Of the whole Lee-Enfield family, the No.5 Mk.I is probably the most obscure variant to enter production, and was certainly the least successful. Only seeing action in the final part of WWII, it went on to have a fairly long postwar career around the world.

(A No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine as used by British troops during WWII in 1945, and carried by a Kenyan game warden in 2008 showing the distinctive buttpad.)

Description

The No.5 Mk.I was 3’3½” long and weighed 7 lbs with an empty magazine. Like all of the Lee-Enfield family, it was a bolt-action rifle. Compared to the Enfield No.4 rifle from which it was developed, the No.5 Mk.I was 4″ shorter overall, and weighed 2 ¼ lbs less.

(A regular Enfield No.4 rifle, for comparison.)

(A regular Enfield No.4 rifle, for comparison.)

(The Enfield No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine.) (photo by David Tong)

(The Enfield No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine.) (photo by David Tong)

To achieve weight reduction, every idea was used. Compared to a regular Enfield, the upper wood forestock was deleted entirely, along with it’s now-unneeded forward metal retaining band. The lower wood furniture was narrowed and reduced in length by about half, leaving 7″ of the barrel exposed. The butt was slightly reduced in length and size, and capped with a thin metal buttplate. The rear sling attachment was buried into the right side of the buttstock instead of being bolted underneath it, removing a bit more wood and weight. Interestingly there were three “sizes” of butt shapes issued, matching the soldier’s stature.

Besides being shorter than a regular Enfield barrel, the barrel on the No.5 Mk.I was also slightly thinner. To the rear, the barrel was reworked to what was called “Knox form”, with scallops of metal being shaved off where not necessary for strength.

(Areas of removed metal on the rear part of the barrel and ejector port.)

(Areas of removed metal on the rear part of the barrel and ejector port.)

Further metal was removed on the right side of the action, the trigger guard was of thinner metal, and even the bolt handle knob was hollowed-out and truncated.

Internally, some metal was shaved off the butt socket and lightening cuts were made into the receiver’s lugs and the left receiver wall. Clearly any possible thing to reduce the weapon’s weight was done.

Internally, some metal was shaved off the butt socket and lightening cuts were made into the receiver’s lugs and the left receiver wall. Clearly any possible thing to reduce the weapon’s weight was done.

The No.5 Mk.I was fed from a 10-round detachable box magazine, and fired the .303 British cartridge.

This cartridge, specifically the WWII-common Mk.VII version which was normally used with the Jungle Carbine, had a 174-grain full metal jacket spitzer bullet with a combination lead / aluminum core. The light aluminum in the nose resulted in a tail-heavy performance after impact, causing more severe wounds. The Mk.VII .303 round had a muzzle velocity of 2,440fps and like many WWII-era rifle rounds, was a bit overpowered for it’s intended role. The Jungle Carbine could also use older WWI-era .303 Mk.VI rounds however by 1945 few of these were still in regular use. It could also fire the .303 Mk.VIII cartridge which was intended for machine gun use; however the British discouraged this as it was discovered that this bullet tore up the rifling in the No.5 Mk.I’s barrel.

This cartridge, specifically the WWII-common Mk.VII version which was normally used with the Jungle Carbine, had a 174-grain full metal jacket spitzer bullet with a combination lead / aluminum core. The light aluminum in the nose resulted in a tail-heavy performance after impact, causing more severe wounds. The Mk.VII .303 round had a muzzle velocity of 2,440fps and like many WWII-era rifle rounds, was a bit overpowered for it’s intended role. The Jungle Carbine could also use older WWI-era .303 Mk.VI rounds however by 1945 few of these were still in regular use. It could also fire the .303 Mk.VIII cartridge which was intended for machine gun use; however the British discouraged this as it was discovered that this bullet tore up the rifling in the No.5 Mk.I’s barrel.

The Jungle Carbine was loaded by 5-round stripper clips with the bolt all the way back.

(Proper method for loading the No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine. The small switch at the front of the trigger guard is the magazine release.)

(Proper method for loading the No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine. The small switch at the front of the trigger guard is the magazine release.)

The barrel was fitted with a cast-iron conical flash suppressor, which was definitely needed as using standard .303 British ammo with the now-shortened barrel generated an impressive muzzle flash. (Contrary to the common notion, flash suppressors do not “hide” the flash from the enemy but rather reduce shooter disorientation.) The flash suppressor was press-fitted to the barrel in an assembly which included the fixed forward blade sight and it’s protectors, and the bayonet lug.

An adjustable rear sight similar to a regular Enfield No.4’s was used. In theory, the maximum range should have been 2,500 yards however this was obviously unachievable with a carbine. The No.5 Mk.I sight was graduated in 100-yard increments and topped out at 800 yards which was itself extremely optimistic.

An adjustable rear sight similar to a regular Enfield No.4’s was used. In theory, the maximum range should have been 2,500 yards however this was obviously unachievable with a carbine. The No.5 Mk.I sight was graduated in 100-yard increments and topped out at 800 yards which was itself extremely optimistic.

The No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine was unique in that it was the only member of the whole Lee-Enfield family to use a bowie style bayonet. For weight reduction in the airborne role, the Wilkinson No.5 was selected; as it was intended that the paratroopers would use it both as their bayonet and to replace their standard Fairbairn-Sykes combat knife. The No.5 bayonet could only be used with the Jungle Carbine and the Sterling submachine gun.

The No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine was unique in that it was the only member of the whole Lee-Enfield family to use a bowie style bayonet. For weight reduction in the airborne role, the Wilkinson No.5 was selected; as it was intended that the paratroopers would use it both as their bayonet and to replace their standard Fairbairn-Sykes combat knife. The No.5 bayonet could only be used with the Jungle Carbine and the Sterling submachine gun.

Functionally, there was not much different between the Jungle Carbine and the other Enfield versions. It shared the same enjoyable smooth, easy bolt motion.

Functionally, there was not much different between the Jungle Carbine and the other Enfield versions. It shared the same enjoyable smooth, easy bolt motion.

Use during WWII

The first combat use of the No.5 Mk.I was during the September 1944 “Market Garden” airborne operation at Arnhem in the occupied Netherlands. Later in Europe, British troops used in in the final push towards Hamburg at the end of the war. Overall, the No.5 Mk.I did not see a lot of use in Europe.

In the Pacific, British units fighting in the CBI theater began to receive the weapon towards the end of 1944. During 1945, British troops used the No.5 Mk.I during fighting in April against the Japanese 49th and 53rd Divisions north of Rangoon in Burma. It was here that the weapon’s “jungle” connotation started. Larger issuance was scheduled for operation “Zipper”, the large planned late-1945 liberation of Singapore and the lower Malay peninsula, which was cancelled after the Japanese surrender and end of WWII.

Advantages and Problems

The No.5 Mk.I achieved most of it’s “on-paper” goals, namely being a smaller, lighter weapon that none the less delivered the punch of the regular Enfield. It didn’t add any additional strain to Britain’s logistics system. For certain, soldiers in the jungle appreciated the lighter weight, and the .303 British’s ability to go through dense foliage and bamboo.

Unfortunately the Jungle Carbine also introduced a number of it’s own problems. The first was a matter of simple physics: when using the same cartridge as the heavy Enfields, but with a much lighter mass to counteract it, felt recoil increased greatly. To say that the No.5 Mk.I’s kick was strong is an understatement; it was absolutely punishing. Much greater than a Mosin-Nagant or M1903 Springfield, it was only a few rungs on the ladder below an African safari gun.

The buttpad design was a failure. The designers had originally intended it to serve as a non-skid mate to the shooter’s shoulder in wet conditions, not for recoil abatement. For unknown reasons, it was made narrower than the buttplate, which simply concentrated the per-inch pressure like a wedge rather than dissipating it. The original rubber was rejected by the British army for fears it would rot, and instead a denser, less-effective type of rubber was used. After time it hardened up even more, and in the end it was worthless at best, and at worst, made shooting the Jungle Carbine even more painful than with no pad at all.

The buttpad design was a failure. The designers had originally intended it to serve as a non-skid mate to the shooter’s shoulder in wet conditions, not for recoil abatement. For unknown reasons, it was made narrower than the buttplate, which simply concentrated the per-inch pressure like a wedge rather than dissipating it. The original rubber was rejected by the British army for fears it would rot, and instead a denser, less-effective type of rubber was used. After time it hardened up even more, and in the end it was worthless at best, and at worst, made shooting the Jungle Carbine even more painful than with no pad at all.

The wandering zero issue

The inability (or alleged inability) of the No.5 Mk.I to “hold zero”, or stay accurate from one day to the next after being sighted in, is perhaps what the Jungle Carbine became most famous for and is what caused it’s eventual downfall.

The problem was first noticed during the “Market Garden” operation in 1944, and by the end of WWII in 1945 was being commented on by every unit that used the Jungle Carbine.

The problem is still widely disputed today among firearm experts. There is a small faction that believes every Jungle Carbine was affected as it’s design was bad, and an opposite small faction that believes the problem never even existed at all. A larger group falls in the middle, believing that the problem probably existed but was not necessarily universal, and/or that the problem was blown out of proportion by the British in the late 1940s as they were looking for an excuse to retire WWII-era gun designs in favor of buying new assault rifles.

Modern bench tests have proven that at least some No.5 Mk.Is hold their zero perfectly fine. On the other hand, recollections of British veterans regarding the problem are widespread enough that it wouldn’t seem to be made up, either.

Between 1945-1947 the British tried to solve the problem or at least identify a cause. One theory was that the shortened wood furniture was swelling from moisture, to that end some No.5 Mk.Is manufactured in 1946 and 1947 have a metal cap on the front of the lower forestock. The wood itself was usually birch or some other cheap lumber, as Britain was running short of walnut by the end of WWII, and this was sometimes cited as a theory. Another theory was that the thinner, smaller barrel was insufficient to dissipate heat and that the barrel would minutely distort. Yet another theory was that the lightening cuts in the receiver were the problem. It’s possible that all these issues contributed, or, that none did and that it was something else entirely. Various fixes were tried, none to any effect. In 1947, the British government stated that it was unable to pinpoint the cause and that the design was “inherently flawed”.

Production

Royal Ordnance Factory’s Fazakerley facility made 170,000 of these guns and Birmingham Small Arms made 87,000 at their Shirley plant. A license was issued to Canada in 1945 but with the end of WWII planned production there was cancelled and very few were made in Canada. The whole production run was short but intense: the first were manufactured in March 1944, and all production was terminated in December 1947 as a result of the wandering zero problem.

BSA Shirley also manufactured a small number of these guns chambered in .22LR during 1945-1946. It was proposed that this would become the standard postwar boot camp training rifle, but with the problems of the regular version this idea was dropped.

“Jungle Carbine” was never an official British military designation. During WWII, soldiers in Burma sometimes called the No.5 Mk.I the “jungle carbine”, and during the Malay Emergency it greatly became associated with jungle use. During the 1950s, Santa Fe Arms in the USA imported some surplus No.5 Mk.Is and advertised them as “Jungle Carbines” to spice up their appeal to civilian shooters, and the name stuck worldwide thereafter.

POST-WWII USAGE

Great Britain

The British continued to use the No.5 Mk.1 after WWII, and in fact, briefly planned to make it the army-wide firearm, replacing all the earlier Enfield versions. The curtailment of production in 1947 and the wandering zero issue prevented that, however it did see further British combat use after WWII.

Operation Doomsday (1945)

This operation was undertaken after the end of WWII in Europe but before the end of the war in the Pacific. When Germany surrendered on 8 May 1945, the German garrison in occupied Norway was still almost completely intact, numbering over 220,000 fortified and fully-equipped troops controlling almost all of the country. German rule over Norway had been split between the Wehrmacht General Franz Bohme controlling military affairs, and a nazi official, Josef Terboven, in charge of political affairs. Terboven was a die-hard and had spoke of a “festung norwegen” (Fortress Norway) and fighting to the last man after the fall of Berlin in April. Therefore, the victorious Allies were uncertain of how the surrender of German troops would happen, or if they would even surrender at all.

The British 1st Airborne Division was selected to make the initial air landing at Oslo. By this time, the division had completely converted to the No.5 Mk.I.

Unbeknownst to the Allies, Admiral Karl Doenitz, in the few days he served as Hitler’s successor, had fired Terboven and placed Gen. Bohme in complete control. Bohme was a highly-disciplined professional officer, and ensured that his men strictly obeyed the surrender. Therefore the operation, which started two days after the end of WWII in Europe, was unopposed and uneventful.

(British paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division, carrying No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines, parade in downtown Oslo in May 1945.)

(British paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division, carrying No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines, parade in downtown Oslo in May 1945.)

The 1st Airborne Division remained in Norway until the end of August, when Norwegian control was sufficiently re-established. It had been planned to send the division to the Pacific to partake in the invasion of the Japanese home islands, but the end of WWII made that unnecessary.

Securing the Far East (1945-1947)

The sudden end of WWII after the two atomic bombings left a void across much of southern Asia, as the now-surrendered Imperial Japanese Army still controlled vast areas of European colonies, some already clamoring for independence. As the Dutch and French were in no position to send large units around the world at that time, British forces were employed to maintain colonial order.

(British troops in the Netherlands colony of Java (today in Indonesia) conduct a search for anti-Dutch rebels in 1946. The two infantrymen have No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines, while the officer on point carries an American-made M1911 which some British troops preferred to the Webley Mk.IV revolver.)

(British troops in the Netherlands colony of Java (today in Indonesia) conduct a search for anti-Dutch rebels in 1946. The two infantrymen have No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines, while the officer on point carries an American-made M1911 which some British troops preferred to the Webley Mk.IV revolver.)

These operations took place across the Netherlands East Indies and French Indochina, and additionally the small British contingent of the occupation force in Japan partially used No.5 Mk.Is.

(Ethnic Indian sappers (combat engineers) of the British Royal Indian Army in the Netherlands East Indies in 1946. They carry No.5 Mk.Is. When India became independent a year later, some of the BRIA’s units retained their British weapons, including the Jungle Carbines.)

(Ethnic Indian sappers (combat engineers) of the British Royal Indian Army in the Netherlands East Indies in 1946. They carry No.5 Mk.Is. When India became independent a year later, some of the BRIA’s units retained their British weapons, including the Jungle Carbines.)

Withdrawal from Palestine (1946-1948)

Great Britain inherited the area known as the Palestine Mandate after WWI. During WWII, the area saw little activity but in 1945, this changed as both Jews and Arabs wanted to establish independent nations in the area. The 6th Airborne Division (which had actually been the first division to equip with the No.5 Mk.I during WWII) carried Jungle Carbines almost exclusively, and some were also used by a commando team from Hong Kong and a battalion of the King’s Liverpool Regiment sent to back up the paratroopers.

(A British paratrooper with No.5 Mk.I stands watch in the Palestine Mandate after WWII, before it became the nation of Israel.)

(A British paratrooper with No.5 Mk.I stands watch in the Palestine Mandate after WWII, before it became the nation of Israel.)

In February 1947, Britain announced that responsibility for the Mandate would be turned over to the UN to deal with. Immediately, British forces in the Mandate conducted operation “Polly”, the guarded assembly and evacuation of Commonwealth civilians in the region. In December 1947, British troops used their Jungle Carbines to put down a riot between Jews and Arabs in Haifa. On 14 May 1948, the last British soldier left Israel. A few of the No.5 Mk.Is were left behind, but neither the Israeli nor Jordanian armies used the weapon much.

The Korean War (1950-1953)

The British contingent fighting in the Korean War was partially armed with No.5 Mk.Is but the standard versions of the Enfield (SMLE Mk.III and Enfield No.4) were more common. Australian troops fighting alongside the British as part of the “Commonwealth Force” were more likely to use the Jungle Carbine and little was said about it’s performance in Korea.

(Illustration from an American manual outlining Allied weapons in the Korean War.)

(Illustration from an American manual outlining Allied weapons in the Korean War.)

The Malay Emergency (1948-1957)

This conflict was the most well-known use of the No.5 Mk.I. Like the Korean War, the Malay Emergency involved both WWII-era and postwar weapons.

This conflict was rooted in WWII. When Japan overran Britain’s colonies on the Malay peninsula and Singapore in 1942, resistance split on racial lines between ethnic Malaysians and ethnic Han (Chinese). The Japanese occupation force viewed ethnic Malaysians as “liberated subjects of colonialism”, while the ethnic Han were viewed as de jure enemies and persecuted ruthlessly. Resistance amongst the Malaysians was muted, while the ethnic Han formed the overwhelming majority of the communist “People’s Anti-Japanese Army”. This marxist guerrilla army was a force to be reckoned with and was supported by the Allies up until mid-1945. With Japan’s defeat, the force renamed itself Malaysian People’s Liberation Army (MPLA) and rededicated itself now to ejecting the returning British and establishing immediate communist rule. At the same time, it purged all non-Han fighters from it’s ranks. The MPLA was opposed by (naturally) the British, and the United Maylays National Organization (UMNO) which was almost entirely ethnic Malaysian and muslim, and wanted a gradual transition to independence but with no rights for the Han, Indians, Thais, or any other minority. Heavy fighting began in 1948. The UK was supported by Commonwealth units from Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Rhodesia, and Britain’s dwindling African empire.

(The three most common British firearms of the Malay Emergency, all WWII-vintage weapons: The American-made M1 carbine, the Australian-made Owen submachine gun, and the No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine.)

(The three most common British firearms of the Malay Emergency, all WWII-vintage weapons: The American-made M1 carbine, the Australian-made Owen submachine gun, and the No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine.)

The No.5 Mk.I was immediately in large-scale use and by the end of the 1940s, was almost the exclusive longarm of Commonwealth forces fighting in the Emergency.

(Members of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry during the Malay Emergency, their guns (from point back) are an Owen submachine gun, a Bren machine gun, a Jungle Carbine, a regular Enfield modified for grenade launching, and more Jungle Carbines. All of these firearms were WWII weapons.)

(Members of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry during the Malay Emergency, their guns (from point back) are an Owen submachine gun, a Bren machine gun, a Jungle Carbine, a regular Enfield modified for grenade launching, and more Jungle Carbines. All of these firearms were WWII weapons.)

The Emergency was fought in the jungles of Malaysia and was well-suited to the No.5 Mk.i’s purpose, being light on long patrols and less likely to become entangled in jungle vegetation, while still delivering a formidable punch. Ranges out to about 200 yards were considered the realistic maximum, and the bolt-action Jungle Carbines were almost always backed up by submachine guns, usually Owens or Stens; sometimes Lanchesters and Sterlings.

(A soldier of the King’s African Rifles fighting in the Malay Emergency, armed with a No.5 Mk.I.)

(A soldier of the King’s African Rifles fighting in the Malay Emergency, armed with a No.5 Mk.I.)

(A unit of Royal Marines during the emergency, armed with No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines, the then-new L1A1 assault rifle, and Sterling submachine guns.)

(A unit of Royal Marines during the emergency, armed with No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines, the then-new L1A1 assault rifle, and Sterling submachine guns.)

In 1954, the new L1A1 assault rifle began to enter service with Commonwealth troops fighting the conflict. It’s 7.62mm NATO cartridge offered comparable performance to the old .303 British round, and the L1A1 did not have the vicious kick of the Jungle Carbine nor it’s “wandering zero” issue. None the less, the No.5 Mk.I continued in use.

(A Royal Marine during the final, mid-1950s stage of the conflict, armed with a No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine.)

(A Royal Marine during the final, mid-1950s stage of the conflict, armed with a No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine.)

(A unit of British infantry on patrol with a No.5 Mk.I, an Owen, another No.5 Mk.I, and a Sterling.)

(A unit of British infantry on patrol with a No.5 Mk.I, an Owen, another No.5 Mk.I, and a Sterling.)

The insurrection was largely under control when Malaysia became an independent nation in 1957, and Commonwealth forces began withdrawing. The departure of the British made the supposed “anti-colonialism” angle of the MPLA irrelevant and the force began to dwindle. In 1960, the Malaysian government declared the conflict officially over.

The Mau Mau Uprising (1952-1960)

The No.5 Mk.I saw use by British forces during this rebellion of native Africans in British East Africa (today, Kenya). For some of the Jungle Carbines used, it was already their third war, having seen action in WWII and the Malay Emergency.

(A British army unit on patrol in the African bush during the Mau Mau uprising. The first two men carry L1A1 assault rifles, the third a Sten Mk.V submachine gun, and the rest No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines. Like the Malay Emergency and the Confrontation in Borneo, the Mau Mau uprising saw mixed use of WWII-era and Cold War-era weapons.)

(A British army unit on patrol in the African bush during the Mau Mau uprising. The first two men carry L1A1 assault rifles, the third a Sten Mk.V submachine gun, and the rest No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines. Like the Malay Emergency and the Confrontation in Borneo, the Mau Mau uprising saw mixed use of WWII-era and Cold War-era weapons.)

The WWII-vintage Jungle Carbine was still effective in this 1950s conflict due to the very poor armament of the Mau Mau rebels, most of whom were armed with single-shot civilian hunting guns or bolt-action WWII relics.

(British soldiers man a checkpoint in Nairobi during the Mau Mau uprising, armed with No.5 Mk.1s. This photo shows the bayonet fitted.)

(British soldiers man a checkpoint in Nairobi during the Mau Mau uprising, armed with No.5 Mk.1s. This photo shows the bayonet fitted.)

By the middle and latter parts of the conflict, many regular British units had converted to the L1A1 assault rifle. However the King’s African Rifles continued to use it as their main firearm.

(An infantryman of the King’s African Rifles with a No.5 Mk.I during the 1950s Mau Mau uprising.)

(An infantryman of the King’s African Rifles with a No.5 Mk.I during the 1950s Mau Mau uprising.)

Established in 1902, the King’s African Rifles drew recruits from Great Britain’s colonies in eastern and southern Africa. The unit served in both world wars and the Malay emergency. During the Cold War, they were usually the last in line to get new gear and they retained a number of WWII weapons through the end of the 1950s. Perhaps the most famous alumnus after WWII was a young Idi Amin, who enlisted in 1946.

The King’s African Rifles dwindled as the UK’s African colonies became independent, and the unit was formally disbanded in December 1963, at which time it still had some Jungle Carbines in inventory. The armies of Kenya and Malawi were originally formed around units of this force and the modern Kenyan army still has a unit called the Kenyan Rifles.

Withdrawal from Aden (1967)

During the evacuation of of the Aden colony (today Yemen), a few old WWII-vintage No.5 Mk.Is were surprisingly in use by the withdrawing British forces. This was the last British use of the Jungle Carbine.

Overseas users

Australia

Few Australian units had been issued the No.5 Mk.I during WWII, however it was used by a small number of Australian units during the Korean War, and was one of the main weapons of Australian soldiers during the Malay Emergency.

(An Australian soldier with a No.5 Mk.I during the early 1950s. The metal cap on the front of the lower forestock, which was a failed attempt to fix the wandering zero problem, dates this Jungle Carbine to one of the lots made in late 1946 or early 1947.)

(An Australian soldier with a No.5 Mk.I during the early 1950s. The metal cap on the front of the lower forestock, which was a failed attempt to fix the wandering zero problem, dates this Jungle Carbine to one of the lots made in late 1946 or early 1947.)

The No.5 Mk.I was still in dwindling Australian use during the 1963-1966 Confrontation conflict with Indonesia on the island of Borneo. Australian troops served alongside British troops (who had phased the Jungle Carbine out by then) during the conflict. This was the last Australian use of the No.5 Mk.I as the Australian army had already begun to shift to the L1A1 assault rifle in 1959.

There is one interesting sidenote to the story of the Jungle Carbine in Australia. During WWII, the Australian army had also recognized the need for a shorter, lighter Enfield for jungle use, and a SMLE Mk.III (as opposed to the Enfield No.4) was modified with many of the features of the British creation. This firearm was designated Rifle No.6 Mk.I but very few were made.

Canada

The No.5 Mk.I had been issued to Canadian units in very limited numbers in 1945. The cancellation of the planned license production in Canada ended further adoption, however some Jungle Carbines were used by the Canadian contingent during the Korean War. The weapon was not popular in Canadian use, and the American-made M1 carbine was preferred. Canada switched to the C1 assault rifle in 1955.

India

When the Royal British India Army became the independent Indian army in 1947, some units which had been equipped with the No.5 Mk.I during WWII retained them for a number of years. However it was never a mainstay of the Indian army. After it’s withdrawal from military use, the Maharashtra State Police used them into the late 1960s.

Kenya

Kenya was one of the last countries in the world using the Jungle Carbine as a frontline weapon. When Kenya became independent in December 1963, the core of it’s small new army was formed around the defunct King’s African Rifles. The 1st Kenya Rifles battalion at Nanyuki is actually a direct carryover from the K.A.R. and was initially equipped with No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines, which the unit had used during the Mau Mau uprising while still part of the K.A.R. The neutral country quickly reequipped with more modern assault rifles sourced from West Germany, the USSR, and Israel; with the old Jungle Carbines being transferred into reserve. By the turn of the millennium the No.5 Mk.I was out of Kenyan army inventory completely, but as of 2015 is still used by game wardens where it’s light weight and the impressive stopping power of the .303 British round is appreciated.

Malaysia

Malaysia became independent on 31 August 1957, near the end of the Malay Emergency. As such, local units allied with the British formed the nucleus of the new army, equipped wholly with weapons inherited from the conflict including a large number of No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines.

(Malaysian troops, still with a British commander, near the end of the Emergency conflict in the late 1950s. They are all armed with WWII weapons: Sten submachine guns, a Bren machine gun, M1 carbines, and No.5 Mk.1 Jungle Carbines.)

(Malaysian troops, still with a British commander, near the end of the Emergency conflict in the late 1950s. They are all armed with WWII weapons: Sten submachine guns, a Bren machine gun, M1 carbines, and No.5 Mk.1 Jungle Carbines.)

The new country soon found itself at war again, this time against Indonesia in what was known as the “Confrontation”. Fought from 1963 to 1966, the cause of this conflict was Indonesia’s desire to annex the independent nation of Brunei and the UK’s British North Borneo colony, which joined Malaysia in September 1963. Indonesia had inherited it’s portion of Borneo from the Dutch and eventually hoped to rule the whole island.

The Malaysian troops were backed up by a Commonwealth force, mainly British, Australian, and New Zealander. Now largely forgotten, this was a fairly intense conflict which ranged from urban areas of Brunei, all through British North Borneo and Malaysia’s Sarawak province. On several occasions fighting spilled over into the Indonesian part of Borneo.

The Malaysian troops were backed up by a Commonwealth force, mainly British, Australian, and New Zealander. Now largely forgotten, this was a fairly intense conflict which ranged from urban areas of Brunei, all through British North Borneo and Malaysia’s Sarawak province. On several occasions fighting spilled over into the Indonesian part of Borneo.

The No.5 Mk.I was a key weapon of the Malaysian army during the conflict. By this time, the WWII bolt-action design was definitely showing it’s age against the semi-automatic and full auto rifles the Indonesians were using, but the new country of Malaysia was limited by finances as to how fast it could re-equip it’s army.

(Malaysian army unit equipped with No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines.)

(Malaysian army unit equipped with No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines.)

The conflict ended in Malaysia’s favor, with British North Borneo successfully joining Malaysia as the “autonomous area” of Sabah. This entity was supposed to have been a semi-sovereign area but by the end of the 20th century Sabah was basically a de facto province of Malaysia. Brunei remained independent.

After the Confrontation war, the Malaysian army began phasing out the Jungle Carbine. Many were passed to the Police Field Force, a paramilitary law enforcement force which was basically a light infantry unit trained for internal security duties in the jungle. The Police Field Force used the No.5 Mk.I into the early 1970s, and retained some in storage until the force was rolled into the Royal Malaysia Police’s new General Operations Force in 1997. Many Jungle Carbines which entered the worldwide sport shooting and collector’s markets in the early 2000s are ex-Police Field Force, identified by a letter “P” marking and two- or three-digit serial on the buttstock. Many of the ex-Malaysian No.5 Mk.Is had the bayonet lug removed.

New Zealand

Like Australia, New Zealand had received only modest numbers of No.5 Mk.Is during WWII but used the weapon heavily during the Malay Emergency in the 1950s and then again during the Confrontation in the 1960s.

(New Zealand army troops on patrol with WWII Jungle Carbines during the late 1950s.)

(New Zealand army troops on patrol with WWII Jungle Carbines during the late 1950s.)

New Zealand tries to keep it’s military aligned with neighboring Australia and phased out the Jungle Carbine at the same time as the Australians.

Rhodesia

The Rhodesian army was the last military to carry the WWII-era No.5 Mk.I into battle. Following it’s declaration of independence on 11 November 1965, the Rhodesian army was equipped with a wide variety of aging firearms, including WWII castoffs such as the No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine.

(Rhodesian army all-over OD green uniform of the Bush War’s “first phase” of 1965-1972, with No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine.)

(Rhodesian army all-over OD green uniform of the Bush War’s “first phase” of 1965-1972, with No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbine.)

The now-old WWII weapon was immediately at a disadvantage against the AK-47s used by ZANU, additionally by the 1970s the .303 British ammunition was no longer plentiful whereas the 7.62mm NATO round was widely available on the worldwide black market for embargoed Rhodesia. Therefore the country quickly standardized on the FN FAL assault rifle, and the Jungle Carbine faded from use. A few were still in use by farmer self-protection units as late as 1979.

Singapore

The story of the Jungle Carbine in Singapore is linked to the tiny island city-state’s unusual beginning. In 1959, the Crown Colony of Singapore was made “self-governing” within the British Commonwealth. On 16 September 1963, it became fully sovereign and joined the federation of Malaysia, Sarawak, and Sabah.

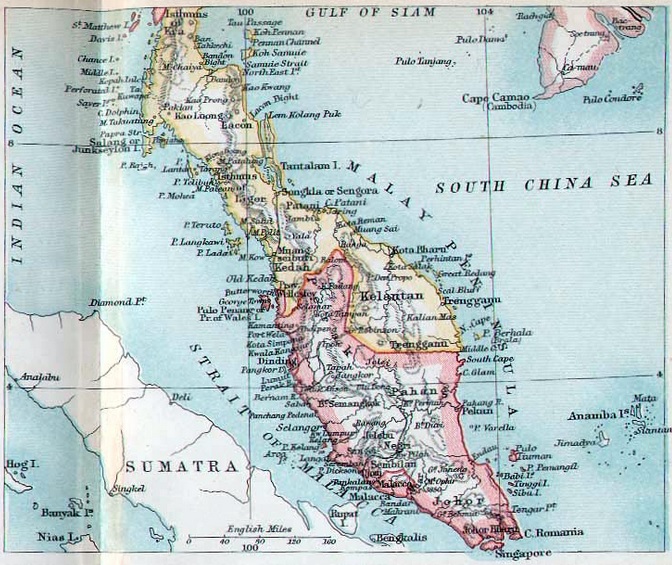

(A 1940s map showing the western (mainland) portion of what would become Malaysia, with Britain’s “peninsular Malay” colonies, the “straits settlements” colonies, and little Singapore at the bottom.)

(A 1940s map showing the western (mainland) portion of what would become Malaysia, with Britain’s “peninsular Malay” colonies, the “straits settlements” colonies, and little Singapore at the bottom.)

The integration of Singapore into Malaysia did not go as planned. Mainland Malaysian society was organized on ethnic Malay/Chinese lines, but Singapore has a mixed population of ethnic Malays, ethnic Chinese, some ethnic Indians and Thais, and a small community of Britons and Australians which stayed on. The island speaks English as it’s primary language and it’s people follow European customs and dress. When Singapore joined Malaysia, it brought it’s own political parties which did not align with the main parties in the rest of Malaysia.

A larger unspoken issue was that powerful interests in Malaysia feared that Singapore, which is only about the area of New York City, would dominate the whole country as Singaporean culture is oriented towards education and business; and the island already boasted an excellent merchant port. Therefore on 9 August 1965, Malaysia expelled Singapore from the country and the little island city became an independent country.

The completely sudden independence left the new country scrambling to arm it’s new military, which initially only numbered 1,800 men. It’s armaments were limited to whatever was already on the island in 1965, namely old WWII No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines left over in storage from the Malay Emergency of the 1950s or even from the reestablishment of British control after Japan’s surrender in 1945. Along with some regular Enfield No.4s and SMLEs, the No.5 Mk.I was Singapore’s first longarm.

These did not stay in use long, as by the end of the 1960s the rapidly expanding Singaporean army was re-equipping with modern American and Israeli firearms. The No.5 Mk.Is were passed on to the Singapore Police.

(A riot squad of the Singapore Police in the late 1960s, armed with WWII No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines. Polls of worldwide police chiefs consistently rate the Singapore Police as one of the world’s best police departments.) (photo via Getty Images)

(A riot squad of the Singapore Police in the late 1960s, armed with WWII No.5 Mk.I Jungle Carbines. Polls of worldwide police chiefs consistently rate the Singapore Police as one of the world’s best police departments.) (photo via Getty Images)

The Singapore Police used the No.5 Mk.1 into the late 1970s, when they were replaced by Remington 870 shotguns.

So much is wrong with this article it amazes me…

LikeLike

Hi Bill, I am always welcome to corrections; anything in particular?

LikeLike

No such thing as the “Royal Indian Army”; it was simply the Indian Army, even during the British imperial era.

LikeLiked by 1 person

During the Raj era, the British monarch was co-regent of the Commonwealth and of India. (Victoria actually had a second crown made for Empress/Emperor Of India. Royal Indian Army was the correct formal name of the force for the timeframe.

LikeLike

It was no such thing. The (British) Indian Army was not “Royal” any more than the current British Army is the “Royal British Army.”

FFS, stop inventing claims that are not supported by facts. Your theories are not based in reality.

LikeLike

http://www.britishmilitarybadges.co.uk/Products/royal-indian-army-service-corps-riasc-shoulder-title-1.html

LikeLike

Hi, I’m french author for Cibles Magazine, a review for antiques & moderne firearms. I currently write a real testing and historic presentation for the Lee Enfield N°5 Mk1. We have some models, in really goods conditions, available on our market. I write to promove this model for sport and playful purpose. I still had some information and documention, a friend of mine live in Australia. Are you agree to give me right for using some photos and informations from your web site? Naturally, I give any information to my sourcing.

Thanks a lot for your feed back, you can find the web site to the magazine below

Sincerely

Julien

http://www.crepin-leblond.fr/cibles/5464-revue-cibles.html

LikeLike

Yes that is fine, the photos are not all mine however.

LikeLike

Royal Hong Kong Police Use .

LikeLike

As an owner of 12, I really appreciate the article, the photos and the work that went into it all. Thanks so much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve seen a Indian Railways Government Railway Police (GRP) Constable armed with a No5 MkI standing guard at Bangalore Cantonment railway station in 2003.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A few other places they show up:

1) Indian UN peacekeeper forces that went into the Suez post November of 1956 had Jungle carbines. There are pictures of them watching the UK paratroopers withdraw.

2) Edzell in his book on military forces from 1988 lists Pakistan as having Jungle carbines still in use in 1987 as police weapons.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have a No 5 Carbine that was likely in the Asia theater post WW2. It has unit markings on the butt stock , does anyone know what unit the following would be:

26 10 48

I H L

74

A. Sqn

The date is basically the year of the start of the Malayan Emergency Force operations. Not sure if I H L is a unit, the 74 maybe a rack number or regiment. A Sqn is the sub unit.

This one has me stumped.

LikeLike

Hi

I have one marked

26.10.48

I.H.L

150

B.SQH

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have never heard of those, are they importers marks?

LikeLike

FFS, a badge-peddling website is not any sort of authoritative reference. The badge you are citing is for the Royal Indian Army SERVICE CORPS. The RIASC — like its British Army equivalent Royal Army Service Corps — was a very small component of their respective Armies. They provided transportation services, food, firefighting, maintained barracks and so forth. They were not even combat troops, let alone the entirety of the Army.

Quite simply, THERE WAS NO SUCH THING as the “Royal Indian Army.” Five minutes of actual research would make this obvious.

And the possessive form of “it” is “its,” not “it’s.”

LikeLike

Hi, im very interested in the use of The No 5 at Arnhem. I Have read different opinions About This. Heat is Your opinion and do you have any sources?

Many thanks.

LikeLike

I dont really have any specific info on how it performed there.

LikeLike

No 5 MK1 ROF(F)

10/44 B5***

I love this rifle and feel its worth more to me than what others say its worth. I have been able to hit targets accurately out to several hundred yards. Kicks like a mule !!! Anything anyone can add to the history of this particular rifle?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, I’m also very interested in the use of The No 5 at Arnhem with UK para. I Have read different opinions about this too. Do you have a source which shows that the British para or some elements of the force did indeed use the No 5 on the Arnhem operations. Was it a specific Regiment/battalion or company that used them? There were large enough quantities by this time, but I can’t find any reference they were approved for use (fielding). Thanks

LikeLike

I am not certain which specific units were issued it first, sorry.

LikeLike

Here’s an example captured in Afghanistan:

https://www.milsurps.com/showthread.php?t=55903&page=7

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great article. I didn’t realize the interesting life of this weapon that was never fully accepted by the British military. Despite the “minor” technical comments about the lineage of the weapons’ use post WW11, I was definitely enlightened about the impact that this weapon had during global conflicts.

In 1961 I bought a military surplus No. 5 Mark 1 Enfield thru the National Rifle Assoc. If memory serves me correctly, I spent less than $30 for it.

It was my intent to modify it for ‘sport’. I discarded the entire military stock and purchased a 2-piece walnut ‘sport’ stock from Herter’s (no longer in business). I removed several items from the rifle and then put it on the shelf when I started going out with girls. After 60 years and 4 household moves, I found most of the pieces and decided to continue with the refinishing. Unfortunately, a few of the critical pieces were lost (flash suppressor and safety lock), but I have since found replacements for them.

On the receiver and trigger guard there are paint remnants but after all these years I can’t determine what the actual color was. It appears to be something very close to the US Olive Drab. I will be painting all of the components (except the barrel) with the OD. If you like, I will be able to send a photo once everything is complete.

Jerry S.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Im looking for clarification on one thing. Were the ex-Malaysian No.5 Mk.Is bayonet lugs removed when they were put into Police service or when they transitioned into the civilian market from the Police Field Force?

LikeLike

I am not sure, sorry.

LikeLike

I have a No 5 MK1 ROF(F) that its stock is painted in black lacquer with a butt stock badge missing. I have not found any black stocks in my research but does not look restored or refinished.

LikeLike

I have never seen any like that. Was it possibly painted by a previous civilian owner?

LikeLike

I have a No 5 Mk 1, dated 9/44, Serial No P14 _ _. I bought it because at the time the allies invaded northern Burma, my dad had been a POW under the Japanese, slaving along the Burma/Thailand “Death Railway”. It comforts me to know this weapon may have been heading south toward his ultimate liberation. There are no unit markings on the weapon or stock, but it does include the characteristic thru bolt on the fore-grip, approximately 1″ forward of the receiver ring – indicative I heard of Indian Army service. Does anyone have insight into whether this weapon may have been used in that campaign? FYI, my dad started in Burma in 1942, along with too many others building that railroad. He was within a few miles of what became known as the Bridge over the River Kwai when he was liberated in Aug 1945 by the OSS. Though far removed from the allied Burma campaign at the time, he remembered Jap troops headed north up the railway. Later, he recalled they came back in defeat. Some were pulling cannons in the rain with ropes and with their tires so worn out they flopped on the rims, skidding in the mud. He said it was clear they had been given a rough time. MC

LikeLiked by 1 person

I dont believe any rifles were marked for specific campaigns or units. Does it have any postwar markings on it?

LikeLike

I had an Australian made .303 that had a cut down stock, and adjustable sights., so similar to the Jungle Carbine. I never found the recoil too savage. I took the pad off and could fire 80 rounds at the range, with out ill effects next day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Australian shoulders must be made tougher because I start whining with a 12 gauge. lol

LikeLike

The likely cause of “wandering zero” was the ferocious recoil of Mark VII .303 Ball ammunition in the shortened and lightened Jungle Carbine. The previous carbines were all known for their stout recoil.

In the Martini-Henry family, there was a reduced-power round designed for the carbines to allow cavalrymen to use their weapons without beating themselves to death in the process.

LikeLiked by 1 person