is shown here in the late 1950s, with a WWII Essex class carrier in the background after it’s Cold War SCB-125 modernization. USS Nihoa served until 1961, still with her original Atlas diesel, ten years after that company vanished.)

(Originally a landing craft, YFU-54 put men ashore on Gold Beach during the invasion of Normandy. Like many American ships of WWII, Gray Marine diesels were used, in particular the 64HN9 model mentioned by name in the advertisement. For the Vietnam War, the old vessel was resdesignated as a harbor utility craft (YFU). This 1968 photo in South Vietnam was taken several months after Gray Marine ceased operations.)

Other manufacturers listed in the advertisement still existed at the time but had long since obsoleted WWII-era models. A good example is the extremely common General Motors Electromotive Division 12-567 naval diesel used on a huge number of WWII warships.

While GM obviously still exists, production of the 12-567 ended in 1966. It’s successor, the EMD 645, had some (but not complete) spare parts overlap but it itself left production in 1983; at which time there were still a decent number of old 12-567s powering WWII-vintage warships transferred to foreign navies during the Cold War.

(The Thai navy’s decommissioned HTMS Pangan in 2011, formerly the USS Stark County (LST-1134) of the US Navy in WWII. Like many LSTs of WWII, HTMS Pangan used General Motors 12-567 diesels.)

Hatch & Kirk was, and is, a well-run company which provided a valuable service. Besides collecting, cataloging, and reselling parts, it eventually began manufacturing some itself, especially for the old 12-567 engine. Hatch & Kirk continues in business as of 2016. Below is their branch office in Alton, IL in 2015.

Post war many Ex RAF aircraft found their way to the Middle East and in particular to the Israelis. Smaller fractions and developing countries also found themselves able to buy cheaply, a whole range of vehicles and weapons that were now surplus to requirements. An in interesting follow up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] via Postwar advertising legacy of WWII — wwiiafterwwii […]

LikeLike

I totally expected the Western Arms segment to end with Lee Harvey Oswald.

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOL

LikeLike

Hey man! Just left you a comment on your author page about attributing to you on The Firearm Blog. Excellent article!

LikeLike

Yes no problem!

LikeLike

[…] Source […]

LikeLike